Contemporary art has always been at the forefront of artistic practices that venture to replace aesthetic narratives with social activism. In this text, however, we will examine the theater’s rejection of its own aesthetic methods and expressive idioms in the name of “direct” democracy, as well as the sociopolitical and artistic effects of these experiments. Has the notorious sacrifice of dramatization (i.e., the theatrical episteme per se) in postdramatic theatrical practices proven politically effective and aesthetically radical?

Researchers have argued that there were two motivations for the postdramatic turn in the theater. One was post-disciplinarity’s dissolution in direct-democracy practices. The other was the attempt to borrow the performative poetics of contemporary art, which, as theater researchers falsely imagined, was based on the artist’s direct, living, nonsymbolic presence in the performative process. This is what differentiated the artist from the actor, who was immersed in the temporality of role-playing and staged repetition. Theater scholar Erika Fischer-Lichte defined this presence as “autopoetic,” as opposed to mimetic.1 This nondramatic, non-staged presence on stage has come to be called “postdramatic” in almost all critical theater studies.

It is important to deal with two erroneous assumptions made by the postdramatic theater. First, what the theatrical gaze sees as the “living” presence within performance in contemporary art is not alive. Second, spontaneous behavior, liberated from the discipline of acting and theatrical staging, is not identical to emancipating citizen and society.

In her book The Transformative Power of Performance, Fischer-Lichte encourages theater workers to borrow the anthropology of “real” presence from performance in contemporary art. The same appeal runs through Hans-Thies Lehmann’s Postdramatic Theater.2 In a similar vein, the choreography theorist André Lepecki calls for immersion in the “authentic present” instead of the fictitious narrative depiction that occurs in ballet choreography and classical music. Only in this way, he argues in Exhausting Dance, can we rid ourselves of the authoritarianism of discipline in the performing arts.3 All three works argue that the score (the original text) and the rehearsal aspect of theater and choreography are rudiments of Western European modernity. Lepecki believes that the compressed time of the performing arts is an allegory of Western Europe’s colonial geopolitics, which has been reflected in the performing arts in the form of drilling (military science) and commands (promulgation of laws).

Lepecki shows that the composed and choreographed temporality of dance (and therefore of music and the theater) is based on the transient eventfulness of the “present moment”; that is, the performing arts were shaped to pursue this lost moment of the beautiful present and mourn it. Although Lepecki does not mention it, we would do well to recall the Orphic genealogy of the performing arts and the theater in particular. After all, Orpheus’s loss of Eurydice is the lost “present” moment to which we shall have to return endlessly, repeating it because it is impossible to compensate for. This original grief has molded music, the theater, and later, choreography. Lepecki argues that, given this constellation, the present moment inevitably turns out to be a lost past, a past we never cease pursuing. That is why the classical performing arts are kinetic and involve perfecting the configuration of this kinetics. After all, what matters in this case is clutching at the beautiful as it escapes, hence the kineticism: the work is constructed as a series of such “beautiful” but passing moments.

Modernity’s aesthetic context is thus based on the pursuit of a lost object. That is why the kinetic body must be artificial, disciplinary, sculptured, and architectonic—in music, in the theater, and in choreography. Western European modernity’s performative paradigm is orchestrated in such a way that the body must acquire impossible abilities and exist in “impossible” conditions, because every moment that we lose irretrievably in a time-dependent work must be perfectly beautiful. Performance should consist of these fleeting moments, whose disappearance is compensated for by the fact that every moment is a perfect monument to its own disappearance, with the viewer observing the ideal’s retroactive progress. The work of art, whether theatrical or musical, is composed of extreme moments that drop out of the chronicle of time: the work is thus opposed to the chronic present.

It is just this exaggerated shaping of time in the theater, music, and choreography that Lepecki sees as evidence of violence against time, the body, and society—a violence that attempts to generate perfect essences and forms that are not equivalent to life. Therefore, instead of this exaggerated form of time, Lepecki advocates an expanded, democratized, and anti-kinetic duration—a present without past and future that does not trigger memory and bid mournful farewells to the transient present. This implies a return to contemplative and solipsistic nonaction, to natural behavior and the body’s presence in the here and now—that is, to the same “living” presence that Fischer-Lichte also advocates, mistakenly expecting that it can be found where performance appears in contemporary art. In this disposition, instead of representing events and deeds, radically dramatizing them, and conveying the metanoia in the individual’s life, both the body and time should unlearn these modes. Accordingly, they should liberate themselves from the practice of repeated rehearsals in order to find a realm where they can simply be with all the naturalness and intimacy of dissolving into duration, rather than performing something. If this liberation succeeds, there will be no need for the fulfillment of performance—no need to perform and materialize components that materialize even as they disappear.

As Lepecki’s analysis shows, it is not only a matter of rejecting dramatization, but also of rejecting the special temporalizing of the work, thus added to the chronic time of existence. Most practitioners and theorists of the theater and modern dance argue that the rejection of all forms of fine-tuned, rehearsed, fictitious performativeness democratizes both the performing process itself and, consequently, the types of presence in public space. Moreover, it enables two milieux—theatrical action and social discussion, the stage and the agora (“agonistic pluralism,” to borrow Chantal Mouffe’s term)—to interpenetrate. Not only does democratized postdramatic action seemingly come down to earth and infiltrate the public space, but civic discussion, by rejecting dramatization, also takes to the “stage” to allow simple forms of conviviality and the controversial compatibility of bodies to find a voice and be presented publicly.

Theater curator Florian Malzacher argues that one can politicize the theater by removing the disciplinary figures of the actor, the dramatic role, the director, and the event from the action, since these components only reproduce a particular social problem, rather than revealing ways to solve it.4 Instead of fictionally sublimating the event, merely residing in a real social or existential situation is a much more effective way of understanding its essence. The same stance made Lehmann insist much earlier, in 1998, that the theater should rely more on its phenomenological structure, in which the transmission of signals and their reception occur in the same common space and time. (I do not agree with this stance and will explain why below.)

According to Malzacher, if dramatic fictitiousness were abandoned, the theater could focus not merely on certain political issues, but could be the very site of politics, becoming a kind of public parliament within the theatrical institution. The representative model of the theater, based on actors’ performance of roles, is also socially outmoded. In a truly civil democratic society, a member of the middle class would not portray a poor person, a resident of the rich European north would have no right to speak for an oppressed southerner or a refugee, and a white person would not play a person of color. That is why one should simply be who one is in a particular context, rather than playing the role of someone else, and those who are not involved in the institutional theater should be authorized to appear on the stage both as agents of the performance and as debaters, thus turning the theater into the site of Mouffe’s agonistic pluralism.

***

In the discussions I have named, contemporary art, in which the individual’s or the body’s intervention in public space is one of the most important tropes, has become a model of direct political participation for the theater. However, there is more than meets the eye in the naive interpretation of contemporary art’s “living” (as opposed to rehearsed) presence, as promoted by the adherents of the postdramatic turn.

Interestingly, when Fischer-Lichte, Lepecki, and Malzacher call for the radicalization of theater and choreography, they often cite textbook examples of performance in contemporary art: for example, the performances of Marina Abramović (cited by Fischer-Lichte) and Bruce Nauman (cited by Lepecki), and the political ready-mades of Jonas Staal (cited by Malzacher). They identify these performances with post-choreographic or postdramatic practices in the theater and choreography, such as the post-choreographic performances of Xavier le Roy, the productions of Boris Charmatz, and the performances of Maria La Ribot. But try as the abovementioned theorists might, and despite the frequent use of these postdramatic practices in museums and exhibitions, they have nothing to do with contemporary art. For Fischer-Lichte, Abramović embodies the rejection of the fictitious image of pain in the theater and the autopoetic rejection of theatrical mimesis. For Lepecki, Nauman illustrates the destruction of composed temporality, the end of the choreographic score, and the discovery of a new form of solipsistic intimacy. For Malzacher, Jonas Staal’s 2012 project New World Summit (2012) is a specimen of agonistic pluralism. The project was presented in theaters as a real ready-made of a congress of unrecognized states, confirming that direct democracy is possible within the walls of the theater, and this is exactly what the repertory theater lacks.

Performance in Contemporary Art Is Not Performative

Now let us return to the two abovementioned assumptions made by the postdramatic theater and recall what their fallacies were.

1. What the theatrical gaze sees as a “living” presence within performance in contemporary art is, in fact, not.

2. Democratic liberation from the discipline of acting and the framework of theatrical production does not lead to the emancipation of citizen and society, but only reproduces the mantra of emancipation formally.

Why is the comparison of performance in contemporary art to the postdramatic theater a gross aesthetic and epistemological mistake? Because performance in art is not and has never been a living presence that is perceived and described phenomenologically. Performance in art, even as collective action, is neither a civic act nor direct democratic action. In the performances of Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Valie Export, and many others, it is vital that the artist’s body or their actions are transformed into a materialized conceptualized exhibit—in a sense, into the embodiment of an abstract concept. They therefore have little connection with the autopoetic freedom of expression about which Fischer-Lichte writes. What the postdramatic theater theorists imagine as the phenomenologically registrable, immediate, and nondramatic presence in contempoary art is situated outside the dramatic and postdramatic. Why? Because, while the theater, by way of renewing itself, still employs early twentieth-century methods, thus merely demonstrating or deconstructing the medium, art has completely abolished itself as art in order to finally rid itself of all dependence on the audience and establish itself as an institution that references its own emptiness, its own nonexistence. Again, even when the theater explores its own thresholds and tries to introduce self-reflection into the performance, it remains at the level of merely critiquing itself as a medium. The theater has never committed total self-abolition. That is why it prioritizes reception and observation and the need for an audience, despite sometimes engaging in radical experiments that can be difficult to digest. This happens because only the medium-related components of the theater are conceptualized or abolished, while the phenomenological structure itself, which involves observing and registering the action, is not sublated. In other words, the contemporary theater employs various experiments: it dabbles with the absence of action, attempts to be immersive, or tries to rid itself of the actor and other disciplinary theatrical epistemes.

The same thing has been happening in dance, which has been trying to rid itself of choreography and the dancer. Generally, both contemporary theater and contemporary dance have been trying to remove mimetic constructions, showing the viewer the very process of their own disintegration. Nevertheless, both still need an audience on hand to observe their deconstruction. Contemporary art and performance’s appearances in it have no such need because of modern art’s absolute self-abolition. Malevich’s Black Square (1915) and, later, Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) devastated the institution of art to such an extent that it became an ideal concept that no longer had any need whatsoever for observation or spectators. That is, the institution of art had to abolish itself totally in order to establish the new institution of contemporary art.

That is why each discipline—theater, dance, cinema—has its own theory. But the difference between the theory of art and the theories of theater, literature, cinema, and choreography is that contemporary art itself is already theory, as it were: it does not need a theory describing it. That is, as a result of art’s self-abolition, that institution has no aesthetics. It has no autonomous phenomenology, only theory. Despite its modernization, the theater has not undergone the complete eradication of its substance, the abolition of the perceptual context of the discipline itself. Consequently, the substance of the theater has not completely left it, although many people would like this substance to be similar to art—to become more “defamiliarized,” more socially engaged, and therefore more appealing to today’s progressive viewer.

Why “Soft” Democracy Is Not Emancipatory

During a discussion after the premiere of a dance performance of hers, choreographer Alexandra Konnikova, explaining the ethics and poetics of contemporary dance, actually voiced all the postulates outlined above in connection with Lepecki’s critique of ballet choreography. In contemporary dance, the body is anti-acrobatic: it strives to naturalize space and time and the modes of existing within them.5 Our being in this milieu should not be excessive: rather, it should involve self-therapy and self-observation of the body’s internal biorhythms (thus recalling Lepecki’s protracted present tense and his defense of self-observation and solipsism). We see such bodies in productions by choreographers such as Charmatz, La Ribot, Le Roy, Constanza Macras, and Jérôme Bel, among others. But let’s compare these postulates about the body’s naturalization with Grotowski’s and Artaud’s fundamental and opposite demand for supreme excess, for pushing the actor’s body and mind to the brink. Artaud’s principal metaphor is “athleticism,” acrobaticism.6 For Grotowski as well, the body must be raised to a superhuman sensitivity to become spirit. The body’s acrobatic and athletic excess produces, as it were, an “acrobatic” amplitude of consciousness, soul, and spirit that endows one with the physical and spiritual abilities to take action. In other words, acting is not so much a profession as a specific psychophysical training that prepares one to perform deeds. This body is neither individual nor solipsistic: it is ideal and therefore universal. Even the Brechtian acting method, which postdramatic theorists often consider the forerunner of post-disciplinary theater practices, does not so much upset the discipline as toughens it, supplementing the actor’s training with critical civic meta-reflection. In this case, the avant-garde’s criticism of repertory theater contradicts critiques of “academic” theater found in so-called contemporary postdramatic theater. Avant-garde theater criticized mainstream repertory because it weakened the excessive components of theatrical performance—that is, because it lacked purely performative, radical, truly dramatic components. On the contrary, current adherents of the postdramatic aesthetic (Fischer-Lichte, Lepecki, Malzacher) criticize mainstream repertory theater (in which there is nothing left of the rigor of the dramatic genre) for its excessively rigid discipline.

Now let us ask ourselves a question. Can a body that limits itself to a mere natural existence in a particular enduring present, a body for which its own natural solipsistic precarity suffices, really be political? Is not freedom and social activism replaced in this case by the mere demonstration of one’s lifestyle, of one’s trauma? Consequently, isn’t what we observe only the promiscuous admission of all arbitrary forms of behavior into the social and artistic space, rather than a rebellion on the part of these forms? The allusion to performance in art is irrelevant here, because when performance shows up in contemporary art, the body and its presence—only simple and unrehearsed at first glance—are in fact rigidly conceptualized and theorized, and turned into an art exhibit, as argued above. In the contemporary postdramatic theater and contemporary dance, however, we observe an endless stream of individualistic and solipsistic self-expression instead of conceptualized ready-mades. As a result, instead of the dimension of the “general” or “universal” in postdramatic practices, we observe a sociality that appears, rather, in the image of a panopticon of hybridized individuals, whose unification is possible in the sense that each of them is provided with a mini-arena for demonstrating their everyday identity. “Democratization” is reduced to this demonstration. Intense forms of emancipation emerge, however, when the individual seeks the dimension of the “general” in their identity, and not when they are limited to the individual right to everyday life and the narcissistic demonstration of this right.

Post-disciplinary democratic performativity consists in everyone’s being allowed not to make an extraordinary effort, as if any extraordinary effort can only be the Big Other’s authoritarian imperative, rather than an ethical, civic, or creative achievement.

In The Psychic Life of Power, Judith Butler accurately describes the type of socialization intrinsic to the post-disciplinary society, in which gender freedom is not the social horizon of universal emancipation, but that minimal area of “bare life” that might escape the regulatory apparatus.7 In this context, gender identity—as a type of social emancipation—is empowered only within the realm of the clinic. In other words, gender freedom and other representations of identity freedom are realized in the capsule of the clinic, in the mode of freedom from society, rather than freedom for society (that is, for the “universal”). Liberal democracy in the broad sense is a democracy of individuals free from society, united in a quasi-community similarly free from society. This motif runs like a dotted line through Foucault’s analytical critique of post-disciplinary neoliberal society.

Paradoxically, the openness of the public sphere does not involve the dimension of the “universal,” but a democratic consensus about each individual’s freedom from the commons, from society, because the “universal” is associated with coercion and excessive methods of creative work. In addition, under capitalism, work itself is so excessive and exhausting that creativity must suspend all species of coercion and regulation. On the contrary, all manners of anarchic and perverse everyday life are permitted in the solipsistic quasi-clinical capsule.

Underpinned by this rationale, the theater director or playwright thinks that if they equate the artwork with the everyday flow of time, they will manifest their equality with ordinary citizens who do not have the opportunity to do art and thus incarnate democratic emancipation. In fact, such an approach demonstrates only the middle class’s snobbery towards society’s unprivileged strata. For the director or playwright should take into account the fact that “simple” life is not reducible to the mundane flow of time. The everyday working life of “ordinary” people and their hopes can be much more excessive, ecstatic, musical, and poetic than imagined by progressive intellectuals convinced that liberation from artistic intensities and canons would be liberating and democratic for “ordinary people.” Artists such as Michael Haneke and Lars von Trier never stop showing and proving the opposite. They depict how, in ordinary life, an excessive or a heroic act happens to be theatrical, so that an ordinary person becomes a performer of the most excessive gestures undermining daily life. In Haneke’s film Caché (2005), for example, it is the destitute Arab who proves capable of a radical, deadly performative act in the name of truth and justice.

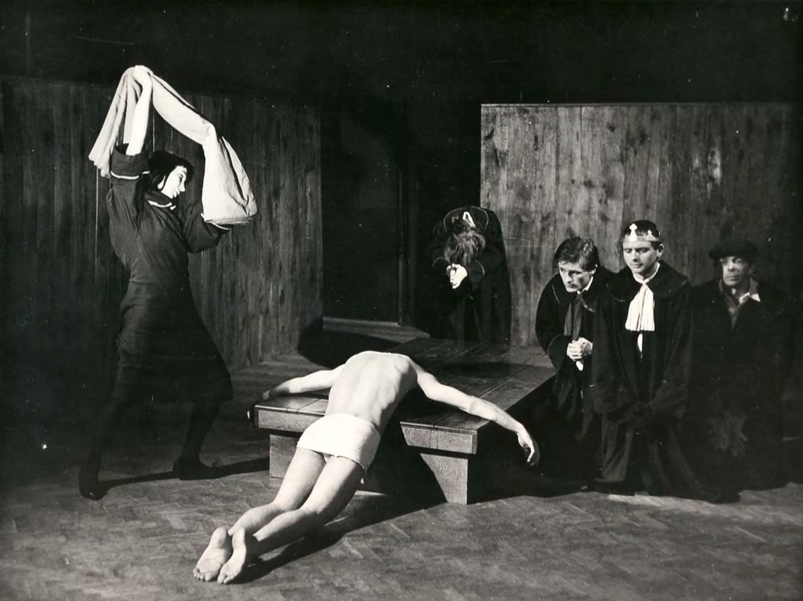

The Constant Prince, version I, Wrocław, 1965. Rena Mirecka, Ryszard Cieślak, Maja Komorowska, Mieczysław Janowski, Antoni Jahołkowski, and Gaston Kulig. Photo by the Laboratory Theatre. Reproduced courtesy of the Grotowski Institute Archives.

Five Paradigms of Performativity: The Theater of Theater

Based on the arguments above, we can provisionally divide existing practices of theater and performativity into five paradigms:

1. Performance in contemporary art. This includes only those practices that have gone down in the history of modern art as conceptualized exhibits, regardless of their processual and temporal structure.

2. Dramatic repertory theater. Most theatrical practices in the world adhere to this paradigm. Claiming to be connected with tradition, such theater has actually forfeited this connection, retaining only formal corporate characteristics and turning into a form of urban leisure. Most performances in such theaters around the world—in Moscow, Petersburg, Berlin, and London— resemble staged TV series featuring unpretentious narratives, watered down with current social problems.

3. Postdramatic theater practices. This includes both performative ready-mades that compete with performance in art and, generally, all experiments involving so-called direct, non-fictitious presence. The Rimini Protokoll troupe, the director Hannah Hurtzig, the Zentrum für Politische Schönheit (Center for Political Beauty), the early Milo Rau, and Lotte van der Berg have worked in this vein. Such practices comprise a middle realm between the traditional theater and contemporary art. The contemporary dance performers that should be mentioned in this context include Xavier Le Roy, Maria La Ribot, and Jérôme Bel, among others.

4. Art practices that borrow performing practices—dance, the theater, music—while remaining contemporary art, by way of incorporating dramatic, fictitious narratives into the works. This group of practitioners includes the Israeli artist Roee Rosen, with his opera parodies, the German artist Anne Imhof, who uses all the performing arts in her performative canvases (e.g., Faust, 2017), the Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, who employs pop and light orchestral music in his performances, and the Petersburg art group Chto Delat.

5. Finally, the fifth paradigm is the theater of theater. This is theater that, on the one hand, has intellectualized itself, disengaged from the discipline, incorporated self-observation of its own methods, along with self-reflection and defamiliarization, abandoned narrative, and also formally gone postdramatic in a sense. In reality, however, these steps towards generalization and self-reflection were made only to strengthen dramatization, so that the actor in such a performance would not just play a role, but become a pathfinder, blazing a trail to the event. Christoph Marthaler, Anatoly Vasiliev, Boris Yukhananov, Heiner Goebbels, Theodoros Terzopoulos, the early Sasha Waltz, and the visual artist Victor Alimpiev (in the play We’re Talking About Music, 2007) have engaged in making such theater.

I would like to dwell in more detail on the potential of this fifth performative paradigm. To begin with, the fusions mentioned before between theater and contemporary art have occurred because the theater is sick of its nontheoretical, nonphilosophical nature. What it lacks is knowledge of the world and a meta-position, so it is not surprising that it imitates contemporary art. Contemporary art, on the other hand, is weary of its own severity, its theoreticalness and conceptuality: it wants vitality, eroticism, history, narrative, and to a certain extent, an audience. This essay barely touches on contemporary art itself, focusing instead on how the abovementioned directors have succeeded, without abandoning the discipline of theatrical performance, in being metaphysical, philosophical, and conceptual, in defamiliarizing their methods—sometimes by invoking elements of performance in contemporary art—while deepening dramatization and, simultaneously, not imitating contemporary art. They have proven that the theater is impossible without a sensual journey to an event that cannot be understood, named, defined, and remembered outside the process of acting and performing. In this performance, the actor is no less important than the director. Or rather, not only is the director an artist and maestro, but so too is the actor; without the actor, the way to the event is impossible. Gilles Deleuze wrote that acting is not a profession, but the acquired ability to traverse an event and repeat it. That is why the actor is a medium of emancipation and a vehicle of painful intuition. According to Deleuze, the actor performs “a change of the will, a sort of leaping in place … of the whole body which exchanges its organic will for a spiritual will.”8 Grotowski defined this actorly practice as “dangerous exposure.” Hence the field of sacredness (secular rather than religious) on which all the above directors insist.

In the repertory theater, an actor is schooled like a parrot that has been obliged to play-act and dissemble, while the actor in postdramatic projects is an average joe who holds forth on the stage as if they were standing on an imaginary agora. But for the theater not to become “whispered” staging, as Artaud feared, the dramatic work must be treated not as a text, but as the score of a performing act, in which the act of performing has already taken place, for the playwright who has written it down has already performed it as an imaginary actor, rather than as a writer.

These theatrical experiments do not need to recode the discipline of the theater in the idiom of an instantly recognizable democratic mundaneness (so often confused with an analysis of modern life). On the contrary, they often resort to ancient mythology and poetry, to generalized philosophical treatises and music, thus accentuating the declamatory and prosodic components of speech. Their rejection of plotted narrative is aimed not at de-dramatizing what has occurred, but at conceptually and sensually intensifying it to clear a way to the event exclusively in the newspeak of hyperdramatized theatrical performance. Employing the compositional tools of this mode—speech, psychophysics, movement, vocal resonance, musical timbre, and poetry—it is important that the theatrical performance, no matter what event or issue it deals with, should not present a narrative construction of the event, but rather an aphoristic and poetically philosophical reaction to it. Neither genuine drama nor acting is possible in the absence of a philosophical or provisionally metaphysical perspective. The philosophical dimension generates the distance from the event that enables us to generalize the situation and the problem. Performing is impossible without such generalization, because without it, speech would be bogged down in the prosaic thickets of narration. That is why it is impossible to watch most of what’s produced by the repertory theater: speech there becomes an endless prose recitation. In other words, the repertory theater is anti-philosophical and, hence, not modern: it contains no generalized knowledge of the world. Contemporary art has such knowledge, and it is theoretical and philosophical, but its conceptual and philosophical constructions are spatial. By definition, these constructions are neither temporal nor performative, even when it comes to performance in contemporary art.

Unfortunately, the postdramatic theater, as it imitates contemporary art, cannot even acknowledge art’s theoretical-philosophical and absurdist codes. So the former has borrowed only the discourse of social engagement from the latter, along with what we have described above as the “living” phenomenological presence in the mundane present. In the theater, however, the philosophical dimension should not figure as analytical description, as in theory, nor as absurdist paradox, as in contemporary conceptual art. The philosophical, aphoristic, and poetic dimension should appear in the theater inductively, as Yukhananov has often argued—as inductive (rather than denotative) speech.9

Inductivity means that the performative and prosodic process of speech overlaps with the generation of an idea. Paradoxically, this can only happen in the mode of repetition—that is, in the mode of the actor’s “emitting” this idea not from themself, but as it were on behalf of an imaginary someone. This is the most important theatrical performance syndrome, in which the sentence (uttered by the actor) does not narrate, but repeats/performs something over and above what has happened. Outwardly, it might resemble nonsense, glossolalia, or babble, but this does not prevent such speech from constructing a philosophical dimension vis-à-vis the event. Beckett’s characters can utter nominally meaningless phrases, but these phrases are simultaneously actorly, theatrical, poetic, and philosophical. When Hamlet utters the phrase “To be or not to be,” he similarly expresses the most profound philosophical idea in a seemingly unphilosophical or nontheoretical manner. It is a philosophical phrase, but it is simultaneously playful, sarcastic, actorly, and poetic, and it is uttered seemingly on behalf of another performing subject—that is, the phrase “To be or not to be” is repetitive. Thus, the loss of the dramatic (the ludic) is fraught not so much with the rejection of plot, fictitiousness, and roles, as with the loss, first of all, of the theater’s philosophical (metaphysical) dimension. That is why the repertory theater, the postdramatic theater, and the democratic theater are often stupid, anti-intellectual, unethical, and unmusical. Not to mention the fact that theatrical and cinematic education today trains an actor not as a thinker and an artist, but as a show-business employee.

From our premise about the philosophical and metaphysical dimension necessary to the theater, it follows that this meta-position enables one not merely to mimetically depict so-called life, but also to play a game. What does this mean? That, in all the experiments cited as exemplifying the fifth performative paradigm (the works of Marthaler, Vasiliev, Terzopoulos, and so forth), the theater ends up with exactly the event that has been jettisoned from life and has already become non-mundane, super-existential, excessive, and irremediable. Among such events thrown out of life in theatrical mythology, the stories of Oedipus and Orpheus are the most programmatic. Orpheus’s journey to Hades is therefore a metaphor, in a sense, for all truly theatrical action and theatrical processualism. The main event is that the hero has been forced to exit life, but also been forced to perform. (After all, when Orpheus loses Eurydice, he descends into repetition syndrome, “speechifying” and singing as the only way he can compensate for his loss.) Later, this same performance syndrome is acted out in the theater. That is, the tragedy of Orpheus has to do both with the loss of a loved one, and also with the fact that he is destined never to stop, constantly and syndromatically resuming his lamentations and mourning—a performance whose repetition is, in fact, the theater. The story is theatrical because its hero acts out grief, not because he is in grief. It is not merely someone’s grief that informs the theater and the actor’s craft, but the grief of only such a person who is able to play while being in grief. We thus obtain the formula for the performing of performing, the theater of theater.

Wasn’t this also Shakespeare’s mantra about the theater of theater? After all, only what proved to be theater in his life made it into his plays. Consequently, the theater played the theater. That is why Shakespeare’s claim that “all the world’s a stage” is no metaphor at all, but rather a statement of the fact there are realms of life that drop out of life into theatricality, and it is such realms that the theater repeats, reproduces, and adopts. Therefore, the real theater is theater about the theater, not in the modernist sense of “art about art,” but in the sense of theatrically performing what has proved more intense than life about life itself, of playing the part of life that has proved to be theatrical. This motif manifests in Yukhananov’s staging of Andrei Vishnevsky’s play Pinocchio (2019). Like Orpheus, Pinocchio goes on a journey through the inferno, because this is the only way he can find the beautiful Rose (Eurydice?). But this life journey proves to be a journey through the circles of the “theatrical” for the puppet (the actor, the poet). The theater is the place where the hero literally drops out of everyday life. And the only way to cope with this “theatrical” dropout from existence is with the theater’s help.

Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance, trans. Saskya Iris Jain (Routledge, 2004).

Hans-Thies Lehmann, Postdramatic Theatre, trans. Karen Jürs-Munby (Routledge, 2006).

André Lepecki, Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement (Routledge, 2006).

Florian Malzacher, “No Organum to Follow: Possibilities of Political Theatre Today,” in Not Just a Mirror: Looking for the Political Theater of Today, ed. Florian Malzacher (Alexander Verlag, 2015), 16–30.

The round table featuring Alexandra Konnikova took place on March 11, 2016, at the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre in Moscow → (in Russian).

Antonin Artaud, “An Affective Athleticism,” in The Theater and Its Double, trans. Victor Corti (Alma Classics, 2010), 93–99.

Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford University Press, 1997).

Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, trans. Mark Lester with Charles Stivale (Athlone Press, 1990), 149.

Yukhananov spoke about the inductivity of theatrical speech during his lecture at the NCCA in Moscow on April 26, 2016 → (in Russian).

Translated from the Russian by Thomas H. Campbell.