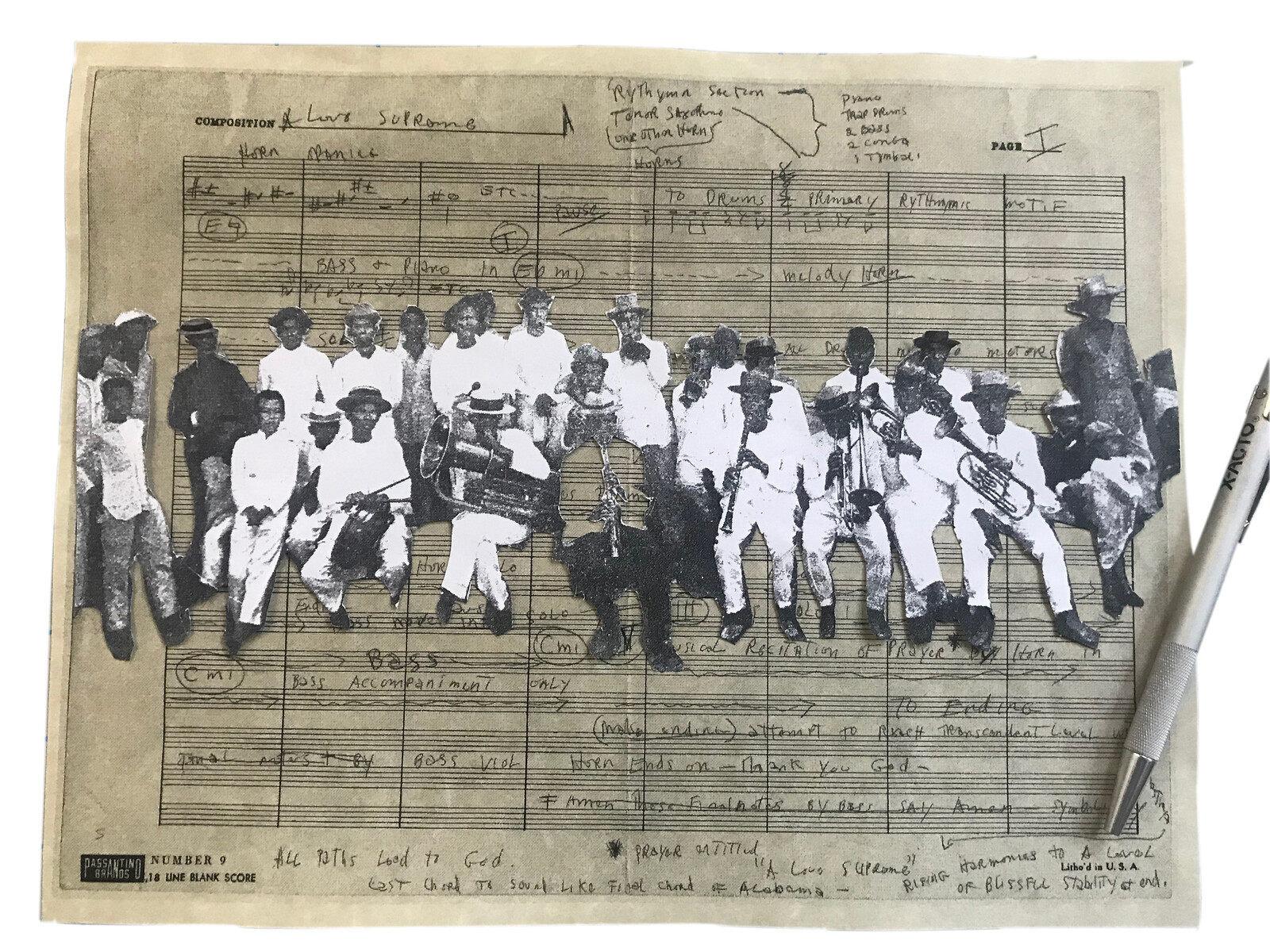

Editor’s note: Images and captions are the author’s own, from his book Atang: An Altar for Listening to the Beginning of the World (Quili-Quili Power Press, 2021). A full description of the experimental book project, along with a free e-book download, can be found at the author’s website →.

Lubong

At the height of making many of the drawings and collages that would become part of this book, late summer 2020, smack dab in the pandemic, I woke up in the middle of the night with a ringing in my left ear. I have pretty heavy tinnitus from all those years of dancing and DJing in clubs and bars, but this was extra loud.

A lot of folks have a ringing in their ears that comes and goes. My tinnitus is always there, a mix of hissing and very high, very faraway singing. I’ve woken up some nights and thought I was hearing a chorus of children a block away. If you could hear the beginning of a toothache, turned the volume down to about 2.5, and made it sustain from the moment you woke up to the moment you dozed off, my tinnitus is a bit like that. It’s like foil shaking. No. It’s like hundreds of thousands of bits of foil shaking in the air around my ears. It’s a stratosphere of mosquitos or a million hummingbirds blacking out the sky.

My tinnitus has changed my hearing enough that I forget exactly what bells sound like. I can hear them. But I know I don’t hear them the same way most other people hear them. I know I don’t hear them the way I used to hear them. Small bells especially.

Mary Rose asks me if my hearing is precious now. She asks if I’m scared that I’ll lose all my hearing. And I say no. I mean, yes, I’m scared, but no, I’m accepting how my world will change. It already has.

That night last August, I managed to get back to sleep for a little while before waking again around dawn. The ringing wasn’t just stronger than usual, it sounded like I was underwater. I got out of bed and made some coffee, thinking it was just a particularly long swell of my tinnitus, which happens occasionally. Sometimes the wave of ringing lasts as long as 10 or 15 minutes. So I took my hot cup, sat on a chair by our front window to quietly start my day.

It was close to 7am. We live on a wide residential artery with downtown just a block and a half east. The first commuter of the morning drove past. And it froze me. The engine, the rumble of the tires against the road were all muffled, as if they were far away. And whatever clarity of the sound I was processing was coming only from my right ear. I waited for another car. And not a minute later, the same. I couldn’t tell which direction the cars were coming from. They may as well have been doing donuts under my nose. Then two cars drove by. I shoved my finger in my right ear and listened as more cars passed. It sounded like somebody had taken a speaker, knocked it on its back, and was holding it down with pillows and cushions. I could barely hear anything.

***

I’ve spent the last ten years or so learning how to talk to the dead. I feel a little funny saying this because I’m still pretty deeply American in sensibility, but I’d be lying if I pretended otherwise. My cousins who were born in the Philippines don’t think talking to the dead is weird at all. They do it all the time. They tell me about the visits the dead make, not just in dreams but in the bodies of birds and spiders and butterflies. They tell me their mom—my Auntie Uding—visits. Our grandparents visit. My mom visits, too. They sometimes have messages of warning or comfort. Sometimes they come just to make us laugh. It has happened to several of us that the dead come to tickle our feet to scare the shit out of us. And then we, the living, can talk about the visit to someone who understands. And we, the living, can laugh really hard together. And I imagine the dead are still around when we’re laughing. I imagine that’s why the dead come to scare us in the middle of the night with such a feathery touch. The ones who have no choice to leave a body might understand the body best. They crack up at our stubborn unfamiliarity with death.

I’d gotten good enough at listening to the dead that I could call them in. Not like they’d come every time I called, but time to time they’d come. And that’s how I’d heard stories from men and women who lived in other times and places. Ancestors. Not long ago. Some of them in California, during the twenties and thirties. Some of them had worked with my grandfather in Hawai’i before picking lettuce in the Pajaro Valley. Some of them were living in Watsonville when Fermin Tobera was shot in his sleep. One elder told me how they had kite-making contests, each man trying to better the other in style. Some of them drawing pictures on their kites of cars or angels. Some of the manongs writing the names of a sweetheart or inscribing a little wish in the corner. And then they’d run out like boys all the way past the dunes to the water and they’d test their kites out, some of their slapdash inventions smashing into the sandy hillocks, some snagged in the trees, and others flying way up.

A picture of Perfecto Bandalan and Esther Schmick appeared in the Watsonville newspaper in December 1929. The image of this Filipino and a white girl embracing riled racial anxieties barely a month before The Palm Beach Club dancehall was set to open at the edge of town.

On January 20, 1930, posses of local men formed to hunt Filipinos down. They were assaulted throughout Watsonville. Some of those manongs were thrown off the Pajaro River Bridge. One posse arrived with weapons on the Murphy Ranch to stand outside one of the bunkhouses where the laborers lived. One of the white men shot the bunkhouse up. And Fermin Tobera was killed in his sleep. Sometimes I’m asking questions that the dead won’t answer. And I have to see it for myself. And I think, there were no fine suits or hand-crafted shoes. No half-finished letters to family back in Pangasinan. Probably no kites hanging from the ceiling. There probably wasn’t a guitar. The men responsible for Tobera’s death were tried and let go. That is neither speculation nor a dream of the dead.

Those men were field laborers—and dancers, so in their visits they gave me stories of making music with nothing but a tabletop and a stolen guitar, these men holding each other close in a bunkhouse before they got all dressed up in their fine suits with a pocket full of dimes. No matter how exhausted, bruised, or sore, they dug down deep into the reserves to shave, clean up, and head to the dancehall. No matter—in California, in 1929—that it could cost them their job or their lives.

***

I’ve mostly played guitar and keys throughout my life. And a few years ago, I started playing percussion. I practiced every day, before and after work, in between phone calls. I quietly worked on rhythms and rudiments on my lap at meetings, in the slow-moving traffic of I-676, on my walks to the laundromat, testing all the syncopated subdivisions, studying time. I listened to records and more records. I watched videos of Tata Güines, Angá Díaz, Ray Barretto, Johnny Rivero, Jerry Gonzalez, Raul Rekow. Mary Rose tells me I fall asleep tapping on her thigh or wrist and sometimes the drumming starts again in the middle of the night. I hear a rhythm in rock and roll or jazz or experimental electronic music and it’s calling out to Bantú songs or Abakuá or bembé. Sometimes I hear the gangsa of the Kalinga or the plosives of the ipu. Sometimes I hear the rhythm of the song my dad used to sing to my baby brother to help him shit—takkiiiiiiii, takki! The more I studied, the more closely I listened, the more I remembered.

I love percussion (and just playing music in general) because touch is a part of the listening. What most people don’t realize is that when they’re listening to music, they are listening to someone’s listening. And so much of a musician’s listening happens through touch. I believe having a “feel” for the music is about a kind of unnamed sense, one in which all the available physical senses heighten and converge to make meaning—before language, before thought, a nearly simultaneous electricity and chemistry in the blood and in the neurons and in the bones.

In the film Sound of Metal, Riz Ahmed plays Ruben, a drummer who loses his hearing. His character goes to school with hearing disabled children to learn how to be deaf. And there’s a scene where Ruben, the children, and the teacher are gathered around a man playing classical music on a grand piano. And they all have their hands on the body of the instrument. And I know that feeling. I feel it through the keys when I play piano. I’ve put my hands on a piano when my father was playing and these days when my wife plays. I don’t just feel it in my fingers and palms. I can feel it in my chest, and if I’m still enough I can feel it in my scalp and the bottoms of my feet.

***

I was trying to keep my mind off the uncertainty of my hearing. My left ear still felt walled in when Mary Rose and I tuned into a live conversation about the Hō kū leʻ a, a Polynesian vessel whose construction became both a symbol and materialization of the genius of Native Hawaiian maritime seafaring. Overhead, our ceiling fan was spinning, letting out a squeaky pulse. I’d joked for months that it’s my metronome while I practice rudiments on drums.

The Hō kū leʻ a isn’t just built in Polynesian tradition, it is navigated with traditional Polynesian wayfinding techniques—no Western technology. Kā lepa Baybayan, who has served as captain of the Hō kū leʻ a, was talking about the star compass, or using the altitudes of celestial bodies to orient their boat on the sea. They find their way by something called dead reckoning. He explains further that even when they’re sleeping they can tell by the sound and the feel of the waves that they’re off course. “Our compass is visual, yeah? It’s also based upon feeling and internalizing the movement of the canoe. There’s a certain beat and rhythm the canoe makes as you’re sailing on the ocean on an extended course. You internalize the motion. If the motion changes, if the pulse changes, then two things have either happened. Either the environmental conditions have changed or you’ve gone off course. More likely, you’ve gone off course,” Kā lepa says.

And then mid-sentence, the regular squeaking of the fan fell apart. The sound started breaking up like crazy. It started multiplying. The window was open. I realized it wasn’t the fan, which I could still hear. I stopped the video and turned my head toward our front yard. It was geese. I could hear the geese, honking around the same pitch as our fan. It was one of those cool days in late summer. I’d just told Mary Rose this feels like autumn weather. And the honking of the geese outside, the overlapping rhythms—they must have been right overhead. It was all mixing with the squeak of the ceiling fan. The cat let out a soft meow in the kitchen, too. Hungry probably. And it all belongs. All the sounds belong together—the geese, the fan, the cat in the kitchen, and now somewhere in the overcast gulls were yucking near the same pitch as the geese. I was weeping then. My hearing had been changed for a long time. I was just traveling deeper into a world I’d already been living in.

***

The dead are always with us. You hear me? Maybe they do come to give us insight or knowledge. But they also come to lead us astray. And somewhere in the ghastly tapestry of wisdom and trick, prank and sagacity, the dead remind us that our bodies are theirs. Not just our ears and hands. Not just the belly and the spine and eyes. But the heart and lung and muscle. It’s how we hear them. You feel me? It’s how we listen. The dead carry the past, all the listening of their past, all the solitude of their listening, all the gathering of their solitude. They carry the past of their past. And we carry the dead.

We have an entire body for carrying. We have an entire body for listening. They’re playing their guitars. They’re crafting their kites. They’re scribbling their names, their wishes. They’re drawing a bird, a boat, a cross. They’re hanging the kites from the rafters of a bunkhouse, from the ceiling of a dancehall, from the beams of a bombed out house. They are bidding one another farewell by smashing the glasses against the walls. They are holding each other tight in the dark. They’re kissing someone’s hair in the dark. They’re listening for the waves in the dark to find their way in the sea. They’re plucking the flies from the rice bin and sifting the moths from the flour. Listen. They’re counting the gulls. They’re spitting into a cup full of blood. They’re birthing our grandfathers. Listen now. Listen. They’re holding each other’s hands as they weep. They’re ringing their bells and so are the dead of the dead of the dead, which is to say their sounds are so old. So very, very old. Their sounds are our sounds. Listen. Their listening is our listening. Everywhere in our bodies is the end of our lives. Everywhere in our bodies is the beginning of time.

Awan

And what can I do about it Nothing I can’t do anything I can wring my hands or look out at the rain coming down for hours now until the streets fill up Even when there’s nothing there’s something you can’t see And what can I do now that everything I do is invisible I can’t even see its legs any more that thing galloping now west carrying the sun on its back screaming for the murderers to exit their houses to use the front door to announce themselves We know you’re in there You have nowhere to go You can do nothing There’s nothing to do Move along Move along Nothing to see here even if you shine a light on it Even if you set the whole city on fire Look at the bells I mean listen to them They’re as good as rain filling the neighborhood breaking into windows Men have dreamed of machines to travel as fast as them clap in the heavens all the Zeus-like engineers looking into the stratosphere seeing nothing Nothing at all just like what’s haunting us just like what’s jailing us just like what’s keeping us on track in line on point Radar of the gods Come in Come in No response nothing Where is God the child asked after the towers fell Where is God God is everywhere If you think long enough about his location you arrive by logic not at his whereabouts but his substance which is nothing God is nothing Not even murder Not even mercy Not even the fly crawling out of the crow’s mouth Even when the bird is talking he’s not saying nothing Not a goddamned thing Not even the weight of a hatchet Not even the hole you dig to bury it Not even the ancient trees he’d trouble himself to reap until the whole hillside’s blank Nothing Nothing there No branches No leaves Not even a flimsy twig to hang your hat or a log to which you can nail your feet

A Study of Beauty

To have rejected strategy; to sit, instead, with one’s bafflement; to see such bafflement as a preface to madness—and awe; to touch some simplicity, to attend to that simplicity; to relentlessly pursue its continuity with the infinite; to catch the occasional glimpse & be changed. Not sparkling embellishments or pristine blades. Not the effete disguised in denim. Not the FOR SALE sign hanging from the Gallery of Misery. Not the policies of lawncare, but the bulbous deformation of one green gourd borne on a dying vine. Not the gloss of museum marble, but the young man weeping under the vaulted cobwebs. Not deputies of the spreadsheet, but a road disappeared under new snow. Not scripted tours or curated wonders, but the crack that runs the length of the last drinking glass in the cabinet. Not surveillance, but surrender. Not worship, but devotion. Blessing and blasphemy, both. Not the sanitized tables of slaughter, but the fleck of tendon that pops the butcher in the eye.

Buneng

Some things I’m learning as I start to cut. Collage is so much like DJing and making music—the kinds of care in the tight spots, finding the relationships, the places where one thing meets the next, the illusion of seamlessness, the intention of the cut, the suture, the healing, the little song I make up in my head while I’m cutting, the absolute surrender to the utterly local without giving up on the flow of the whole.

And like two pieces of music, sometimes the material is disagreeable: the knife won’t go where you thought it would; the slice isn’t clean; I can ruin hours of work with one slip; I have to forget how dangerous the blade is. It’s teaching me patience which means it is teaching me about time, how to be so inside of it, I’m outside. I once heard the leader of a rumba group drumming in the park yell at the salidor player, “You got to lose yourself to find yourself, man!” This art does not let me forget: I am an agent of ruin, destruction even, and there are only a few art forms that do this. I’m learning, in order to collage, I have to cut away. I have to choose to lose (and often it’s not even my choice) and I’m using a knife to do it. But I know the history of the knife. Machete, cutlass, bolo, and in my parents’ language buneng. To chop down grass for a roof, to slaughter an animal for feast, to wield in the face of another soldier.

I’m talking to the knife. I’m talking to the paper. I’m talking to the dancers and the king. Cutting them away from their context makes them more alive. Some of them are hard to remove from their context. I’m thinking of relationships in ways that are both familiar as a writer and a musician and in other ways that feel like total expansion. What I really mean is that the accidents are new. I’m prone in a brand new way. I’m staring down into these photos and drawings and I’m looking into heaven at the same time. Prone to heaven. Prone to hell.

On the Lateness of Filipinos

Flavor is a function of time

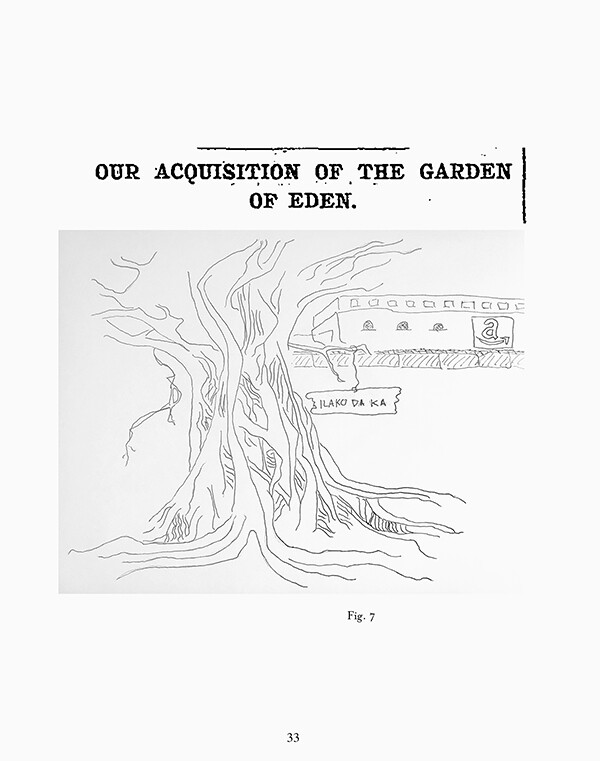

This headline was published in the New York Times on February 15, 1901. America thought that they found the Garden of Eden, which is to say that America believed it was returning paradise to its rightful stewards. I thought this was a joke but nah they really believed that. I wanted to learn how to draw a balite tree. So there’s that.

Tabas

To read beyond one’s style is both a temperament and a skill. To read beyond one’s

style is a style itself.

Tabas

To severely restrict oneself to a given style is also a style. That style is an anti-style.

It is the death of a style. It is a mortuary of style.

Trabaho

To be the one to make the ropes they use to hang the man

and

to be the man they’ll hang.

Lung-aw

Art doesn’t change you. Attention changes you. Art is one version of attention. Art without soulful attention is public relations. Pornography.

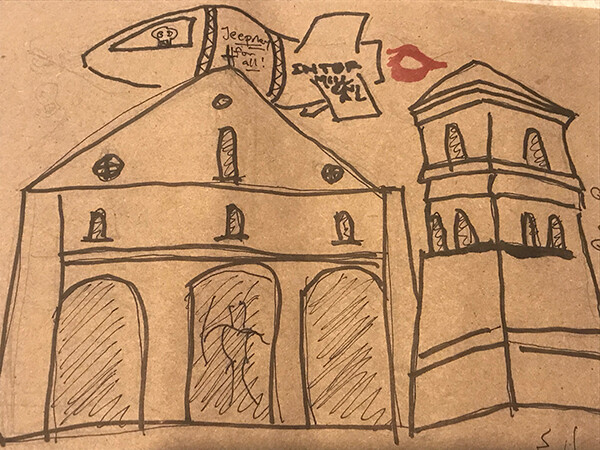

I started doing these bigger drawings on butcher paper with my students in an improvisation class in fall 2019 that met for six hours on Saturdays. We fed each other food and just hung out, talking about art and language and poetry. And then we did a lot of these drawings together, finally inviting the community to join us in a massive drawing on butcher paper about water. Maybe I’ll make another book and talk about that. Anyway, these drawings were all kind of visual improvisations about the Philippines and Spain and dancing. I like the spaceship and I never drew a Filipino church before. And check out the Callao figure came back to dance in the vestibule!

Pen and pencil drawing of an angel. Looks like a superhero. I wish I could draw good enough to make a comic book. My brothers can!

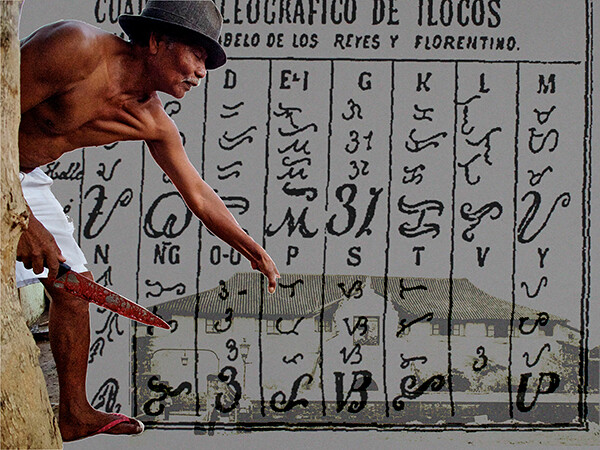

That’s my Uncle Charlie with real blood from a goat he was slaughtering for a little party we were having. And that’s the Ilocano alphabet from a page in the de los Reyes book. Also, that’s Fort Santiago in Manila that the Spanish built.

These are some of my nieces and nephews in Barangay 41, Santo Tomás, Laoag City, Ilocos Norte, Philippines. A day or two before I left, one of the kids came up to me in my uncle’s yard and they were like, “Tito, ammom ti agaramid ti ullaw?” And I was like, “Ullaw?” What is that? They tried to explain but I couldn’t get it. So they scattered. One brings a walis tinging (a broom made of thin sticks, which are the spines of a palm tree leaf). Another kid grabs a plastic bag. And another comes down the dirt road with what looks like VHS tape pulled out of the cassette. And they all gathered around and started making this thing. And it was a kite! It was amazing! I show this to improvisation students when we get together. I don’t know if they’re actually impressed. But I am!