“Speak Into The Mic, Please” is an essay series published serially in e-flux journal. This text by Hanan Toukan is the fourth in the series, for which I have the honor of serving as guest editor.

The title of the series comes from Lina Majdalanie and Rabih Mroué’s performance Biokhraphia (2002), in which Majdalanie speaks to a recorded version of herself that is constantly reminding her to speak into the mic in order for the audience to hear her better.

Similarly to speaking to the self in front of an audience, the commissioned texts in this series attempt to look at the conditions of production surrounding the contemporary art scene in Beirut since the 1990s. The backdrop for these discussions includes a major reconstruction project in the city, international finance, and political oppression, whether under the Syrian regime or under hegemonic NGO discourses.

The texts examine interconnections between the economic bubbles and the political and cultural discourses that formed in Lebanon between the 1990s and 2015. During this period, a number of private art institutions, galleries, and museums popped up in the capital, while the city was buried under the refuse of years of intentional political mismanagement and oligarchic rule.

—Marwa Arsanios

The Participation of Iraqi artists today in an exhibition organized by a foreign institution implies an acceptance of that institution’s logic in preparing the exhibition. Participating in a foreign exhibition should not be rejected in and of itself; what should be rejected is any objective of an exhibition hosted by such an institution that is not positive, that aims at anything other than encouraging the artists and showcasing their talents. Most Iraqi artists also participated, for example, in an international exhibition held in India last year, and the Indian government has plans to organize an exhibition of exclusively Iraqi painters. But what does it mean when a colonial institution like the British Cultural Council hosts an exhibition for Iraqi artists?

—Shakir Hassan Al Said, 1953

“Al tamwyl al ajnabi”

Since Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century, Arab intellectuals have been embroiled in impassioned debates over the West’s superiority versus the Arab “lag.” From Amin Qasim’s call for the “liberation” of women to Taha Hussein’s situating of Egypt’s civilizational trajectory within that of the West, and Abed al Rahman al Kawkabi’s attack on despotism, the quest for modernity reverberated and found fertile ground in the debates around literature and poetry, and by extension the visual arts.1 As Timothy Mitchell has argued, “Modern discourse occurs only by performing the distinction between the modern and the non-modern, the West and the non-West.”2 Such distinctions, I also suggest, buttress the foundation upon which the discourse of society’s development from “backward and closed” to “open and free” has historically rested.

In 2007, the EU-funded, Mediterranean culture–focused online journal Babelmed published an article by Lebanese critic, poet, and journalist Youssef Bazzi.3 In the article, Bazzi recounts the story of Hiwar, a legendary literary Arabic journal from the 1960s, to launch an attack on contemporary local critics of global cultural funding for contemporary arts production. He derides them as adamantly and senselessly anti-Western—linking them to what he frames as the irrational and hypernationalist critics of the 1960s. In his words, the way the Arab public views its relationship to foreign funding for cultural production “is a relationship that can at best be described as ‘dubious’ and at worst as ‘betrayal,’ ‘conspiracy’ or working on behalf of the imperialist assault on the Arab nation or the ‘Zionist-colonialist project.’” He goes on to complain that “the list of charges runs through the full list of clichés that have comprised the Arab political dictionary for the last 60 years.”4 Bazzi essentially attacks what he believes to be an oppressive element in the cultural practices and discourses produced by Arab nationalism that linger years after the beginning of its decline in 1970. He ends his piece by emphasizing the impressive growth of the Lebanese arts sector—and of contemporary visual arts, specifically—under the auspices of US and European patrons since the end of the Lebanese civil war in a plea to locals to shed any lingering ill-feeling toward international funders, thereby drawing on the West versus non-West and modern versus nonmodern binaries that Mitchell underlines about the modern discourse.

Al tamwyl al ajnabi (foreign funding) is the most bandied-about term in the contemporary public discourse of cultural producers, funders, and activists in Palestine, Lebanon, and Jordan. The term refers to a set of questions posed and discussed largely by actors working in civil society organizations in the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s. The discussion centers on the advantages and disadvantages of accepting funds from foreign, but especially Western, organizations, whether governmental or nongovernmental.5

In fact, as a signifier in Arabic, the term al tamwyl al ajnabi is itself steeped in a deep imperial and neoliberal history, while the English translation of the term is neutral. As Nicola Pratt puts it, “The foreign funding debate is not about NGO financial matters, but rather about the identity of those who provide the funds (that is, organizations located in the ‘West’).”6 Central to this debate is what is termed in Arabic discourse ajindat gharbiyah or ajnabiyah (Western or foreign agendas); that is, it is not how much money a funder gives a local recipient but what is understood to be done with the money, and specifically how much this power relationship affects production. These conditions prioritize the funder’s interests over the recipient’s.7 In that sense, the foreign—or Western (the terms are often used interchangeably in public discussion)—cultural funding debate is not an empirical one based on objective facts about the impact of international funding on local NGOs. Instead it reflects the historical relationship between the Arab world and the West.8 This relationship with the West is defined by a discourse that operates in the realm of ideas that have to do with representations and identities that are essentially the byproduct of two hundred years of colonial encounters between the Arab world and the West. In the field of the arts, how this unequal relationship of power between funder and recipient materializes is hotly contested. What I mean is how recipients of funds, whether artists or local arts-supporting initiatives acting as “middlemen” with politically vested interests in the region, play a role in shaping the aesthetical and formal practices of cultural production. By extension, how do such initiatives end up influencing the way we understand the role of the artist as a critical voice for change in society?

Every Arab country inherited various forms of knowledge and technology from colonialism. When it was officially over, colonialism left behind a complex cultural and intellectual legacy that the Arab world is still trying to process.9 The region’s persistent and historical grappling with multiple identities, memories, worldviews, and associated narratives—whether religious, secular, nationalist, socialist, liberal, globalist, or cosmopolitan—means that cultural production and representation, whether for a local or global audience, inevitably become domains of contestation. In turn, this contentious politics of cultural production links to the loftier encounter with any cultural practices understood to originate in the West, as was the case with modernist poetics.10 Hence, Arab players alone do not attend to cultural production’s contentious discourse. Reflecting larger regional and global geopolitical trends, international players make themselves felt via their funding, visions, and discourses, and like local players, they assert themselves, directly and indirectly, through an intricate confluence of sect, class, and geopolitics. The debate around the contextual nature of contemporary arts production, couched as it is in a longer historical debate concerned with the problem of modernist avant-garde poetics being perceived as too “Western” by some local actors, becomes the medium through which varying ideologies express themselves and challenge each other in response to experimental aesthetics. Foregrounded in these debates are two master narratives that were almost always pitted against each other during the interviews I conducted: the myth of “modern” abstract art (and, by extension, “postmodern” conceptual and overly theorized contemporary art) versus “authentic” and “domestic” social-realist art committed to painting and sculpture as both form and content.11 These narratives are predicated on a discursive framework that demarcates roughly two categories. The first is comprised of an older group of artists, writers, and intellectuals who came of age in the era of the 1967 Arab defeat against Israel or the Naksa, embodied in the term al-muthaqaf (the intellectual).12 This category of cultural producers considers itself just as rooted in localized aesthetical practices informed by historicized understandings of art’s role in attaining justice and freedom, as they are globally attuned to questions of aesthetics. The second group is, generally speaking, younger interdisciplinary artists born roughly between the 1960s and 1980s who tend to be more conceptually informed by the theories and practices afloat in more globally connected and professionally networked sites of art making. The latter category disparages in particular what it sees as rigid concepts in art, such as liberation and justice, that have historically served the power politics of postcolonial nationalist regimes and their political rhetoric. In this framework, the binaries of authentic/modern, global/local, cosmopolitan/communal, and progressive/regressive inflame local discourses, sensibilities, and frames of thinking about the topic of international, but often especially Western, support for cultural production. This bifurcation, which was often underscored in my field interviews, conceals two sources of tension. First, how much “the modern must always have its other,” and second, how much the construction of this other is inflected with capital, class, and power, whether we are talking about the so-called authentic-local or the cosmopolitan-global.13 This inflection in turn is elided by the tendency I found for cultural actors—and this includes artists, curators, and representatives of cultural organizations—to focus on the identity rather than the politics of the funder when thinking about cultural production’s relationship to its source of funding. This focus was often accentuated in conversations when the issue of the Arab Gulf art scene was raised. One well-known artist, writer, and cultural organizer succinctly summed up this prevalent perception: “Art and patronage is a dirty business, but at least the Gulf is Arab, unlike most of the other funders we have to work with.”14

“In Beirut,” noted Daniel Drennan ElAwar, “the sponsors list of any given cultural event proudly lists the banks, foreign NGOs and other corporations that make such an importation and implantation of outside culture possible. No one seems to mind.”15 This statement exemplifies the way in which art from the Global South is systematically located within the framework of a postcolonial nationalism, on the one hand, and as the effect of a Westernized liberalism, on the other. Accordingly, notions of “importation” and “implantation” abound in debates on cultural production and al-asala (authenticity) in the modern Arab world.16 Yet such approaches are inherited from the dominant tradition/modernity debate mentioned above that too easily dismisses alternative interpretations of these tensions. Arguably modernity is not always a rude imposition or an “inauthentic appropriation,” and cultural actors in contemporary Palestine, Lebanon, and Jordan are not passive postcolonial subjects.17

After 1990, the constructed binaries—historically drawn on to explicate the encounter with the darker side of Western modernity—arguably began to be expressed in a different tone, one less prone to the rigid categorizations of the pre-1990 years that the Hiwar experience highlights. Yet still somewhat dependent on cultural actors’ transnational ties and how closely they relied on Western curatorial frameworks, the general public and many actors from within the cultural domain remained generally suspicious of the role of funding for social and cultural projects from Western sources. Yet this time, and especially after 9/11, the backdrop was what Barbara Harlow describes in Resistance Literature (2012) as the “drastic changes wrought—wreaked—in a catastrophically contested world order as the twentieth century turned into the twenty-first, relating a macro-narrative, perhaps, from colonialism, through decolonization, the polarized Cold War, a post-bi-polar world order, post-colonialism, globalization.” The new tone reflected a more violent reality of a post-9/11 world but, at the same time, a more contingent postmodern world.18

Hence, despite both funders’ and recipients’ insistence on implementing normative frames of understanding to distinguish cultural diplomacy from cultural relations, the former cannot be viewed narrowly as a tool of foreign policy under the remit of public diplomacy alone, even though it is commonly defined as “the exchange of ideas, information, art and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples to foster mutual understanding” (Cummings 2009). Instead, cultural diplomacy entails a multifaceted process of international cultural politics, realized through tools and practices of cultural policy as they manifest in various contexts. Within this framework, cultural diplomacy happens under a number of names. Its vast lexicon includes cultural relations, cultural cooperation, public diplomacy, public relations, cross-cultural exchange, and cultural development—all terms that encompass dimensions of culture as understood by Raymond Williams’s 1961 articulation of its wide meaning, processes, and significations. Depending on the lexicon in vogue since the 1990s, it has also articulated itself as developmentally attuned, civil society– and people-centered, and/or democratization in practice.19 Although a neat genealogy could be constructed for each of these terms appropriated in the language of funders, and by extension the local fund recipients, I submit that in everyday life and on a practical level they form something of an ideological miscellany. Regardless of the particularities of its individual parts, cultural diplomacy has pushed an understanding of the arts as a motor of change in a society that badly needs to reform its culture and democratize its society. By extension, the blurring of the terms “cultural diplomacy” and “cultural relations” in scholarly literature and in policy practice is one of the most insidious ways that power works in cultural production: its invasiveness renders funders and fund recipients oblivious, unwittingly or not, to the fact that the funding of cultural production is always an instrument of power, even if it is intercepted by local actors—or, to borrow from Zeina Maasri, even when those participants are not mere “passive dupes.”20

Diplomacy or Relations?

In spring 2013, I met with the director of a leading and long-established European cultural funding institution in Amman. I noted to myself that the director’s home, office, and favorite café were all located where we were sitting in Jabal al Weibdeh, one of Amman’s oldest and, in recent years, most gentrified neighborhoods. In the midst of explaining that my research reflected an interest in the local manifestations of cultural diplomacy and how they intersect with and shape artistic practices and discourses, we were interrupted by an activist, artist, and mutual friend who wanted to say hello. We all chatted briefly about her latest work with a well-known local arts collective located in quickly gentrifying downtown Amman. Before walking off to rejoin her friends, she thanked the director profusely for all his financial support and proximity to the project during the time of its making. That interaction—the whole meeting, in fact—made clear that the director was on good terms with everyone in his vicinity, from the artists he informally greeted to the barista who served him his coffee, and even the local vegetable vendor and his children, whom he greeted informally on our way out. So, it was as though he read my mind when he said to me almost immediately after our mutual artist friend left that the term “cultural diplomacy” makes him uneasy. He went on to clarify his point, stating that he regards what he and his organization do in Amman and the region more broadly as cultural relations, or more precisely, mutual cultural exchange, rather than top-down diplomacy. He was interested in knowing why I chose the term “diplomacy” to describe his foundation’s work. For him the word implied a distance from the people with whom his foundation worked, while “relations” alluded to a collective sense of ownership over a project. This was not the first time I had heard this in the field. In fact, it was one among a handful of times that a European or US funder adamantly insisted that he or she was invested in a two-way process of the exchange of culture rather than the top-down and rather archaic process of cultural diplomacy.

For these funders, cultural diplomacy harkened back to a place and time in the history of Cold War ideology that represented secrecy and espionage. They feel this comparison is a gross misrepresentation of what they do today. Perhaps I had gotten so used to meeting funders in their air-conditioned and finely decorated offices as opposed to local cafés where the interactions between the community and the funder are clearer. What the director said to me triggered my thinking about the difference between the two concepts: cultural exchange/relations (which in a way I observed him “doing” that day), and cultural diplomacy, and the way each interacts with local cultural NGOs, activists, artists, and bloggers. Yet I also came to wonder whether the precise term used to define international funding for cultural production mattered so much if essentially what each of these terms describe is a relationship defined by local arts and culture NGOs, whether they be governmental, semi-governmental, or nongovernmental, and the artists they support. As I mention in the above section, when the source of Hiwar’s funding was uncovered by the New York Times on the eve of the 1967 war, it triggered a genuine outcry that became instilled in the collective cultural memory. An understanding developed that the cultural encounter that brought the journal’s editors and writers into the sphere of US government interests was directed and facilitated by the state for ideological purposes rather than organically produced in the direct interactions between writers and artists from different parts of the world. What did the designation of al tamwyl al ajnabi (foreign funding) convey about society’s shifting perceptions of the relationship between funder and recipient within the context of the continuously growing number of foreign funded and transnationally networked arts projects? Precisely, whose interests are behind the obfuscation of the terms “cultural relations” and “cultural diplomacy,” and why and for whom does it matter that the terms are obfuscated?

At the simplest level, cultural relations may be understood as interactions that “grow naturally and organically, without government intervention—the transactions of trade and tourism, student flows, communications, book circulation, migration, media access, intermarriage—millions of daily across-culture encounters,” and cultural diplomacy as that which “take[s] place when formal diplomats, serving national governments, try to shape and channel this natural flow to advance national interests.”21 Yet in the post-9/11 era, definitions of public diplomacy, under which cultural diplomacy falls, have expressed a strong foreign-policy orientation toward mutual understanding, which is reflected in terms such as “engagement,” “relationship building,” or “two-way communications.” More, culture in the study of international relations has been defined as the “sharing and transmitting of consciousness within and across national boundaries.”22 These terms emphasize horizontal, informal, and neutral exchange, insinuating good intention, rather than top-down formal diplomacy implemented solely to influence politics. Viewed within this purview, cultural diplomacy has become a cornerstone of public diplomacy with an increased need to reconfigure soft power as a positive globalizing force.23 Hence, the new post-9/11 public diplomacy is being shaped in a context where nonstate actors such as NGOs have gained increasing access to domestic and international politics.24 The optimistic view of these new multidirectional flows of ideas, finances, and projects is that they are leading to a situation whereby states are compelled to create dialogues with foreign publics where the boundaries between foreign and domestic are less and less defined.25

Structurally reinforced by a global network that is understood to foster open spaces of dialogue across divides, these perceived changes in diplomacy’s outlook and function unproblematically construe the global as a singular space through which continuous and unfettered links of people, ideas, capital, state and nonstate actors, institutions, and cities entwine in a series of projects, events, social interactions, and cultural exchanges. Yet this nongovernmental diplomacy that is understood to embody cultural relations as opposed to top-down cultural diplomacy, leaves unpacked the power dynamics that are being obfuscated in these normative approaches to international politics prevalent in academic and policy circles. And while the literature on cultural diplomacy indicates that the term’s meaning varies according to context, a prevalent perception, especially among public diplomacy scholars, is that cultural diplomacy may be understood only within the larger rubric of public diplomacy and as a prime example of soft power—in other words, as a positive phenomenon.

However, these broad and commonly used normative definitions that depict cultural relations as distinct from and more effective as a soft-power practice than cultural diplomacy are misleading. In practice, it is the norm to conflate “culture for the purpose of flourishing cultural assets, values and identities” and “culture as a means of foreign policy and diplomatic activities.”26 These essentialist definitions dilute the analytical and categorical, yet constantly evolving and interwoven, dynamics at play in Raymond Williams’s three conceptions of culture and society, devised in 1961: (i) culture as an “ideal”—a state or process of human perfection, in terms of certain absolute or universal values; (ii) culture as “documentary” that pertains to the body of intellectual and imaginative work, in which, in a detailed way, human thought and experience are variously recorded; and (iii) culture in the “social” sense that describes a particular way of life, which expresses certain meanings and values not only in art and learning but also in institutions and ordinary behavior.27

The former director of the Goethe Institute in Beirut explained the political role of cultural funding vis-à-vis Germany’s and the EU’s interests in democratizing the region in the following way:

You cannot separate culture from democratization. In the 1960s and 1970s there was no social agenda in foreign cultural policy, it was more about entertaining people. But this is definitely finished today. Now we have strategic goals. We want to see open and democratic societies. Our focus is on the innovative and beyond the mainstream, not dabkeh [folkloric dance] for instance, and this creates irritation, especially amongst the more traditional in society. So culture contributes to pluralistic societies, something we are all working to achieve here. Yet, [this] is also quite a challenge.28

He then went on to speak of the way in which interaction with the local cultural elite was historically limited to a one-way exchange, whereby culture was transmitted from Europe to Lebanon and other countries in the region by way of exhibitions, shows, and events that brought European artists under a “purely cultural” mandate. According to the Goethe Institute in Beirut’s former director, the Institute was “bringing culture in a more fluidly defined framework rather than supporting local culture through direct funding of institutions and organizations as is done today and which is perceived by the local population as carrying more of a political overtone.”29

The director’s comments line up with logic long established among Western civil-society funders. This logic views the promotion of contemporary arts as part of a larger democratization framework among younger generations in Arab societies as having the potential to revise much of the old way of thinking. Reports like The Challenges of Artistic Exchange in the Mediterranean: Made in the Mediterranean, which read contemporary art as an “anti-fundamentalist vaccine,” are not uncommon.30 Before the Arab revolutionary process kicked off in late December 2010, interest in the arts as a mobilizer of revolutionary change from scholars, curators, and activists peaked. Young Arab artists were up against a growing Islamist conservatism because for many years, religious fundamentalism and autocratic Arab nationalist regimes had weakened the status of independent art in the public arena. Funders in this context aimed to correct this reality by bolstering “alternative” arts and encouraging Arab cultural NGOs. Their longer-term aim consisted of strengthening “the role of civil society in the promotion of human rights, political pluralism and democratic participation and representation.”31

As mentioned, only in the past twenty years has “culture” become an ever-more significant dimension of international relations because of globalization and advancements in communication technologies that reconfigure the power dynamics between different social actors. This shift is most obvious to the extent that culture as both practice and product has seeped into the language, rationale, and rhetoric of local and international civil society organizations concerned with democratization programing in the region. The perception of the potential role of civil society as agent of democratization in the MENA region, which filtered into most development assistance agencies in the 1990s and the first decade of the millennium, is often understood to lie within the purview of international development policies, rather than public (or cultural) diplomacy. Yet at the same, the genealogical underpinning of the phenomenon of international funding for societal development through local NGOs emphasizes the same “universal” political and cultural values, needs, and aspirations that unproblematically drive the mission of cultural diplomacy.

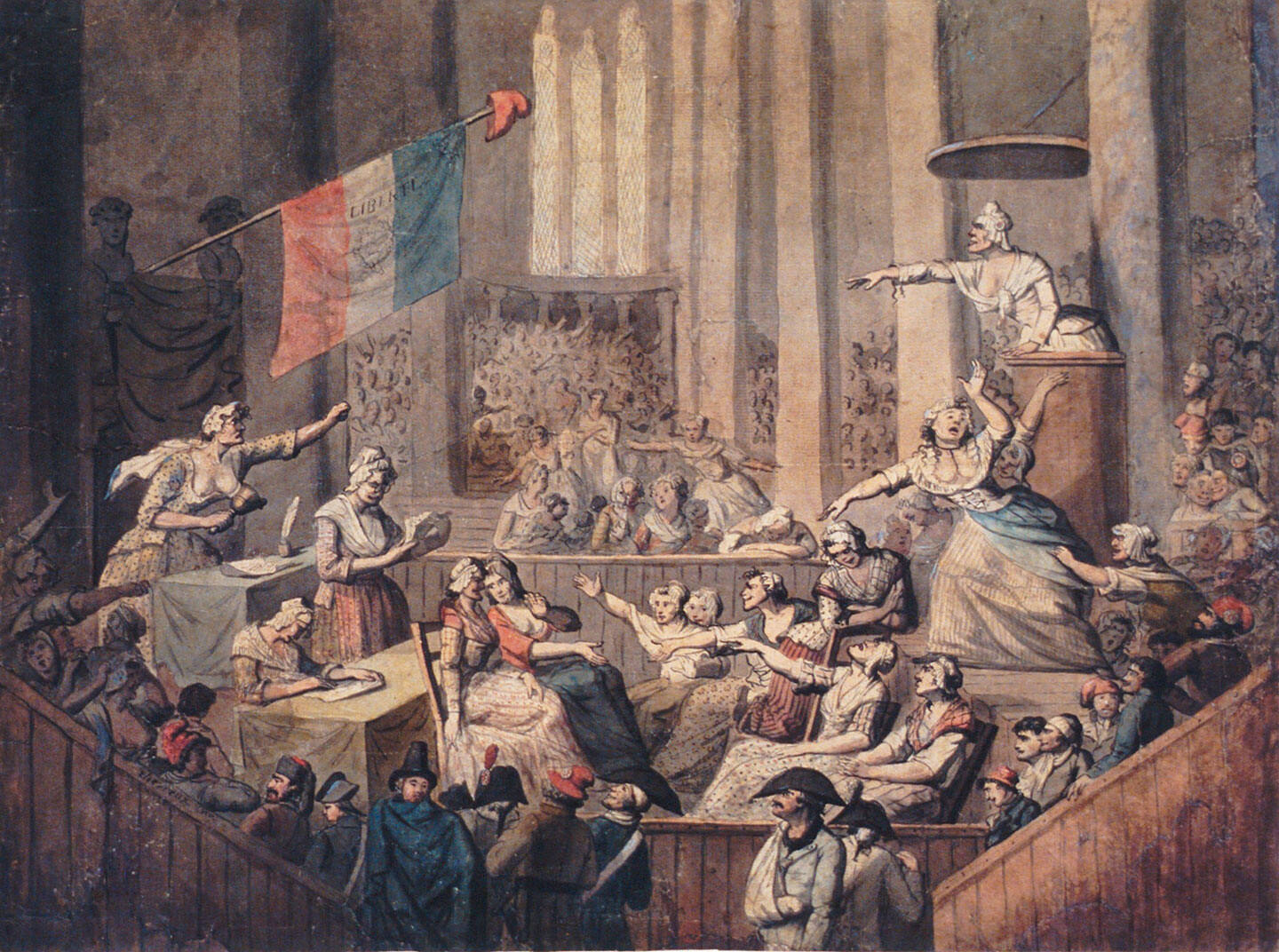

During the late nineteenth century, the institutionalized use of culture in foreign relations emerged in Europe. Grandiose world expositions and fairs during the decades of post-1848 European nationalism were some of the earliest instances of the creation of a global public space where states could strategically instrumentalize culture and cultural representation for political ends; these large events were packaged as part of a panoramic “spectacle of modernity” that dominated representations of landscapes, industries, and especially the wealth of natural resources of societies colonized by Europe.32 Although international relations theorists tend to articulate culture’s role in politics through descriptive frameworks that emphasize the functional and positive role of culture, Timothy Mitchell has unraveled how culture factored into colonial practices by highlighting modern Europe’s fondness for transforming the world into a representation through cultural exchange: the “exhibitionary complex” of cultural display (1989).33 Through his discussion of nineteenth-century Parisian expositions, Mitchell shows how the preoccupation with organizing “the view” (of non-Western culture), as he puts it, is more than merely the content of a policy or a strategy of rule in cultural imperialism. By examining how the expositions objectified the cities and people they represented through miniature Cairene streets and buildings for their “Egyptian Exhibition”—in addition to his descriptions of the astonishing reactions to these models by Egyptian and other non-European visitors who encountered them when traveling—Mitchell shows that the preoccupation is in fact an intrinsic component of the cognitive methods of order and truth that constitute the very idea of Europe itself.34

In the same way that policymakers and scholars are preoccupied with the terms used to describe the cultural relationship between the West and its former colonies, Europe is obsessed with organizing the view for the sake of categorization and display of power—which concerns Europe’s self-imaging vis-à-vis itself rather than the Arab region’s interests. As I have already mentioned, al tamwyl al ajnabi is essentially a blanket term used in public discourse to describe a relationship of power that shapes cultural representation, cultural exchange, and cultural diplomacy between two unequal sides. The discussion of what cultural diplomacy constitutes and how it plays a role in global cultural relations is essentially a discussion centered in the North American and European hallways of power. From the British Institute, to the Goethe Foundation, the European Cultural Foundation, the Institute for Cultural Diplomacy, the Academy for Cultural Diplomacy, and even the American Advisory Committee on Public Diplomacy formed in the aftermath of 9/11, and to the growing body of scholarly literature dedicated to understanding its function and potential, the term is a construct that describes the Western liberal ethic and its historical relationship of cultural exchange with the rest of the world. That same phenomenon is labeled and framed as tamwyl ajnabi, where ajnabi (foreign) evidences “Western,” rather than the more neutral and functionalist-sounding “cultural exchange” or “cultural diplomacy” taken up by Euro-American pundits, funders, and scholars.35

In the first decade of the global war on terror, despite the foundation of Cold War cultural diplomacy policy on which policymakers could draw to formulate an integrated strategy in the post-9/11 world, the Bush administration chose force as its primary tool of negotiation for shaping public perceptions.36 Cultural diplomacy waned as the administration consolidated what was already developing in the years between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the 9/11 attacks. However, it did not drop out of the culture game altogether. In the years succeeding 1999, the State Department withdrew its support for some of its most popular programs like the Jazz Ambassadors Fund, American Houses, and the Embassy Libraries that allowed for the flow of ideas and artist exchanges between the US and other countries.37 Instead, funding went toward large-scale broadcasting projects like the Radio Sawa station and the Al Hurra television satellite programs that could more directly, and with greater impact, influence the negative public opinions of the US in Arab and Muslim countries.38

For a firsthand account of some of these debates as they are expressed in art writing by artists and art critics, see Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, ed. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout (Duke University Press, 2018). See also Faisal Darraj, “The Peculiar Destinies of Arab Modernity,” trans. Anna Swank, in Arab Art Histories, ed. Sarah Rogers and Eline van der Vlist (Idea Books, 2013). Darraj’s essay explains the relevance of these debates for modern and contemporary Arab art.

Timothy Mitchell, “The Stages of Modernity,” in Questions of Modernity, ed. T. Mitchell (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 26.

Youssef Bazzi is a Lebanese poet and journalist who worked with the Saudi-backed Lebanese Future Movement political party–supported print newspaper Al Mustaqbal; as of 2019 the paper is only in online form. Bazzi is part of a generation of Lebanese leftists turned liberals in the aftermath of the civil war. These writers are vocal critics of what they perceive to be Arab culture’s tendency to forgo individual freedom and political democracy for the purpose of armed resistance, anti-imperialism, provincialism, and nationalism.

Youssef Bazzi, “A Short History of the Relationship Between Lebanese Arts Production and Foreign Funding,” Babelmed, July 18, 2007 →.

Nicola Pratt, “Human Rights NGOs and the ‘Foreign Funding Debate’ in Egypt,” in Human Rights in the Arab World, ed. Anthony Tirado-Chase and Amr Hamzawy (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 114–26.

Pratt, “Human Rights NGOs,” 114.

For a summative analysis of the “foreign funding debate” with particular regard to Egyptian women’s rights and the NGOs where these debates are most hotly contested, see Nadje Al-Ali, Secularism, Gender and the State in the Middle East: The Egyptian Women’s Movement (Cambrige University Press, 2000).

Pratt, “Human Rights NGOs,” 114.

Ibrahim Abu-Rabi‘, Contemporary Arab Thought: Studies in Post-1967 Arab Intellectual History (Pluto, 2004), 134.

Ghassan Salamé, The Foundations of the Arab State: Nation, State, and Integration in the Arab World, vol. 1 (Routledge, 1987), 52.

A good example of how this binary is drawn on historically is found in Kamal Boullata, Palestinean Art: From 1850 to the Present (Saqi, 2006), 126, in which he describes two intellectual currents among literary forms and magazines reflected in the visual arts. The first current called for an engaged literature as popularized in the immediate post–World War II era by French existentialists such as Jean Paul Sartre. The second emanates from artists whose figurative language perpetuated a narrative pictorial art that seemed to echo the metaphorical imagery popularized by the poetry introduced in the pan-Arabist Al-Adab, founded and edited by the writer and literary critical Suhail Idriss. The poets associated with Shi’r, on the other hand, valorized the more abstract and experimental artists.

See Al-muthaqaff al-arabi: humumuh wa ata’ouh (The Arab intellectual: Challenges and concerns), ed. Anis Sayegh (Markez Dirasat al-Wihdah al-A‘rabiyah, 2001) for an understanding of the concerns and thinking of this generation. See also Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab, Contemporary Arab Thought: Cultural Critique in Comparative Practice (Columbia University Press, 2009).

Lara Deeb, An Enchanted Modern: Gender and Public Piety in Shi’i Lebanon (Princeton University Press, 2006), 13. For a thorough and polemical take on cosmopolitanism as ideological warfare, see Timothy Brennan, At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now (Harvard University Press, 1997). On how conceptions of cosmopolitanism and nationalism shape identity and protest, see Rahul Rao, Third World Portest: Between Home and the World (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Discussion with the author, April 12, 2015.

Daniel Drennan ElAwar, “A Black Panther in Beirut,” Counterpunch, January 13, 2020.

For more on this debate, see Mohammed (1989) and Sabry (2010: 29). For the preoccupation with assala (authenticity) in artistic production today, see especially Winegar (2006: chaps. 1–3). Through a critique of three major pan-Arab conferences that took place in the Arab world after 1967 as part of Arab intellectuals’ introspective turn, Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab’s Contemporary Arab Thought provides a comprehensive take on the place of authenticity and tradition in the post-1967 intellectual scene, arguing that these notions are often de-historicized while simultaneously idealized by cultural elites.

In Trials of Arab Modernity, literary scholar Tarek El-Ariss makes similar suppositions about the experience of encountering modernity as an experience rather than as a representation (of an event). He reframes Arab modernity as a somatic condition shaped through “accidents and events (adth) emerging in between Europe and the Arab World” (El-Ariss 2013: 3).

Samah Idriss, founding editor of Al-Adab, a Lebanese Arabic language arts and culture journal, and son of the late literary giant Suhail Idriss, who was deeply involved in confronting Hiwar’s role in the cultural Cold War, cynically wondered in conversation with me how it was that Tawfik Sayigh’s journal suffered the fate it did, while today an entire industry is built around the politics of Western funding for culture and the arts “with hardly any questions asked by the generation building it.”

A comprehensive report on cultural policies in the Arab world shows how the language of development, civil society, and democratization is interwoven with arguments about the politics of arts production in the region (Al Khatib et al. 2010).

Zeina Maasri, Off the Wall: Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War (Tauris, 2020,) 94.

Arndt 2005: xviii

Iriye 1991: 215.

Kim 2017. Soft power describes the ability of a political body, such as a state or its civil society, to indirectly influence, through trust and mutual understanding, the behaviors or interests of other political bodies through ideological means of persuasion rather than coercion. For more, see Nye (2004).

An interesting read in this regard is Tim Rivera’s (2015) report on cultural relations or cultural diplomacy in reference to the British Council. See also Bátora (2005); Melissen (2005); and Cull (2009).

Melissen 2017.

Kim 2017: 294

Williams 1961: 57–70. In this reading, Williams tries to break down the analysis of culture into three terms; ideal, documentary, and social. Ideal refers to lives, works, and values; documentary is the body of the intellectual work (i.e., the actual evidence of the culture); and social is the description of a particular way of life. The social element could refer to traditions or language. Williams also ascertains that the dependent relationship between dominant, residual (as in remnants of the traditional), and emergent cultural forces is an ongoing practice of exchange, confrontation, and assimilation on all fronts within the hegemonic sphere. These three elements invariably and selectively co-opt each other (Williams 1977: 110).

Interview with the author, May 2, 2008, Beirut.

Interview with the author.

Daccache 2006: 21

Strategic Communications Division, EU 2016.

(Bloembergen 2006)

The concept of power in public diplomacy has been explored in Rasmussen’s discursive influence model of normative power (2009). These normative frameworks have been criticized in Pamment (2011). See Sylvester (2009) for an alternative view that utilizes feminist and poststructuralist approaches to account for the role of culture in international politics. For an excellent analysis of Mitchell’s piece, see the introduction of his republished chapter in Preziosi (2009).

For more on the world exhibitions, see both Allwood (1977) and Benedict (1991). See also Çelik (1992).

To see how the power relations inherent to cultural diplomacy are elided by framing the practice as an enjoyable dimension of public diplomacy that values free cultural expression, see Schneider (2004).

In the aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001, a plethora of articles, reports, and op-ed pieces appeared that gave attention to how the US and its values, culture, and policies are perceived abroad and how it can improve those perceptions. Among the recommendations were calls for increased efforts in the area of cultural diplomacy. Ironically, the renewed interest in cultural diplomacy comes at a time when the country’s resources and infrastructure are at their lowest levels. Since 1993, budgets have fallen by nearly 30 percent, staff has been cut by about 30 percent overseas and 20 percent in the US, and dozens of cultural centers, libraries, and branch posts have been closed. See “Arts and Minds: Cultural Diplomacy amid Global Tensions” (presentation, Columbia University, New York, NY, April 14–15, 2003).

Cynthia Schneider, “Culture Communicates: US Diplomacy that Works,” Diplomacy, no. 94 (September 2004) →.

Schneider, “Culture Communicates” details these changes in funding focus.

Category

Subject

This essay is an edited excerpt from The Politics of Art: Dissent and Cultural Diplomacy in Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan (Stanford University Press, 2021). Copyright the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.