Liaisons is an international editorial collective that gathers experiences from struggles around the world. For our second book, Horizons, forthcoming from Autonomedia, we asked comrades what they thought about the prospect of revolutionary horizons today.1 With texts from France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Sudan, and the US, Horizons is a planetary attempt to rethink and renew the revolutionary tradition in the twenty-first century.

In the following excerpt, some inhabitants of Upstate New York write about their experiences moving from the city to the countryside. Examining traces of previous waves of communal experimentation in their area, they interrogate the relevance of utopian and countercultural traditions in an era of planetary upheaval and mass extinction. Advocating neither social perfection nor rural refuge, they present the rebirth of the commune as critical to today’s revolutionary horizon—an earthbound power capable of shattering the capitalist globe and ushering in new worlds.

Two Movements

Day breaks and the mountain is in motion. Those in the fields are already sweating. Those tending to the animals spread feed and prepare for milking. Some brew the morning coffee, others begin a long commute to those islands of economic development away from the mountain. Journey down the road and you’ll pass an older neighbor doing their part to remove algae from the pond. Hailing from the generation that tuned-in, turned-on and dropped-out, their story—a revolutionary withdrawal—is one of many which animate this place. Across the dirt road, stone walls worn by the century mark the remnant of a forgotten utopia. Near the pond, a single gravestone: “Shakers.” Here, surrounded by depopulated small towns and struggling small agriculture, we reside in a strange eden. Our story will be one of love affairs, toil, ritual, conflicts, and feasts built on the shared dreams of a new revolutionary era.

We stand in the Taconic Mountains, part of the ancient Appalachians stretching unbroken for thousands of miles, crossing borders, cultures, and histories. These mountains form a modest ridge, separating the Hudson Valley to our west from the Berkshires to our east. This terrain was once glacier, then forest traversed by the Mohicans (Taconic, from Taghkanic, meaning “woods”), then clear-cut farmland of European settlers. Today it is northern hardwood forest once more, returning amid patchwork farms and small towns. To live in these mountains is to be the beneficiaries of eons, of the immense movements of the continents, of glaciers, of rivers and springs, of fires wild and controlled, of centuries of cultivation, of generations who walked before.

We are beneficiaries not only of these natural and social phenomena, but of the multitudes concealed by the monolithic name America. Across this vast geography, there has never been a unitary order. Spirits traverse the land, animating it with radical incongruence. The spirits might tell one story: that this place has always been home to a peaceful, communal way of life. Or they might tell us the story of war between the Mohican and Mohawk, challenging the last vestige of Rousseauian illusions and revealing an ethical wedge that will always split the land. This continent has always been a tangled wellspring of exodus, ethical polarities, and turbulent communions. This was why Europe was compelled to release its grip and also why the Founding Fathers would construct race as a legal category, hoping to stave off the unruly spirits they found. America is the subject of a dissonance that lays bare the limits of every nation’s fictitious identity.

As we inherit the complicated legacy of this nation, so too do we inherit the legacies of social dissent embedded within the mountains we call home. We reside on this land in the shadow of two radical experiments, part of a tradition both adjacent to and distinct from the American lineage of revolutionary upheaval. The first emerged alongside the turbulent history of the early United States, while the second erupted amidst the transformations of the postwar era. Each were profound experiences of collective rebellion at the level of daily life.

The Shakers—religious separatists preaching equality of the sexes and abolitionism—sought perfection amid a Millennium they believed had already dawned. Living on a former Shaker settlement, their material legacy—fields and forests, stone walls and sturdy buildings—make up our everyday environment. Inhabiting their traces prompts us to consider their beliefs and collective practices, challenging us to imagine a movement which lasts beyond our own lifetimes.

The back-to-the-land movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s represented a vast countercultural secession from modern society, aiming to peacefully transform “consciousness” and, through doing so, the world itself. Its presence manifests in the disposition of many locals—neighbors, friends, elders—who participated in that experimental exodus and whose experiences brought them to this mountainside. Carrying with them skills, stories, and values of that era, they have helped us form a living, tangible link with a prior movement of tremendous scale and creativity.

From a historical perspective, these two movements are exemplary of the irrepressible communal impulse traversing America, a seed of communism at home on this continent as much as anywhere else. The Shakers are the country’s most enduring communitarian society, a 250-year-old religious order which developed both within and apart from the American project. The back-to-the-land movement was America’s biggest communal wave, totaling some one million youth who joined the communes in a single decade. Together, they amount to two of the longest-lived and the largest experiments in the history of American revolt, collective attempts to break from the dominant society and construct a new art of living.

The path we follow takes us through these movements. Without understanding their insights and missteps, it would be difficult to confront the unprecedented demands of the present, the necessity to seize the means of existence. While we seek to make a break, to cast off the dead weight of the past, we must also face the history written into the territory we inhabit. These austere millenarians and wild freaks are missing from the pages of official revolutionary history, but in their desire to remake the world they find their place among our forebears. If we do not raise the expected criticisms, this is because we want to recover another image of these movements, one lost under the standard narratives.

Both of these collective experiments partook of an optimism which is unimaginable now. Utopian enthusiasm suffused the Republic during the Shaker’s heyday, a widespread faith in social progress only later snuffed out by the Civil War. The back-to-the-land movement lived on the verge of imminent global transformation, at least until the upsurge of the revolutionary sixties crashed into the reaction of the seventies. A future brighter than the past, a core belief animating each prior movement, is a hope unceremoniously put to rest by our troubled era. Today every vision of the future rings hollow which does not include its dystopian truth. The violence of capital is written into geologic strata, the atmosphere, and our psyches. At the threshold of economic expansion and technological acceleration, the earth quakes. With every storm and rising tide, the climate asserts its reign. Here lies a radical schism and the questions our time imposes. Whatever legacies these two movements have left us will have to be rethought in the blinding light of the epoch.

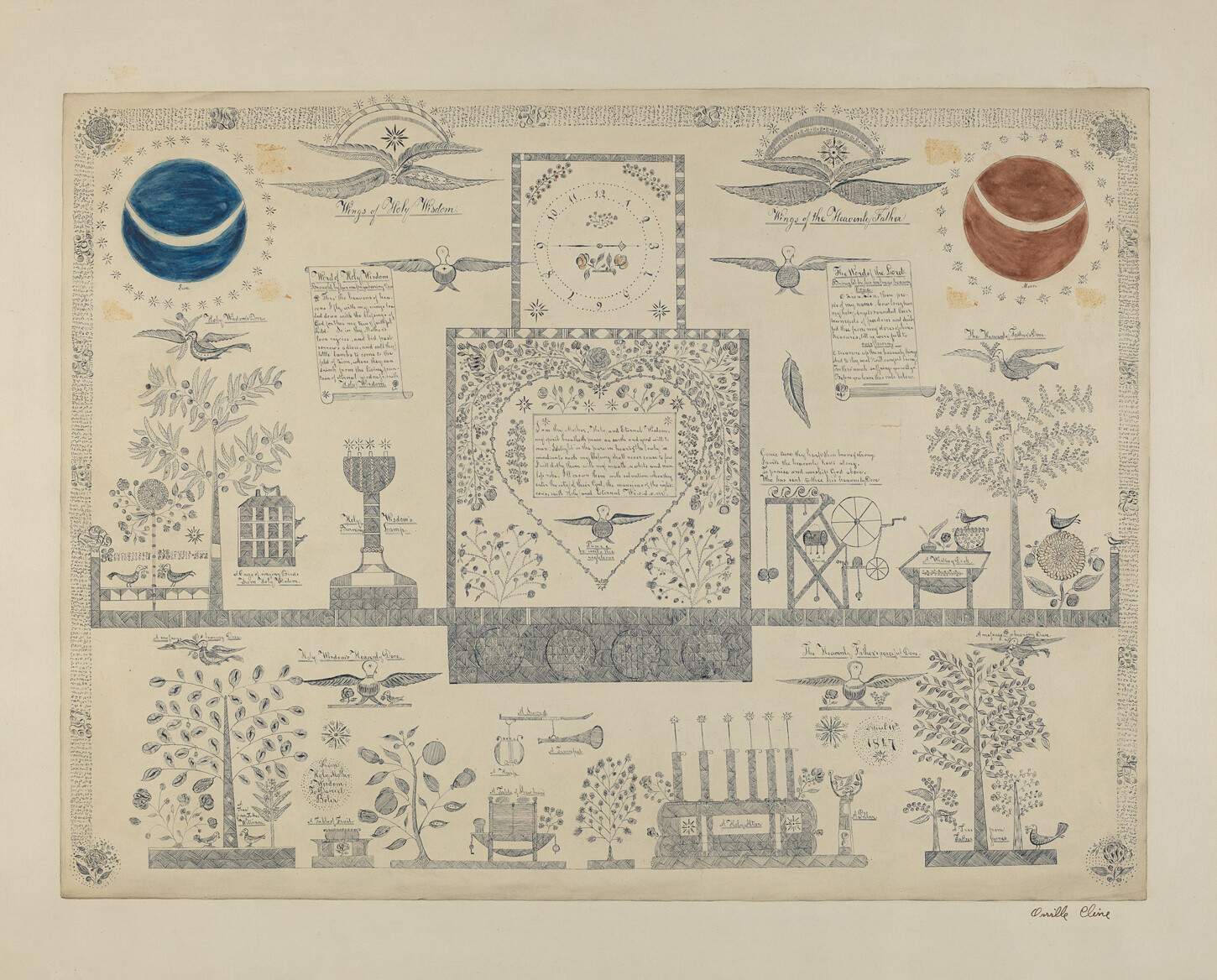

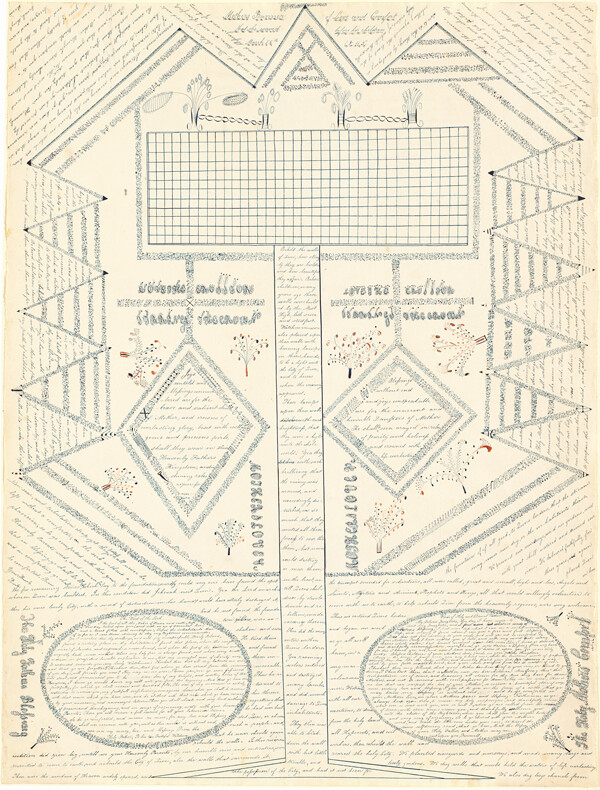

Rebecca Landon, Mother’s Banner of Love and Comfort, 1845. Accession number: 1971.83.29. In the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Public domain.

Life in Common

There have always been dissident communities on the fringes of the American nation, those who rejected the vaunted “liberty” of the individual and instead sought freedom through life with others. From the famous utopian communities of the mid-nineteenth century to the counterculture of the mid-twentieth, we find again and again the powerful refrain of common land, common labor, and common bonds.

Emblematic of the religious exodus from Europe, the Shakers were a near-heretical sect led by the charismatic Mother Ann Lee. In the relative isolation of the American countryside, they enacted their communitarian beliefs: holding property in common, practicing cooperative agriculture, and living in collective arrangements of non-biological “families.” At their peak in the 1840s, the Shakers had forged a network of eighteen prosperous communities, ranging from Maine to Kentucky, with around six thousand total members. Their successes even caught the eye of Friedrich Engels, who praised the Shakers’ social arrangement in a survey of existing “communist colonies.”2 Communism, after all, was a Biblical mandate, as Shaker theologians pointed out. According to Acts, the first Christians “had all things common.” Over decades and then centuries, the celibate Shakers developed forms of work, worship, and living in which the communal principle prevailed—sometimes at the expense of individuality. While the Shakers held themselves apart from politics, their spiritual commitment to egalitarianism led their communities to plant extra crops for the hungry to take from their fields and even to help former slaves escape to freedom as part of the Underground Railroad.

Like the communal wave which swept America a century before, the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s was a widespread, sudden phenomena. Against a backdrop of student unrest, war in Vietnam, “race riots,” and the atomic bomb, disaffected youth rejected mainstream society and instead sought the liberation of an “authentic” self. The communal element of the counterculture largely had its origin in cities—with loose networks of crashpads and free stores—before the back-to-the-land communes took off. In this mass disaffiliation, upwards of one million “free spirits” headed to the countryside. They founded thousands of communes, spreading across the Pacific Northwest, the Southwest, New England, and everywhere in between. Fleeing their middle-class upbringings, young communards adopted an ad hoc communalism, sharing land and houses, work and tools, clothes and drugs, languages and desires. At the movement’s creative height, there was a vast, cross-continental network, composed of dropouts and draft resisters, artists and spiritual seekers, runaway teens and fugitives in the revolutionary underground. Unfortunately, the serial failure of many of these vibrant, if short-lived, communities has painted the word “commune” with an often negative connotation.

What speaks to us about these movements is their ardent desire to put life in common—and the fact that they organized themselves to make it real. But it troubles us that both of these movements and the way of life they practiced were premised upon their ability to set themselves apart from the wider world. One of the central religious tenets of Shakerism, after all, was “separation from the world,” realized through physical isolation of their villages and strict rules governing interactions with outsiders. Back-to-the-land communes also sought a degree of geographic remove, communards trying to put as much distance as possible between themselves and “the system.” Today, as capitalism has encapsulated the entire planet, we know there is no privileged site of separation to which we could flee in order to insulate ourselves from its designs. Simply moving to the countryside will not free us from the coercive forces to which we are exposed. The economy is everywhere. As are the apparatuses—technological, juridical—that manage it.

The conditions for carrying out a separation have been historically and technologically outmoded. There is no opening for an alternative outside the system, from which these prior movements premised their communal experiments. As it stands, what our lives have most in common is a kind of collective dependence on the systems we seek to overcome and the isolation they impose on us everyday. We have no choice but to live communism in the midst of everything: whether we are in cities or countrysides, no matter how much we currently rely on structures we despise, no matter how entangled we are with systems we reject. A revolutionary force will be built by immersing ourselves in the world, not separating ourselves from it.

However flawed they may have been, the fact remains that these two movements remind us of the communal undercurrent which flows through these lands and through this very mountain. Their histories reflect other histories unfolding concurrently, of workers’ refusal, native resistance, and cultural exodus. Fragments of America were once held in common and they may be so again. Our starting points may be different from the old utopian and communal movements, but the necessary gestures remain the same. What made a life in common possible was the desire to live it and the decisions carried out to realize it. The viability of these prior forms of commons wasn’t in their rural remove, but in the means shared, the techniques developed and deployed, the spirit that enlivened the land as common territory. Commons are both place and practice. They are sites and acts of contestation where the dominant order is decomposed, giving way to something new.

The commune flashes in and out of American history, a signal flare that life could be otherwise. In the twenty-first century we don’t have the luxury of utopian moralism nor the modern communes’ fantasy of escape. We are confronted with two visions of the future: one, the miserable promise of the end we already endure, the other, an interminable course where life breaches all fatalistic certainties. Either capitalism ends or we do. Living communism is a serious task. Faced with an apocalyptic horizon, we must break with a form of happiness equivalent to numbness—the contented oblivion of our time. Our happiness rests on our ability to mourn what we’ve lost, to defend what we love, and to live more free than the nihilists at the helm.

On our mountainside, where daily life can feel frustratingly small at times, we are beginning to ask ourselves these questions and to organize ourselves accordingly. How do we put our lives in common, with an entire world stacked against us? How can we build a shared life, without cannibalizing each other in the process? It is one thing to live together, to make collective decisions, to share the burden of work intrinsic to rural life—from firewood to childcare. It is another to build a commune that exceeds this mountain and open land and resources to collective use. To network between a new wave of communes is the only path we see towards a future where our experiments overcome an insularity which would be the same as slow defeat. A future which demands we rediscover how to live, as the very ground we stand on shifts and so much we take for granted falls away.

Self-Sufficiency

As a settler-colonial nation with fantasies of taming “the wilderness,” the American imaginary has long been fascinated with self-sufficiency. This tradition passes from the early frontier to the Transcendentalists, through the generation of the Great Depression—for whom keeping a kitchen garden, canning, and raising animals were means of survival—and finally down to the modern communes and today’s homesteads.

The early Shakers were remarkably self-sufficient in terms of material needs. They pursued an independence in matters of “temporal economy” as their religious separatism demanded. Famously inventive, the Shakers supplemented extensive agriculture with handicraft production, making everything from their own buildings and furniture to their tools and clothes. But in later years they turned more towards commodity production, relying less on subsistence and handicraft than by selling their goods to “the world’s people” to raise needed revenue. In a sense, the Shakers’ hard-won independence was eventually undercut by their own commercial success. Their iconic boxes, brooms, and chairs—as well as seeds and medicinal herbs, their use based on Mohican knowledge—brought considerable profits as well as more extensive contact with American society. As the twentieth century approached, many turned away from the rigors of Shaker life, while dwindling communities scaled back their practical activities and became more specialized in what they produced.

While the back-to-the-land movement preached global interconnectedness, their everyday activity bent towards self-sufficiency. Among the first to grasp the catastrophic ecological implications of “the system,” they sought to create viable alternatives to a mainstream they saw headed for collapse. The communes’ response to industrial capitalism was to produce everything they needed directly from the land and by their own hands. Organic farming—which the movement helped popularize—was widespread on communes. Inspired by the ubiquitous Whole Earth Catalog, many communities adopted “alternative technologies” like solar energy to further reduce their dependencies and live more in keeping with the newly discovered “limits” of the biosphere. Yet a constant feature of accounts of the movement is a lack of appropriate skills, the hardships of winter, poor nutrition and frequent illness, and young communards being generally unprepared for the sheer difficulties of rural life. Almost without exception, communes fell short in their quest to truly meet their own needs. Beyond interpersonal strife, material obstacles figure heavily in the failures of communes and contributed to the rapid decline of the movement, with enthusiasm for the idea of self-sufficiency succumbing to the difficulties of achieving it.

Each movement’s passionate drive towards self-sufficiency, however morally pure or materially well-organized, always seemed to crash against a still deeper reliance on the economy. The lesson of these uneven experiences is not that the effort proved not to be worth it. We see it more as a measure of the difficulties before us and a call to rethink how we conceive the task to begin with. The Shakers and the back-to-the-land movement both grasped the essential logic of self-sufficiency—the power that comes from providing for ourselves, outside of a demoralizing system. Their failure was not tying their pursuits to the overcoming of that system.

For us, the concept of autonomy, as opposed to self-sufficiency, is a more useful framework. Autonomy is less the moral imperative to provide for all of our needs than the strategic severing of certain dependencies we have on the structures that govern us. Rather than trying to do everything ourselves, building autonomy requires assessing which dependencies, if fulfilled within our collectivities, would grant us the most freedom. Reducing our dependencies on decisions made elsewhere increases our interdependencies through creating bonds of material skills and mutual affinities. Autonomy repositions our gaze away from an economy that holds us hostage and centers agency on our collective capacities. In this gesture, every question of “how” becomes a negotiation of our strategy.

In the twenty-first century, we live under the global reign of an economy synonymous with catastrophe, a planetary system that undermines the very conditions for any form of life to continue. The isolated ability to provide a good life for a limited few is not a viable course but a form of resignation. Whatever idyll experienced, whatever refuge carved out, will be confronted by a radically altered world along with the hardships it brings and the social pressures it unleashes. The cruel whims of an unpredictable climate may cancel out everything people may have achieved in chain reactions originating continents away. The American tradition of self-sufficiency is too narrow in scope, too premised upon locating a stable outside no longer there. To pursue self-sufficiency in our era appears to us significant only insofar as it augments the collective capacity to undo the blackmail of capitalism. We can no longer seek to become self-sufficient for our own sake, for the amelioration of our own lives, but to build the autonomous capacities that could end, once and for all, the impoverishment and destruction called economy.

How we meet our needs is always a political question, a vector along which power travels. We already feel the tremors. We watch as forests disappear in flames or megaprojects, the air turns deadly, and waters turn to poison. Pipelines criss-cross our region. A nuclear plant sits just south of us along the Hudson River, not far from a faultline. Given the stress already placed on critical infrastructures, reducing our systemic dependencies becomes even more urgent and necessary. The epochal question is both simple and complex: how to live in a dying world? The ruling class is already predicting food shortages, resource wars, and vast uninhabitable zones. While most of the world will contend with how to keep living, they plot how to keep ruling. To learn how to provide for ourselves is the challenge before everyone—as is how to turn that capacity against those who seek to rule us. Reappropriating our collective capacities of reproduction will be a matter of resistance as much as survival.

Living here now—on the same lands where these movements tried to fashion a collective existence—has helped us understand the necessity of building autonomy and the political horizon that gives it meaning. More importantly, being here has given us time and space to materially experiment with meeting our own needs—to discover how food tastes better pulled from the dirt and how to rejoice in laboring together. We know very well that to grow a portion of our food, to preserve it, to raise animals, to make herbal medicines, to fell trees and split the wood which heats our homes through cold winters, is arduous, unglamorous work. But the increased responsibility we have over our own reproduction—and especially the skills we’ve learned along the way—has been meaningful for us, in spite of its inadequacy.

If anything, these tentative steps have given us the first glimpse of the daunting scope of the material challenges ahead. We know we don’t have the answers. But what we can say for certain: food, water, shelter, energy, care—each is a realm in which we will have to be organized on a massive scale, beyond any one group and beyond any one place. We will all have to ask what systems we must free ourselves from in order to live. What infrastructure we need now and what we can predict we might need in an uncertain future.

Are there problems we can solve here that might be useful to others elsewhere? Which of our material practices could be expanded, weaponized as part of wider struggles? How can communes interlink, form alliances, and share skills and resources at the necessary scale and speed? Amid deepening systems of control and cascading failures of infrastructure, can we help proliferate the ethics, tools, and techniques necessary to lead dignified lives? How can we learn again to live on the earth, as it is forever altered by systems which seem to lead inexorably to extinction?

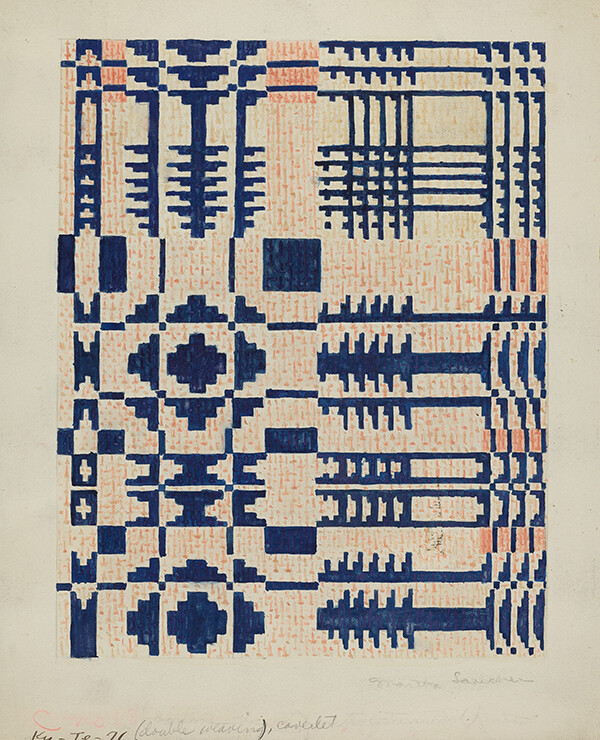

Martha Sancher, Shaker Coverlet, 1935/1942. Watercolor and graphite on paper. Index of American Design. Accession Number: 1943.8.13670. Public domain.

Earthbound

The Protestant exodus from the Old World was animated by the search for “a new heaven and a new earth,” as Revelation puts it, a quest for the Millennium many thought would be inaugurated in the newly discovered Americas. But Christian settlers didn’t so much encounter the promised apocalypse as bring it with them. If modernity began with the cataclysmic violence of earthly conquest and colonization, then perhaps it’s fitting that it ends with the earth breaking back into history, bearing its own apocalypse.

Whatever the findings of modern astronomy, the Shakers believed that heaven still ruled over the earth, that man’s destiny lay beyond this fallen world. “This earth was created for a temporary use,” as one Shaker theologian explained their cosmology, “and was never intended to be the abiding place of man.”3 But even if their time here was to be short-lived, Shakers couldn’t simply neglect the lands which nourished them. While their hearts may have been drawn upwards to God, their hands learned to work the earth. Abundant produce and herb gardens, bountiful orchards, and avid beekeeping testified to their practical acumen and even their delight in matters of the natural world. Living on these same hillsides decades after the last Shakers departed their village, however, raises complicated questions. Believing themselves stewards of creation didn’t prevent Shakers from draining swamps or clear-cutting forests to establish pasture and extract resources. Their earthly legacy is a mixed one, posing to us in concrete fashion the question of how we live upon the land and how we will leave it for future generations.

The back-to-the-land communes were among the first popular manifestations of the nascent environmental movement, just beginning to warn of the dangers of plastic, pollution, and industrialization at a global scale. Borrowing the language of cybernetics, communards spoke of a “whole earth”—the unity of our blue planet, interwoven, at equilibrium—just as the immense threats to that wholeness were becoming clear. The era-defining first images of earth as seen from space—released after a campaign originating within the counterculture—were akin to cosmic epiphany for many communards. It was a near-mystical realization of the interconnection between all things and proof of life’s delicate balance, even of the existence of Gaia. “We are the first of the planetary people,” wrote one inspired communard at the time.4 Communes across the country aspired to become catalysts of this burgeoning “global consciousness,” experiments in the shared desire to live with the land rather than against it. As this moment profoundly shaped our conception of the planet and helped diffuse ecological principles throughout society, today we still carry an image of the earth as envisioned by the communes.

Each movement had to grapple with the question of the earth: how to live upon it, how to care for it, how to relate to it, how to understand its ultimate significance. The Shakers, as we know, subordinated life on earth to an eternal spiritual existence, trusting in the comforting guarantees of the divine. The back-to-the-land movement, on the other hand, grasped the extent to which life was dangerously earthly, our existence precarious insofar as modern technology endangered the entire planet. On this point we can say they were right: life will be earthly or not at all. That the earth and capitalism are incompatible—a key insight intuited by the movement—is even more undeniable today given the specter of climate change. While the communes feared the final catastrophe would be set in motion by nuclear warfare, now we anticipate an end which doesn’t even need a detonation. It is simply the everyday continuation of capitalism that will suffice to bring about the apocalypse.

Yet even in their affirmations of the earth, their conceptions of it have proved false. The Shakers espoused the familiar Christian belief that the earth was man’s dominion, that we were lord and master of creation. By now, we have seen what man’s mastery entails: a creation drowning in plastic. Man—not the God of Revelation—is the agent of calamity responsible for mass extinction. Like the wider field of ecology at the time, the back-to-the-land movement mistakenly envisioned a naturally harmonious, balanced world. The communes did see man as the culprit behind environmental disturbances, but their belief that the earth might be somehow restored to its intended state has now been put to rest. Instead we are entering a period of planetary conditions unprecedented in terms of human habitation. The arts of existence collectively developed over thousands of years will be thoroughly upended, given that the climatic patterns which underlay their wisdom can no longer be taken for granted. It may turn out that “Western civilization” was only a myth of the Holocene.

The paradox in which we are caught is as follows. Modern science, with its unchallenged claims into the nature of reality, has rendered the old cosmologies inaccessible to us. There is no meaning-giving beyond, no vault of heaven, no promise of salvation such as the Shakers experienced. Nor is the seventies fantasy of a benevolent, wise Gaia a credible metaphysical recourse. Situated on the brink of catastrophe, it may only be in the exit from the modern age that we might rediscover the meaning of the earth. The cosmological significance of the earth is not just its position relative to the universe, but our position with respect to it. Our lives and our fates are bound to this planet, our only home, in a bond that modernity sought to break at the peril of its own demise. To deny this link is to welcome the abyss, of escapism into space or into screens, into a closed-off human interior mirrored by a science for which nothing is real unless it can be measured, to invite nothing but cosmic indifference and the threatening solitude of extinction.

We must now ask what it means to be human in a world that is dying, at the very moment we realized the earth was vital. How to dwell in a world where we are not alone but entangled with all beings who comprise the vibrant plane of existence. How to live on lands that we cannot “return” to so much as recognize as already inhabited by countless histories and forces beyond ourselves. We know that no self can be sufficient unto itself—we live only in relation to others. Any real pursuit of autonomy begins with recognition of this deeper heteronomy: our dependence on those around us and those who came before, all the nonhuman forms of life in the great pantheon of being, the plants who breathe life into the world and the sun which animates them. We are not as gods. We are of the same matter and singular life which compose the flora and fauna layered across the earth. This is what we have in common and this is why we yearn for communism.

To move to these mountains was not an answer but the opening of a question, one that history has posed to the living with the clarity of destiny. What does it mean to live in our epoch, as we walk the thin line between revolution and catastrophe? In our fledgling attempts to live closer to the earth, the stakes of our time have become more clear, the challenges more defined. In the city, the apocalypse can feel like a foregone conclusion. In the countryside—surrounded by the profusion of life, bodies more attuned to the rhythm of the seasons—the end of the world is harder to believe in, but all the more painful.

How can we overcome the spiritual brokenness of our time, the planetary nihilism we inherit? How can we be rooted in a place, when everywhere is without foundation? To know the history of the land and the names of plants, to keep bees and to plant trees, to forage, to involve ourselves in the fate of the woods and the waters, to learn the constellations—all this might seem anachronistic or absurd. But to close ourselves off from the question of the earth, to deny our inseparable ties to it, can only mean extending the wake of destruction left by the preceding centuries. What’s needed more than ever is an affirmation of what’s vital. The belief in a terrestrial horizon, however fragmentary the terra has become.

Exodus

In spite of its individualist mythology, the desire for life in common burdens American history as a refrain of desertion, refusal, and rebellion. These communal forms of the past set the precedent for the revolutionary ethic of our time. What does it mean to stand on the same ground, hold ourselves to the same truths, when all possible horizons of our forebears have melted away like ice from the sea? Our time affords no utopias, neither the Kingdom of Heaven realized by life rightly led, nor the planetary wholeness dreamt of beyond the crest of progress. The communal urge, the subterranean rhythm of this great continent, can no longer be imagined as an end in itself.

This mountain, its springs and soils, gives rise to its own way of life. We start from here, our point of departure: the earth from which the mountain will feed a vast network of partisans, the animals which will pass on their wisdom to teach us to move freely, stalk prey, and avoid detection. The waters which will heal our wounds and nurture our young in a world at war with our bodies. Where we will sit with friends in late summer, gazing over fields of goldenrod, and swear to never let them take this from us. Where we begin to betray the sick vision of America inherited from our ancestors.

Exodus was the historical movement which remade America and which will come to undo it. From its origins, exodus has always meant a collective movement towards freedom. To depart, but in doing so create the conditions for others to follow. As the last revolutionary gesture permitted by our times, we embark upon this path with the knowledge that we do not depart alone. We stand in one location, on one mountainside, but exodus must unfold everywhere. From each of our histories, from each of our territories, an exodus must be carried out coterminous with revolution.

The task of our era is to reunite the form of the commune with its revolutionary potential. A potential the Shakers never sought, despite their radical egalitarianism, and which the back-to-the-land movement turned away from in their break with the revolutionary movements of their era. In our time, communes are already erupting across the world, each according to their own histories and struggles, bound to the earth and to their own articulation of life in common. Through the circulation of vibrant encounters, sympathetic affinities, and material linkages, exodus coalesces from a thousand points, oriented towards a common horizon. We set our sights on a terrestrial horizon, not only because we are bound to this earth, but because revolution in the twenty-first century must be planetary in scope.

To grapple with land and its histories is to rediscover life as a weapon. Only a weapon so total is powerful enough to combat the combined spiritual and ecological devastation of our time. We must learn to wield it with urgency. Let our expanding networks of communards, elders and children alike, nourish and shelter one another against those who would deny us a future, who claim that this is the end. Let our subsistence dictate the battlegrounds, where our familiarity with the land will give us the upper hand against those who wish to remove it from our power. Let our deepening connections with this earth, which grants us the means and willingness to fight, remind us daily what the stakes are—not only the worlds we build together, but the conditions for any world to come.

Friedrich Engels, “Description of Recently Founded Communist Colonies Still in Existence” (1845). Based on travel accounts he read, Engels lauded the Shakers not only for their material abundance but the fact that their communities had no police, no prisons, and no judges.

A Summary View of the Millennial Church, or United Society of Believers, Commonly Called Shakers, 2nd ed. (1848). Originally published by the Shakers in 1823, this book was among the first to systematically outline their beliefs, aiming to dispel the scandal surrounding some of their practices.

Ed Rosenfeld, “Planetary People,” in The Last Supplement to the Whole Earth Catalog (1971). Typical of the countercultural foment, this short essay combines systems theory with gestalt psychology, psychedelic drugs with Sufism.

Category

Subject

Excerpted from Liaisons, Horizons (Autonomedia, 2022).