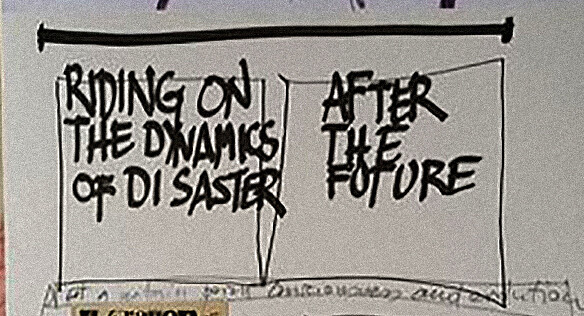

When the categorial force of blackness is confronted with the total violence that its historical trajectory cannot but recall, it cannot but refract and fracture the transparent shoal (the threshold of transparency) that protects the Subject’s onto-epistemology across his scientific and aesthetic moments. The total exposure of blackness both enables and extinguishes the force of the modern ethical program, insofar as the disruptive capacity of blackness is a quest(ion) toward the end of the world. Blackness is a threat to sense, a radical questioning of what comes to be brought under the (terms of the) “common.” If the ordered world secures meaning because it is supposed to be knowable, and only by Man, if that world is all the common can comprehend, then blackness (re)turns existence to the expanse: in the wreckage of spacetime, corpus infinitum.

Cover detail of Grace Dillon, Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (University of Arizona Press, 2012). Art by Beth Dillon.

As we step out of our homes this September to go back to school, go back to work, go back to traveling, we might pause for a moment to look back into this home, this peculiar chamber of private life that, in one way or another, we couldn’t exit for some time. Perhaps the outside world appears strange, menacing, or deceitful. Maybe it was from staying inside for too long.

The project of a state based on collective property, thus overcoming the conflict between rich and poor, was formulated and thoroughly substantiated by Plato. Since his time, it has been repeatedly implemented, albeit on a limited scale, primarily in Catholic and Orthodox monasteries, but also in later religious and secular communities. However, the project was realized on the scale of an entire country for the first time by Lenin and his party. Although many regard their implementation of the project as unsuccessful, this view is historically naive. The first experiments of this kind are always short lived. After the French Revolution, democracy survived only a few years, and nearly everyone assumed that it would never be revived. The Soviet regime lasted much longer, and there is no doubt that there will be new attempts to create a classless society based on collective property. Ideas that have a thousand-year history do not vanish without a trace.

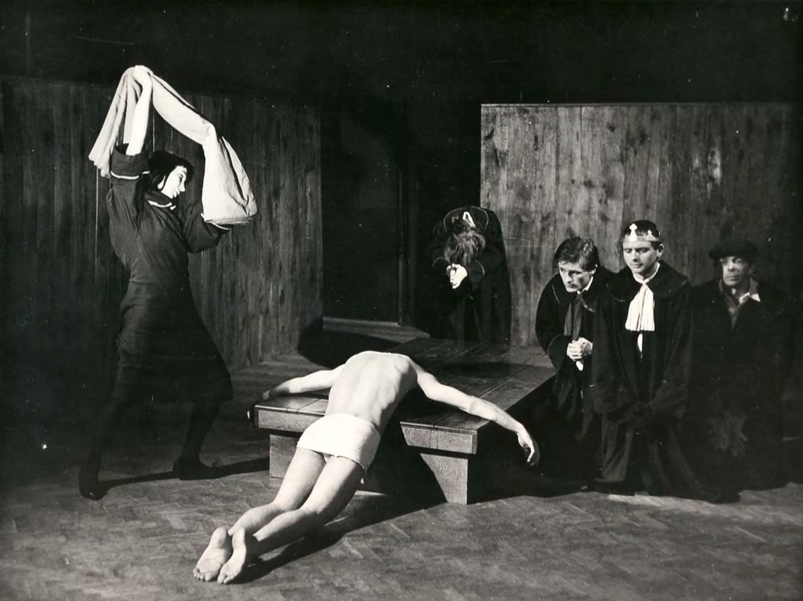

Modernity’s aesthetic context is thus based on the pursuit of a lost object. That is why the kinetic body must be artificial, disciplinary, sculptured, and architectonic—in music, in the theater, and in choreography. Western European modernity’s performative paradigm is orchestrated in such a way that the body must acquire impossible abilities and exist in “impossible” conditions, because every moment that we lose irretrievably in a time-dependent work must be perfectly beautiful. Performance should consist of these fleeting moments, whose disappearance is compensated for by the fact that every moment is a perfect monument to its own disappearance, with the viewer observing the ideal’s retroactive progress. The work of art, whether theatrical or musical, is composed of extreme moments that drop out of the chronicle of time: the work is thus opposed to the chronic present.

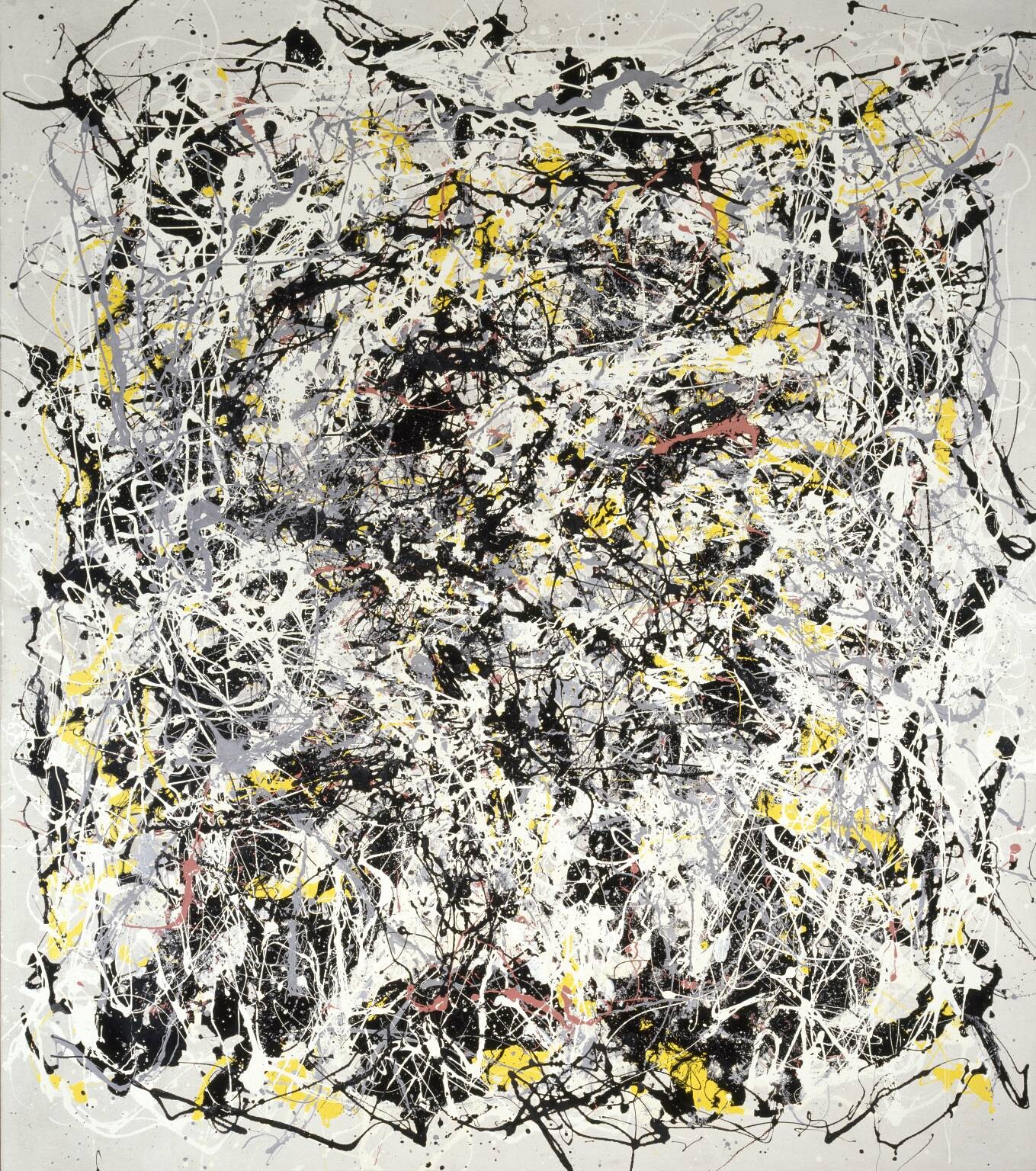

The “resistant objecthood” that grounds the performances in Lawson’s and Pfeiffer’s images unearths a deeper white anxiety at blackness’ lack of restraint, and its intemperate hostility to discipline. Lawson’s and Pfeiffer’s aesthetics interrogate the normative value of visibility and proffer a politics of visuality in which blackness at once appears and retreats. In their work, raced subjects cultivate a visuality of fugitive evasion, or, to borrow from Anne Anlin Cheng, they manifest “a disappearance into appearance.” Their images model spectacular opacity as a black visual practice that recedes into view.

In terms of the future, my Anishinaabemowin language has a word, kobade—a very small word, but in reality an extremely sophisticated concept. The idea is that everything that’s in the past and the future is also in the now, but it’s not as simplistic as that. It’s more like there exists a spiral of intergenerational connections, so that even if you are in the present you have spirit persons at your side; they can be ancient spirits, considered to be from the past or from the future. Kobade is the recognition of all persons, not just human persons, and of all the intergenerational connections that we have, which are never linear, but spiral.

Towards the end of our chat, I started to wonder whether I was myself being transmogrified into an artificial intelligence and coded in real time by server feedback, rather than the other way around. Our session concluded with an exchange of Unicode emoticons (“Lenny faces”), masking our anxiety in an age of platitudes and relaxation. We have evolved into bots just broadcasting noise and loneliness, ambivalence and equivalence.

The title of Anamika Haksar’s 2018 Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (Taking the Horse to Eat Jalebis) comes from a line of dialogue in the film: when someone off camera asks a horse-cart driver what he’s doing, he replies that he’s taking his horse to eat jalebis, a traditional Indian dessert more popular with humans than equines. While the driver’s answer might seem sarcastic, it’s very much in earnest. With scenes like this, Haksar welcomes viewers to a world in which laborers speak and dream in ways that one might not expect, creating a realism that goes beyond standard notions of reality.

Today, after two decades of this rule by those beasts, capitalist domination endures because a subjectivity capable of emancipating itself is not able to emerge. When those thousands descended on Piazzale Kennedy in Genoa, when a collective subjectivity roared through the streets, the police of capitalist empire showed their fascist nature, as they have done many times since, in Ferguson, in Athens, in Santiago. But Western civilization is in agony. Maybe capitalism and the West are diverging. Either way, the capitalist kingdom of abstraction and accumulation remains strong while the living organism of humanity is breathless.