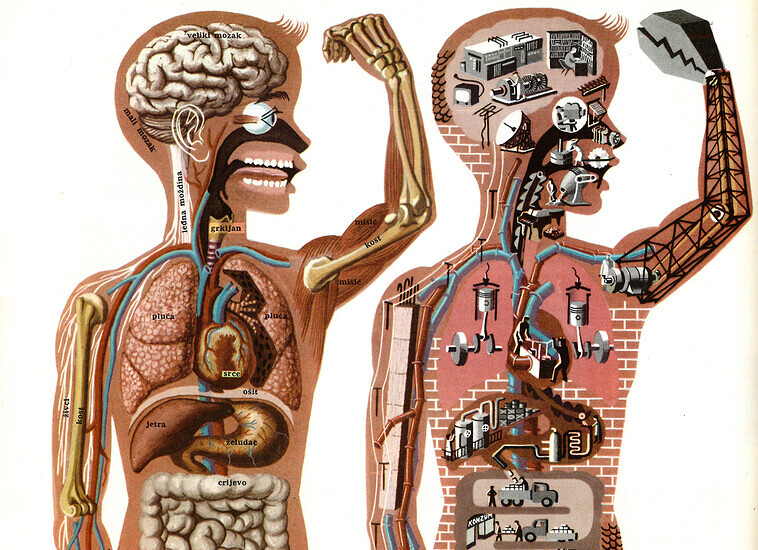

For more than a half century, the Yugoslav collective body performed enormous ideological and metabolic work, and became exhausted. Rescued from the dustbin of history, it was turned into an “ur” collective body that neoliberal capitalism and the twenty-first century tore limb from limb—dismembering the collective body. Everyone took a piece—museums, galleries, archives, books. Where that collective body once stood is now an empty stage—which also means that new beginnings are possible. How can we build our collective body anew?

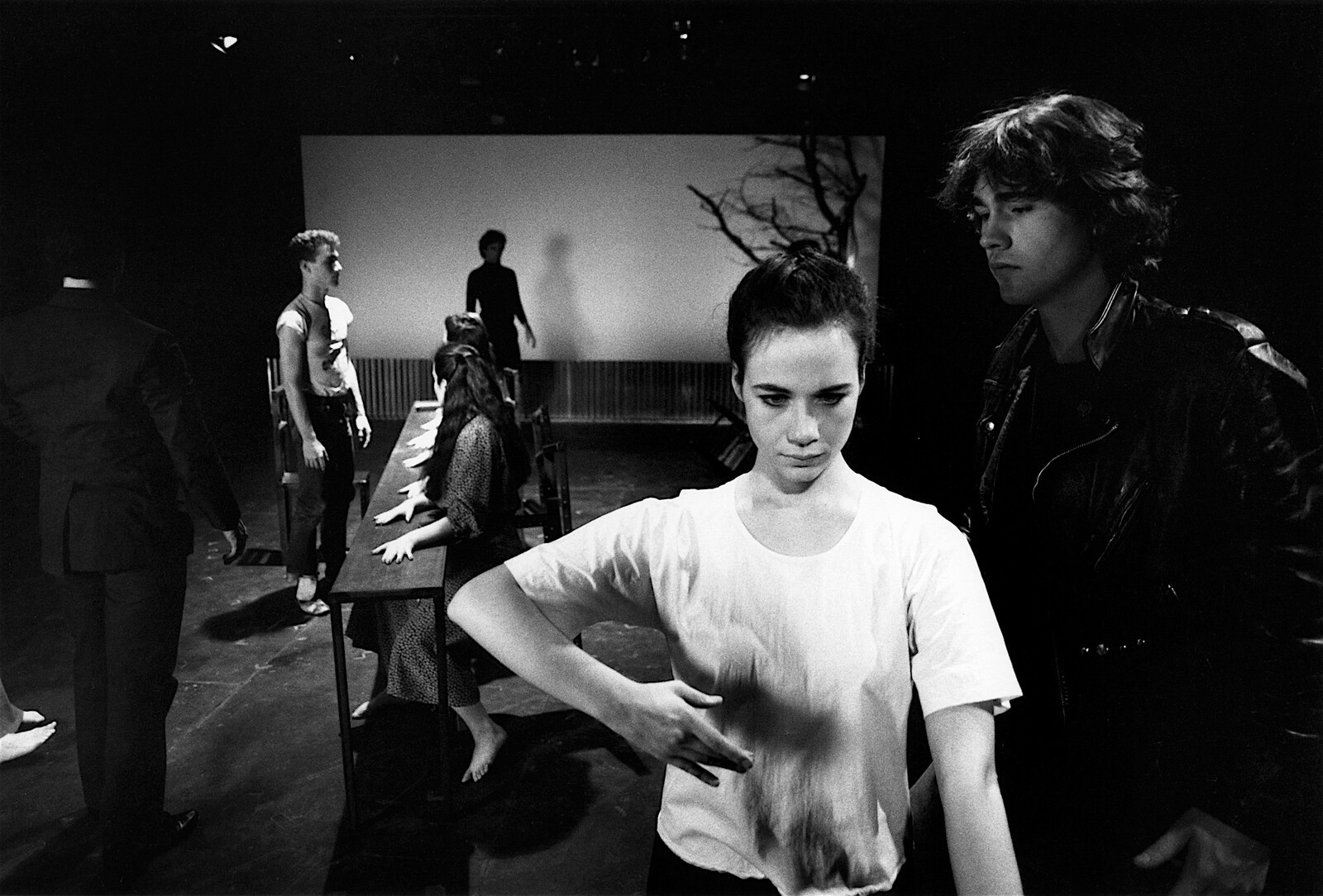

Marta Popivoda, Yugoslavia: How Ideology Moved Our Collective Body (still), 2013. Documentary, 61 minutes.

The Covid-19 pandemic has attacked not only our individual bodies, but our collective body as well. Through thirteen contributions by writers who are mostly from former socialist countries where the space of freedom is contracting once again, this special issue of e-flux journal asks what this collective body actually means, and what it has become.

How to create a community within the arena of biopower without killing off the individual? How to create a collective, and not some zombifying crowdedness, while living in a democracy that is currently being transformed into a discursive category debated at conferences? How to create a body, a Hamletian body that will stand against and redefine the imposed lie of capitalism, of injustice?

With the industrial revolution, curing and caring for oneself took an individualist turn: it became a private affair for the privileged. Self-care was turned into a sign of cultural sophistication for the Western imperialist class.

Covid-19 probably has its own ratholes, which our society tries to block with the help of protective masks and sanitizers. If recent psychotherapeutic treatment for OCD aims at correcting the symptoms of the disease, the task of Freud’s psychoanalysis was to find its cause. Freud’s rat is a medium, biting through the walls the boy tried to hide his desire behind, breaking through the cordon sanitaire of his misplaced affections. A rathole is a break, a crack in a disciplinary blockade.

I propose that we view the autoimmune condition both as a medical diagnosis and a heuristic, periodizing device, whose etiological impasse encapsulates the symptoms of the planetary crises of today, and at the same time activates a mounting pressure, and desire, to overcome them.

The bodies that filled the streets of Polish towns and cities in the fall of 2020 created transversal connections and grassroots institutions. Artists were part of this great creative collective too. In particular, their work supported the communication strategies of the protests.

Omuz is a new solidarity network in Turkey that came into existence shortly after the worldwide lockdowns in early spring 2020. A few days after the first Covid case was “officially” announced in Turkey, a small group of art professionals began seeking financial support for art practitioners who lost their secondary jobs, which had been their primary sources of income.

Is there a need for a Roma museum of contemporary art? Who would shape its collections, and according to what criteria? Is it possible to avoid the traps of stereotypical representation? How would such a collection represent the civil rights and emancipatory struggles of the Roma people, along with the historical and present-day contexts of these efforts?

Nothing makes more sense today than to revamp the social imaginary of our collective body. That body is in danger. It is under attack by other species. It is wounded. Its immunity has to be built. It has to be taken care of. It should heal. And it can only heal collectively. At the same time, nothing seems less probable.

Considering the unprecedented existential threats posed by climate change, the scarcity of resources, and the ever-increasing number of forcefully displaced people that at this point have surpassed eighty million worldwide, we must ask ourselves which type of future heritage we want to build today. Is the T-shelter really the best we can offer to protect the bodies of displaced people in the present and in the future?

It has become abundantly clear how “politically correct” discourse and the sensibilities of so-called “cancel culture” have become tools of the art-system hierarchy, enhancing an image of museums’ self-doubt and self-reflection. As much writing by contemporary activists and theorists of black liberation show, this is only a cosmetic reaction.

We need to learn from trees and forests. We need to practice a politics of solidarity with nonhumans. Without this understanding, the only common ground that humans and nonhumans will have is a planetary future without us.

The image of clusters of trees frozen in time, disconnected from their former environment, could not be more appropriate as a metaphor for how advanced desertification is engulfing our collective soul and draining its sap.