If modern Eurocentric history remains dominant in contemporary art discourse, what happens to the available theory and criticism of contemporary African art? At present, accounts of contemporary African art appear in a growing collection of critical, curatorial, and artist writing. How do these narratives, opinions, and polemics inform the critical review of African art practices? Further, in a pervasively Eurocentric setting, an atmosphere in which Western critics look at African art as illegitimate, how can a theory of South African art encourage an alternative reception of contemporary African art practices in general?

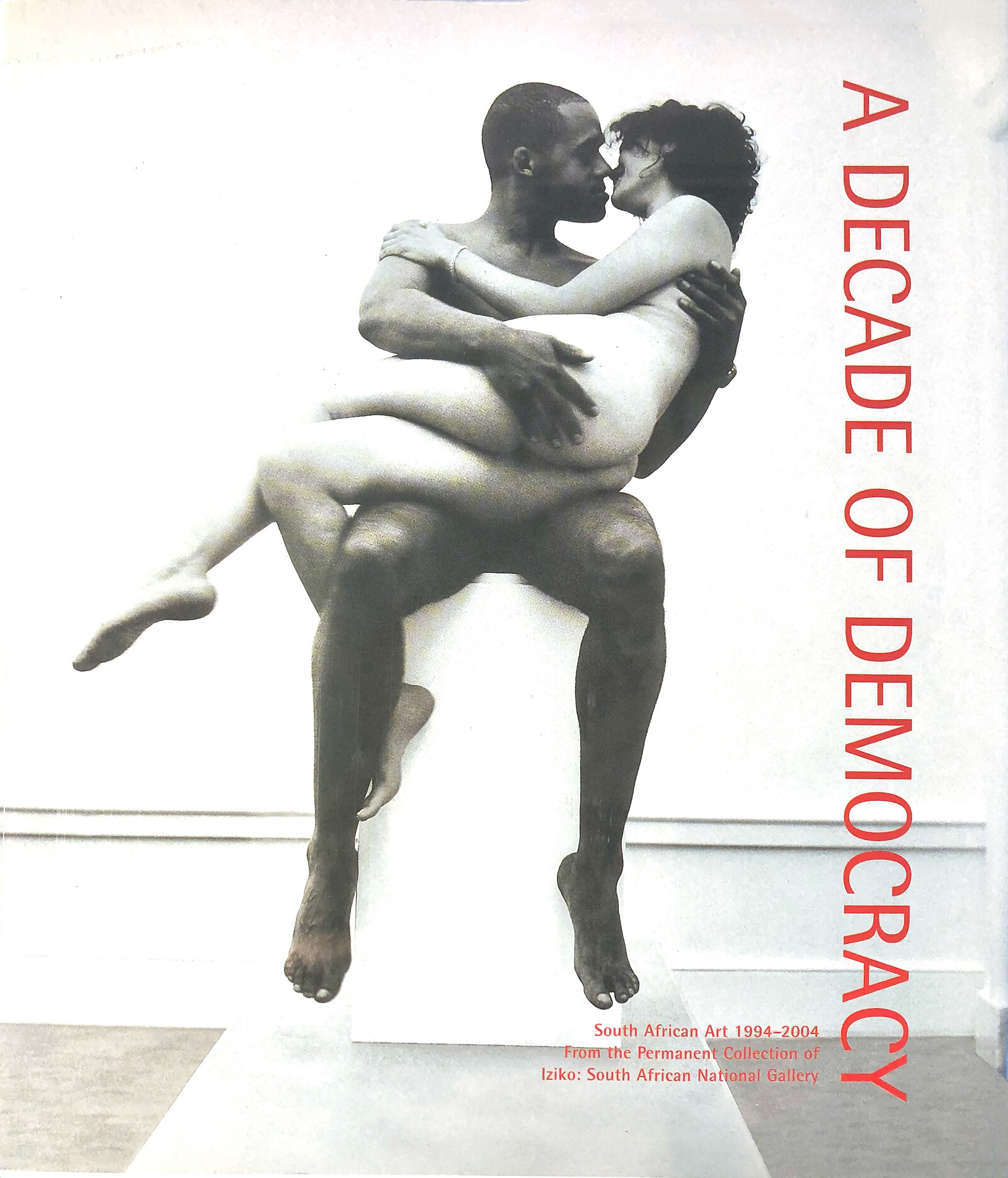

In 2005, critic Ashraf Jamal began developing the theory of art in question. That year he wrote “The Bearable Lightness of Tracey Rose’s The Kiss” for the exhibition catalog accompanying “A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994–2004.”1 This exhibition attempted to demonstrate the political and historical consciousness of South African artists in the years following the country’s first democratic election in 1994. Jamal’s catalog essay, examining artist Tracey Rose and novelist J. M. Coetzee (both South African), shows the formulation of a theory2 that claims a national category for art while advancing a postcolonial theory of art. In the latter, Jamal mirrors earlier attempts by contemporary philosophers Kwame Anthony Appiah, Homi Bhabha, and Valentin Yves Mudimbe.3 The analytic philosophical approaches of Jamal’s theory of art, and similar approaches in Coetzee’s theory of literature, ultimately establish artistic thought as a realm of liberation.

1. The Inheritance of Anger and Violence in J. M. Coetzee’s Theory of Literature

In his 1987 Jerusalem Prize Lecture, Coetzee outlines a theory of literature rooted in political philosophy and psychology.4 His theory concerns the politics of race in South Africa, and argues through a psychology of the individual drawn from his novels Dusklands (1974) and Waiting for the Barbarians (1980). The lecture formulates its theory in three ways: (1) through the lens of what Coetzee terms “symbolic” law, considering the racial segregation law forbidding interracial sexual relations (the Immortality Act, also known as the Sexual Offenders Act, 1957); (2) through a psychological approach, by considering the “pathological attachments of anger and violence”; (3) through the notion of caste, by considering the white population as “master-caste.”5 It also reads as a denouncement of racial segregation in 1980s South Africa following the civil warfare that erupted in that decade, not only in South Africa but across Africa. During the eighties, what Mahmood Mamdani calls “senseless violence” was rampant in countries like Uganda, where similar decolonization and power struggles were taking place.

The political questions Coetzee lays out to guide his theory of literature include: (1) does “anger and violence” shape a world, and one’s imagination of it?; and (2) can white people resign from their role as the master-caste? He also explores (3) the freedom and liberation of the master-caste; (4) the “crudity of life in South Africa”; (5) the perception of the nation as “irresistible” and “unlovable”; (6) and the symbolic law. How might these questions lay a foundation for Jamal’s theory of art?

We learn from Jamal that Coetzee’s theory of literature is yet unfulfilled, revealing the daunting challenge of creating a literature that reflects the task of quitting “a world of pathological attachments.”6 Waiting for the Barbarians depicts a white magistrate witnessing “the Empire’s cruel and unjust treatment of prisoners of war,” while the earlier novel Dusklands explores a white colonial officer’s deteriorating psychology. Both novels recall the mental corrosion of Mr. Kurtz, a Victorian seafaring explorer in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). In his lecture, Coetzee plainly states that “everyone born with a white skin is born into the caste,” and then claims it is impossible to resign from the master-caste, except perhaps symbolically.7 Coetzee’s claim that the condition of the master-caste is hereditary whiteness diverges from how caste is understood in India, for example, where it is not “white skin” alone that determines one’s caste, but rather various social hierarchies according to Hindu sacred texts. This early attempt at defining whiteness in literary theory is also an essentialist perspective that reinforces the stereotypical notion of those born with privilege. Even as he aims to rescue South Africa from its pathological attachment, Coetzee centers whiteness, with its foundation in imperialism and colonialism.

“In a society of masters and slaves, no one is free,” he asserts. “For centuries South Africa was a society of masters and serfs; now it is a land where the serfs are in open rebellion and the masters are in disarray.”8 Thus, the nation of South Africa becomes synonymous with land. This resonates with twentieth-century land laws. Nonwhite people are synonymous with serfs and slaves. This statement also reveals the essentialism that informs Coetzee’s racial history. Likewise, the definition of whiteness as “master-caste” implies a lineage of “white masters” throughout South African history.

Coetzee asks whether the master-caste is free and liberated.9 He sets up parallel dialectics: colonialist and colonized; barbarians and civilized; masters and slaves. If we are to follow such strict boundaries of thought, and categorization, it appears rather obvious to me that freedom and liberation would be granted to one subject and not the other. Coetzee’s notion of a South Africa as “irresistible as it is unlovable” presents another dialectic that foregrounds both the threat of violence and the crisis of morality.10 That is, Coetzee sees South Africa as unlovable for its moral bankruptcy of caste, and irresistible to the colonizing mechanism, particularly in regard to natural resources. This dialectic is mirrored in law: the notion of the racial segregation law as “symbolic” suggests that the law is not only constitutional—in other words, enforced through state violence—but also moral. Coetzee thus rearticulates the law in terms of a set of parallel dialectics: individual and collective; moral and political; actual and symbolic.

Jamal throws down the gauntlet on this historiography and its dialectics. He opposes Coetzee’s characterization of South African history through the lens of barbarism. Coetzee’s account of barbarism relies on a dialectic of barbarism and civilization; and further, when the novelist speaks of agency and subjectivity—as in the agency of questioning the master-caste, or in the subjectivity of white colonial characters in his novels—he does so in a way that centers whiteness as the benchmark of a history of the nation. Jamal’s task is to push back against this idea that “agency” is only possessed by white subjects. He rails against the idea of “barbarism” writ large in South African history.

By countering that “South Africa is not irresistible and unlovable,” Jamal directly rewrites—and to an extent negates—Coetzee’s statement, which Jamal calls as “efficacious as it is disingenuous.”11 The critic’s revision of the statement (“I propose that South Africa is resistible and lovable”) perhaps functions as affirmative sabotage. Gayatri Chakravarty Spivak uses that term as a “gloss on the usual meaning of sabotage: the deliberate ruining of the master’s machine from the inside.” She explains that affirmative sabotage is instead “the idea of entering the discourse that you are criticizing fully, so that you can turn it around from the inside.”12 Judging by the affirmative attitude that Jamal borrows from Coetzee’s lecture, I view him attempting to fully inhabit Coetzee’s theory of literature so that he can turn its language around on itself. Jamal takes Coetzee’s theme of the pathological, which the novelist uses to examine the psychological deterioration of white subjects, and redirects it towards “rethink[ing] the pathology of our history.”13

Jamal appropriates and repurposes Coetzee’s language, particularly the latter’s formulation about “the crudity of life in South Africa … its callousness, and its brutalities.” As Jamal writes:

When art is not depressive or gauchely hopeful, it enables the lightness that frees South Africa from the brute template that has disfigured it. When such art happens we are invited into a speculative and wondrously improbable arena where fascination no longer revolts, where the perversity of one’s birth is no longer the birth of perversity per se, where givens groan under the weight of their absurdity, and one suddenly alights upon a place that, at best, can be described as the place of the imagination.14

Here Jamal rearticulates Coetzee’s statement about South Africa’s crudeness and brutality as “the brute template that has disfigured it,” juxtaposing this with art’s political role in “freeing South Africa.” I view this gesture as mirroring Coetzee’s characterization of South African law as having a double function: both moral and political, individual and collective. Jamal echoes this Kantian articulation of the law, and sketches out a theory of art that is neither “hopeful” nor “depressive.” Instead, echoing Milan Kundera, Jamal emphasizes the artist’s ability to create “lightness.” His theory centers on this notion of art as a neutralizing force, one that can contribute to freeing South Africa.15 By linking liberation and art, Jamal promotes a Kantian perspective, which, according to scholar Gabriella Basterra, entails that “freedom manifests itself through moral law.” As Basterra argues, “that freedom is actual means it motivates the subject to act.”16 That act is the creation of “lightness.” This repositions art under the auspices of moral law, as a countering force to the callousness and brutality that has brought about what Coetzee calls “a world of pathological attachments.”

Jamal extends this psychoanalytic language of Coetzee’s when he discusses Tracey Rose’s video TKO (2000):

Irrespective of her trickery, her mockery, her fraught eye, her terribly self-reflexive carnage, [Tracey Rose] at no point allows herself to be beguiled by the pathological. Illness for her is not an inheritance or a moral duty but a plague she roots out with a vengeance. The video work TKO reveals the artist beating the shit out of a punching bag. In grainy black and white, the images quaver, nauseously revolve, accompanied by the accelerated panting of the artist.17

It may sound aggressive to highlight “the artist beating the shit out of a punching bag,” but it is the central action of the work, and a welcome aggression. Aggressiveness functions to “root out” the deeply embedded problems of erasure and misnaming in universalist art history. The punching bag, a visual image, is part of the video TKO, the art object. Its presence is authentic to the narrative of freedom, and as in great epics and historical novels, catharsis is central to how history is told. The act of punching the bag is a mirror of “lightness” and catharsis. In Jamal’s theory of art, it is a neutralizing force that has implications for national liberation. However, the punching itself is also an abstraction, and its catharsis is psychoanalytical. The notion of a theory as a neutralizing force is formulated against the backdrop of analytic philosophy and its idea of “truth”; modern philosophy and its grand narratives of freedom, modernity, empire, and violence, as well as the general logic of reason.

2. Freedom as Refusal in Ashraf Jamal’s Theory of Art

How might we pivot from Coetzee’s considerations of the 1957 Immorality Act to Jamal’s theory of post-1994 South African art? How does Coetzee’s unfreedom pivot to Jamal’s aim for art to “free South Africa”? The recognition of the dual character of law in Coetzee’s lecture alerts us to the individual and the collective, the symbolic and the actual. It also highlights the complexity of Kant’s thinking regarding freedom and its existence. Is freedom real? Does it exist? And if it does, how do we prove its existence? For Kant, moral law is proof of freedom’s existence. Basterra argues that “freedom exceeds reason’s ability to conceptualize. We can only define freedom negatively as an empty space beyond what can be thought.”18 This is further explained in relation to subjectivity and the intelligible. “Freedom is in the subject, even though the subject has no access to freedom. A member of unwitting causality, the subject is also the unwitting bearer of freedom, and thus is related to the intelligible.”19 These definitions of freedom enable a wrestling with subjectivity. How then to situate these definitions in the examination of Jamal’s claim of art’s role in “freeing South Africa”?

The Kantian idea of moral law is one in which the subject has agency and is intelligible. But this view is challenged by the “symbolic” laws that define whiteness and racial segregation. Coetzee’s lecture alerts us to the symbolic and actual laws as they operate in South Africa. I suspect that the novelist defines the law of segregation as symbolic because he pursues a Kantian understanding of the law as moral law, and thus believes in the sensible and intelligible. Coetzee’s lecture is attentive to the ways in which white South Africans have unconsciously extended the actual law of segregation—for example, in their “denial of an unacknowledged desire to embrace Africa, embrace the body of Africa; and the fear of being embraced in return by Africa.”20

This characterization departs from the 1957 law against interracial sexual relations, and therefore, “embracing Africa” reifies this law into symbolism. Is the question about “embracing Africa”—that is, seeing it objectively from outside of white subjectivity—or is the question about cohabitation with African subjects? The latter would mean banning racial segregation, and ultimately the transformation of legal and everyday practices of humaneness in South Africa. That is, if we trust Kant’s suggestion that subjectivity is a phenomenon of nature.21 Jamal departs from Coetzee here to revise the latter’s lecture and its theory of literature in order to formulate a theory of art.

For Coetzee, “freedom” is accessed through a transformation of subjectivity (the disavowal of pathological attachment) and through racial integration (the embrace of Africa). Ultimately, this creates tense social relations, which lead to what Chantal Mouffe might call political antagonism. Yet the weight of the transformation of subjectivity in Coetzee’s Dusklands and Waiting for the Barbarians is placed on the psychological, tending towards the Nietzschean “physiological thought.” To “quit a world of pathological attachments,” Coetzee challenges “abstract forces of anger and violence.”22 The novelist analyzes pathologies of violence and anger in South Africa through the lens of whiteness. As part of his methodology, Coetzee uses free association, aiming to root out the anger and violence of “historical” whiteness and its anxieties. He finds an answer to the problem of pathology in the space of imagination, citing Cervantes’s Don Quixote. Coetzee relays the pivotal beginning of Quixote’s quest: “He leaves behind hot, dusty, tedious La Mancha and enters the realm of faery by what amounts to a willed act of the imagination.”23 Back in Coetzee’s present, Freudian analysis enables the transformation of the subject at hand—the white South African subject—in order to “embrace Africa” and ultimately destroy Apartheid in South Africa. Coetzee’s notion of freedom, following Kant, rests within reason. If the white South African subject is to annihilate their unfreedom, it can only take place within the intelligible, the space of reason, and, following Cervantes, the space of imagination.

Coetzee’s Dusklands achieves this transformation through analyzing the psychological state of Jacobus Coetzee (the novelist’s ancestor), and his violence against the Nama, an African society. Though members of the Nama care for the traveling protagonist while he battles illness, he later returns to them, vengeful, on a violent campaign that shows his inhumanity. In a 1984 essay, Coetzee describes the events of eighteenth-century European travel narratives to Namaqualand (Namibia and South Africa) that inspired the novel as “the fortunes of the Hottentots in a history written not by them but for them, from above, by travelers and missionaries, not excluding my remote ancestor Jacobus Coetzee, floruit 1760.”24 Psychoanalytic scholar Steven Groarke writes of these colonial travel narratives that “Jacobus Coetzee’s narrative itself is an overdetermined expression of self-consciousness, a racist myth of history, and a theological justification of genocidal violence. The violence of frontier terror is pivotal.”25 Jamal advances a theory of art that destabilizes Coetzee’s psychoanalysis by challenging the myth of inheritance in his theory of literature. Jamal does this through: (1) denouncing the myth of inheritance of pathological illness; and (2) developing a theory of art rooted in a neutralizing force, with implications for national liberation. As we have learned from Freud, myths and their propagation are the basis of nationalism. If Jamal refuses myth in favor of play, it is nevertheless a playfulness that serves the nation.

By rejecting the inheritance of pathological illness (such as that of Jacobus Coetzee), Jamal refuses the myth of South African art as conditioned only by what he refers to as a “tidy pathological matrix.”26 Jamal refuses to theorize art along the racial lines of a “closed hereditary caste” established in Coetzee’s lecture. Importantly, this refusal signals a redefining of Coetzee’s universalism. Jamal’s theory of art is inclusive of all races in South Africa, and carries the weight of the sensible. Rejecting inheritance is the refusal of the white colonial foundational myths of the modern South African state. This can certainly be understood as an act of decolonization. Jamal’s theory of art, in other words, includes a psychology of decolonization that destabilizes the myths of modern and contemporary art as an exclusively white enterprise. Coetzee’s sharp clarification of the anxieties of “historical” whiteness is South Africa, and his articulation of racial history, is what allows Jamal to challenge the inheritance of whiteness within art.

Jamal’s decolonizing vision of art is dependent on a two-fold resistance to Coetzee’s racialized myth: (1) political resistance against a hereditary caste; and (2) psychological resistance against inheriting illness. Jamal’s discernment of playfulness, humor, and lightness in Tracey Rose’s artwork enables his theory to depart from the “moral law” that shapes subjecthood in Coetzee’s lecture. Instead, he argues for art as a neutralizing force that “roots out” all pathology. Art is a psychoanalytical tool in a process of decolonization. This reveals a political motive behind his case for art as an aggressive force. Based on his citations of Steve Biko (I Write What I Like, 1977) and Ben Okri (Steve Biko Memorial Lecture, 2012), this aggressive turn in his theory, and its hostility towards “pathological attachments” and psychosis, can be understood as Jamal’s formulation of a modern national consciousness, following Steve Biko’s theory of Black Consciousness. It is important to note that the universal in Jamal’s modern national subject is not identical to Coetzee’s racial universalism. As such, Jamal’s theory should not be confused with Pan-Africanism.

Some of these issues are further clarified in Jamal’s 2015 article “Long Overdue,” published in Art Africa magazine. In the article, Jamal’s ambivalence towards Africa is keenly felt. He rejects Coetzee’s call to embrace Africa, and his doubt registers as pessimism. This pessimism can be seen to be in dialogue with philosopher Achille Mbembe, whose theories on postcolonial Africa have influenced the theorization of afro-pessimism in the United States. In particular, Jamal rejects the blind optimism of “embracing Africa” through the capitalist system of art fairs and art auctions, describing it as the new “scramble for Africa.” This, too, confirms the Jamal’s interest in decolonization.

The title “Long Overdue” is a reference to Steve Biko’s monumental book of Black Consciousness, I Write What I Like. Jamal extends Biko’s book, as well as novelist Ben Okri’s Steve Biko Memorial Lecture from 2012, in order to diversify consciousness for a theory of national art. Biko provides a postcolonial humanism, while Okri provides a theory of literature in naming “three Africas,” one of which isn’t readily visible. These are, according to Okri, “the one we see everyday; the one they write about; and the real magical Africa that we don’t see unfolding through all the difficulties of our time, like a quiet miracle.”27 Jamal’s theory extends these sources of pessimism, postcolonial humanism, and Ben Okri’s “invisible” Africa to a theory of South African art.

While reconciling these diverse interests, Jamal ultimately centers individuality in his theory. Jamal pursues Coetzee’s thoughts on the meeting of artistic and analytical knowledge in the subject, which can be seen as bringing together aesthetic experience and judgement. In Critique of Pure Reason, Kant writes that “without the sensuous faculty, no object would be given to us.” And thus, logic necessarily intersects with sensibility and is also “sensuous cognition.” This idea of the sensible is what enables Jamal to designate the artist as a thinking individual. Thus, positioning the artist as a thinker transforms South African art by centering freedom within the subject’s sensuous cognition. Here, the possibilities of freedom manifest in artistic investigation.

Jamal is interested in the “political” in way that doesn’t center whiteness as a universal, but rather aims at employing “aggressiveness” in the struggle against historical anxieties. The political motive of freeing South Africa is what lies behind, for example, Jamal’s hostility towards “pathological attachments.” In the waltz between lightness and aggressiveness, we witness the range of possibilities for the artist’s thought and action. Sigmund Freud wrote about the aggressive drive in Civilization and its Discontents (1930), where he held that without culture, people were driven to extremes by a certain aggressiveness. The mixture of aggressiveness and applied logic in Jamal’s theory of art means that artists are thinking and acting politically.

The notion of “lightness” in Jamal’s theory comes from Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984). In an interview, Kundera foregrounds lightness and playfulness when he mentions the “specificity of the novelistic essay (in other words, instead of claiming to convey some apodictic message, remaining hypothetical, playful, or ironic).”28 For me, these light-hearted aspects can only exist side by side with the aggressive drive we witness in Freud. This waltz between lightness and aggressiveness introduces a theoretical framework in which to situate the strategic thought of calling out the madness of historical violence, while still presenting irony and lighthearted playfulness. These aspects of lightness, aggressiveness, applied logic, and sensuous cognition further define Jamal’s theory of art.

Since aggressiveness is established in dialogue with Tracey Rose’s video TKO, Jamal locates the punching bag within a psychology of aggression. The act of punching the bag in the video is aggressive and violent. Jamal justifies this kind of violence as a neutral rooting out pathological illness with a vengeance. It is a rational counteracting force to historical violence, with the aim of eradicating madness. The notion of a force that counteracts historical violence recalls the theme of aggressiveness in political philosophy, notably in Hannah Arendt (On Violence, 1968), and Chantal Mouffe (The Return of the Political, 1993).

Central to Jamal’s rebuttal of Coetzee’s account of whiteness as a master-caste is a refusal to accept or tolerate the inheritance of illness and pathology. Jamal presents a postcolonial theory of art that denounces pathological inheritance and historical violence (e.g., laws of segregation), while embracing Okri’s magical Africa and Biko’s Black Consciousness. While Jamal’s theory advocates a national art that is ambivalent towards Pan-Africanism, his rejection of a universal master-caste narrative is what I identify here as his politics. I view this rejection and its hostility as aligned with Mouffe’s notion of the political. Mouffe takes issue with a notion of politics that is “rationalist, universalist and individualist,” traits which she says have come to mark democracy.29 She also calls out the “incapacity of liberal thought to grasp … the irreducible character of antagonism” in politics.30 Fiercely defending the idea that political action takes place both outside and inside institutions, Mouffe’s calls attention to modern political theory’s blindness towards antagonism.

By praising aggressiveness, Jamal’s theory of art comes very close to the theory articulated by Frantz Fanon in the chapter “On Violence” from his The Wretched of the Earth. This means that Jamal can be subject to the same criticisms that were directed at Fanon. Hannah Arendt stands out as one of Fanon’s most articulate critics. She was strongly opposed to Fanon’s conception of political violence as chiefly justified through creativity. She argued that in his writings on Algeria, “Fanon concludes his praise of violence by remarking that in this kind of struggle ‘the people realize that life is an unending contest,’ that violence is an element of life.”31 While this sounds plausible, Arendt goes on to challenge Fanon’s equation of violence with creativity, quoting Fanon’s formulation of “creative madness.”32 While Jamal’s theory of art stands against racial violence and the historical anxieties of whiteness as pathological illness, it is still a theory that deploys aggressiveness in the context of art and creativity. If this gesture is balanced by reason and applied logic, these analytical aspects paired with Tracey Rose’s thinking might rescue Jamal’s theory from the “creative madness” that Arendt opposes.

3. Art History and Difference in Tracey Rose’s Artistic Vocabulary

Around the turn of this century, Tracey Rose made a number of photographic artworks modeled after Auguste Rodin sculptures, specifically Authenticity 1 (1996) and The Kiss (2001). The latter was made during Rose’s artist residency at Iziko: South African National Gallery. As curator Emma Bedford writes, in The Kiss “the canons of conventional art history are imploded by substituting the marble-white bodies, those epitomes of aesthetic perfection, with bodies that assert their difference through a range of skin tones.”33 This implosion of art history in Rose’s perambulations around Rodin inspired Jamal to argue for an art that confronts national history writ large. The Kiss portrays Rose and Christian Haye, her dealer, in an intimate embrace on a plinth, echoing the Rodin sculpture of the same name. The picture was staged inside the Iziko, highlighting the European classical model that is at the core of the museum collection, as evidenced by, among other things, the gallery’s permanent hanging of equestrian paintings from the collection of Abe Bailey, the diamond tycoon and politician with ties to the likes of Cecil Rhodes. Juxtaposing the museum’s plinth and white walls with the colored bodies embracing in the frame, Rose’s The Kiss asserts historical and racial difference in its mode of parody. In subsequent showings, the work was viewed as a direct critique of “a unified image of post-apartheid society bathing in its own glory.”34 This view, emphasizing the dismantling of neat and tidy images of South Africa, confirms Rose’s distance from what Mouffe calls “rationalist, universalist and individualist” politics. The artist’s foregrounding of difference and “multiplicity” reveals a radical politics that differs from the politics of both Coetzee and Jamal, who both make universalist claims (about caste and national art, respectively).

As art historian Kellie Jones argues, Rose’s practice centers both writing and thinking.35 What are the operations behind Rose’s art-as-thinking? The conceptualism in her practice is evident in its references and citations, including of artists such as Rodin. Another aspect of Rose’s art-as-thinking concerns the various strategies she uses to highlight difference. Rose’s artworks adopt multiple subject positions, which has the effect of collapsing universalist modes of thought—like those found in art history. In works such as Ciao Bella (2001), Rose performs as different female characters, including the nineteenth-century Xhosa woman Saartjie Baartman, taken from the Cape Coast to Europe to act as a living spectacle, and Mami, a stern Catholic school mistress. Like the work of feminist theorist Audre Lorde, who analyzed class and gender-identity differences among black women, Rose’s work shatters assumptions about subjectivity and knowledge.

While Rose’s art challenges neat art-historical canons and disrupts assumptions about black women in particular, we would be remiss to consider Rose a scientific thinker performing art-historical analysis or revision. This notion obscures the artist’s unique approach, which offers alternatives to thinking through subjectivity, knowledge, and narrative. Rose tackles these philosophical topics using creative, fictional, playful, and performative strategies. In her performance lecture The Can’t Show, delivered at the Brooklyn Museum in the context of the exhibition “Global Feminisms” (2007), Rose, dressed as the Catholic schoolmistress Mami, told the story of women in conceptual art, mentioning artists like Adrian Piper and Barbara Kruger. The performance employed the puppet ventriloquism of European theater. While audiences could walk away from the performance with art-historical knowledge, the story Rose presented was far from scientific truth. Treating the performance as truth would obscure the artist’s creative strategy to present this knowledge to the audience through fiction.

As seen in works like Ciao Bella and The Kiss, there is a clear emphasis on difference in Rose’s practice. This tendency diverges significantly from the universal claims about national art in Jamal’s theory of art, and about caste in Coetzee’s theory of literature. Rose is unapologetic about the engagement with difference in her art-as-thinking, which foregrounds racialized, sexualized, and gendered subjects. In Chantal Mouffe’s terms, Rose is engaging in a radical antagonistic politics that differs from the Kantian rationalism and universalism that informs much historical and aesthetic writing.

Still, through her citational and comparative practices, Rose inspires Jamal’s theory of art, one in which artists think and act politically while confronting historical violence. Jamal’s theory aims at disavowing the inheritance of pathological illness and historical violence, opposing Coetzee’s notion of caste in favor of diversified consciousness. Jamal challenges easy assumptions about South African artists and their work in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In Jamal’s view, the artistic subject acts politically to “free South Africa.” In a Kantian vein, Jamal’s theory centers individuality and the rationalism of the artist-thinker. This emphasis on the artist-thinker foregrounds art as a domain of liberation.

Ashraf Jamal, “The Bearable Lightness of Tracey Rose’s The Kiss,” in A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994–2004: From the Permanent Collection of Iziko: South African National Gallery, ed. Emma Bedford (Double Storey Books, 2005), 102–9. The essay focuses on Tracey Rose’s video works TKO (2000) and Ciao Bella (2001), and her photographic print The Kiss (2001).

The theory has taken further shape in Jamal’s writings in art magazines, as well as in the introduction to his book In the World: Essays on Contemporary South African Art (Skira, 2017), 11–14.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, “Is the Post- in Postmodernism the Post- in Postcolonial?” Critical Inquiry 17, no. 2 (1991); Homi Bhabha, “Beyond the Pale: Art in the Age of Multicultural Translation,” in Cultural Diversity in the Arts: Art, Art Policies and the Facelift of Europe, ed. Ria Lavrijsen (Royal Tropical Institute, 1993); Valentin Yves Mudimbe, The Idea of Africa (Indiana University Press, 1994).

J. M. Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech (1987),” in Doubling the Point: Essays and Interviews, ed. David Attwell (Harvard University Press, 1992), 96–101.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize.”

“How we long to quit a world of pathological attachments, and abstract forces of anger and violence, and take up residence in a world where a living play of feelings and ideas is possible, a world where we truly have an occupation.” Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 98.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 96.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 96.

“The unfreedom of the master-caste.” Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 96.

“The crudity of life in South Africa, the naked force of its appeals, not only at the physical level but at the moral level too, its callousness and its brutalities, its hungers and its rages, its greed and its lies, make it as irresistible as it is unlovable.” Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 99. Italics added.

“South Africa is not irresistible and unlovable as Coetzee has claimed, a claim as efficacious as it is disingenuous; rather, the view I would propose is that South Africa is resistible and lovable. By this I mean that one survives the barbarism of one’s history irrespective of the template that has normalised one’s illness. Coetzee knows this, as does any thinker who has delved into the pain that has been said to define what it means to be South Africa.” Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Gayatri Spivak, “When Law is Not Justice,” New York Times, July 13, 2016.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 108.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Gabriela Basterra, The Subject of Freedom: Kant, Lévinas (Fordham University Press, 2015), 9.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Basterra, The Subject of Freedom, 6.

Basterra, The Subject of Freedom, 6.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 97.

Basterra, The Subject of Freedom, 7.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 98.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 98.

Quoted in Steven Groarke, “The Disgraced Life in J. M. Coetzee’s Dusklands,” American Imago 75, no. 1 (2018).

Groarke, “The Disgraced Life,” 35.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 103.

Ben Okri, Thirteenth Steve Biko Annual Memorial Lecture, University of Cape Town, September 12, 2012 →.

Milan Kundera, “The Art of Fiction,” Paris Review, no. 92 (Summer 1984).

“The evasion of the political could, I believe, jeopardize the hard-won conquests of the democratic revolution, which is why, in the essays included in this volume, I take issue with the conception of politics that informs a great deal of democratic thinking today. This conception can be characterized as rationalist, universalist and individualist. I argue that its main shortcoming is that it cannot but remain blind to the specificity of the political in its dimension of conflict/decision, and that it cannot perceive the constitutive role of antagonism in social life.” Chantal Mouffe, introduction to The Return of the Political (Verso, 1993), 2.

Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 4.

Hannah Arendt, On Violence (Harcourt Brace, 1970), 69.

Arendt, On Violence, 75.

Emma Bedford, introduction to fresh: Tracey Rose (Iziko: South Africa National Gallery, 2003), 5.

Kim Gurney, “Ten Years On,” Arthrob, no. 1 (May 2004).

Kellie Jones, “Tracey Rose: Post-apartheid Playground,” in fresh: Tracey Rose.