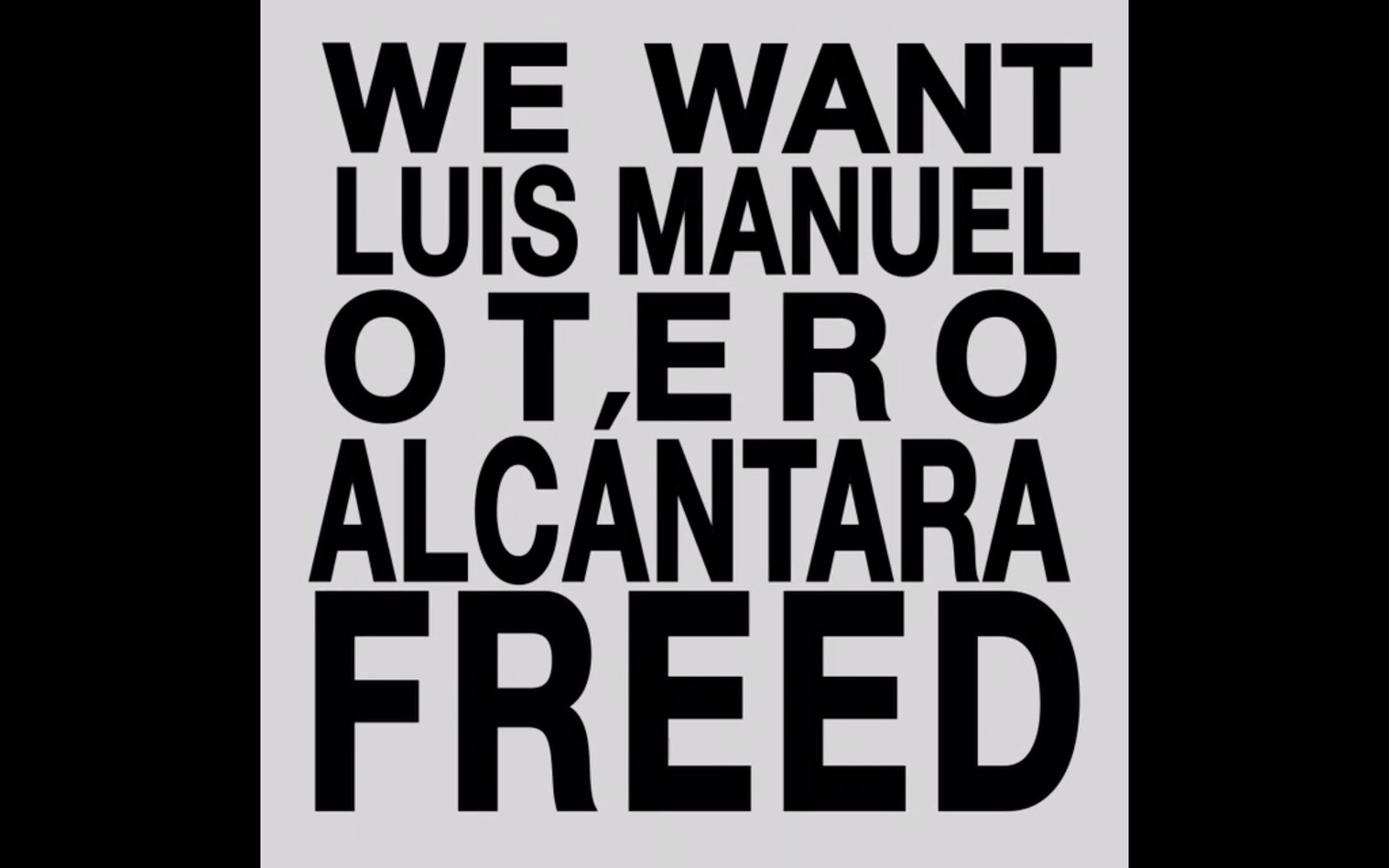

There is a Black artist in Cuba who has turned his own struggle with state authorities into a media spectacle that dramatizes the situation of his people. His work points to the contradictions between his society’s purported ideals and the governing elite’s ruthless pursuit of total power and wealth. He has been thrown in jail dozens of times, and tens of thousands of Cubans around the world follow him online. He is self-taught and of humble origins. He lives in a poor neighborhood in Old Havana, not far from the luxury hotels that tourists flock to so they can visit Cuba “before it changes.” The artist’s name is Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara. He has no work in MoMA’s collection, he hasn’t been invited to a Venice Biennial or even recognized by the Black Lives Matter movement, but he’s the best-known artist in his homeland right now. He’s also public enemy #1. His government has done everything they can to stamp out his influence, short of killing him. Right now, he is in a hospital under police guard, and he might very well be dying.

Throughout 2020 and 2021, Cuba has been convulsed with protests staged by artists, dissidents, LGBTQ and animal rights activists, disgruntled farmers, indignant doctors, and regular folks that are angry about police brutality and food shortages. This fact has barely caught the attention of international observers. It’s hard to compete for the (first) world’s attention when the global pandemic still looms large, the US capital was recently overrun by domestic insurrectionists, Israel is bombing Gaza again, and mass protests are going on in Colombia, Myanmar, and Russia. It’s also hard to get around the prevailing fixation on a mythical view of the Cuban revolution as anti-imperialism’s last stand, and to overcome foreigners’ morbid curiosity about an island that some believe to be frozen in time. Those of us that live in countries where it’s legal to take the streets sometimes forget that despite the tropicalist flamboyance of its popular culture, Cuba still bans protests and opposition political parties. Artivism, social practice, social engagement, and public art, the principal tactics employed by do-gooders of the art world, are all treated as criminal acts when carried out without state approval on the island, as is citizen journalism. The government just announced that it will also seek to try Cubans in absentia if they engage in such activities abroad. My publishing this piece probably means I won’t be going to Cuba any time soon.

Cuban activists and journalists often lament their government’s strategy of subjecting its opponents to a slow death via police harassment, short-term detentions, house arrests, disrupted telecommunications, invasive surveillance, expulsion from state organizations, and defamatory campaigns on state media. Those methods, together with the strong business ties between European investors and GAESA (the Cuban’s military’s tourism conglomerate), as well as the US trade embargo that serves as the Cuban government’s convenient excuse for everything it does and doesn’t do, help to keep the international outcry about the country’s human rights record to a minimum. On top of all this, the Cuban government’s blanket rejection of its critics as mercenaries promoting US interests is widely accepted in the country’s progressive circles. Foreign journalists frequently insinuate that all Cubans who publish in outlets subsidized by American grants are politically suspect, despite the fact that journalists in most authoritarian states and developing countries depend on foreign subsidies. The singular focus on American support distorts a true understanding of how independent cultural endeavor is carried out in Cuba. Many of the most prominent Cuban independent media outlets are financed by European foundations and Cuban private investors in the diaspora. Cuban exiles are the principal source of economic support for islanders who use the internet to transmit their complaints. Even those independent publications that do receive aid from US State Department-subsidized entities such as CIMA (the journalism division of the National Endowment for Democracy) assert that they are not subject to editorial control by their funders. There was a time during the Cold War when the US government was intent on overthrowing the Cuban government and exile hardliners advocated violence, but those days are past. The Cuban diaspora is far more politically diverse than it is given credit for, and the billions of dollars that it sends annually to relatives in Cuba sustain the very system that so many have chosen to leave.

While state repression has prompted many Cubans to flee the country over the last six decades, the scale and intensity of government attacks on artists and intellectuals have greatly intensified since 2018. During that same year, Cubans gained access to the internet on cell phones, which empowered them to share information with each other and with the rest of the world in real time. This explosion of criticality in the digital realm has put the Cuban government—which is unaccustomed to dialoguing with its citizenry—on the defensive. It also shattered the state’s hegemonic control over its public image at home and abroad at a time when its economy is in tatters. Nonetheless, the Cuban government’s criminalization of dissent is far less newsworthy than televised executions or aerial attacks on civilians, which are more likely generate international outrage. Whether that outrage would lead to action is an open question, especially for the art world, a sector of society that has become very adept at calling out its villains and praying for its embattled heroes, but that still resists taking a political stand against the policies and practices of governments. One could attribute that reluctance to the individualism of its practitioners or restrictions against political advocacy imposed on American non-profits, but it would be naïve to ignore the fact that the art market benefits from its relative lack of state regulation, and also that keeping silent about government excesses is precisely what allows the commercial operations of the art world to remain unchecked.

Otero Alcántara, who has become the figurehead of Cuba’s recent protests, has been sequestered in a Havana hospital for nineteen days. Cuban state security agents forcibly removed him from his home on the eighth day of a hunger and thirst strike he had undertaken to protest police seizure of his artworks in mid-April. At first, the Cuban government issued statements suggesting that he had faked his hunger strike, even though Otero Alcántara had appeared seriously weakened in live chats from his home. Shortly thereafter, the government changed its story and claimed that Otero Alcántara was “being treated” and imbibing fluids. A few days later, state media claimed that the Cuban medical personnel were adhering to the 1991 World Medical Assembly Declaration of Malta on Hunger Strikers, which suggests that Otero Alcántara has continued or resumed his hunger strike and that the hospital staff is not force-feeding him. Speculation abounds as to what “treatment” he may be receiving; official pronouncements are so vague and contradictory. Since his arrival at Calixto Garcia Hospital on May 2, the artist has been under twenty-four-hour police guard and has remained incommunicado via his own channels. Friends attempting to visit him have been detained by police that surround the hospital, and the few relatives who are permitted short visits refuse to speak to the press.

The Cuban government has released four rather strange videos of Otero Alcántara: the first, broadcast on state television shortly after his apprehension, showed the artist walking into the hospital, already dressed in a hospital gown. The second, which was posted to his physician’s Facebook page, shows him sitting on his bed next to the doctor, who speaks to the camera most of the time. The physician only allows the artist to affirm that his medical treatment has been “spectacular.” The third video, issued a few days later, shows the artist walking around the hospital parking lot with the same doctor. Otero Alcántara was evidently not free to speak in any of the videos. He is not able to take calls on a hospital phone. I have never heard of a physician in any hospital in the world taking the time to make cell phone videos with patients or escort a patient on a tour of hospital grounds, so these communiques strike me as very odd. The fourth video, posted to Facebook on May 19, is the most macabre of all: Otero Alcántara is visibly thinner and debilitated, speaks somewhat incoherently, and asks for his mother, who died in January, 2021. A tray of food, which he only picks at once, sits on his lap. An uncle who appears in the video with him tells him he was called out of work to come to the hospital, which suggests that the recording was produced at the behest of the authorities. The entire exchange is awkward, and the video is crudely edited. It would be difficult not to conclude that the public is being fed propaganda.

Otero Alcántara is co-founder of the San Isidro Movement, a group of artists, poets, musicians, and activists who have gained notoriety since 2018 thanks to their savvy use of social media and advocacy for expanded civil liberties. He has been detained by police over fifty times since 2019, subject to frequent and prolonged house arrests, and is vilified on Cuban state media, accused of being a lackey for the US government. The hunger strike he launched with several others in November 2020 to protest the arrest and summary judgement of a colleague led to a violent police raid on his home, which was broadcast via Facebook Live and sparked the largest public protest from the Cuban cultural sector in decades. That protest on November 27, 2020, which saw hundreds of Cuban artists and intellectuals gathering outside the Ministry of Culture for over twelve hours to demand a meeting with officials, led to the formation of the 27N movement, another network of artists and independent journalists that advocates for expanded civil liberties for all Cuban citizens.

The main differences between 27N and the San Isidro Movement are not ideological but sociological. 27N members, mostly graduates of the University of the Arts and the University of Havana, hail from Cuba’s cultural elite. Among the San Isidro Movement’s members are many self-taught rappers, spoken word poets, and visual artists, the majority of whom are Black. Both groups have several members that have lost jobs in state institutions, and in some cases the right to commercialize their art, because of their outspoken political views. Otero Alcántara and rapper Maykel Osorbo were featured in the music video Patria y Vida (which translates to fatherland and life, a retort to Fidel’s famous phrase, “fatherland and death!”), which was released in February of this year. The song was composed and performed by six Black Cuban musicians from the island and the diaspora, including Grammy Award winners Descemer Bueno and Yotuel Romero. The video garnered 5 million views on YouTube in three months, and quickly became the oppositional anthem of Cubans worldwide. The phrase has been painted on walls throughout the island, and Cubans have taken to singing the song to protest police that arbitrarily arrest citizens.

During the ransacking of Otero Alcántra’s work this spring, the police also arrested the artist, who was performing in his apartment on a garrote chair. The same weekend, the Cuban Communist Party met for its Eighth Congress, and Raul Castro stepped down to much foreign fanfare. One of the artist’s neighbors made a video of the raid that circulated widely on the internet, prompting an outpouring of rage on social media against the government for its treatment of Otero Alcántara. A street protest in support of the artist on April 30 led to the arrest of ten Cubans, including the independent journalist who transmitted coverage of police attacking the protesters on Facebook Live. None of those who were arrested have been heard from since. Just three days ago, San Isidro Movement members and musicians Maykel Osorbo and Elexer Funk were picked up by Cuban police—Osorbo was in his apartment at the time and was arrested shirtless and shoeless. Elexer Funk was released the following day, but there has been no sign of Osorbo. Meanwhile, the most recognizable members of the 27N movement—artist Tania Bruguera, poet Katherine Bisquet, and journalist Luz Escobar, among others—have been subject to prolonged house arrests and intermittent telecommunications interruptions, as have San Isidro Movement members Amaury Pacheco and Iris Ruiz. It appears that the Cuban government is banking on its ability to make its latest public relations headache invisible while it waits for the Biden administration to resume bilateral negotiations.

Locking up Otero Alcántara in a hospital, especially a Cuban hospital, generates widespread confusion abroad. We are not accustomed to thinking of modern-day hospitals as agents of state repression. The exaggerated claims about the island’s healthcare system are not only spread by the Cuban government. They are also propagated by Michael Moore’s documentary Sicko, the celebratory press coverage of the Cuban medical missions dispatched to Italy at the height of the COVID 19 pandemic, and the latest news about Cuba having already sold its untested Covid-19 vaccines to Iran. Taken together, these function as distractions that divert attention from the actually precarious conditions in Cuban hospitals, widespread medicine shortages, and the lawsuits filed by Cuban doctors against a division of the World Health Organization for participating—along with the Cuban government—in human trafficking and forced labor of medical personnel.

Otero Alcántara’s friends and followers have good reason to worry about the nature of the medical treatment he is receiving. Cuba has a history of using medical interventions punitively against dissidents. Afro-Cuban filmmaker Nicolásito Guillén was jailed and institutionalized repeatedly between 1970 and 1989, during which time he received multiple electro-shocks. Prior to his “treatments,” he made an experimental film in which the song Fool on the Hill played over an image of Fidel Castro. Afro-Cuban intellectual Walterio Carbonell was sent to a labor camp for six years and committed to a psychiatric hospital in the 1970s after trying to present a “Black Manifesto” to the Ministry of Culture along with several colleagues. That history, together with extensive testimony from former Cuban political prisoners about the use of sodium pentothal on inmates, as well as several leaks from anonymous hospital staff about the militarization of the hospital and the ways the artist is being treated, have led to a sounding of the alarm.

Although recent Cuban protests have been small in comparison to uprisings elsewhere, they mark a seismic shift for islanders and the diaspora. Cuban government officials clearly know this, which explains why they are reacting so defensively against nonviolent protesters.

Foreign interest in Cuba remains dominated by the myth of a revolutionary utopia. That vision of Cuba, however dear it may be to progressive idealists, has caused great harm by confusing the idea of the revolution with the reality of Cubans’ experience. It’s time for foreigners to let it go and remember that Black lives matter in Cuba, too.

—May 21, 2021