Grace Dillon is an Anishinaabe cultural critic, professor in Indigenous Nations Studies at Portland State University, and a key figure in contemporary conversations about Indigenous Futurisms. Anchored in analyses of science fiction, her work spans literary sources, film, and popular culture. Her edited anthology Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (2012) has become an invaluable guide to the growing field of Indigenous Futurisms and its many ramifications in studies and debates about race, gender, geography, science, and the notion of temporality itself. In this sense, Indigenous Futurisms—in the plural, as Dillon reminds us in this interview—encompass Indigenous perspectives on science fiction, speculative storytelling, and world-building through literary, cinematic, and other artistic forms, emphasizing both the colonial role of science and technology and its decolonial uses in affirming Indigenous sovereignty and creativity.

As a filmmaker, artist, and writer who has done extensive work in Brazil, I found myself confronted with the questions of who defines futures, when is the future, and what is futurity itself. This led me to consider the politics behind science fiction—its ideologies and world-building powers. In particular, my work with Indigenous actress and artist Zahy Guajajara, starting with my fiction film Exterminator Seed (2017), and my conversations with anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, among others, have led me to inquire about the cosmopolitical encounters and mis-encounters between my native Portugal and Brazil—that is, between “parallel futures.” Although the notion of futurity itself is part and parcel of normative processes, the reality is that many futures survive and thrive in the present. In this respect, Dillon’s work has been particularly important for me. Hers is a voice that helps us navigate the depressing reality of colonial legacies but also the affirmative, empowering magic of storytelling beyond trauma.

In our conversation, Dillon talks about key concepts within Indigenous-led science fiction and offers a genealogy of the term “Indigenous Futurisms,” going back to authors like Gerald Vizenor and Diane Glancy; in doing this she provides a precious bibliography at a time when some of the most exciting science fiction writing today is coming from nonwhite authors. She considers stories with topics ranging from technology, environmental justice, and relations between human and other-than-human creatures, showing that thinking with science fiction offers a rich path to decolonize the notion of science itself, freeing up space for political imaginations beyond a one-world future.

—Pedro Neves Marques

***

Pedro Neves Marques: Your seminal 2012 anthology Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction is a collection of science fiction literature by contemporary Native writers from North America, the Caribbean, and Australia. In it you characterize the term “Indigenous Futurisms” through different categories or concerns, all of which have both aesthetic and political connotations. These categories are: Native slipstream; Contact; Indigenous science and sustainability; Native apocalypse; and Biskaabiiyang, meaning “Returning to Ourselves.” Could you describe these ideas briefly and how they might prove helpful to better understand the scope of Indigenous Futurisms?

Grace Dillon: I want to make clear that, as I was creating these categories, they seemed very flexible and moveable to me. I first asked each writer how they defined science and what they saw as science-fictional about their writing, and only then about Indigenous Futurisms. So these categories came to me from their own voices and what was available at the time. It’s true that I didn’t get everyone in; there were plenty of other voices that should’ve been a part of the collection. Another thing about the book is that, instead of it really being a story-by-story collection, I was more interested in getting people excited about the authors and their many writings. That’s why sometimes there are just snippets of novels, rather than full short stories.

To start, “Native slipstream” came from the fact that there were several ways of thinking and writing about space-time—not as separate subjects, like “now let’s talk about space” and “now let’s talk about time,” but rather as space and time flowing together, like currents in the same navigable stream. While sorting through my research, I was also reading the latest physics of that moment, with multiverses and parallel universes actually being verified by scientists. It was an exciting moment, because my own Anishinaabe traditional knowledges, gikendaasowin, and even our sacred stories, aadizookaanan, were being honored by these scientific discoveries, by “sciences in the making,” as Bruno Latour refers to the stage when proofs are still in process or remain an artifact rather than a fact. I took great delight in that and called this aspect “Native slipstream” in honor of those much more ancient forms of thinking, and also in honor of writers like Anishinaabe Gerald Vizenor and Cherokee Diane Glancy.

Vizenor and Glancy were writing way back before computers, and were among a bunch of artists and authors who couldn’t get published by mainstream presses because their ideas just seemed so strange and unusual. So what they did was to create an exchange of self-publishing called Slipstream Press, borrowing the aeronautical term “slipstream” and then opening it up to experimental forms of writing. This was way before Bruce Sterling is said to have coined the term in the science fiction field. They were viewing and talking about their work as slipstream back in the 1970s, while Sterling only came up with the term during the cyberpunk days, in his 1989 fanzine column sf Eye. What’s fascinating is that a lot of science fiction academics will start with Sterling and say that he is where slipstream comes from, overlooking these BIPOC voices that were already writing and sharing it among each other.

For its part, “Contact” was and remains a decolonizing feature of many Indigenous stories because, of course, contact is such a big topic in science fiction, especially in the form of contact with alien peoples. For us Native Americans and/or Indigenous peoples throughout all the Americas—South, Central, and North—contact carries political reverberations. Take these myths that talk about Indigenous peoples having visions or prophecies about white people coming and making contact. White people misunderstood, for example, our Anishinaabe word manidoo, which was used during that moment of contact or encounter with others; it can mean “spirits,” but it doesn’t mean “gods” or “deities.” The immediate perception of the white settlers was that somehow they themselves were the gods who had arrived, whereas for Anishinaabe people like me, manidoo means: this is such an amazing event that it will shift our lives irremediably, for all of us, not just for Indigenous peoples, but also for settlers or whoever is involved in that contact. In other words, contact is such a momentous occasion that it will genuinely change relationships within the common pot—I use this term in honor of Abenaki Lisa Brooks’ explanation of the common pot as a space-time that is intended for all who come to its area to live relationally and comfortably together. The myths about idealizing settlers and settler nations at the time of contact are a huge misunderstanding that are still promoted today.

PNM: You already mentioned science, but do you mind going back and talking a little bit more about the notion of “Indigenous science and sustainability”?

GD: Nowadays, I think in terms of Indigenous sciences rather than science. I feel that’s the way we should think about all sciences, as plural, whether we label them Westernized, Indigenous, or whatever form they may take. Let me quote from Gregory A. Cajete, a member of the Santa Clara Pueblo Nation who has worked in the field of Native science or sciences. He asks, “What is Indigenous science?” According to him, “It is knowing how to live in a place sustainably.” In his Indigenous Community: Rekindling the Teachings of the Seventh Fire (2015), he writes: “Over the years I’ve developed some working definitions. Here is how I defined that term. A body of traditional, environmental, and cultural knowledge unique to a group of People that has served to sustain that People through generations of living within a distinct bioregion.”

So you have this kind of intergenerational knowledge, but you also know that you’re always learning more. This is another definition that he gives: “Indigenous science is founded on a body of practical environmental knowledge that has been learned and transferred over generations of a People through a form of environmental and cultural education that is unique to the People.”

Lastly, Cajete says: “Indigenous science can also be described as guiding thoughts and stories about the world uniquely based on the lived experience of a group of People.”

Indigenous science, then, is a process for exploring, which reminds me, again, of Bruno Latour’s “sciences in the making.”

What I love about current Indigenous Futurisms and how they’re changing is that they aren’t constrained by this binary between Western science and Indigenous or non-Western science. One example is Nalo Hopkinson’s novel The New Moon’s Arms (2007), set in the Caribbean. There’s this scene close to the end of the book, after the characters have suffered all of this environmental and extractivist injustice, where the grandmother is passing on her traditional ways of knowledge to her grandson but, since he goes to school, they’re actually teaching each other. “Intergenerational” doesn’t imply a hierarchical, top-down elders’ passing of knowledge only. It’s more of an exchange of ideas. This is what I see going on between generations in our Indigenous communities right now. In the science fiction field, my goal is to quietly change the mission for the top-notch journals in the field that are still simply clinging to stories about advanced technology and this linear way of thinking about knowledge as mere accumulation.

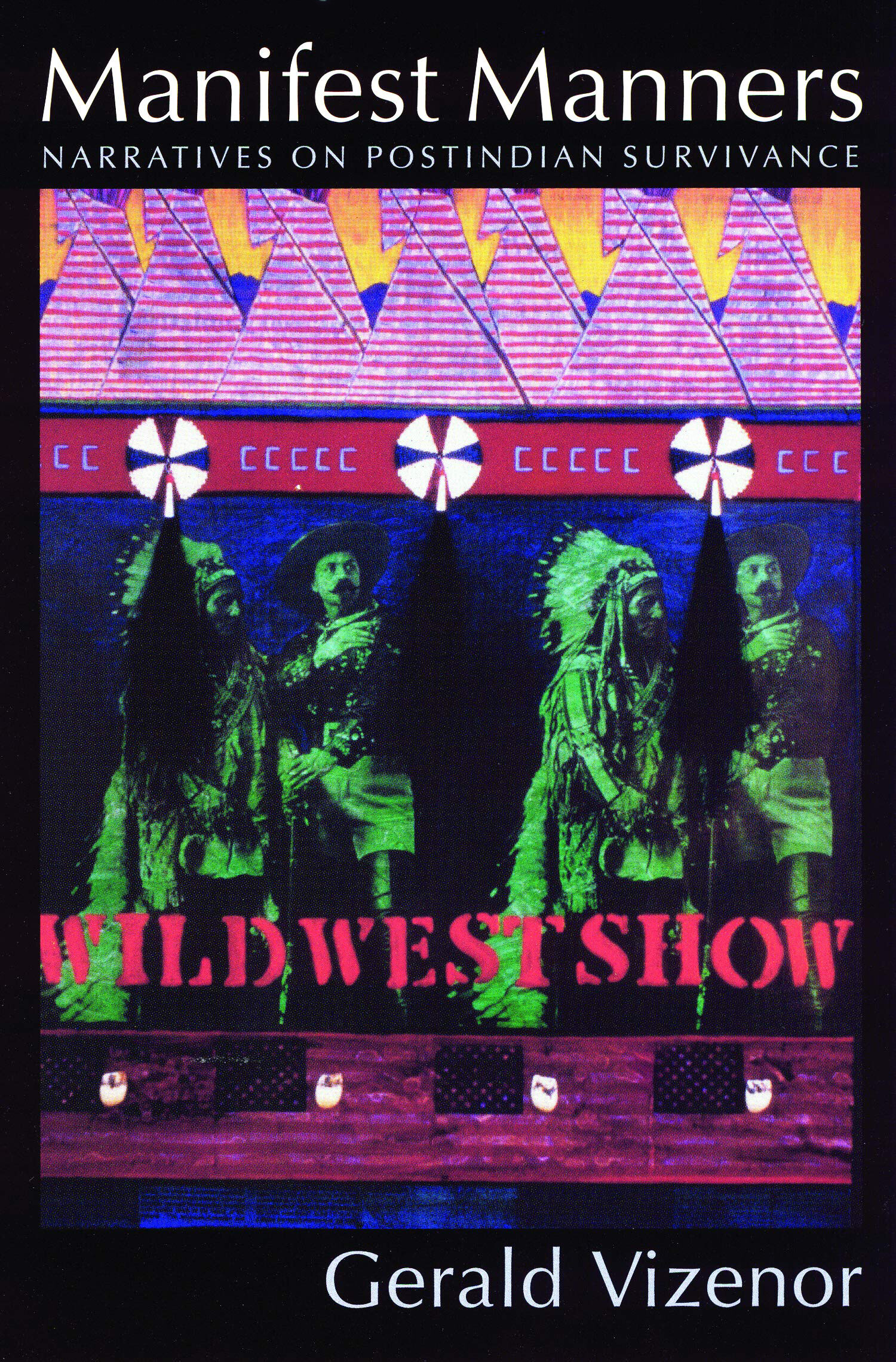

PNM: You also speak about “Native apocalypse,” which reads to me much like Gerald Vizenor’s notion of “survivance.” In Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (1999), Vizenor explains that the end of the world has already been experienced by many people, mostly nonwhite, and still these people resist, survive, and thrive. It seems like this is something that white people have only recently caught up with, now that we’re also somewhat facing our own end of the world. This is quite intriguing, because to me the current obsession with dystopias, in books and television series, reads as a final appropriation of sorts. While Indigenous peoples have lived through apocalypses for centuries, white people now steal even that space, or airtime if you will, of both Native trauma and survivance, only to push their own anguish, seemingly erasing any colonial differences with statements like, “We’re all together in this climatic mess.”

GD: As Indigenous peoples, we’ve already experienced forms of genocide, including biowarfare, with blankets being contaminated with smallpox and then handed out as a way to decimate our people. You can connect this with Vizenor’s notion of survivance—telling stories to overcome the lived experience of tragedy, dominance, and victimhood. The important thing is not to be subsumed by those experiences. In Waubgeshig Rice’s novel Moon of the Crusted Snow (2018), you have an Indigenous community where all of a sudden the power is cut off and there’s no internet or any connection to the outside world. To help everyone survive, what the community does is return to traditional protocols: if anyone hunts a caribou or a moose they don’t hoard but share it with everyone, starting with the elders. To me, that is the hope that underlines the reality of Native apocalypse: you lived through it, so you may know how to pull together as an Indigenous community through any kind of crisis.

PNM: That connects to how you manage to go back to the community through Indigenous Futurisms, which is what is referred to as Biskaabiiyang, an Anishinaabe word meaning “Returning to Ourselves.” From what you explain, this implies a sense of reencounter and pride in Native traditions, not simply to preserve them but to push them towards better futures.

GD: For us Anishinaabe, Biskaabiiyang is a specific term that means “returning to the woods,” because we’re woodland peoples. For example, I grew up growing my “three sisters”—that is, corn, beans, and squash—along the edge of the forest, using what people now call sylvan culture or permaculture. It’s curious how this counters the perspective of classical authors like Dante in early modern Europe or, later, Edmund Spenser, an important Renaissance poet, who view the woods as this terrifying presence. Why is this decolonizing? Because through boarding schools and many other colonial experiences, that fear of the woods creeps in.

PNM: In Brazil, the word that the postwar fascist regime used for clearing certain areas of the country to allow for so-called development was “pacification,” which was applied to both Native peoples and the landscape. Instead of saying that they would cut down a forested region or displace and “educate” its local Native communities, they’d call the whole process “pacification.” So that’s become an extremely loaded word in the Portuguese language. Beyond the term’s historical associations with the military fascist regime, it reinforces the colonial notion that equates Native peoples with “nature” and a violent wildness, like the threatening woods that you just mentioned.

Going back to your ideas, it’s been almost a decade since your anthology Walking in the Clouds was published. And what a decade it was! We saw an intense transformation in the field of science fiction, with a wave of Indigenous, black, Asian, and many other nonwhite authors, including women and queer writers, being published and offering some of the decade’s most challenging stories. N. K. Jemisin, Stephen Graham Jones, and Hao Jingfang are well-known examples. At the same time, there were tremendous political upheavals and now-iconic Indigenous struggles, like the NoDAPL movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline in North America. Do you feel certain things have changed in the space both of indigenous struggle and of science fiction since the book’s publication?

GD: A key change has been the integration of racial justice with criminal-justice reform. A good example of a story that portrays the racism of incarceration is Australian First Nations’ writer and director Wayne Blair’s new television series Cleverman. It tells the story of these supposedly nonhuman people called the “hairies”—and they are hairy!—as a way to exaggerate and exemplify how Australia’s First Nations people are treated, especially in urban areas. It really speaks to issues like immigration reform and the caging of people by showing how they are interrelated issues.

Climate justice is another issue that’s being addressed in fiction right now. I don’t mean that stories are simply talking about climate change, but that the stories themselves become forms of climate justice. Take Waanyi Nation Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book (2017), which deals with the contamination of First Nations’ rivers and waters. Or, also in Australia, the works of Wirlomin Noongar writer and poet Claire G. Coleman, like Terra Nullius and The Old Lie, the former a clear take on climate injustices. Anishinaabe Louise Erdrich’s novel Future Home of the Living God (2017) is a really interesting take on decolonizing the Anthropocene. The main character is a pregnant woman who is ready to have her little one in what other non-Native and non-BIPOC people in the story view as a mutated or regressive state. There’s also the novel Corvus (2015) by Harold Johnson, who is Cree. The novel is very cyberpunk, with its urban forms of technology, but in this world there’s this particular way of traveling where you can climb inside a mechanical bird to glide; the hero picks a raven but soon learns that the raven is actually a bird-person who brings him back to his own Native community out in the mountains and hidden valleys.

PNM: Do you find that multispecies entanglements and the inclusion of nonhuman beings has also grown in visibility, within and outside these stories? I’m asking this because, for instance, in Brazil, debates about the rights of nonhuman or other-than-human beings have been key to Indigenous and anthropological discussions for at least the past two decades. There, the debate mostly centers around plant or animal persons, and moreover the anthropological question of “what is human,” from an Indigenous point of view. That is, the knowledge that terms like “animal,” “plant,” “human,” and “spirit” may mean something much broader than how modern sciences define them.

GD: Back in 2012, I was talking about animal persons, rock persons, phenomenological persons, plant persons, and so on, and you could sense a quiet skepticism among some people. They would see it as a form of animism, when in fact I was talking about sciences. For example, plants literally converse among each other; plants that live in toxic areas warn other plants to stay away. There are many examples of nonhuman persons in fiction about sciences. Take Thomas King’s novel The Back of the Turtle (2014), a story about a First Nation scientist who is developing chemicals for a bioengineering company that is truly extractivist and toxic, until he sees how that’s impacting the land, together with its animal and plant persons, and he is thrown into a crisis. Does he want to be a scientist? Or at least a scientist in that kind of context?

PNM: That story reminds me of Larissa Lai’s latest novel, The Tiger Flu (2018), and its post-hardware future, where plant seeds become technologies and the world has shifted entirely to wetware, cell culture, and herbology. It speaks to what you’re saying about fiction that responds to knowledges of the land, rather than science fiction being restricted to “hard” technology like spaceships.

GD: Speaking of outer space, one indication of how much things have changed is the fact that I was invited to the advisory board of what’s called ETHNO-ISS, an organization that focuses on the International Space Station and life in outer orbits. They want people working on futurisms, including Indigenous Futurisms. Right now, I’m also working with three other editors, Isiah Lavender III, Taryne Taylor, and Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, on a Routledge collection on Alternative Futurisms, or “Co-Futures” as Bodhi has coined it. That includes Afrofuturism, African Futurisms (with Nnedi Okorafor’s definition of this in mind), Indigenous Futurisms, Latinx Futurisms, Gulf Futurisms, and Asian Futurisms. I’ve noticed that the mindset is shifting for the better, I think; it is becoming more inclusive and diverse.

PNM: You always say “Indigenous Futurisms,” in the plural, rather than in the singular, just as you say “sciences” instead of “science.” I’d like to ask about this plurality of futurisms. Connected to this, it comes to mind that instead of painting the rosy multicultural future world imagined by much optimistic science fiction and liberal politicians, many of the writers whom you reference don’t shy away from historical, racial, and thoroughly cosmological tensions. Would you like to comment on that?

GD: Indigenous Futurisms, in the plural, was a choice that I made after 2012. Until then I was calling it “Indigenous Futurism.” The choice reflects the richness of Indigenous communities globally. I based it on the process and legal struggles that led to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, with an s. It took about three decades of struggle to get that letter s in there. The reason that it’s so important is because our nations can cross borders of what are perceived as other nations. My own nations are that way. Bay Mills Nation in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, in the US, and Garden River First Nation, in Ontario, Canada, belong together, but because of the 49th parallel, it’s Canada on one side and the US on the other. We’re not just one people, we are peoples and our lands can encompass more than one settler nation. So Indigenous futurisms became a political pushing-forward of decolonization.

Then, talking with other people, they said, yes, we should call it African Futurisms, Latinx Futurisms, and so on. It’s been very conversational. We left Afrofuturism alone because that was really the starting point, with Alondra Nelson’s 2002 Social Text issue on Afrofuturism. Mark Dery is given credit for coining the term “Afrofuturism” back in 1994, when he edited the collection Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, where he interviewed Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose. Once again, final credit was given to a white man, just like with slipstream. For my part, I start that discussion on Afrofuturism with Nelson; her collection is the first genuine piece of scholarship on Afrofuturism that brings in different African-American voices. In 2003, when I coined the term “Indigenous Futurism” (later “Futurisms”), I was doing it as an homage to Alondra Nelson’s collection.

PNM: Interestingly, your anthology includes Indigenous writers from across the world, particularly those subjugated by British imperialism and the structures it left behind. To ask for the inclusion of South American Native voices perhaps would have been too much, but I wonder how that speaks to a divide between North and South America. In the North, thanks to voices like yours, Indigenous Futurisms have become a political and aesthetic project. My knowledge only goes so far, but I haven’t seen much on Indigenous Futurisms in Brazil, which is what I’m most familiar with. (I’d say it’s different with Afrofuturism though.) In Brazil, you may even find a certain distrust in the notion of futurity itself. I can understand that, because the relation between the future and technological advancement leading to a “better world” is fundamentally a modern Western invention. And we know how that future not only led to but is based on the colonization of other peoples’ worlds, including their particular perception of technology, humanity, and the environment. In those techno-scientific, linear, or messianic terms, Native peoples were and continue to be robbed of any future, be it access to white privilege or their own cosmopolitical sovereignty. How might “Native slipstream” and the concept of survivance respond to this possible frustration and offer other ways of understanding the future beyond settler time?

GD: I should apologize, because when I edited Walking the Clouds I really wanted to bring in Indigenous Latinx authors from countries in South America. I speak a bit of Spanish but not fluently. I would have needed someone to translate those stories for me. Now things have changed. Now there are many more collections in many languages, and stories are being translated.

In terms of the future, my Anishinaabemowin language has a word, kobade—a very small word, but in reality an extremely sophisticated concept. The idea is that everything that’s in the past and the future is also in the now, but it’s not as simplistic as that. It’s more like there exists a spiral of intergenerational connections, so that even if you are in the present you have spirit persons at your side; they can be ancient spirits, considered to be from the past or from the future. Kobade is the recognition of all persons, not just human persons, and of all the intergenerational connections that we have, which are never linear, but spiral. In my language some people may describe it as a chain, wherein we’re connected to each other, so that the future is always containing the past and the present; I don’t use the word “chain” because I work in Black Studies and it just feels heavy and inappropriate. I use the image of a spiral. This is very different from the former science fiction model, what was called “extrapolative fiction.” This word came directly from Robert A. Heinlein, who took the idea from mathematical equations, where you pull something out of the past or the present and draw this imagined plausible future from one dot to another. That’s an extremely linear concept, too simplistic to allow other forms of thinking. For example, we just don’t arbitrarily choose a certain point in the past when writing and developing characters; there can be all kinds of remnants of pasts, presents, and futures.

PNM: That’s such a fundamental rupture in the practice of science fiction. Of course, the 1960s and ’70s New Wave generation already broke with that more messianic, technologically bound view of science fiction. But Indigenous Futurisms introduce, to my mind, a rupture not only in the conceptualization of time but also within the very topic of science fiction itself. It’s science fiction, not future fiction. It’s about the science, first and foremost.

Film still from Helen Haig-Brown’s 2010 short film The Cave. Copyright: Helen Haig-Brown.

GD: When talking about her 2010 short film The Cave, Helen Haig-Brown says that what she did in the film was to take the fiction out of science fiction. The film tells the story of a bear hunter who ends up in a cave, inside an alternative world where people speak to one another telepathically and you have these spirit beings floating in the air; in the credits they’re actually listed as “Spirit Woman 1,” “Spirit Man 2,” and so on! The hunter meets a telepath spirit woman who warns him, “You’re not ready for this knowledge, you need to go back,” and there’s a sudden clap of energy that pushes him back to the woods, where he finds that his horse is now a skeleton, as if he’s been gone for decades. What’s so interesting is that Haig-Brown was filming a recorded Tsilhqot’in story, which her tribal nation gave permission to adapt, and these were real people from the community who agreed to participate in the film. While the film may appear as science fiction, it’s taking the fiction out of science fiction. This is something you see in many Indigenous Futurisms.

PNM: How do you see the relation between science fictions and Native myths and mythology? While the modern mind may eventually recognize the cultural value of Indigenous myths, it refuses to see them as scientific evidence. I wouldn’t want to project a meaning onto these stories, so I say this very carefully, but although in Brazil you may not find a great presence of Indigenous science fiction, Native traditions and myths almost seem to perform science-fictionally, in how they both rupture modern categories and expectations and allow for imagination beyond colonial frameworks.

GD: I have a lot to say about this. The first thing I’d like to do is to eradicate the term “myth” or “mythology,” because that implies that these stories are false or that they are fictions that should be questioned. Instead, what I do—and this is what I grew up with—is to call them “stories.” Everything is storytelling. Indigenous sciences are embedded in stories; this is how we share our Indigenous sciences.

I grew up in a pacifist anarchist community that was Anishinaabe-founded, at least to some degree. So, when I read Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed, I could absolutely understand the whole process of community and of shunning or shaming a person as a form of power and control, but also the recognition of combining art with science, rather than understanding them as separate. Although her story is science fictional, by acknowledging the role of storytelling in this combination between art and science, Le Guin again takes the fiction out of science fiction, and works with other forms of science.

Our word aadizookaanan means “ceremonial stories” or “sacred stories.” Most First Nations don’t share those sacred stories with outsiders. However, in 2012 many of the nations I belong to—and you should know that we Nish peoples are often called the pacifist-anarchists among other Indigenous nations—got together and decided to share not only our gikendaasowin, meaning herbal knowledge and science and how they interact with ceremonies and songs, but also our aadizookaanan. We decided that some of our sacred stories needed to be shared globally, because they were necessary right now for dealing with Mizzu-Kummik-Quae, Mother Earth. So the reason I’m interested in science fiction is that when I was little and we had firesides, sweats, and other ceremonies, we were telling stories about star peoples that came to earth in, basically, space canoes. For me, the concept of a spaceship was not unusual. And, of course, we are all star people. We are made of stardust, which is scientifically accurate. Everything is made of stardust.

Category

Subject

A version of this interview appears in the anthology YWY, Searching for a Character Between Future Worlds: Gender, Ecology, Science Fiction, ed. Pedro Neves Marques (Sternberg Press and CA2M, 2021).