The Psychotic Collapse of the Western Mind

We in the West are currently in the middle of a rapid disintegration of the geopolitical order that was inherited from the history of modern colonialism and that has held firm for decades. At the core of this disintegration is the mental, that is cognitive, collapse of the Western world. Sometimes I think that all the gods in the sky have hosted an assembly discussing the urgency of putting an end to their daring experiment: the human race. In a graphic-musical poem, “l’esperimento,” the suggestion is that only Calliopes, the goddess of poetry, might save humans.1

With this disintegration of the hegemonic geopolitical order, the legacy of five centuries of white colonization and extraction of the world is crumbling. As a result, the white senescent dominators, those who are used to power, are finding themselves unable to hold together the world of their own making. Thus, they accelerate the spread of violence. The senile organism of the West perceives the approach of a pandemic of psychic depression. Often in the past the reaction to impending depression was aggressive hysteria and fascism. And as is often the case, hysterical comedy results in colossal tragedy.

The viral storm that began during the winter of 2019–20 has provoked a wave of chaos masquerading as enforced order, with implications reaching far beyond the health sphere. The Covid-19 virus, which provoked increased surveillance, control, and policing, is an unpredictable and undecidable factor augmenting other forms of chaos: environmental, social, mental, and last but not least, geopolitical. When the viral black swan began squawking under the guise of a viral storm, many other black swans awoke and started squawking together in a cacophonic concert.

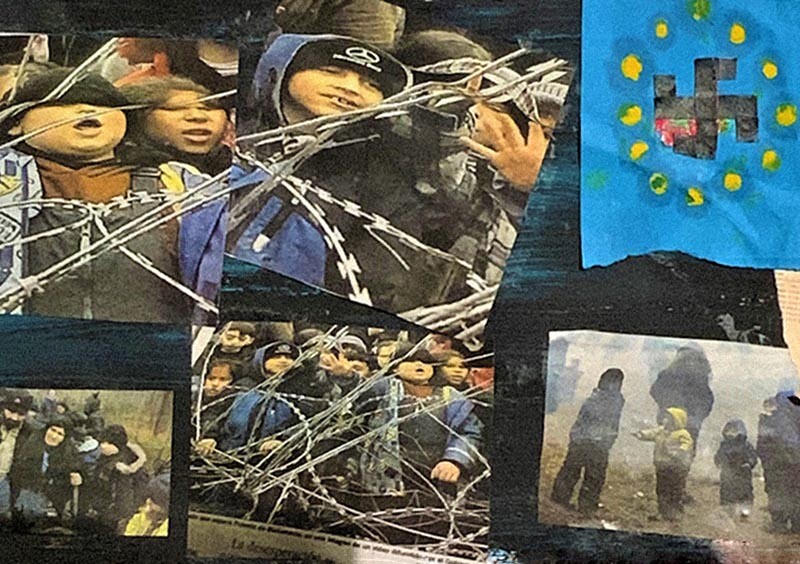

Meanwhile, more and more people in despair escape their countries that have been ravaged by Western wars and exploitation, and those waves of migration paradoxically provide a scapegoat for white racism and ethno-nationalism. Towering walls are constructed on the eastern borders of Europe, supposedly defending white civilization from its own “despair.” Along the southern frontier, thousands drown in the Mediterranean. All in all, the present European Union is becoming increasingly like the European order in 1941 when Hitler asserted the right to ethnic extermination to protect the sacred, imagined homeland of the Aryan race.

Across the Atlantic, the United States sinks into a whirlwind of political mayhem and impotent rage. The reaction to the US defeat in Afghanistan has triggered mass panic, while the Biden administration’s rescue plan evaporated quicker than it came together. Another stage for the tragedy is set: in the past few months the Ukrainian crisis has turned into an aggressive showdown. Putin reiterates that Ukraine’s military alliance with the West is a red line that should not be crossed, so he will not withdraw Russian troops deployed at the border until he is certain that NATO will not deploy men or weapons to the border. But the West cannot bend, and Biden promises to react somehow in the event of an invasion. After Kabul, however, trust in America is fading. And, ironically, this lack of trust is the very reason that Biden is obliged to not renounce a combative stance.

It is only in psychopathological terms that this geopolitical dynamic can be deciphered, as the Afghan defeat has crystallized the perception of an inevitable decline of Western supremacy. The Western mind is reacting with a panicked psychosis that could herald a suicidal act. Nothing can interrupt the dynamic of this intersection of paranoid delusions. The only thing we—as intellectuals, as activists, as therapists searching for new subjectivities—can do is prepare for chaos and imagine lines of flight.

The Unthinkable

The Unthinkable is the title of a book by Jamie Raskin, a member of the US House of Representatives from Maryland. The book came out on the first anniversary of the psychotic insurrection that brought thousands of Trumpists into the political heart of the US. The author is not just any writer; he is an important member of the US Congress, high up in the ranks of the Democratic Party. Furthermore, Raskin is a professor of constitutional law, a self-proclaimed liberal, and father of three children in their twenties. One of them, Tommy—twenty-five years old, political activist, supporter of progressive causes, compassionate, empathic—died on the last day of 2020. To be more precise, Tommy committed suicide because of long-standing depression and also (perhaps it goes without saying) because of the long moral humiliation of his humanitarian values. In his last letter, Tommy mentions his depression: “Forgive me, my illness won.” Then he adds: “Look after each other, the animals, and the global poor for me.”2

The suicide of his beloved son presents itself as an apocalypse in the mind of Raskin. Tommy’s final decision is not only an affective catastrophe for his father, but the trigger for a radical reconsideration of his political beliefs. Reading this book, I have shared the pain of a father and the torment of an intellectual. Simultaneously, I have been led to consider the depth of the crisis that is tearing apart Western culture and liberal democracy.

The book recounts three different stories simultaneously. The first is that of American fascism, the Trump administration as a kingdom of ignorance, racism, and aggressiveness. The second is Tommy, his formation, his ideals, and the constant humiliation of his ethical sensibility. The third is the effect of Covid-19 on the mind of the young generations that have suffered most from social distancing, depression, and the inability to imagine a livable future.

Raskin writes that he always considered himself “an optimist, radically optimistic about how the Constitution of the nation itself can uplift our social, political, and intellectual condition.” After the death of his son, however, his self-perception changed. His constitutional optimism is shattered by the prevailing of brutal force over the force of Reason, and by the spread of depression. He writes:

Suddenly, this constitutional optimism shames and embarrasses me … I fear that my sunny political optimism, what many of my friends have treasured in me most, has become a trap for massive self-delusion, a weakness to be exploited by our enemies. Yet I am also terrified to think about what it would mean to live without this buoyancy—and also without my beloved, irreplaceable son. The two always went hand-in-hand, and now I may be alive on earth without either of them.

Raskin’s words mark a sort of reckoning: an understanding that political and personal tragedies make evident the self-delusions intrinsic to liberal democracy. Even when faced with this break from his “sunny political optimism,” he is unable to dissociate himself from capitalist dogma. Even in the face of tragedy and death, his question remains how to reconcile American exceptionalism with tragedy, how to reconcile his newly acquired skepticism with his unfettered belief in the nation central to his depression.

Psycho-Deflation

While the geopolitical landscape turns chaotic, a key question remains: What is the landscape of social subjectivity? The pandemic deeply changed the psycho-scape, spreading depression and anxiety along with feelings of physical weakness and decreased energy. Long Covid is manifestation of this, but only the tip of the iceberg. An all-encompassing psycho-deflation emerges as the horizon of the viral age, and today’s intellectual task it to translate asthenia (abnormal physical weakness or loss of energy) into evolutionary terms. In some sense, this deflation may be the only positive trend of the contemporary era, forcing a stop to certain processes.

Psycho-deflation is the effect of the prolonged health panic, the internalization of fear, and most importantly, the change in the general consensus on the amount of space its necessary to keep between oneself and others. The need to socially distance has contributed to a mass, phobic sensitization to the body of the other, to the skin and the lips of the other. Eroticism is paralyzed and the pleasure of sociability crumbles.

It is no surprise, then, that the compulsory health measures imposed on the entire social body (to differing degrees) have created ripe conditions for biopolitical civil war. In this landscape, new political and therapeutic categories must be worked out. Psychological energy is sapped from the social body, imagination slows, and the collective body is paralyzed. This is what I mean by the term “psycho-deflation.”

But through this fear of contact that the virus has provoked, through this slowing down of social reactivity, various lines of flight are taking shape. Most people in the West are following a fascist line of escape, reacting aggressively to impending depression. However, an autonomous line of flight can also be detected and disentangled through a psychoanalytic (schizo-analytic) path: in the expanding black hole of mental suffering, one may also find the gap that precedes the emergence of a new process of subjectivation, and the visibility of a new horizon. A horizon of self-reliance, frugality, and equality, not to mention horizons of rebellion and revolt, which have also emerged since the Covid-19 pandemic first engulfed the world. But, while some of these contemporary experiences, like the Chilean insurrection and its political aftermath, are also emerging along this horizon, it would be a mistake to look to the political sphere in order to describe the possible emergence of new subjectivities. The mutation that is underway has little to do with political representation.

Much more interesting than political participation is the multifold resignation that is spreading into the ordinary business of life. Much more interesting than political consciousness is the widespread rejection of work, consumption, and procreation.

Economics and Depressive Psychosis

I follow with keen attention the views that Paul Krugman expresses in his New York Times column, because I consider him one of the most forward-looking and honest economists. But at the end of the day, he is an economist, and the epistemological limits of his science prevent him from perceiving underlying processes of change, whether social, political, or cognitive.

For an economist everything must be explained in terms of economics, in terms of market fluctuations, rising and falling wages, inflation, the interest rate—all important things, for heaven’s sake. For a working family it is very important that wages increase and that their purchasing power is stable. But if the analysis of the world we live in is reduced to economically quantifiable values, we run the risk of not understanding the essential functioning of ongoing processes. Take, for example, the column that Krugman published on December 9, 2021, titled “How Is the U.S. Economy Doing?” Krugman refers to two recent surveys conducted by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, and expresses his surprise:

The American economic landscape appears very good indeed. After the contraction of 2020, we are facing the best economic recovery in decades. Yet, reading the research results it seems that consumers are feeling very despondent, and this negative perception of the economy ends up weighing on the electoral preferences for President Biden.3

I understand very well that Krugman, a passionate defender of the Democratic Party and a supporter of Biden, regrets that his president’s performance has so far been disastrous in terms of foreign policy and in the realization of his mega-financial plan.4 But the economy is fine, says Krugman—employment has risen to pre-lockdown levels, the growth engine is running at full speed, energy consumption has risen (causing tornadoes and creating conditions for new fires, a detail that goes unremarked by Krugman). So, he wonders: “Are the consumers right? Do we have to say that this economy is bad, despite the data showing that it is very good? And if in fact it is not a bad economy, why does the majority say otherwise?”

Good question, Paul. Why do American workers, who should rejoice at the huge increase in corporate profits and the tiny increase in their wages, continue to sulk, nervous and discontented? Krugman tries to give himself an answer with the tools at his disposal:

Rising prices have certainly eroded wage increases, even if personal per capita income is still above its pre-pandemic levels. I have the impression that inflation has a corrosive character on confidence even when wages are rising, because it creates the perception that things are out of control.

So, the answer is inflation, the boogeyman of liberal and conservative economics. An economic excuse for anxiety has been found at last! But I wonder: does Krugman really think that consumers (who are not consumers, but human beings with lives that are not limited to cashing checks and spending them) are in a “bad mood” because it seems that inflation is resurfacing? In a flash of trans-economic intelligence Krugman does admit that one gets different answers when asking people “how are you?” as opposed to “how is the economy going?”

But Krugman fails to develop this intuition and returns to torment himself about the incomprehensible gap between the cantankerous mood of the crowd and the goodness of the economy. So, at the end he bursts into a cry of despair:

In a nutshell, the heavily negative judgment on the economy is in contrast to any other indicator that one can think of [economic of course]. So what is happening? It is important to keep the perspective. This is a really very good economy even if there are some problems. Do not allow the doomsayers to tell you that this is not the case.

Now, what is the point that the economist Krugman is missing? In my humble opinion, the point is that the experiences of recent years—particularly the experience of the virus and the ensuing fear and the spreading sense of mortality—have allowed people to think about life in terms that do not only concern job security, itself an almost random marker of stability.

Today, the old adage “it’s the economy, stupid” can be rephrased: “It’s the psychology, stupid.”

The psychotic collapse neutralizes the strength of the economy.

Many have joined the hordes led by Trump and evangelical preachers. Many took fentanyl and OxyContin until they overdosed. Some grab their father’s machine gun and go to school to kill half a dozen of their peers. But many others have wondered why they should devote their entire life to poorly paid (or even “fairly” paid) work when that work makes no sense, depresses you, drains you, and alienates you from others. Why live in conditions of permanent humiliation? Why not resign from all that, economic concerns be damned?

Many have organized huge strikes, like at Kellogg’s, at Nabisco, and at Columbia University, where three thousand workers went on strike for over nine weeks!5 Many others have just left: four and a half million American workers left their jobs at the end of 2020—“the Great Resignation,” as it’s being called. A sort of long Covid has installed itself at the core of the Western mind—but not only in the Western mind. In China, instead of working hard, buying a house, getting married, and having children, more and more young people are opting out of the rat race and taking up low-paying jobs—or not working at all. This simple act of resistance is commonly known as tangping, or “lying flat.”6

What Krugman cannot see, by virtue of his (liberal) economic worldview, is that in the face of death, panic, and depression, money loses its power, perhaps even its value. Money cannot revive a society steeped in depression and riddled with panic and demented fury. Money cannot win against massive resignation: as the Great Resignation goes global, we should not forget that the word “resignation” does not only mean quitting, but also renouncing expectations. Modern expectations have been dashed: democracy is an empty word, welfare has been cancelled by predatory finance. Furthermore, resignation means re-signification—giving a new meaning to pleasure, to richness, to activity, and to cooperation. This is the fresh horizon that we can discover at the end of the tunnel of psycho-deflation. An egalitarian and frugal sensitivity is the hidden perspective that is unveiled there.

In a sort of counter chant to Squid Game, the South Korean pop band BTS chants: “It’s alright to stop / There’s no need to run without even knowing the reason / It’s alright to not have a dream / If you have moments where you feel happiness for a while.”

It seems that BTS has a massive following among young people worldwide.

→.

Jamie Raskin, The Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy (Harper, 2022), Kindle.

Paul Krugman, “How Is the U.S. Economy Doing?” New York Times, December 9, 2021 →.

See, for example, Lauren Gambino, “‘It’s a Tough Time’: Why Is Biden One of the Most Unpopular US Presidents?” The Guardian, January 18, 2022 →.

“The Low-Desire Life: Why People in China Are Rejecting High-Pressure Jobs in Favour of ‘Lying Flat,’” The Guardian, July 5, 2021 →.