Of whom and of what are we contemporaries? What does it mean to be contemporary?

—Giorgio Agamben1

According to common-sense understanding, defining what we mean by the “contemporary” in art presents few problems: anything being produced in the present is always contemporary, and by the same token all art must necessarily have been contemporary at the time of its production and/or initial reception. This much is clear. It is also clear, however, that the phrase “contemporary art” has special currency today, as a commonplace of the media and of society in general. If “contemporary art” has largely replaced “modern art” in the public consciousness, then it is no doubt due in part to the term’s apparent simplicity, its self-evidence. Trouble-free outside the art world, the “contemporary” is twice as useful on the inside. For one, it appears to be a purely temporal marker, simply denoting the “now,” purged of critical or ideological presupposition. It appears not to require any lengthy unraveling, of the kind that Baudelaire, for example, felt to be required of the “modern,” whose sense of “the ephemeral, the contingent” linked an orientation towards the future to a break with traditional values, and in particular to a break with a cyclical conception of time.2

Renaud Auguste-Dormeuil, Guernica – April 25, 1937 – 23 : 59, 2005. Inkjet print mounted on aluminum and framed, 170 x 150 cm.

In his discussion of the word “revolution,” Göran Therborn has recently provided us with a striking indication of how this very shift from a cyclical conception of time to one of linearity and teleology took place in European thought:

Take the word “revolution,” for example. As a pre-modern concept it pointed backwards, “rolling back,” or to recurrent cyclical motions, as in Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, or in the French Enlightenment Encyclopédie, in which the main entry refers to clocks and clock-making. Only after 1789 did “revolution” become a door to the future…3

Ever since the querelle des Anciens et des Modernes at the end of the seventeenth century, the modern has been placed in explicit opposition to some other force, whether temporal or ideological. From the start, the modern was advocated, defended, set forth as a position among others. The contemporary, on the other hand, presents itself as something of a default category or a catch-all. Yet its success may not be altogether accidental; and if it is, it may nonetheless be entirely appropriate, if for somewhat more complex reasons. It may be precisely as a catch-all that it befits today’s field of artistic production more than ever, where—perhaps as a consequence of our collective disorientation—we have come to suspect modernity to be our antiquity; where the “Age of Manifestos” has long become the subject of our nostalgia—or not? Could there be a future for manifestos?

A “contemporary” manifesto could perhaps be perceived as a naïvely optimistic call for collective action, as we live in a time that is more atomized and has far fewer cohesive artistic movements. And yet there seems to be an urgent desire for a radical change that may allow us to propose a new situation, to name the beginning of the next possibility rather than just look backwards. In October 2008 this question was addressed in depth at “Manifesto Marathon,” a two-day “futurological congress” we organized in the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in Kensington Garden, London.4

With regard to the manifesto—and its current absence—as a piece of printed matter, Zak Kyes (who designed the book for Manifesto Marathon) on this occasion said:

The printed form of manifestos has always been inseparable from their radical agendas, which engage the act of publication and dissemination as sites for debate and exchange rather than mere documentation. For this reason, it is prescient to revisit the clarity and articulation—or, in many cases, willful obfuscation—of published manifestos today, a time which is defined by a panoply of publications as voluminous as they are homogenous… . For one thing is certain: without some kind of a manifesto, we cannot write alternatives that are more than vague utopias; without a manifesto, we cannot conceive the future.5

In his book Utopistics, looking at historical choices of the twenty-first century, the American sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein explored what could possibly be better—not perfect, but better—societies within the constraints of reality.6 As a mode of deployment, the manifesto requires an opposition for it to create such a rupture. We travel through dreams that were betrayed to a world system far surpassing the limits of the nineteenth-century paradigm of liberal capitalism.

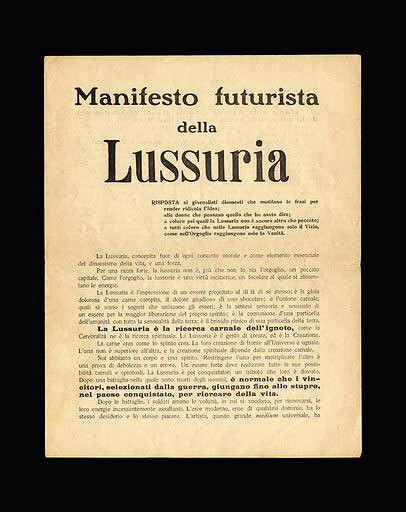

After all, the manifesto is a fundamentally transdisciplinary device, a history that is addressed in Martin Puchner’s recent publication, Poetry of the Revolution: Marx, Manifestos, and the Avant-Gardes.7 He breaks the history of manifestos down into three phases: first, the emergence of the manifesto as a recognizable political genre in the mid-nineteenth century (The Communist Manifesto, 1848); second, the creation of avant-garde movements through the explosion of art manifestos in the early twentieth century (Manifesto of Futurism, 1909); and third, the rivalry between the socialist manifesto and the avant-garde manifesto from the 1910s to the late 1960s. Fifty years later, it could be said that this rivalry has faded, along with the political opposition that fueled it. In the beginning, the art manifesto did not merely register art’s political ambitions; it changed the very nature of the artwork itself. “The result is … an art forged in the image of the manifesto: aggressive rather than introverted; screaming rather than reticent; collective rather than individual.”8 This has traditionally been the case for manifestos in the arts; however, it could be said that the twenty-first century art manifesto appears to be more introverted than aggressive, more reticent than screaming, and more individual than collective.

The striking commonality between artistic and political manifestos is their intention to trigger a collective rupture, and—like almost all manifestos in the past, which took the form of a group statement—assume the voice of some collective “we.” At the “Manifesto Marathon” event the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm observed this to be the case with all political manifestos he could think of: “They always speak in the plural and aim to win supporters (also in the plural).”9 Genuine groups of people, sometimes rallying around a person or a periodical, however short-lived, are conscious of what they are against and what they think they have in common—a history, Hobsbawm acknowledges, embedded in the last century. What now? Hobsbawm continued:

Of course, the trouble about any writings about the future: it is unknowable. We know what we don’t like about the present and why, which is why all manifestos are best at denunciation. As for the future, we only have the certainty that what we do will have unintended consequences.10

Echoing Hobsbawm, Tino Sehgal suggested a receptiveness to such unintended consequences to be a characteristic of the twenty-first century:

I thought the twenty-first century would be, hopefully, more like a dialogue, more like conversation, and maybe that in itself is a kind of manifestation or whatever. I am very careful in even using that word. I just think the twentieth century was so sure of itself, and I hope that the twenty-first century will be less sure. And part of that is to listen to what other people say and to enter into a dialogue, to not stand up and immediately declare one’s intent.11

But as Tom McCarthy pointed out on the same occasion, the certainty of the manifesto still lends it a certain charm:

What interests me about the manifesto is that it’s a defunct format. It belongs to the early twentieth century and its atmosphere of political and aesthetic upheaval. The bombast and aggression, the half-apocalyptic, half-utopian thrust, the earnestness—all the manifesto’s rhetorical devices seem anachronistic now. For that very reason it’s compelling, in the way a broken bicycle wheel was for Duchamp. Things that don’t work have great potential.12

And yet, it is the “unbuilt” or unfulfilled nature of the future that drives manifestos, and we can perhaps find some semblance of their utopian thrust and social imagination in projects that were for one reason or another unrealized. For every planned project that is carried out, hundreds of other proposals by artists, architects, designers, scientists, and other practitioners around the world stay unrealized and invisible to the public. Unlike unrealized architectural models and projects submitted for competitions, which are frequently published and discussed, public endeavors in the visual arts that are planned but not carried out ordinarily remain unnoticed or little known.

I see unrealized projects as the most important unreported stories in the art world. As Henri Bergson showed, actual realization is only one possibility surrounded by many others that merit close attention.13 There are many amazing unrealized projects out there, forgotten projects, misunderstood projects, lost projects, desk-drawer projects, realizable projects, poetic-utopian dream constructs, unrealizable projects, partially realized projects, censored projects, and so on. It seems urgent to remember certain roads not taken, and—in an active and dynamic, rather than nostalgic or melancholic way—transform some of them into propositions or possibilities for the future.

And here one encounters a paradox in the contemporary, just as the historicizing of modernism has itself been paradoxical: how can the ephemeral, the contingent, and the future be things of the past? For within the art world nowadays, the term “contemporary” does indeed most often assume a periodizing function, and such temporal markers always imply a before and an after. It is in this way that the “contemporary” presupposes more than it initially declares, and begins to approach a more specialized usage, one that may require nothing more than its repeated use within the ranks of the art world for its meaning to be apparent. But, with this repeated use, “contemporary art” loses its semblance of simplicity and begins to demand its own “before.” Of course, attempts to pinpoint a decisive historical break between the modernist and the contemporary are mostly stillborn and will lead to nothing but interminable wrangling. To give just one example, “the turn of the 1960s” will never do, just as the central claim of Fred Kaplan’s fascinating recent account of the year 1959—“the year everything changed,” as he puts it—should likewise be taken with a pinch of salt.14

What is it that makes the “contemporary” maybe worth rescuing from the charges I have outlined—of equivocation, default legitimacy, or just plain bad common sense? It may be what is perhaps most clearly seen in its use as a noun: the word “contemporary” implies a relation; one is a contemporary of another. The word “contemporary” is traceable to the Medieval Latin word, “contemporarius,” whose constituent parts “con” (“with”) and “temporarius” (“of time”) similarly point towards a relational meaning: “with/in time.” What is suggested here then, and what Baudelaire’s “modern” seems to disregard, is a plurality of temporalities across space, a plurality of experiences and pathways through modernity that continues to this day, and on a truly global scale.

The French historian Fernand Braudel describes how in the longue durée (long duration) there can be seismic shifts, like that which occurred in the sixteenth century as the center of power shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.15 We are now living through a period in which the center of gravity is transferring to new worlds. The second half of the twentieth century was very much a time of the “Westkunst,” to use the title of Kasper König and Laszlo Glozer’s groundbreaking exhibition.16 The early twenty-first century is witnessing the emergence of a multiplicity of new centers, above all in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Seoul, Tokyo, Mumbai, Delhi, Beirut, Tehran, and Cairo, to give a few examples. Since the 1990s, exhibitions have contributed considerably to this new cartography of art.

One great potential of the exhibition is to be a catalyst for different layers of input in the city. The multiplication of these events can be seen positively in terms of the multiplication of centers. The quest for the absolute center that dominated most of the twentieth century has opened up to include a plurality of centers in the twenty-first, and biennales are making an important contribution to this. They can also form a bridge between the local and the global. By definition, a bridge has two ends, and as the artist Huang Yong Ping recently pointed out: “Normally we think a person should have only one standpoint, but when you become a bridge you have to have two.”17 This bridge is always dangerous, but for Huang Yong Ping the notion of the bridge creates the possibility of opening up something new. The “contemporary” is thus spatiotemporal through and through.

In January–December 1993 as part of Museum in Progress, Alighiero e Boetti made a variation of his work Cieli ad alta quota in which six versions of the watercolor drawings were published in Austrian Airlines’ in-flight magazine Sky Lines.18 In addition, airline passengers could ask stewards for the same works in the form of jigsaw puzzles, which were the same size as the folding tables in the airplane. The six details of Cieli ad alta quota, which showed a certain number of airplanes flying within in a specific area in various directions, always implies the potential for expansion; continuing beyond the frame at both high and low altitudes. Destinations connect and interweave to form networks of lines along which meaning is created though the variety of possibilities for the migration of forms.

The impossibility of capturing form in Boetti’s Cieli ad alta quota takes us to Giorgio Agamben’s “What Is the Contemporary?” which shows the one who belongs to his or her own time to be the one who does not coincide perfectly with it—to capture one’s moment is to be able to perceive in the darkness of the present this light which tries to join us and cannot: “the contemporary is the person who perceives the darkness of his time as something that concerns him, as something that never ceases to engage him.”19

Defining contemporaneity as precisely “that relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism,” he goes on to describe this contemporary figure as the one who is not blinded by the lights of his or her time or century: “The contemporary is he who firmly holds his gaze on his own time so as to perceive not its light, but rather its darkness.”20 Agamben takes us to astrophysics to explain the darkness in the sky to be the light that travels to us at full speed, but which cannot reach us, as the galaxies from which it originates recede faster than the speed of light. To discern the potentialities that constantly escape the definition of the present is to understand the contemporary moment.

Jean Rouch often told me about the immense courage required in order to be contemporary, to engage in the difficult negotiation between the past and the future. Like Agamben, he spoke of a means of accessing the present moment through some form of archaeology. Both Rouch and Agamben agree that being contemporary means to return to a present we have never been to, to resist the homogenization of time through ruptures and discontinuities. Agamben concludes:

This means that the contemporary is not only the one who, perceiving the darkness of the present, grasps a light that can never reach its destiny; he is also the one who, dividing and interpolating time, is capable of transforming it and putting it in relation with other times. He is able to read history in unforeseen ways, to “cite it” according to a necessity that does not arise in any way from his will, but from an exigency to which he cannot not respond. It is as if this invisible light that is the darkness of the present cast its shadow on the past, so that the past, touched by this shadow, acquired the ability to respond to the darkness of the now.21

Giorgio Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?” in What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press, 2009), 53.

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, 2nd ed., trans. and ed. Johnathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1995), 13.

Göran Therborn, From Marxism to Post-Marxism? (London: Verso, 2008), 129.

Taking place on October 18 and 19, 2008, “Manifesto Marathon: Manifestos for the 21st Century” was the third in the Serpentine Gallery’s series of marathon events, and addressed the question of how to develop manifestos at a time when fewer artists work in formal groups and there are significantly fewer artistic movements than in the past century. Hans Ulrich Obrist invented the interview marathon concept in Stuttgart in 2005 as an experimental kind of public event that bridges panel discussion, exhibition, and performance. In 2006 the concept evolved as Rem Koolhaas joined Obrist in interviewing over seventy people in a twenty-four hour marathon that took place in the Serpentine Gallery’s summer pavilion, co-designed by Koolhaas and structural designer Cecil Balmond. The pavilion was one of an ongoing series of annual architecture commissions conceived by Serpentine director Julia Peyton-Jones. The 2006 marathon was followed by the Experiment Marathon with Olafur Eliasson in 2007, the 2008 Manifesto Marathon, and, last but not least, the Poetry Marathon in 2009. In December 2009 Obrist and Koolhaas engaged the rapidly growing city of Shenzhen with “Shenzhen Marathon: The Chinese Thinking.”

Zak Kyes at “Manifesto Marathon,” October 18, 2008.

Immanuel Wallerstein, Utopistics: Or, Historical Choices of the Twenty-First Century (New York: The New Press, 1998).

Martin Puchner, Poetry of the Revolution: Marx, Manifestos, and the Avant-Gardes (Princeton University Press, 2006).

Ibid., 6.

Eric Hobsbawm, at “Manifesto Marathon,” October 19, 2008.

Ibid.

Tino Sehgal, at “Manifesto Marathon,” October 19, 2008.

Tom McCarthy, at “Manifesto Marathon,” October 18, 2008.

See Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution (New York: Dover, 1998 [1911]).

See Fred Kaplan, 1959: The Year Everything Changed (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2009).

See Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, vol. 2, trans. Siân Reynolds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

“Westkunst,” Museen der Stadt Köln, Cologne, West Germany, May 30–August 16, 1981.

Huang Yong Ping in conversation with Rohini Malik and Gavin Jantjes, trans. Hou Hanru, Fondation Cartier, Paris, March 8, 1997, →.

The Exhibition “Cieli ad alta quota” was curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist for Museum in Progress and Austrian Airlines. See →.

Agamben, 45.

Ibid., 41, 44.

Ibid., 53.