Part 2: Shouts, Moans, Musics

Even though the captive flesh/body has been “liberated,” and no one need pretend that even the quotation marks do not matter, dominant symbolic activity, the ruling episteme that releases the dynamics of naming and valuation, remains grounded in the originating metaphors of captivity and mutilation so that it is as if neither time nor history, nor historiography and its topics, shows movement, as the human subject is “murdered” over and over again by the passions of a bloodless and anonymous archaism, showing itself in endless disguise.

—Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book”1

5.

From the vantage of more than forty years since Camera Lucida’s publication, of what use is Barthes’s punctum given the studium these days? The punctum, as the first part of this essay shows, serves Barthes’s willfully ahistorical appropriation of photographs to expressly private ends driven by the vagaries of affect and the penetrating force of grief. This will, this possessive grief, leads him to a profoundly asocial stance on photography writ large. Moreover, his despairing solipsism is premised upon a deeply racialized, gendered, and classed form of white normativity operating throughout the seams of his theory.

Given the belated emergence of the second, temporally inflected conception of the punctum in the book, and given its intensifying orbit around the maternal figure in Barthes’s Winter Garden Photograph, perhaps the critical question to ask of Camera Lucida needs to shift. Maybe the question is less “why withhold The Winter Garden Photograph?” or “what does The Winter Garden Photograph mean?” than it is: How does its retention instruct us as to the perils of Barthes’s method in this moment of acute, global violence mobilized in the preservation and legitimation of white supremacy?

Could Barthes’s punctum ward off the insurgent irruption of that Real which is buttressed by normative forms of racial, gendered, and classed violence within his text? Could it be that in disavowing any critical engagement with material social history, in working ahistorically from sentiment and affect, Barthes can attempt to uncouple his poetic production of meaning from any recognition of the differently subjected matter upon which it depends? To what extent are Barthes’s hierarchical and expropriative elucidations of the punctum not exemplary of a white “ruling episteme,” and of its “dynamics of naming and valuation … grounded in the originating metaphors of captivity,” as Spillers writes?

Camera Lucida begins its treatment of photography in intensely material, corporeal terms. In his search for the specific ontology of the photograph, Barthes finds that “the Photograph always leads the corpus I need back to the body I see,” implying an explicitly physical relationship between Photography (as corpus) and the Photograph (as the body I see).2 His theorization of photography is riven through with corporeity. The photograph “points a finger,” and

always carries its referent with itself, both affected by the same amorous or funereal immobility, at the very heart of the moving world: they are glued together, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures … as though united in eternal coitus. (5–6, emphasis mine)

Given this corporeal figuration of both the photograph and photography, Barthes’s dismissal of those studium photographs that “shout” (41), and of those studium images “surrounded by a noise” which will make meaning “less acute” (36) seems not only strange, but conceptually contradictory and arbitrary. So too his unilateral declaration that

the photograph must be silent (there are blustering photographs, and I don’t like them): this is not a question of discretion, but of music. Absolute subjectivity is achieved only in a state, an effort, of silence (shutting your eyes is to make the image speak in silence). The photograph touches me if I withdraw it from its usual blah-blah. (53–55)

As Barthes elaborates on the punctum, he declares that “the photograph can ‘shout,’ not wound.” Since photographs possessed of a punctum are those of a higher value, this establishes a rigid hierarchy not only of value, and of attention and interest, but most crucially of meaning for photography as a whole. Barthes’s rejection of the very corporeity he ascribes to photography legitimates a mode of attention that valorizes an absence of disturbance in favor of an abundance of propriety, an absence of noise in favor of an abundance of discretion. His schema privileges those photographs that, in their silence, in their “withdrawal from their usual blah-blah,” touch him in his efforts to attain an “absolute[ist?] subjectivity.”

In this contradictory rejection we find Barthes’s ocular-centrism, his reification of a mode of disembodied looking that seeks to “neutralize the phonic substance of the photograph,” as Fred Moten has written, and that proceeds from some notional point outside of materiality (and thus of history) and “exterior to the field of vision,” as Kaja Silverman critiques.3 What might happen were we to not only forsake this method and to reject its premise, but to instead look—and to listen—precisely where Barthes himself refuses to? Plainly, despite his prescriptive insistence that the photograph not shout, and despite his multiple gestures of aversion in relation to those images that do, the photograph itself will not keep quiet.

Tina Campt’s practice gives exemplary proof of what might be gained in inverting Barthes’s hierarchical model of punctum and studium, and in refusing his ocular-centric approach by beginning not only to look, but to listen—by moving from and through the historicity of matter. In her essay “The Lyric of the Archive,” Campt engages an archive of studio portrait photographs depicting diasporic black British citizens. These portraits, produced by Ernest Dyche Sr. in Birmingham, England in the 1950s, were rescued from imminent demolition in 1990. Campt recounts her participation in the assessment of this archive, as she “gathered box after box of images and brought them upstairs to the office.”4 She writes that

from the moment I first laid eyes on them, I have struggled to understand what exactly these images were saying, and what it was they told us about photography and the making of community in diaspora. But I also came to realize that what was so captivating about them is not only what I was seeing, but what I was hearing as I looked at them—a playful yet insistent hum that I found difficult and, frankly, a mistake to ignore.5

In response to this insistent aural sensation, Campt sets out to “think the constitutive supplementarity of the visual and the sonic as a larger whole.”6 She attends not only to the materiality of the objects but to that referent which adheres to them, and that constitutes the corpus and the body (the archive and the photograph) to which she will respond. This form of response understands and embraces the fact that looking at and listening to photographs constitutes “a synesthetic encounter that, I would contend, certain photographs involuntarily require.”7 In stark contrast to Barthes, Campt argues that images’ effects and intelligibility emerge from a wider synaesthetic field, and thus the “complex musics of the photograph are … a sound that is not contained within the image, but one that precedes the image as its constitutive and enunciating force.”8 Thus, sound is a constitutive element in these photographs’ production of meaning, in their capacity to utter and articulate themselves. To reject noise, to reject materiality is thus to reject or disavow meaning. She writes:

I would like to suggest that thinking about images through music deepens our understanding of the affective registers of family photography and helps us understand how such images are mobilized by black families as a practice that articulates linkage, relation, and distinction in diaspora.9

Campt’s critical approach values the role of affect in photography’s generation of meaning, but as a vital element in a social and diasporic practice. Barthes’s resolution to make “what Nietzsche called ‘the ego’s ancient sovereignty’ into a heuristic principle” (8) stands in diametric opposition to Campt’s investment in the sociohistorical basis of photographic meaning, since black social practices that extend over time are premised on shared rather than solipsistic feeling. She decides to treat the Dyche photographs as an archive, in series, and to “read the images like music,” remaining attentive to the patterns of their soundings, to their specificity within their homogenous and generic context. Such a mode of reading “means using musical structure as a heuristic lens through which to engage the photographic practices of black communities in diaspora, and as a framework through which the photograph registers meaning.”10 Campt’s rigorous attention to these studio portraits requires that she embrace their generic form. By emphasizing their serial nature—over and above the individuated aesthetic distinctions of one or another image—she valorizes the studium as against the punctum, and departs from the hierarchical model Barthes outlines.

She notes that Dyche’s “extremely formulaic images,” which are “staged,” “predictable,” and “posed,” “show smartly dressed individuals—black folks putting their best foot forward.”11 While they are littered with odd anachronistic details (“the wilted chrysanthemums on the table,” or “an unlit cigarette held demonstratively”), Campt argues that “Such ‘points’ and details are a function of the formulaic nature of their photographic genre. They do not rise to the level of punctum; rather, they dissolve again into the background.” According to the phenomenological model outlined by Barthes, Campt writes, “the attributes I find so compelling relegate the repetition of these details of form and genre instead to the less interesting category of studium, rather than constituting the more invigorating forms of punctum prized by so many theorists of visual culture.”12

But having determined to set aside that hierarchy, and “take studium seriously and not dismiss it so quickly,” Campt demonstrates that a “reconceptualization and revaluation” of “the seriality of studio portraiture” can enable a substantive recognition of “the image-making practices of black diasporic communities in particular, as a significant and revealing form of expressive cultural practice.”13 She thus assesses the archive as a collective utterance, and not a loose concatenation of individual images interpretable on the basis of their singular aesthetic or circumstantial distinctions. The repetitions of furniture that populate the frames, the subtle alternations of flower vases, the recurrence of pose—these generic features are read in a generative rhythm of transnational communication that at once recapitulates and alters its own codes. The photographs constitute complex sites for performative action occurring in the present of their making, as subjects acquire the distinction in image that they materially seek in life, and again in their reception, as family members and friends receive a record of that instant as a remnant of ongoing actions in worlds far removed. They are also rehearsals of an ongoing refusal to conform to whatever racist trope of the black or Asian immigrant that imperial Britain might otherwise seek out, in order to fix these people “in their proper place.”

The subtle inflections and modulations in the normative codes of an immigrant subculture, the small conventional acts of enunciation that mark “the extension of a field” (25) turn out to be the lifeblood of diasporic bonds that are always under pressure from the strictures of white supremacy. These bonds make matter, they hum, they shout, they repeat and reverberate among peoples and across time. In our attention to Campt’s serial portraits, and their fashioning of specificity and generality, of individuality and collectivity, we are imbricated in the “ongoing production of a performance” in which the relationship of the individual to the collective is reconfigured through the portrait photograph.14 We are subsumed within the series into an ensemble comprised of a difference that does not insist on radical or violent differentiation.

In both Campt’s and Fred Moten’s theorization of sound and music, they develop notions of an ongoing performance—the contours of a subtle and perceptible grammar through which a social practice happens or matters. In Campt’s work, an archive of family photographs constitutes a record of choices and intentions which can be attended to via the recursive rhythms of multiple black bodies entering a photographic studio to produce—serially, in subtly variegated extension—a record of aspirations toward a futurity not stably attainable in their immigrant present. In this sense, each print, each face, each pose strikes a note, accumulates into a rhythm, generates a discernibly choral hum.

Within Campt’s model, ostensibly aberrant images that veer far from the conservative mean of Dyche’s family photographs—pictures that evince, for example, a “proud and voluptuous sexuality” in the bikini-clad figure of a smiling black woman—give voice to “a suppressed melody of licentiousness.” This shifts into something harmonically “in time” with the “ensemble performance” when read through the prism of Caribbean culture’s celebration of “sexuality and sexual potency … for women.”15 When read within the lineaments of black social practice, that which seems disjunct as a punctual aberration proves to be “playing off tempo, but in time.”16

In keeping with such sublations and articulations of difference within the choral whole, Moten writes:

Mingus thinks that in the absence of a law of movement to break, calypso falls into the random constraint of a death spiral. However, Dudley shows how the maintenance of the circle’s integrity requires the legal procedure of an articulated ensemble, what Olly Wilson calls a “fixed rhythmic group” whose “rhythmic feel is not produced by a single pattern … but is a composite generated by several instruments that play repeated interlocking parts.” No hegemonic single pattern means no sole instrument or player responsible for that pattern’s upkeep. There is, rather, a shared responsibility that makes possible the shared possibilities of irresponsibility.17

Within the shared sociohistorical field of black cultural practice, within the neglected realms of the studium, homogeneity and heterogeneity are instead bound up in shifting but complementary relation. In this model, repetition and differentiation are not antagonistically opposed. Difference is not exclusionary, and similitude is not unprepossessing. As Campt shows of the image, and Moten here shows of music, these are black social practices in which “me” blends into “we,” rather than “I” standing apart from “you.” By way of her focus on the studium, Campt is able to “plot seriality as more than simple repetition,” more than an aesthetic dullness that prompts no immediate affect, but rather as an “integral part of complex patterns of cultural enunciation.”18 These are pictures that make sounds, pictures that cumulatively shout, musics that moan.

We can at least say, therefore, that Barthes’s rejection of sound, if taken as a rule, and certainly within the parameters of Camera Lucida, suppresses the sociality of photography by doing away with its materiality, along with the gendered and classed and racial history of that materiality, in order to fashion from its utopic eradication his own “Absolute subjectivity.” Moten argues, in “Black Mo’nin’,” that “the necessary repression—rather than some naturalized absence—of phonic substance in a general semiotics applies to the semiotics of photography as well.” Thus in Barthes the yearning to “try to formulate the fundamental feature, the universal without which there would be no Photography” (9), succumbs to “the semiotic desire for universality, which excludes the difference of accent by excluding sound in the search for a universal language and a universal science of language.”19 Those things which Barthes seeks to disqualify and relegate—noise, shouts, sounds—constitute deviations from the unilateral order he seeks to impose on photography. They are deviations in which, or through which, sociohistorical meanings enunciate themselves. As Moten writes, this universalizing desire

is manifest in Barthes as the exclusion of the sound/shout of the photograph; and … in the fundamental methodological move of what-has-been-called-enlightenment, we see the invocation of a silenced difference, a silent black materiality, in order to justify a suppression of difference in the name of (a false) universality.20

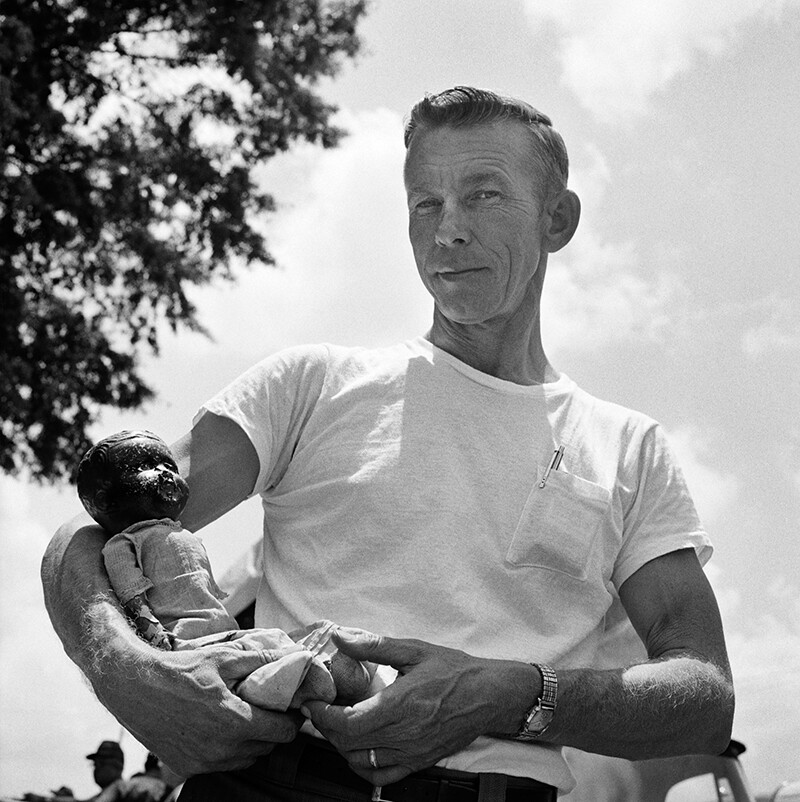

Mamie Till is held by her future husband, Gene Mobley, as she sees her son’s brutalized body. She insisted on her son’s casket being open so that the world “could see what they did to my baby.” Photo: David Jackson. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Let us say that the relationship between the matched edges of the lost slave-master photograph and the Nadar portrait of de Brazza shown in Camera Lucida makes a palindrome—that they form the two sides of an edgeless mirror. Moten’s essay uncovers yet another palindromic figure in the relationship between Barthes’s retention of a photograph of his dead mother, and Mamie Till Bradley’s insistent exhibition of a photograph of her dead son, Emmett Till. As Moten writes, Till’s “casket was opened, his face shown, is seen—now in the photograph—and allowed to open a revelation that first is manifest in the shudder the shutter continues to produce, the trembling, a general disruption of the ways in which we gaze at the face and at the dead.”21

In the image of young, dead, lynched Emmett Till, affect and corporeity abound but are irreducible to “the ego’s ancient sovereignty”—irreducible to property. Bradley’s exhibition of her murdered child constitutes both a surrender and a claim, a release and a carrying, a gesture of showing that reckons directly with the violently differentiated racial histories of seeing and being-seen, that generates shouts and echoes and moans in which we might hear and look upon “the oppressive ethics and coercive law of reckless eyeballing.”22 Mamie Till Bradley understands that her insistent exhibition of the photograph of her dead beloved makes possible a kind of community formed in what Moten, by way of Nathaniel Mackey, calls “wounded kinship,” and thus that “that leaving open is a performance. It is the disappearance of the disappearance of Emmett Till.”23 In indefatigable refusal of sheriff H. C. Strider’s attempts to prematurely entomb Emmett Till’s lynched and broken body in Mississippi,24 Mamie Till Bradley’s ongoing photographic performance ensures that

Emmett Till’s face is seen, was shown, shone. His face was destroyed (by way of, among other things, its being shown: the memory of his face is thwarted, made a distant before-as-after effect of its destruction, what we would never have otherwise seen). It was turned inside out, ruptured, exploded, but deeper than that it was opened. As if his face were truth’s condition of possibility, it was opened and revealed. As if revealing his face would open the revelation of a fundamental truth, his casket was opened, as if revealing the destroyed face would in turn reveal, and therefore cut, the active deferral or ongoing death or unapproachable futurity of justice.25

Consequent upon that showing in grief, that showing of the beloved body as grief—as wound—Till’s photograph “carries its referent with itself” (5). For Moten, Till’s photograph

bears the trace of a particular moment of panic when, “under the knell of the Supreme Court’s all deliberate speed,” there was massive reaction to the movement against segregation … So that the movement against segregation is seen as a movement for miscegenation and, at that point, whistling or the “crippled speech” of Till’s “Bye, Baby” cannot go unheard.26

The cacophonous utterances made present to us through this photograph are indivisible from the history out of which it emerges, and, as Moten writes, this “means we’ll have to listen to it along with various other sounds that will prove to be unneutralizable and irreducible.”27

Both Campt and Moten model a relationship to affect, and to the photographic image, that refuses the proprietary and exclusionary claiming of history. If in the latter stages of Camera Lucida, Barthes recognizes that “the time when my mother was alive before me is … History,” and that “no anamnesis could ever make me glimpse this time starting from myself” (65), he nevertheless refuses continually to begin in commonality with others, in a history that is irreducible to proprietary claims. For Barthes, in his solipsistic isolation, photography is valuable in the extent to which it can give him “a sentiment as certain as remembrance” (70), but that remembrance, and thus photography’s foundational relationship to memory, is essentially private, subjective, and resistant to sociality. Thus, for Barthes the cherished image must be guarded in the secrecy of willful retention, as opposed to Mamie Till Bradley’s insistent exhibition. For Moten, “memory—bound to the way the photograph holds up what it proposes, stops, keeps—is given pause, because what we thought we could look at for the last time and hold holds us, captures us, and doesn’t let go.28

Against Barthes’s serial refusals of the traces of others, and of their mattering through photographs that might enact and expand memory, Kaja Silverman argues:

If to remember is to provide the disembodied “wound” with a psychic residence, then to remember other people’s memories is to be wounded by their wounds. More precisely, it is to let their struggles, their passions, their pasts, resonate within one’s own past and present, and destabilize them.29

Silverman shows incisively that in such open commonality with the memories of others, “borrowed memory” “inevitably shifts the meaning” of our own memories, so that our commitment to an openness to the memories of others enables us “to enter into a profoundly dialectical relation to the other.”30 This is crucial not just in its ethical value, but because, as Silverman notes, “to remember other people’s memories is to inhabit time”—more specifically, it is to inhabit a time that is not reducible to “the endless perpetuation of the ‘same.’”31

In Camera Lucida, history serves only to fortify the white individual self, not merely to the exclusion of others, but through their expurgation from the scenes in which they appear, so that the husked-out shells of images might better accommodate Barthes’s imperious needs, likes, and dislikes. But the radical potency of the photograph flows from the ways in which its surface is charged, suffused by the silted traces of its and our multiple itineraries. The photograph’s carnality connects us to the attenuated presence of others, who appear to us now—in this ineffably lapsed present-ness—in a temporality that always exceeds the moment of our encounter, and the parameters of our individual lives.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Scottsboro, Alabama, 1975 from the book Liberty Theater (MACK, 2018). Copyright: Rosalind Fox Solomon. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Rosalind Fox Solomon.

6.

In closing, like Barthes we might return, by way of his memories, to his treatment of that James Van der Zee portrait from 1926. In it, he (mis)identifies the necklace worn by a “solacing Mammy” as “a slender ribbon of braided gold” (53). He writes that “it was this same necklace … which I had seen worn by someone in my own family, and which, once she died, remained shut up in a family box of jewelry,” the property of “this sister of my father” who “never married, lived with her mother as an old maid,” of whom Barthes writes “I had always been saddened whenever I thought of her dreary life” (53).

As Margaret Olin has shown, the “reason that Barthes could only have recognized this punctum when he wasn’t looking at it, is that the detail he picks out, the slender ribbon of braided gold, is not there. The lady wears a string of pearls, as does her seated relative.”32 It transpires that the three African Americans in Van der Zee’s studio portrait are “in fact … the maternal aunts and uncle of their photographer—Mattie, Estelle, and David Osterhout.”33 Barthes dubs Estelle Osterhout the “solacing Mammy,” and his misidentification of this “mistaken detail,” to follow Olin, leads “Barthes to the center of pain in the photograph,” which is to say back to a family photograph of his own in which his paternal Aunt Alice is stood in the precise position Estelle Osterhout occupies in Van der Zee’s picture.34

Olin argues that in his delayed response to Osterhout, in his discovery there of her “whole life external to the portrait” (57), Barthes in fact “covers up the dreary life of a woman who, in her utter respectability, is utterly pitiable,” displacing Osterhout as a specific being in order to transpose into her stead his sad Aunt Alice.35 Olin continues that a “chain of photographs leads Barthes, searching from image to image, to the unexpected discovery of himself,” and that “he was Aunt Alice as well.” She asks: “How different was this woman, who never married but lived alone near her mother all her life, from Barthes himself, who, as he does not fail to tell us later in the book, lived alone with his mother until her death, two years before his own?”36

Here, Barthes effects successive transpositions of subjectivity which, step by step, eradicate blackness and femininity, in order that such erasure—catalyzed by the incubatory given-ness of black femininity—might “raise a white brood,” as Shawn Michelle Smith has it.37 This is that “phenomenon of marking and branding,” of which Spillers wrote, which finds “its various symbolic substitutions in an efficacy of meanings,” the rehearsal of which prepare black flesh (as distinct from the white “body”) as the ground for further visceral woundings and physical acts of erasure.38 This symbolic and rhetorical license normalizes the exercise of anti-black and ungendering violence in the elaboration and naturalization of white subjectivity, and it is given voice in Barthes’s imperious declaration, immediately following the aversion of his gaze from Lewis Hine’s photograph of “idiot children in an institution,” that “I am a primitive, a child—or a maniac; I dismiss all knowledge, all culture, I refuse to inherit anything from another eye than my own” (51).

Estelle Osterhout’s comportment, her strapped pumps, her low-slung belt, her pearl necklace, her instantiation in the group portrait of the resiliency of familial bonds between African Americans entrapped in what Saidiya Hartman has aptly termed “the afterlife of slavery,”39 registers for Barthes only as an occasion for an act of expropriation exclusively concerned with his “Absolute subjectivity.” He thus dismisses the fact, central to Campt’s powerful revaluation of black family photography, that such portraits also mark quotidian practices of “reassemblage in dispossession,” in which acts of black “self-fashioning” that occur under the constraints of white supremacy effect “everyday micro-shifts in the social order of racialization that temporarily reconfigure the status of the dispossessed.”40 As Campt writes of the audible hum that surfaces in the Dyche archive of family portraits, the

quotidian practice of refusal I am describing is defined less by opposition or “resistance,” and more by a refusal of the very premises that have reduced the lived experience of blackness to pathology and irreconcilability in the logic of white supremacy. Like the concept of fugitivity, practicing refusal highlights the tense relations between acts of flight and escape, and creative practices of refusal—nimble and strategic practices that undermine the categories of the dominant.41

In the Dyche archive, Campt discerns the itinerary of a practice of refusal that instantiates black feminist futurity, which insists on living now “that which will have had to happen.”42 Barthes’s rejection of black refusal—his incapacity to think photography’s important role within the constrained conditions of black sociality—is consonant with the grammar of enslavement, in which, as Spillers wrote, the “captivating party does not only ‘earn’ the right to dispose of the captive body as it sees fit, but gains, consequently, the right to name and ‘name’ it,” and to do so within that “grid of associations, from the semantic and iconic folds buried deep in the collective past, that come to surround and signify the captive person.”43 Thus, when Barthes returns, a third and final time, to Estelle Osterhout, in the final pages of the book, she still serves him, not as the black incubator for white familial regeneration, but in this final instance as a pretext for the expiation of his (white) guilt, figured as pity descending from above.

I then realized that there was a sort of link (or knot) between Photography, madness and something whose name I did not know. I began by calling it: the pangs of love … Is one not in love with certain photographs? … Yet it was not quite that. It was a broader current than a lover’s sentiment. In the love stirred by Photography (by certain photographs), another music is heard, its name oddly fashioned: Pity. I collected in a last thought the images which had “pricked” me (since this is the action of the punctum), like that of the black woman with the gold necklace and the strapped pumps. In each of them, inescapably, I passed beyond the unreality of the thing represented, I entered crazily into the spectacle, into the image, taking into my arms what is dead, what is going to die, as Nietzsche did when, as Podach tells us, on January 3rd, 1889, he threw himself in tears on the neck of a beaten horse: gone mad for Pity’s sake. (116–17)

What (re)sounds for Barthes is not the unknowable but irrepressible presence of another person, but the music of his pity—a resonance of his own affective (and here parental) relationship to the dead, to what is going to die: that which he “takes up into” his arms as he goes mad for pity’s sake. The photograph of the Osterhouts, which, like all photographs is “at once evidential and exclamative,” for Barthes “bears the effigy to that crazy point where affect (love, compassion, grief, enthusiasm, desire) is a guarantee of Being” (113). For Barthes here, others live in images only to the extent that his affect resurrects them, and never on their own terms but along the lines and within the limits of his feeling. In the end, pity names the force and the hierarchical direction of Estelle Osterhout’s resurrection in Camera Lucida, and it finds no terms for the ongoing acts of living in which her portrait participates.

If, at the close, Barthes has been imploring photography to yield up a picture in which “someone in the photographs were looking at me!” with photography’s distinctive power “of looking me straight in the eye,” he declares himself nevertheless invested in discovering an encounter in which he cannot be certain that in that looking, the person “was seeing me.” He is after a photograph infused with an “an action of thought without thought, an aim without a target,” the appearance in a photograph of “an intelligent air without thinking about anything intelligent.” (111–13) Barthes is in search of, and can only valorize, a photographic encounter in which his thought alone is certain and active, in which his “love, compassion, grief, enthusiasm, desire” acts as the sole and unilateral “guarantee of Being.” His absolutist subjectivity still violently requires and seeks to possess its corresponding objects, and they must be silent, in order that the musics of his pity might more clearly be heard.44

As Moten writes:

The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist. Blackness—the extended movement of a specific upheaval, an ongoing irruption that anarranges every line—is a strain that pressures the assumption of the equivalence of personhood and subjectivity. While subjectivity is defined by the subject’s possession of itself and its objects, it is troubled by a dispossessive force objects exert such that the subject seems to be possessed—infused, deformed—by the object it possesses.45

Blackness refuses Barthes’s silencing of difference, and I would argue that that refusal suffuses and “anarranges” his desire at Camera Lucida’s close. It can be registered in that noise, that distortion with which his plea for the attention of others gives way to a need that that attention seem mindless; it can be heard in what Moten dubs the “silencing invocation”46 of the photograph’s soundlessness as that imperative gives way only to the music of Barthes’s own pity; it is audible in Barthes’s incapacity to reckon with a form of being that organizes its activity (we might say its flesh) within the visible world so as to look “without appearing to see” (111)—to look without reckless eyeballing, to appear to have “no impulse of power” (108): to look oppositionally from the standpoint of an abjected object.47 Blackness, under the subjections of white supremacy, occupies precisely these diametric extremes, and its social practices suspend and even collapse their polar divisions.

It has been the station, lot, and gift of black life—within the United States and beyond it—to see without seeming to look, to look without appearing to know, to think without the appearance of intelligence, to hide radical thought in plain sight. This is Frederick Douglass’s account of the “wild songs” of the old woods on the plantation, in which the prophetic sounds of liberation and lament were composed in stride, through “thought that came up, came out—if not in the word, in the sound,” “consulting neither time nor tune.”48 This is the genius of the cakewalk, whose insouciant, insubordinate, and satirical mimicry of plantation pomp “remade the culture that caged us.”49 This is the resistant opacity of capoeira, which veiled martial discipline under the masquerade of degenerate dance. These polyvocal, syncretic, and collaborative black social practices emerge from precisely the improbable antinomies that Barthes fails to reconcile at the close, except through the ontology of the photograph (115). His unrequited desire for a look without looking, a thought without thinking, an attention without perception describes both the skill and sufferance of precisely the black life that he utterly fails to see in the various photographs he shares.

In Camera Lucida, blackness, and its objects, exert a force that suffuses and distorts the claims that Barthes’s subjecthood depends upon, so that in his grief-stricken and egotistical attempt to refashion himself from his photographic objects, the inescapably racialized and fundamentally unethical grounds of visibility irrupt continuously and destructively into the ahistorical vacuum in which he endeavors to work. The book is utterly unthinkable in the absence of global histories of enslavement, and of hegemonic white normativity and embodiment, and yet it is unable to think either the “that-has-been” or the “there-she-is!” (113) of these phenomena in their indivisible entanglement with the images Barthes claims. If I could adapt a formulation from Jonathan Beller’s incisive work, wherein he quotes Regis Debray, I would say that Camera Lucida, and its ongoing canonical stature, is emblematic of the dangers that arise from the unacknowledged organizing force of whiteness “operating in the silence of theory.”50

Barthes leaves Estelle Osterhout cradled in his pitying arms in grief at his own mortality. She is alive as pitiable, which is to say she is dead already: both socially dead, and incapable in his eyes of meaningful acts of living. She is left without speech, or, in French, “sans parole.” We encounter her in Barthes’s texts, following Spillers’s haunting formulation, beneath “markers so loaded with mythical prepossession” that there is no easy way for her “to come clean.”51

“Parole” is an old military term connoting a watchword, or a password to intelligibility and recognizability on the field of battle. To be without it is to risk one’s life: it is to traverse a field organized by violence without the capacity to identify oneself verbally as being on the right side. Those possessed of “la parole” have executive capacity, the power to make performative and constative statements: the power to act in and on reality through their mere speech alone. In contemporary English usage, “parole” marks a conditional release from captivity or incarceration—it signals a qualified freedom policed by state power, one premised upon “good behavior” and subject to arbitrary inspection or unilateral withdrawal. There, as elsewhere in its contemporary peregrinations, “parole” is one’s word of honor, one’s oath, a necessary and sufficient certificate of one’s capacity to participate in the ethical agreements that undergird civil society.52

Here at the close, we find Osterhout cradled in silence. She is “unvoiced, misseen, not doing, awaiting [her] verb,” as Spillers has written of black women, and I would submit that it is precisely here, within the terrain and invention of black feminist theory, that our reparative work should begin, because Barthes’s pity leaves me speechless.53

Continued from “Sans Parole: Reflections on Camera Lucida, Part 1”

Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” in diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 68.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Hill and Wang, 1981), 4. All subsequent page references to this source are given inline. All emphasis in original unless otherwise noted.

Fred Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning, ed. David Eng and David Kazanjian (University of California Press, 2003), 66. Kaja Silverman, The Threshold of the Visible World (Routledge, 1996), 164.

Tina Campt, “The Lyric of the Archive,” in Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Duke University Press, 2012), 130.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 134.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 134.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 135.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 135.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 135–36.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 136.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 136.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 136.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 139.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 59.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 172, 173, 174. Emphasis in original.

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 174. Emphasis in original.

Fred Moten, Black and Blur (Duke University Press, 2017), 106. Emphasis mine. See also Denise Ferreira da Silva, “On Difference without Separability,” in Incerteza Viva: 32nd Bienal de São Paulo (Fundaçao Bienal de São Paulo, 2016).

Campt, “Lyric of the Archive,” 139.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 68.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 68. Emphasis in original.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 64.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 64.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 64.

See Jacqueline Goldsby, “The High and Low Tech of It: The Meaning of Lynching and the Death of Emmett Till,” Yale Journal of Criticism 9, no. 2 (Fall 1996).

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 63–64.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 61.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 61.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 64.

Silverman, Threshold of the Visible World, 189.

Silverman, Threshold of the Visible World, 189.

Silverman, Threshold of the Visible World, 189.

Margaret Olin, “Touching Photographs: Roland Barthes’s ‘Mistaken’ Identification,” in Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida,” ed. Geoffrey Batchen (MIT Press, 2009, 2011), 79.

Shawn Michelle Smith, “Race and Reproduction in Camera Lucida,” in At the Edge of Sight: Photography and The Unseen (Duke University Press, 2013), 27.

Olin, “Touching Photographs,” 79.

Olin, “Touching Photographs,” 80.

Olin, “Touching Photographs,” 83.

Smith, “Race and Reproduction in Camera Lucida,” 34.

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 67. Emphasis in original.

Hartman writes: “If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment. I, too, am the afterlife of slavery.” Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2007), 7.

Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017), 60.

Campt, Listening to Images, 32. Emphasis in original.

Campt, Listening to Images, 17. Emphasis in original.

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 69.

We should recall here Barthes’s fanciful claim about his mother, that “during the whole of our life together, she never made a single ‘observation’” (69). His claims, throughout Camera Lucida, and the possessive and declarative force of the punctum as a device for naming and valuing, are all consonant with this proprietary, exclusionary, and exclusive impulse. Together, these common factors in the book model a (white) perceptual subject who comes fruitfully into themselves through acts of dispossession. See Elisa Marder The Mother in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Psychoanalysis, Photography, Deconstruction (Fordham University Press, 2012).

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 67.

See bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Routledge, 2015).

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave. Written by Himself (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), 25.

Hafizah Geter, “Black Phenomena: On Afropessimism & Camp,” BOMB, no. 157 (Fall 2021) →.

The original text reads “… in the silence of technologies.” Jonathan Beller, “Camera Obscura After All: The Racist Writing with Light,” chap. 6 in The Message Is Murder: Substrates of Computational Capital (Pluto Press, 2018), 99.

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 65.

Oxford English Dictionary, online ed., 2019.

Hortense Spillers, “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words,” in Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, ed. Carole S. Vance (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), 74.

With thanks to Ariella Azoulay, Tina Campt, David Campany, Patty Keller, and Fred Moten.