Standing on the gates of hell, my services are found wanting. For I cannot give you what you want. What you want from me, here, on the gates of hell, is to open the gates and let you in. But I cannot do that. I don’t even see why that service should still be required. Because you have already passed the gates. You are inside. You live in contemporary hell. You inhabit the hell of the contemporary. And now you want me to perform the rite to confirm your passage? And give you reasons for being in there? I’m sorry, I can’t. To grant you a license to be where you are does not lie within my powers. Thus powerless I remain, standing on the gates of hell, observing what passes and sharing my observations with you.

Passing the gates of hell, you get everything you ever wanted. And everything you wanted is all you are ever going to get. Nothing more. Just that. Exactly what you wanted. Everything included. In hell. In a world to reflect your desires, a world coated in surfaces that fracture the light and make its reflections play across the skin of all things new in the modern world, the contemporary world: in a world that stays contemporary by rejuvenating itself in cycles of modernization, with each cycle eclipsing the previous one in accordance with the laws of planned obsolescence. To love this world you must forget all the new you got before, before you now became, again, the new you. The modern world has a lot to offer the new you; each cake it serves you is one to have and eat, so that always things can be had both ways: a trip to the moon and a journey through the unconscious, a holiday on foreign shores and a return home to a country you never knew, an innocence sweeter than raffinated sugar and a force brute enough to help you “claw yourself into an untouchable place.”1 All resources that the planet and its people provide—all the oil, spices, and metals, the power, sex, and money in the world—are at your disposal to fulfill the promise of transcending material needs through material means that modern culture, rendering itself contemporary over and over again, incessantly renews.

Remaining on the gates of hell, I will promise you none of this. I can only tell you there is more. No more of this. But much more than you have ever wanted before, or thought you deserved. For this too is modernism, of another, an always uncontemporary kind, a nagging doubt and a mocking voice, speaking softly, close to your ear: “What if there was something more to life? Than this? Something altogether different, something both/neither old and/nor new, something that was there for you, if only you had the guts to face it…” This is not my voice speaking. But another voice. I only relate what it says. Since I keep hearing it from where I stand, here, on the gates of hell.

No. 1. Uncontemporaries at the Gates

Standing on the gates of hell, I hear other voices. For I find myself in the company of others. In the company of my contemporaries. What makes them my contemporaries is their uncontemporary manners, their mannered ways of causing a disturbance at the gates, their insistence to not readily pass through the gates to enter the contemporary, without reservations. What brings us together, then, as uncontemporary contemporaries—or rather, contemporary uncontemporaries—is not a set of shared beliefs, not a joint endeavor, not a project or enterprise, but just this very intuition: that there is no reason to readily enter, but that it might be more wise to stay on the gates and take a good look.

Standing there, I find myself, for instance, in the company of Irit Rogoff, and I am with her when she writes that what makes us contemporaries is the act of looking at the problems of our time together and the realization that we share these problems—and maybe not much more apart from these problems—as we inhabit the condition of contemporaneity together. I agree with her in principle. I would contend, however, that facing today’s problems together as contemporaries, does not necessarily mean to “fully inhabit and live out contemporaneity.”2 I would rather say that the very act of facing the contemporary, as contemporaries, dissociates us from it—if only ever so slightly—just enough to get the space to take a look and take the time to have a word with each other. This dissociation is not an act of claiming distance, for there is no distance. How could there be any distance to the contemporary, when, as contemporaries, we live today, we are involved, we are entangled! Still, there is a difference in attitude. We do not enter the contemporary readily. We look at it, think about it, and talk about it. We make art about it. We generate philosophy, that is, to invoke the ghost of Nietzsche, a contemporary art of making unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen—uncontemporary observations. And we do many other things that demand neither education nor training, things done by all people who hesitate to readily enter (but never hesitate to respond to a distress call from anyone inside) contemporary hell.

Standing on the gates of hell, it is not out of hesitation that we do not readily cross them. Please, don’t assume that we are too fickle to make a leap of faith and enter! For this passing requires no leap. The passage through the gates, on the contrary, is a slow process. It is a matter of formalities and technicalities. It is a matter of finding investors, getting permits, and consulting specialists. This is how you enter hell in a contemporary fashion. Nowadays, it takes time, determination, and patience to go to hell. In these matters we can neither consult nor console you. The formalities and technicalities of the gradual passage to hell are not our field of expertise. We don’t pass; we leap. With leaps of thought, we jump from one point of view to the other in order to get a good look at the gates from different perspectives. If you want to picture the gathering of uncontemporary contemporaries on the gates, imagine a swarm of frogs, hopping and bopping around on its threshold. Leaps of thought are leaps of faith, almost by definition. For they presuppose and enact faith in the value of thinking, the value of a particular form of thinking: one that has no immediately realizable use value, that does not readily yield tangible results, that does not generate capital, the kind that you find in philosophy, art, and all forms of care. That value is not recognized inside the gates. So anyone who treasures the freedom of leaping like a frog, in terms of thought and faith, might be advised to stay hopping and bopping around on the gates.

No. 2. Facing the Gates

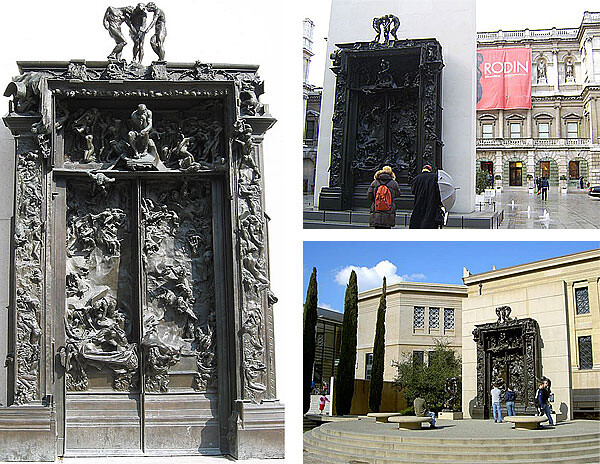

Standing on the gates I say, carefully avoiding the word “outside.” Because there is no outside. The whole world is contemporary. It continuously makes itself contemporary in waves upon waves of forceful modernization, of enforced modernization. But there is a limit to modernization, a liminal space to which to withdraw and address the contemporary world that modernization creates. This is the liminal space of artistic intellectual modernisms. It opens up on the limits of the contemporary world. Although it is not entirely outside, it is neither entirely inside the hell of the contemporary. It is un-contemporary in that it always borders on the contemporary, without ever becoming one with it. It is on the border. It is on the gates. Quite literally so. Look at Rodin’s gates. It is on the gates that the picture of life in hell materializes. Hell may itself be full of pictures. But the picture of hell as a whole can only be found on the doors. It is this picture that artistic intellectual modernisms have produced, time and again, on the face of the gates. The stuff of the face of the gates of hell is the material world that the contemporary uncontemporaries of modernity, artists and intellectuals, inhabit and emerge from.

Facing the gates of hell, I am amazed by the fact that there are still people here on the gates, and that somehow there always have been. For it must not be taken for granted that there should be any artists and intellectuals—or anyone else who cared, anyone with a heart and a mind—on the face of the gates, facing the gates. Neither is it a given that there is space on the gates. Such lives and spaces must first of all be created through a shared decision and a shared desire to describe, discuss, and remember the hell of the contemporary. It is through this shared decision and desire that the space of artistic intellectual discussion and remembrance opens up. To open up this space is to take a stance. It is to insist that what happens in hell should be exposed to view on the gates. It should not remain hidden behind closed doors. To insist that things should not remain hidden behind closed doors is to take a stance against the customs that govern life inside the gates of hell, the customs of claiming that nothing ever happened, when something did happen, so that business can quickly be continued, as usual. In defiance of these customs, artists and intellectuals insist that the memory, history, experience, and ramifications of life in hell are to be exposed to the public on the face of the doors. The liminal space on the gates of hell, the liminal space of artistic intellectual modernisms and all social forms of care, therefore, is a public space. The insistence on creating space on the gates is the insistence on there having to be a critical public.

No. 3. Weeping and Laughing

Facing the gates of hell, I now take a look around. I ask myself: Where am I? What place is this? This is not Paris. This is not America. Although it could be. This is another place. A particular place. Always another place. And always a particular place. This is because, throughout the last two centuries, various gates of hell have been built in particular places all around the world. And more gates are currently under construction. All these gates are portals to other gates. For all the gates of hell in the world are connected. They are connected through electrical wires, pipelines, and invisible flows of money. But they are also connected through shared ideas and shared feelings of joy and pain. Sometimes the laughter and weeping of people on one gate can be heard on all other gates too, as if the ones who laugh or weep were just on the other side. Upon hearing the sound, some people on the other gates won’t be able to help laughing or weeping as well.

Weeping and laughing on the gates of hell, I sense the passage that connects all gates to be a passage in space and time. It is the passage of modernity. It is one global modernity that links all of the gates. Still, each gate is different. Each gate is a pathway to a different modernity, one of many local modernities, one of many pathways to hell. What is shared from gate to gate through the weeping is the memory of all the disasters of modernity, each different, immeasurable, and beyond comparison, but all modern, all atrociously modern, following the cruel logic of the modern industrialized production of death and injustice. What is also shared through the laughter from gate to gate is the knowledge that the many promises of a better modern world to come were never met, and now seem more like jokes—absurd jokes, serious jokes, jokes that continue to contain a grain of truth. So as we weep today, it is not the end of modernity that we bemoan. Neither do we laugh about it dismissively. This is because the passing of modernity has not concluded. The industrialized production of disaster continues. And promises are still being made.

Weeping and laughing on the gates of hell, I do not feel particularly postmodernist. Postmodernism was neither particularly funny nor sad. We uncontemporary contemporaries, however, are particularly funny and sad. Because we have experienced the fact that history never ended. We have seen the unresolved tensions of modernity erupt in local conflicts, plunging modern countries around the globe back into hell. This is not over. It never was, and it doesn’t look like it will end anytime soon. Articulating our contemporary experience, we cannot therefore be anything other than uncontemporary. In our weeping we bemoan the disasters of the past that shape the present in order to try, maybe in vain, to prevent people in the future from repeating them. In our laughter we mock the promises of the past that have become jokes, to be entertained in the present and remind ourselves that, as long as there are still jokes to be made and people to make them, the future cannot possibly be as grim as it sometimes appears. This uncontemporary weeping and laughing, resonating between gates across the space and time of an unfinished modernity, is the weeping and laughter of contemporary art and thought.

Weeping and laughing on the gates of hell, listening and responding to the weeping and laughter of others, I am surprised to find that I quite often understand why they may weep or laugh. But then, often enough, I sadly do not. This is not because I lack information. It is rather because I sometimes simply cannot fathom what meaning means for people on another gate. Being raised on the gates of northern Protestantism, I was led to believe that to make meaning is to make things clear. This is what meaning means and this is how it is made. Everything is to be made clear. Because it can be made clear. This is quite a promise. Not that I would ever want to fully renounce it. It has potential. But by now it also makes me laugh. A lot. And weep quite a bit, too. Because acting under the assumption that this is what meaning means and that this is how it is made, I have severely misunderstood people on other gates. In the meantime, however, I may have learned one or two things by experiencing art and thinking on other gates. It seems that this is what sharing our experiences on the gates could be about: to grasp, through art and thinking, what meaning means and how meaning is made, on each gate and between them.

Sharing experiences on the gates of hell, we do then find ourselves performing some kind of service. We translate what meanings mean and how we experience experience into art and thought. This act of translation is also an act of historical codification. In art and thinking we find the historical codes for understanding what meaning will have meant and how experience will have been experienced. These codes are a key for understanding the joy and pain of life on the gates of hell now, in the past, and for the future. Similarly, these codes offer access to the logic of neurosis that governs life in hell. The logic of neurosis is always contemporary in that it governs our encounters today. It is also always uncontemporary in that the logic of neurosis doubles as the history of joy and pain, laughter and weeping, as it is inscribed in art and thinking. The service that we artists and intellectuals then find ourselves performing on the gates of hell is similar to that of a storyteller telling ghost stories to children. We tell ghost stories to avow the pain and joy of those who cannot find rest, because inside hell their pain and joy is not avowed. We tell the stories of the ghosts of the past to keep those ghosts alive in the present and give them a future in the memory of our children. We are not afraid of ghosts. The only thing we fear is for there to no longer be any ghosts. For if there are no ghosts, then there is no past and no future, and life on the gates of hell would cease to be possible. Without ghosts there would only be hell. So our service consists of the act of praying for ghosts. As we pray, we invent new incantations and learn historical ones from different gates. Standing on the gates of hell, we invoke each other’s ghosts and teach each other prayers.

Seance scene of a from the movie Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922) directed by Fritz Lang.

No. 4. Soul

Standing on the gates of hell, having stood here for a while now, I am forced to admit, once more, that no matter how hard I have tried—and God knows I have tried—my services are still found wanting. Not only can I not give you what you want, neither can I (nor will I) give you what you think you deserve. For getting what you think you deserve is just hell. Everybody in the end always gets what they think they deserve. And most people have already gotten it. But they don’t like to be reminded that they have. This is why hell is hell: People are afraid. The two biggest fears are: 1. To get something that one thought one didn’t deserve. 2. To then be forced to admit that one already had what one thought one deserved, and that it was bad. So if you want to charm the people in hell and give them what they want, the service you must provide is to relieve those fears. This is done through a simple trick. It is the secret of the trade of true liars: always only give people what they already have and think they deserve. But give it to them in a guise that allows them to rejoice in the illusion that they received something new, foreign, and exciting. This way you don’t scare people by offering more than they think they deserve. And you spare them the truth that they already had it all, and that it was bad, since you make the same old seem fresh, right, and justified. If you can perform this trick, you will be loved. For being the fake you are. But you won’t go to hell for that. Even if you think you deserve it and want it badly. Because hell won’t take you when the devil finds you out. You’ll be kicked right out of hell. And end up out here on the gates with us. Bad luck, buddy. Bad luck. So see you around, later.

Standing on the gates of hell, our services, therefore, are found wanting. For we insist on giving more than anyone thinks they deserve. Don’t ask me what “more” means. I don’t know. This is the point. This is why we linger and leap around on the gates: To talk about what more means, to talk more, think more, and make more art. For only one thing is certain out on the gates: life in hell won’t do. There must be more to life than this. A passage to unknown pleasures and a different state of mind. Or just one less lie. One lie less. Maybe it is that simple: As long as there are still people on the gates invested in the idea that there could be more, and therefore talking, thinking, creating more, there will be more. What for? And for whom? The question is justified. And in line with the faith in there being more than the obvious, it is simply not good enough for the answer to be that it’s all just for us, who happen to be invested in this idea. There must be more to this than just that. An uncontemporary proposal that modernist contemporaries have time and again made to gesture towards an answer and offer an alternative to hell on its gates was—not heaven—but the soul, the spirit of a world, or a ghost from a world that transcends the narrow horizon of the contemporary. I concede that this may just be another word for the divine, and therefore just an open gesture towards all that is more than just the given. But I like it for being that. As long as we still, or again, have open gestures to initiate a conversation, an exchange about what more we want, how to find more than what hell has to offer, we will continue talking, thinking, creating, and caring, here on the gates of hell. So my question to you is: What is the soul? What more can the soul be, the contemporary soul, the soul of the contemporary? How can we do things with a bit of soul? And create contemporary forms of thinking, making art and living together that have some soul? Because that would be much better than anything hell has to offer: thoughts and deeds with some soul. Franco Bifo Berardi writes that soul is the peculiar gravity that makes bodies “fall in with others.” So let’s leap and hop, eager and happy to see the many ways in which we drop in with others…3

No. 5. Happiness

Saying all this while standing on the gates of hell may make you think that I am a romantic. But I am not. Romance belongs to life in hell. Romance is exactly what people think they deserve. Nothing more than romance. Life in hell is fully romanticized. Each and every law that governs life in hell is put in place and held in place by romantic pictures and stories. Facing life in hell, standing on the gates, we see it all to clearly. Life in hell is unromanticizable. Because it is already fully romanticized. The last truly romantic act to perform is to acknowledge that life in hell has become impossible to romanticize, and to move on. To something more than just romance. To the love of the body, the love of the soul, and the love of its many ghosts. This is the ethics of an uncompromising dedication to the peculiar material being of others, encountered on the gates. A full dedication to their, your, our happiness. A happiness of the mind, the body, and the soul—and its ghosts. This is hedonism as radical ethics and philosophy proper. As a philosophy and art that becomes the sounding body for the laughter and weeping of many. A philosophy that creates laughter because it is a joke and consoles the weeping because it is a philosophy of tears, a philosophy in tears. This is an art and philosophy that is deeply romantic only in one respect: that it wants more than romance. Another form of happiness.

Standing on the gates hell, facing the gates of hell, laughing and weeping on the gates of hell, I summon you now, my uncontemporary contemporaries, because you have summoned me to come here, to address you. We summon each other all the time. This is how the public space to summon ourselves is created. The space and time to summon the ghosts, the most laughable and saddest ghosts of art and philosophy. This is not an end in itself. The end of the ceremony of summoning the ghosts of art and philosophy is the creation of the space of the public, the space of remembrance, discussion, laughter, and weeping—on the face of the gates facing the gates. Leaping around like frogs in this space on the gates, we recreate the faith in this space of art and philosophy through our mutual leaps. But this faith, as illusionary as it may seem, is a faith in there being more than just hell. A faith in there perhaps being a body and a soul, and something to share between bodies and souls, something more than we deserve and something more than hell will ever have to offer.

Shanghai, Fall 2009

I am indebted to Esperanza Rosales for explaining the U.S. to me using this expression.

Irit Rogoff, “Unfolding the Critical” (Berlin Tanzkongress, April 2006). See → (audio).

Franco Bifo Berardi, The Soul At Work (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2007), 9.