The Old Woman

July 22, 2009. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

She arrives in the late morning and takes a corner in the gallery—away from the café, from the windows, from the tourists passing through. There, she won’t be disturbed as she attends to her affairs. She circles her chair, rummages through her coat, stares at a detail on the floor, and another on the wall. She’s murmuring. The guard is used to it: another crazy old lady.

She sits, then quickly stands. She shrieks. She freezes. She falls silent.

Can someone have a stroke standing up, the guard wonders as he races towards her. She’s buckled over, halfway to placing her hands on the back of the chair. Immobile, as if transfixed by terror. But that doesn’t really describe it. That doesn’t nearly explain why the tourists are also shrieking.

The gallery is filled with spectacles that don’t elicit the same response. Lucretia plunges a knife into her chest after Sextus Tarquinius rapes her. Count Ugolino, imprisoned with his sons and grandsons, must choose between starvation and cannibalism. Their pain, though rendered at human scale, is marble—remote. Hers is magnetic—her body, absorbing the colors around her: the red of the bricks, the grays of the stonework, the blackened and pearled hues of the sculptures. Though it might sound like camouflage, she’s not disappearing. If anything, she’s the only thing people can see.

*

A church in Chicago once acquired a small statue of the Virgin Mary, carved in linden wood. Two weeks after its arrival, the statue began to weep.

Thousands flocked to the statue, intent to see a miracle that would never be repeated. A man fired three shots in its direction, as if to dispel its hold on the masses.

Take away the assassination attempt, and this could describe the scene at The Met in the days following the event. The EMTs and conservators had come and gone, neither able to confirm the animacy of the petrified woman. If the museum had concerns about keeping her on view, then the public response must have calmed them. Visitors, at least initially, seem disinclined to draw the worst conclusions: that a person may have died in the museum, that the museum is a dangerous place where this could happen to you. No, they come in droves: most, to gawk at the world’s latest bafflement—and a few, to extract something of the phenomenon for themselves. The guards do their best to ward off curious fingers. The woman is soon defended by stanchions.

Little can be learned about her. If she was carrying identification, then it petrified along with everything else. The photographs shared by media don’t produce any leads. Nobody comes forward.

*

The timing is particularly good for The Met. The museum’s endowment shrank by 28 percent between last summer and the first of the year, and it recently laid off seventy-four employees. A “painful but unavoidable consequence of the global financial crisis” is how chairman James R. Houghton put it. Certainly, the institution would discuss what to do with the woman; in the meantime, what’s the harm with keeping her on view?

As attendance numbers continue to rise, each day breaking the record set by the last, the critics come out of the woodwork. Misery, according to some, caused the woman to petrify. Her pose tells a story of hardship and debility, of profound existential distress. She should be moved to a place equipped to compassionately care for her—not kept in an institution that profits off her pain. The trouble is that nobody can agree on what that place should be. As she was once human and might (eventually) return to that state, is it a care home or eldercare facility? She’s become an object of significance in the city’s history, so is it the Museum of the City of New York? The New York Historical Society?

Others believe the woman chose to transform in the museum. Guards had seen her there before; they knew she liked that corner of the gallery. Removing her might go against her wishes.

This position finds support from a prominent cultural critic, albeit for a somewhat different reason. We’re missing the point, she writes, by attempting to rationalize this event or dwell in the details. The mystery of petrification is like the blindness that guides the hands of the greatest artists. The woman is artist and artwork. She belongs in the museum.

There’s something powerfully democratic about this claim, which isn’t lost upon the public. The museum is no longer a citadel of “high culture” that we visit for edification, but a place where the average person can be respected as art.

There’s also something threatening—at least to the gatekeepers. A random woman does a freak thing in a museum, and the media gets in a tizzy. How dull the other sculptures seem by comparison! How derivative, the mimetic arts! Here, instead, a woman who isn’t a sign, an approximation, a sex worker done up as an ancient heroine. She is pure presence: just whom she appears to be.

The avant-garde went about it entirely wrong with their huffing and puffing. The museum not only stayed standing but entombed their work in the process. All it took was a random woman doing a freak thing to send tremors through the foundation. And she walked in. She just walked in.

*

A month after the petrification, public opinion is still split. There hasn’t been an outcry, or not one large enough for The Met to feel pressure to remove her.

The woman is not mentioned on the museum’s website, nor in the map of the galleries—decisions made to minimize the spectacle. The wall label placed nearby describes only the date and circumstance of her transformation.

A curator once told me that she refers to wall labels as “tombstones.” The woman may eventually reanimate, but for all intents and purposes, the things that enter museums are categorically dead.

*

I went to see her a few weeks after she petrified—first thing on a Tuesday morning, when I thought the crowds might be thin. I had read the criticism, seen her image countless times. I was hoping to learn something myself.

What I can say is that I didn’t see misery, despite how her body buckled. It felt like the story was told on the surface: the skin pulled taut at the sides of her mouth, her shoes splattered with the colors of the floor.

When Roger Caillois wrote about insects that mimic their environments, he called the phenomenon a “temptation by space.” He observed something similar in people with depersonalization disorder. Alongside the “instinct of self-preservation,” Caillois suggests, is another of renouncing, forgetting, flight: the desire to escape oneself—to disappear into the world.

When I looked at her, I imagined that she’d been tempted. She’d renounced part of herself, slowed her existence to a stop. She’s become part of the museum in a way no object could.

The Museum Guard

A woman petrifies in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the world skips a beat. It seems like the stuff of myth: a way to explain why certain rocks bend and twist, a warning against vanity or lust. But to The Met, with its displays of human mummies, she is somewhat familiar.

The museum began collecting Egyptian culture in 1874, coming to amass about twenty-six thousand objects. Of the mummies, none is more striking than Kharushere, a doorkeeper of the House of Amun who lived in the Third Intermediate Period: 825 to 725 BC. For display purposes, Kharushere has been removed from his cartonnage and coffins, which stand upright beside him. His body, wrapped in a sheet and bandages, lies on a slab that traces his contour. The effect is peculiar and a bit difficult to describe … It’s like the museum has cut him a shadow.

Down the hall are three mummies from a later era, whose wrappings are decorated and covered by masks. Kharushere received no such treatment. There are some tears in the sheet that covers his head, which resemble an eye socket and harelip, but to “see” him, one must look at the faces carved on his cartonnage and coffins. Each is presented in a manner that implies a relation to the rest—the outer coffin is open, the contents are arrayed in descending scale—but somehow, nothing connects. The human body lying there, wrapped yet exposed, whose preparations for the afterlife have been compromised on our behalf: this overwhelms the scene.

*

A few months after the woman petrified, a man begins to come to The Met. He sits on the bench in front of Kharushere. The gallery is a cul-de-sac, off the main hallway, which never attracts many visitors. When he was a guard, it was his favorite place in the museum, where he could have a minute to himself.

The Met took a hit in the Great Recession; he was one of the seventy-four who lost a job. This shouldn’t be that tough for him, as he’s only in his thirties. But it isn’t the moment to be looking for work. The road doesn’t rise to meet him. After weeks of applications and interviews that go nowhere, he finds himself returning to the museum. At first, he wanders the galleries, chatting with colleagues like he used to. Soon, he withdraws. The most the guards receive is a brief nod, at opening time, as he heads to Kharushere’s gallery.

For him, it happens differently. He doesn’t make a noise or dramatic gesture but sits completely still. Perhaps this is why the guards don’t notice, or perhaps they leave him alone because they feel sorry for him. By closing time, when he’s asked to get up, it’s already too late. His petrification is underway.

*

A young girl stands in front of the petrified man. One hand is in her mother’s; the other picks at the hem of her dress.

After what feels like an eternity, she says:

“Daddy?”

The scene is part of a 60 Minutes episode that airs a few weeks after his petrification. By this point, the world has learned about his wife and daughter, who weren’t aware of the layoff. On the days he spent looking for work, or sitting in the front of Kharushere, they assumed he was still guarding The Met. His friends see it as a matter of pride: the embarrassment of losing his job, the failure to provide. He would have told them the truth after finding something new. There’s no way he wanted to petrify. He wasn’t the type to run away from a difficult situation. He would never “abandon” his family.

The wife and daughter are the emotional throughline of the episode, but they alone don’t account for its significance. Though 60 Minutes isn’t exactly “cutting-edge” in 2009, it gives the first thorough report of the petrifications.

In one segment, conservators sand sections of the man and woman’s petrified garments. Analysis reveals that the samples are made entirely of calcium carbonate. Snails and shellfish secrete this material to fortify their soft bodies. If the man and woman have done something similar, then they may be alive and intact just beneath this hard outer layer.

What the sample analysis can’t explain is the pigmentation of the calcium carbonate, speckled with the colors of their surroundings. Here, there’s less recourse to science, which is still trying to determine how shells get their colors—what roles diet, heritability, and environment might play. There’s one case that seems relevant: the cowries that live and feed on coral, their shells assuming its tints. A person who feeds on the museum becomes like the museum … like a statue … like a mummy …

In a later segment of the show, technicians take mobile X-rays of the petrified. The results are startling. In place of the usual blacks and grays—the air, muscle, fluids, and fat—there’s only white. The bodies of the man and woman are flatly, graphically white. Calcium carbonate from top to toe.

Despite this finding, the “shell theory” persists, albeit in a metaphoric sense. The man and woman have withdrawn, a psychologist tells the reporter. Something affected them so intensely that an act of equal magnitude was needed.

*

For all the stories of petrification as a punishment for some misdeed, there are others of the intense feelings that can bring it about. Japanese Buddhism has the legend of Sayo Hime: As her husband’s ship departs for battle with Korea, she follows on foot, climbing the Kagami Mountain, crossing the Matsuura River. When she reaches Kabeshima Island and can go no further, sadness turns her to stone.

In another version of the legend, it’s her prayer and devotion that cause her to become, quite literally, “his rock.”

In a third, more mundane version, a fisherwoman, awaiting the return of her husband from sea, gradually petrifies.

It’s possible to visit the rocks that correspond to each version. If they were once truly human, then they’ve shown no sign of wanting to return to that state.

*

When feeling turns a person to stone, do they go on feeling? Did the father feel anything in the presence of his pleading daughter? The psychologist poses these questions, at the very end of the show, then turns to face the camera. Her final words are for the man himself:

“Return, when the shame lessens, to make amends. Delay but don’t deny life. We’ll all petrify in the end.”

*

There are different ways to bring this chapter to a close, like the different versions of Sayo Hime’s story. None feel satisfying on their own.

In one, the world is moved by the wife and daughter’s plight. Donations, large and small, come pouring in. The family is spared financial ruin, the wife able to care for her daughter without having to take a full-time job. The father stays in the museum.

In another, the world is scandalized by his actions. While the elderly woman, in her anonymity, has become a sympathetic figure, he is a lightning rod: the picture of an absentee father who leaves when the going gets tough. Attempts are made to deface him—markers and spray cans confiscated—but the guards can only be so vigilant. The museum prepares to remove him.

The wife protests, and the world again skips a beat. Her daughter has started to visit after school, sketching on the bench beside him and talking through her day. The mummies no longer frighten her—in fact, she says hello to them when she arrives.

It’s not normal, and it’s far from ideal, but somehow, it’s working. We’re still trying to be a family.

The Would-Bes

One of my favorite photographs shows a pair of desert ironclad beetles, famous for feigning death. They lie on their backs, legs bent in telltale ways. The artist, Christopher Williams, makes pictures that reflect on the nature of the medium: on photography as a means of preservation and also a tool of mortification, bringing time to a grinding halt. The genius of this image is that the beetles play along, right through the shutter release, then get back to the matter of living.

In the months following the second petrification, The Met fills with people who seem to draw inspiration from these beetles. Everywhere one goes is someone sitting intently, or contorting, or swooning: playacting their way toward petrification.

The internet is delighted. Every day, more grist for the content mill.

Consider the interview with a man found hiding beneath a stairwell, which goes stupendously off the rails when the reporter asks some basic questions. Why the elongated pose? What inspired your choice to be naked?

Consider the lawsuit by an individual who bruised his tailbone in the American Wing. The complaint of institutional negligence—a wet floor without a caution sign—didn’t square with eyewitness accounts of the plaintiff, who was seen mimicking the bronze of a falling gladiator without the slightest unsteadiness, growing distraught when nothing happened, then taking a more dramatic approach.

Consider the work gloves stuck to the side of a boulder in the Chinese Courtyard, and the conservation saga to remove them. It could have been worse: the culprit, who clung to the rock like an oversized barnacle—she hadn’t coated herself with epoxy. Somewhere in the fog of her mind, she must have sensed that it would take more than glue to become one with the stone.

*

Louis Aragon once warned that “humanity will perish” from “statuomania,” its cities choked by the likenesses of distinguished men. Between 1870 and 1911, six times as many public statues were installed in Paris than in the previous seventy years, seeming to bloom surreptitiously at night. This phenomenon, which emerged at the start of the Third Republic, served its liberal humanist agenda: there, on a plinth in most any square, was a great man of history—a model to follow. Aragon found it all to be an exercise in futility. The statues built today, he remarked in 1927, “might undergo the same fate as” the monument to Rimbaud in his hometown, which the Germans removed “for making shells” to demolish the very place it once occupied.

The proliferation of statues, writes Simon Baker, was like a form of “civic vandalism”: the appropriation of public space for ideological ends, an assault on cultured taste. It would seem that Aragon’s hostility came from the obligation to share the city with them. But the statues were no happier with the arrangement.

The title of Marcel Sauvage’s 1932 book, The End of Paris or the Revolt of the Statues, speaks for itself: the statues of Paris come to life and lead a campaign to conquer the city. Photomontages included in the book show Marshal Ney, sword raised, making his way down the Champs-Élysées; Charlemagne flanked by knights on Rue Royale; and a column of statues marching from the Louvre. Sauvage, cast as the chronicler of these events, can’t explain how the statues awoke—he wasn’t present when it happened. But he learns that they have much to say. “Life has become inhuman in the capitals of the world,” Charlemagne complains, because of the “the nervousness, the speed.” Humans weren’t “designed to play a miserable role in a chain of machines.” The statues came alive when we ossified, cogs in a thing called “modernity.” They took Paris to teach us a lesson; they’ll return to their plinths once we learn it.

*

What’s happening at The Met bears some resemblance to statuomania: two people have petrified, and now the galleries are packed with those wanting to do the same. One need not stretch the imagination very far to see what could happen next. More people succeed in transforming, and a new kind of statuary blooms, overshadowing the work in the collection. The war gods are roused to act: Mars, a fragment of a marble head; Chamunda, with her twelve missing arms; Oro, wrapped in layers of woven coconut fiber. Their revolt is coming, and when it arrives, the museum will be sealed from the inside. Every last human exiled from culture, wondering what lesson should be learned.

There are other aggrieved parties. Guards, already demoralized by the layoffs last summer, now find themselves policing the museum, sending stragglers, at closing time, on a forced march to the exit. Trustees are predicting that The Met will become a poorhouse, citing facts about the housing crisis that some of them were responsible for causing. The staff hate the optics, the lawsuit, the likelihood of more litigious idiots. Something must be done …

In March 2010, The Met announces an open call. Successful applicants—eight in a calendar year—are given three months to try to petrify. If someone makes an unsanctioned attempt, they’ll be banned from the museum for five years.

Applicants must provide a “compelling reason” for petrification. This term seems drawn from the psychologist on 60 Minutes—her belief that emotional and psychological duress cause people to transform. And it creates a fairly perverse situation where a jury of curators function like shrinks, deciding whose story is the saddest. Who deserves to escape their awful life?

Successful applicants sign an agreement with the museum. A cosigner (usually a family member) becomes the primary contact if the applicant transforms. The terms of the agreement are fascinating to read, giving language to a phenomenon without legal precedent—form to an entity that is neither employee, contractor, nor artwork. The terms were written, of course, to cover the museum’s ass.

“The applicant and cosigner waive all claims and recourse against the museum for damage incurred during display.” (In other words: you’re doing this at your own risk.)

“In the event of damage, the museum will not attempt conservation due to the limited understanding of the petrified, and of the treatment necessary for adequate repair.” (We have no clue where to even begin.)

“The applicant affirms that their petrification will not cause injury to the financial, property, or other interests of family members; personal and professional contacts; employers; service providers; and banks.” (Don’t treat us like a poorhouse. And please, pay your debts.)

*

The Met wasn’t the only museum dealing with this problem. Though the Louvre, the Getty, and the Capitoline Museums hadn’t experienced petrifications, they were filling with people eager to transform. Almost as soon as The Met announced its open call, they announced their own.

I walked through The Met a few months after the program began. Gone were the throngs of people inclining toward stony stillness; the threat of the ban kept them away. In their place was a new type of visitor—so subtle, in how they moved through the galleries, that it took time to see their tells. The way they take the empty seat on a bench and linger: not looking at anything in particular, attuned to the person beside them. How, when someone stops—to check their phone, to inspect a vitrine—they reflexively do the same. They’re searching for successful applicants.

Back in the days of Parisian statuomania, Robert Desnos wrote that if he were to make a statue in the memory of someone, it would have “no dedication, no name, no pedestal.” This could describe the people attempting to petrify, whom The Met keeps anonymous—and it helps explain this new type of visitor, intent on figuring out whom they might be. In a museum devoted to cultures past, this visitor looks to the future, shifting focus from the walls and plinths to the people on display; drawing fine lines between sitting and sitting, stopping and stopping, standing and standing; reading the habits of spectatorship, like tea leaves, for signs of petrifications to come. They’re seeking that decisive moment when, with the press of an invisible button, someone plays dead.

The Intern

She opens her diary and begins. Fuck her boss, who somehow—between running a department, planning exhibitions, and jurying the petrifications—has time to check if she’s crossing her t’s and dotting her i’s … who always finds her mistakes.

Drowning is how she’d describe the start of her internship: a slow, drawn-out type of drowning. She’s not the Type A personality that the Getty is used to hiring. And she can’t keep apologizing for being an art student, who loves to make sculpture but doesn’t do a particularly good job of researching it.

*

She begins a new entry with an apology, as too many days have passed. Work, the obvious excuse. The Bouchardon show for 2017. Cherubs, fauns—copies of copies of ancient sculptures. A game of telephone, poorly played: that’s neoclassicism in a nutshell.

The one piece worth mentioning is a monument to Louis the Fifteenth, torn down during the French Revolution. Its afterlife interests her. The only surviving part, a fragment of the right hand, was given to a man made famous for serving long prison sentences—and for his many attempts to escape.

How quickly the tables can turn, she reflects. The hand of Louis signed his sentencing order; he came to own Louis’s hand. And in a few years, it will be here, for all of LA to see.

*

She begins her entry on a positive note. The jury is coming up, so her boss has moved her from Bouchardon to the first round of application reviews. It’s a poorly kept secret that this is how the process works: an intern, usually in the Sculpture & Decorative Arts department, slims a stack of sob stories down to a size that’s manageable for the jury.

Her desk mate apologizes “on the Getty’s behalf.” This grueling, depressing task is made for a social worker, not people engaged in “serious cultural pursuits.” There’s no mistaking the air of elitism, which confirms what she suspected: the petrification program is the only interesting thing about this place.

*

She begins her entry with an applicant who caught her eye: an art historian, fresh from a postdoc, with an odd take. “To understand the art of sculpture,” they write, “one must become like a sculpture. This approach, akin to method acting, is without precedent in the field.”

A bit try-hard, if she’s being honest. Perhaps something else is at play. Could petrification be preferable to getting on the academic market? Is the art historian wagering that, if they petrify and reanimate, their job prospects will improve?

Applicants can specify a place where they want to transform. The art historian has chosen a bench at the Getty Villa near a sculpture called Poet as Orpheus with Two Sirens. She likes the way they write about it, the power they believe it holds: the poet in the center, the Sirens perched in song. Unlike Odysseus, the art historian plans to sit with body unbound; unlike his crew, with open ears. They want to be lured.

*

She begins her entry at the end of a day of gallery hopping. There was a particular one in Boyle Heights that a friend wanted her to see. It’s not a gallery in the conventional sense: nothing on view, nothing for sale, no exhibition schedule. Just a room in a warehouse and an invitation to pay what you can.

She read the piece of paper pinned to the wall—a list of terms and principles. Anyone can petrify here. No one will be collected or labeled an artwork. People deserve access to spaces like this. Petrification is a human right.

There were a handful of people in the room. She and her friend seemed to be the only “spectators”; everyone else was completely still but (as far as she could tell) in the realm of the living. A few sat on camping chairs, someone leaned on a folding stool. Mostly men in their twenties and thirties. They could be the art handlers hired to install work at a gallery like this, but when they arrived and found nothing to install, they installed themselves.

As with so much of what she encounters in the art world, there’s a gap between theory and practice. A site designed for public use is filled with white art bros. An alternative space so obscure that it attracts only an inside crowd. For all the shortcomings of the Getty, The Met, and the other big-name museums, there’s no denying that they have reach. Their applicants are diverse; she can find herself among them.

*

She begins her entry with a postscript. That space means well. It just needs to do some outreach. There are worse places in the world riding the petrification craze—preying on people who can’t get into a museum program and are desperate enough to accept any terms. These “institutions” (if you could call them that) are built in rentable, person-sized plots. If you petrify, you still have to find a way to pay.

Her friend told her something, as they drove home. A logistics company is turning empty storage units and shipping containers into places where people can petrify. No rental costs, no hidden fees: it sounds too good to be true. The CEO is a Republican mega-donor, which gives pause. There’s talk that this is his roundabout way of disenfranchising lib voters.

It sounds like a conspiracy. Her friend agreed. Petrification doesn’t happen that easily: two people in five years—both at The Met. And even if it’s true, there’s no way it could work.

*

She begins her entry in disgust. During the final round of reviews, her boss threw a surprise application into the pot; a senior curator, on the verge of retirement, wants a chance to petrify. The art historian can’t compete with this titan. He worked at the Getty for thirty years, and apparently, he can’t live without it.

*

She half-begins her entry, winding up for a rant about art-world nepotism—then stopping short. Ungratefulness is not cute.

*

She begins her entry during her lunch break, tapping away on her phone in the doorway between two galleries. The retired curator sits nearby (as requested) before the Watteau painting he helped the Getty acquire. T. J. Clark used to spend his mornings here looking at two Poussins, which were perfect for contemplation. The Watteau is crass by comparison, its four comedians, at the end of their routine, staring at the viewer expectedly—coins, please. If this is where the curator petrifies, then the most he can hope for is a bit part in the canon: the comedian running late, who missed his chance to get painted in. She doesn’t hate the idea.

*

She ends her entries with a story. On her last weekend in LA, she went back to that place in Boyle Heights. She brought a beach chair.

Some bros were in the room. Maybe they’d been there the last time; it wasn’t easy to tell them apart. She opened the chair and sat down.

Once, at the Hamburger Bahnhof, she bumped into an older woman strapped with shopping bags. She apologized to this person, who ended up being a sculpture by Duane Hanson.

If she petrifies on this beach chair, will other people make the same mistake?

She laughed at the thought of it, then waited for a shush that never came. The bros were focused on themselves.

She folded her chair and left.1

Continues at “The Petrified, Part 2”

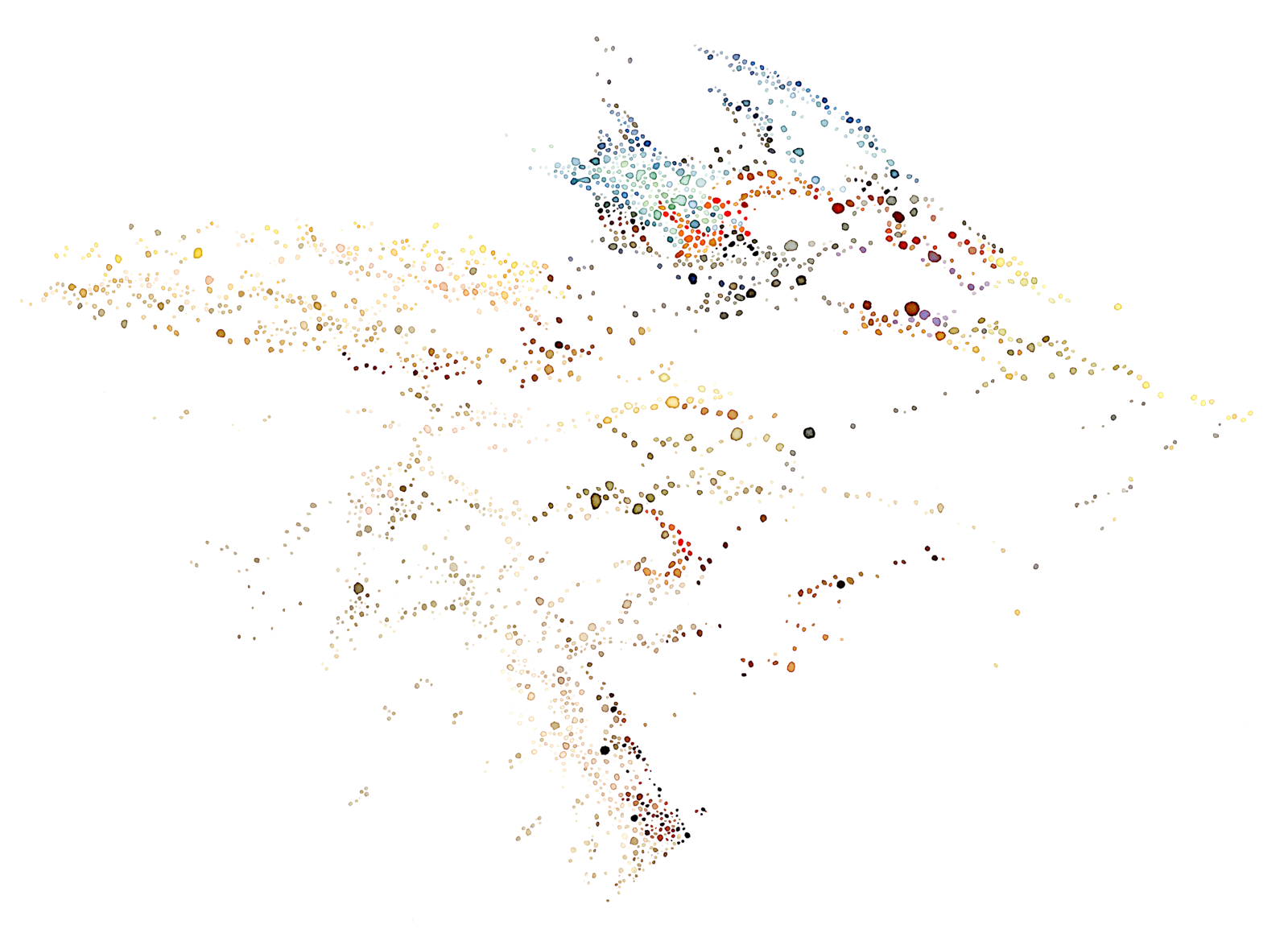

This text includes content quoted or adapted from actual events, essays, and other sources. For “The Old Woman,” see: Randy Kennedy, “Metropolitan Museum Completes Round of Layoffs,” New York Times, June 22, 2009 →; and Roger Caillois, “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,” trans. John Shepley, October 31 (Winter 1984): 16–32. For “The Would-Bes,” see: Louis Aragon, Paris Peasant, trans. S. W. Taylor (1926; Exact Change, 1994); Simon Baker, “Surrealism in the Bronze Age: Statuephobia and the Efficacy of Metaphorical Iconoclasm,” in Iconoclasm: Contested Objects, Contested Terms, ed. Stacy Boldrick and Richard Clay (Ashgate, 2007), 189–213; Marcel Sauvage, La fin de Paris ou la révolte des statues, trans. Tyler Coburn (1932; Éditions Grasset, 1983); and Robert Desnos, “Pygmalion and the Sphinx,” trans. Simon Baker, Papers of Surrealism 7 (2007). The images in this text are watercolors by the author, respectively titled The Met Fifth Avenue, Gallery 126 and Getty Center, Museum South Pavilion, Gallery S203.

Category

Thanks to Joanna Fiduccia, Elvia Wilk, and Siqi Zhu for feedback on drafts of this text. Part 2 appears in the April 2022 issue of e-flux journal.