1.

Why did Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) and Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948) never meet?1 It may seem like an odd question, but there’s a reason behind asking such a thing. Benjamin visited Moscow in the winter of 1926 and stayed for two months. He didn’t see Eisenstein, but did get to see his “old teacher” Vsevolod Meyerhold.

At least three other people were critical links in the chain that connected these two outstanding figures who shared an ideology and orientation during a turbulent century. The first is Asja Lacis, the “Russian woman” who made Benjamin travel all the way to Moscow, and the second is Sergei Tretyakov, a colleague of Eisenstein and a key figure of the Soviet avant-garde. Bertolt Brecht is the third person who brought these two together. Lacis introduced Benjamin to Brecht, and Tretyakov was Brecht’s closest “Russian friend.” We do not know if Tretyakov met Benjamin in person, but at the very least there is evidence that he influenced Benjamin’s essay “The Author as Producer.”

Tretyakov visited Germany for a lecture tour in 1931 and stayed there for six months, during which time he quickly became acquainted with Brecht. In an interview with a Swedish paper in 1934, the same year when Tretyakov published the translation of Brecht’s work on epic theater, Brecht said, “In Russia there’s one man who’s working along the right lines, Tretyakov; a play like Roar, China shows him to have found quite new means of expression.” Just a year before Benjamin released “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin spends the entire first half of “The Author as Producer,” written while in exile in Paris, on Tretyakov.2

DVD cover of Sergei Eisenstein’s movie Battleship Potemkin. Kino Classics Series, Blu-ray edition, 2005.

Naturally, Eisenstein and Brecht met several times and knew each other’s work well. Eisenstein first met Brecht in Germany in 1929. Their mutual acquaintance, Edmund Meisel, was the music director for the German release of Battleship Potemkin and also the music director for Brecht’s Man Equals Man (1926). Eisenstein and Brecht took the train back to Moscow together in 1932, and crucially, in 1935, they saw a performance in Moscow by Chinese actor Mei Lan-fan. The now famous term “alienation effect” (Verfremdungseffekt) first appeared in Brecht’s review of this performance, and in fact, Brecht had met Viktor Shklovsky, the founder of the concept of “defamiliarization” (ostranenie) in Moscow in 1932. Tretyakov, then a secretary of the international section of the Writers Union and committee member of the Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, introduced the two at that time and also arranged Mei Lan-fan’s performance tour that visited Moscow.3

Meanwhile, Tretyakov and Eisenstein first met at the Meyerhold Theater in 1922. As colleagues and proletkult activists, they continued to collaborate on a number of films, including the intertitles for Battleship Potemkin. Tretyakov acted as Chinese correspondent for Pravda while also teaching Russian literature at Beijing University, and Eisenstein once planned to produce a series of educational films on China based on a Tretyakov screenplay. Tretyakov may have even sat between Eisenstein and Brecht (alongside Meyerhold) during Mei Lang-fan’s performance.

Mei Lan-fan as Kuei-Ying and Wang Shao-Lou as Hesiano En in Chi’ing Ting Chio from the Chinese Theater. Copyright: Villa La Pietra NYU Florence.

Eisenstein’s travel route and range of associations spanned beyond Europe to include the United States and Mexico.4 Benjamin’s intellectual activity also went beyond Berlin, continuing in Moscow and Paris. But the two lives never intersected. Eisenstein never mentioned or cited Benjamin, but it is not rare to find Benjamin referring to Eisenstein. By the time Benjamin visited Moscow in the winter of 1926 for the ostensible purpose of writing the Goethe entry for the Soviet Encyclopedia—but in fact to see Asja—Eisenstein was already a celebrity all over Europe. Benjamin watched Battleship Potemkin in Moscow, which was released in Germany that year with considerable buzz, and immediately wrote a short review of the film.5

The general assessment of the review, titled “Reply to Oscar A. H. Schmitz,” is that the ideas in it evolved into his famous 1935 essay. In the review, for example, Benjamin puts forth an argument that was quite unusual at the time: “The vital, fundamental advances in art are a matter neither of new content nor of new forms—the technological revolution takes precedence over both.”6 The phrase below, which speaks of the “the dynamite of [the cinema’s] fractions of a second” that exploded the “prison-world,” survived both the second and third editions of the essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”:

We may truly say that with film a new realm of consciousness comes into being … In themselves these offices, furnished rooms, saloons, big-city streets, stations, and factories are ugly, incomprehensible, and hopelessly sad. Or rather, they were and seemed to be, until the advent of film. The cinema then exploded this entire prison-world with the dynamite of its fractions of a second, so that now we can take extended journeys of adventure between their widely scattered ruins.7

As is immediately clear in the oft-cited passage above, the position of seeing cinema as a special “arsenal of perception” that can awaken revolutionary potential is a sure link between Benjamin’s film (or media) theory and Eisenstein. For example, there is a self-explanatory intersection between the “shock effect” of Eisenstein’s montage, represented by “attraction,” and Benjamin’s key points of “shock” and “distraction.”8

The problem is that connecting the two figures through the link of cinematic perception has many limitations. Both figures and their concerns aimed beyond “art” and toward “history.” For both of them, cinema (and its study) was only a contemporary version of a larger “fundamental problem” (Grundproblem). The two thought “through” cinema, and it is necessary to find their intersection on a broader horizon “outside” cinema.

The two figures shared a characteristic way of thinking: “a construction of history that looks backward, rather than forward.”9 In other words, instead of looking at the future based on the present, this way of thinking intends to see and reveal the present through the past. To make possible the emergence of a counter-history by unearthing “the prehistoric or archaic” once buried and distorted in a history written by convention is what composes the core of Benjamin’s “dialectical image.” Not unlike Benjamin, who insisted that the real task lies in “turn[ing] our backs to the future and fac[ing] the past,” Eisenstein, who attempted to expand the problem of cinema to address the fundamental law of creating art, or the intrinsic structure of human thought (“primitive thinking”), was also taken up by the historical-philosophical implications of looking to the past.

In the following text I attempt a comparative reading of two great contemporaries, focusing on one intersection that demonstrates their shared ways of thinking. This intersection is the mythology of the “glass house.” The cultural genealogy of the glass house is one of the most interesting chapters of both twentieth-century intellectual history and the history of art in general. A peculiar characteristic of this genealogy, which proceeded through a variety of changes from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, is its development across different regions and media. The mythology of the glass house, which originated in England, formed a unique “constellation” that not only encompassed culturally specific narratives and models from France, Germany, and Russia, but also brought together the spheres of art, architecture, philosophy, and ideology.

This story marks an important turning point in the ideological evolution of both Benjamin and Eisenstein.

Film still from Fritz Lang’s movie Metropolis (1927).

2.

In the late 1920s, Eisenstein was working on three projects with utopian overtones. The first of these “unrealized projects” was his attempt to cinematize Karl Marx’s Capital using James Joyce’s method.10 The second was to write a “spherical book” with the aim of changing the whole terrain of film theory, and the third was The Glass House project.

Eisenstein first came up with the idea for The Glass House when he visited Germany in 1926. At the premiere of Battleship Potemkin in Berlin, he was introduced to a number of German artists and filmmakers, including Fritz Lang. The stage set of Metropolis (1927) and the glass dome that was installed there left quite an impression on him.

Eisenstein planned to film The Glass House in the United States. It was the very first project he proposed to Paramount Studios when he came to Hollywood and signed a contract with Jesse Lasky. His idea evolved into an architectural image of American society, that is, a symbolic vision of social hierarchy in capitalism. In this way, Eisenstein’s perception of Germany (Metropolis) became merged with the image of America, which we might infer from his referring to the project both by its English (Glass House) and German (Glashous) titles in his notes.

Charlie Chaplin, whom he met in the United States, supported the idea, and Le Corbusier, who visited Moscow in the fall of 1928, is also known to have expressed enthusiasm for it.11 In fact, the discussion in Hollywood reached such a stage of specificity that it was even decided to use a factory in Pittsburgh to produce the glass structure for the film. However, like many other Hollywood projects, this plan remained only “on paper.” The original outline continued to change, the project became endlessly delayed, the plot was revised many times, and in the end it was never brought to completion.

The concept of glass architecture has a long and complex genealogy. A holistic view of its development, which passes through all sorts of intellectual and artistic movements of twentieth-century Europe, is not an easy task, but at least there is a consensus as to where this genealogy should begin.

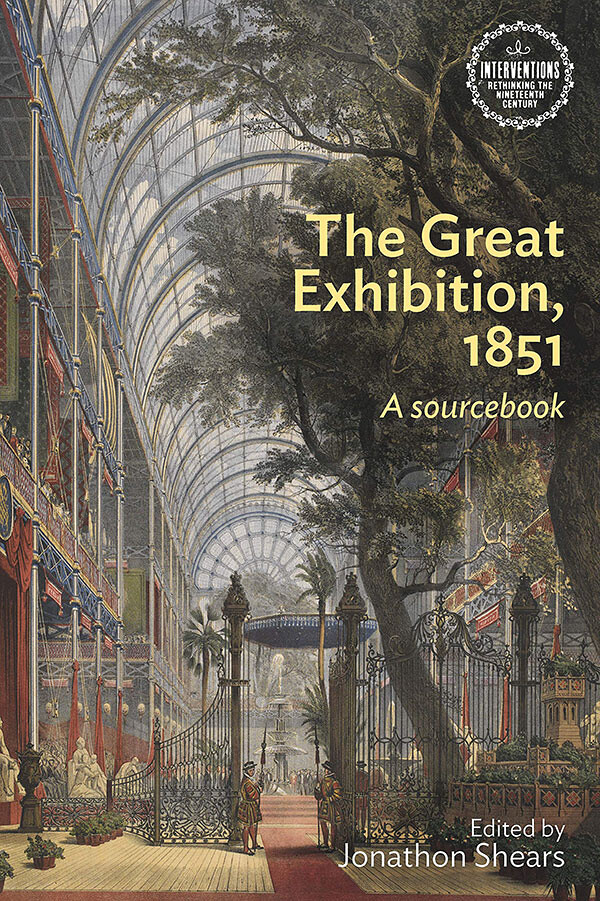

The “Great Exhibition” first opened in London on May 1, 1851. In this “festival of liberation,” which Benjamin called a place of “pilgrimage to the commodity fetish,” the center of attention was undoubtedly the massive structure built in Hyde Park using only iron and glass.12 The Crystal Palace was not only the largest building of its era; it was also constructed in the shortest amount of time.13

The Paris arcades of the late 1820s are generally regarded as the first instance of the large-scale use of glass panels in urban architecture. World’s fairs often featured structures that were essentially expansions of these “passages.” According to Benjamin, “World exhibitions glorify the exchange value of the commodity” and “open a phantasmagoria which a person enters in order to be distracted.”14 In other words, they were an embodiment of what Marx once called the “theological niceties” of the commodity: “A commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties” (Capital, vol. 1, chap. 1, sec. 4). Agamben noted that Marx was actually living in England when the first fairs were held. Presuming that Marx’s famous commodity fetish chapter was based on his impressions of the Crystal Palace, Agamben summarized that at the heart of that impression was “a prophecy of the spectacle, or, rather, the nightmare, in which the nineteenth century dreamed the twentieth.”15

Cover of The Great Exhibition, 1851: A Sourcebook (2017) by Jonathan Shears.

Strictly speaking, this is an upside-down version of the utopian dream surrounding the Crystal Palace, which was the origin of the cultural myths surrounding glass architecture. More than anything else, contemporaries perceived the building as a “giant greenhouse.” Designed by the landscape architect Joseph Paxton, who worked as the head gardener for the Duke of Devonshire, this large greenhouse contained a garden, statues, a fountain, and palm trees. The Crystal Palace looked, according to German art historian Julius Lessing, like “all that we imagined from old fairy tales of princesses in a glass casket, of queens and elves who lived in crystal houses.”16

Paradoxically, Russia, one of the least developed countries of late-nineteenth-century Europe, overlaid the veneer of “socialist utopia” on this image of paradise from England, the birthplace of industrial capitalism. In Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done? (1863), the heroine Vera Pavlovna sees “a building—a large, enormous structure” in a dream and asks: “But this building—what on earth is it? What style of architecture? There’s nothing at all like it now. No, there is one building that hints at it—the palace at Sydenham: cast iron and crystal, crystal and cast iron—nothing else.”17

The image of a greenhouse paradise is persistently maintained in this glass-encased utopia. Looking inside at “a field where grains are ripening,” Vera says: “There are tropical flowers and trees everywhere. The entire house is a huge winter garden.”18 In this enormous greenhouse, where all work is done by machines, the residents live happily, enjoying an appropriate amount of labor and leisure. The novel’s vision of a socialist paradise is essentially intermingled with this “archaic utopia of prehistory.” It is akin to a Russian version of the collective housing community of the future that Charles Fourier envisioned and dubbed “Palanstere.”

In Russia, the Crystal Palace was inextricably linked to the ideology of socialist utopia. This is evidenced by the fact that criticism of the latter had to take the form of criticism of the former. In 1864, the year after What Is to Be Done? was published, Dostoevsky dealt a blow to the Crystal Palace with the aim of criticizing Chernyshevsky’s socialist ideology. In what others hailed as a symbol of unity and progress for all humanity, Dostoevsky felt the shadow of an uncomfortable uniformity and the premonition of an anti-utopian nightmare:

Then—this is all what you say—new economic relations will be established, all ready-made and worked out with mathematical exactitude, so that every possible question will vanish in the twinkling of an eye, simply because every possible answer to it will be provided. Then the “Place of Crystal” will be built.19

According to the narrator of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864), the Crystal Palace symbolizes the triumph of an unwavering logic in which any form of doubt or denial is impossible. However, this triumph, and the impossibility of the negation of this logic, means the impossibility of man himself, as human existence will end when humanity’s dream is finally realized and all problems are resolved with no further conflicts or challenges.

On the one hand, these two nearly simultaneous prophecies were repeated again in the early 1900s. Aleksandr Bogdanov’s novel Red Star: The First Bolshevik Utopia (1908) is set on Mars, where a socialist revolution took place hundreds of years ago and society has thus already achieved a highly technological civilization. The residents live in houses with roofs and floors made of blue glass, which unfailingly brings to mind the Crystal Palace.20 On the other hand, in his 1924 novel We, Yevgeny Zamyatin transformed the Bogdanov-style utopia into an anti-utopia. The fictitious “One State,” constructed by humans who had survived two hundred years of horrific war, is reminiscent of a shining crystal. While looking up at the perfect sky, the protagonist D-503 states, “On days like this the whole world is cast of the same impregnable, eternal glass as the Green Wall, as all our buildings.”21 The sterilized future that he portrays is the same anti-utopia foreshadowed by Dostoevsky. In that world, the inhabitants (who have no names, just numbers) live in a uniform state in which everything works in sync, without a single error.

In the late 1920s and early ’30s, when Eisenstein was promoting The Glass House, he undoubtedly had this “Russian genealogy” of glass architecture in mind. The Glass House was not only a symbol of American capitalism; more than anything, it was a story about vision, about “seeing and being seen.” Eisenstein described the original script as “for the eyes, a comedy for the eyes.” It was the story of a people who see, or cannot see, one another while living in a house made of glass (ceilings, walls, and floors).22 In a world without distinction between inside and outside, and in a glass house where nothing can be hidden, the problem of “transparency” blurs the line between utopia and anti-utopia.

The mythology of the glass house spread to Germany in the early twentieth century in a new and powerful way. In this German interpretation, Eisenstein and Benjamin intersect in an exquisite fashion.

3.

Twentieth-century Germany was home to a true “prophet” of glass: Paul Scheerbart, who wrote strange stories that would now be called science fiction. In 1917, Benjamin took early notice of his work and wrote a short, favorable review of his fantasy novel Lesabéndio: An Asteroid Novel, featuring a spontaneous communal society on a utopian asteroid where private property had disappeared. Scheerbart’s name, however, appeared in earnest in Benjamin’s 1933 essay “Experience and Poverty.” In this text, Benjamin describes humanity’s destitute situation after the First World War not as a hopeless tragedy, but rather as an opportunity to “start from scratch; to make a new start”—“a new, positive concept of barbarism.” Scheerbart is introduced as one of the “constructors,” that is, one who adamantly rejects the “traditional noble image of man, festooned with all the sacrificial offerings of the past,” and who chooses radical newness as a cause, or, to borrow Benjamin’s memorable expression, the “inexorable ones who begin by clearing a tabula rasa.” People like Scheerbart are advocates of a dehumanized (entmenscht) humanity, or even of the inhuman (unmensch), because “humanlikeness—a principle of humanism—is something they reject.”23 But this was not even the most interesting aspect of Scheerbart’s thinking.

Scheerbart “placed the greatest value on housing his ‘people’—and, following this model, his fellow citizens—in buildings befitting their station.” Such buildings were “adjustable, movable glass-covered dwellings of the kind since built by Loos and Le Corbusier.”24 In addition to the fact that the inside of a glass house is transparent (i.e., is exposed to the outside), it also has another important characteristic: no traces are left on it—it has no “aura”:

It is no coincidence that glass is such a hard, smooth material to which nothing can be fixed. A cold and sober material into the bargain. Objects made of glass have no “aura.” Glass is, in general, the enemy of secrets. It is also the enemy of possession … Do people like Scheerbart dream of glass buildings because they are the spokesmen of a new poverty?25

The first thing that comes to mind from this perspective is naturally Benjamin’s 1929 essay “Surrealism.” While Benjamin is telling the story of Andre Breton’s Nadja, he (all of a sudden) connects a situation he witnessed in a Moscow hotel to “intoxication and “exhibitionism”:

[Breton] calls Nadja “a book with a banging door.” (In Moscow I lived in a hotel in which almost all the rooms were occupied by Tibetan lamas who had come to Moscow for a congress of Buddhist churches. I was struck by the number of doors in the corridors that were always left ajar … I found out that in these rooms lived members of a sect who had sworn never to occupy closed rooms …). To live in a glass house is a revolutionary virtue par excellence. It is also an intoxication, a moral exhibitionism, that we badly need.26

This passage, which connects the “open doors” of the Moscow hotel where the Tibetan lamas were staying with “moral exhibitionism,” as well as the meaning of the enigmatic phrase that speaks of “the revolutionary virtue of living in a glass house” (without mentioning Scheerbart’s name) is only clarified in an article written four years later. A house made of glass is the enemy of possession and secrets; everything inside can clearly be seen. It is ultimately the same place in which surrealism’s “best room” becomes impossible. Opening a closed door and exposing oneself to the outside is in line with “loosening of the self by intoxication.”27 Selfhood and individuality must break away from isolation, because there is no such thing as a “best room” for the contemplative self in this new space. The overall image of a space “where the ‘best room’ is missing” is tantamount to “the world of universal and integral actuality” and a publicly shared “body space.” The profound implications of the last passage of “Surrealism” become clearer when seen in this regard:

The long-sought image space is opened, the world of universal and integral actuality, where the “best room” is missing—the space, in a word, in which political materialism and physical creatureliness share the inner man, the psyche, the individual, or whatever else we wish to throw to them, with dialectical justice, so that no limb remains untorn. Nevertheless—indeed, precisely after such dialectical annihilation—this will still be an image space and, more concretely, a body space.28

Benjamin continues the discussion of the problem with intimate private space, as distinguished from public space, by providing a concrete historicity. For example, the “best room” in which the contemplative individual resides is given a specific face, as “a bourgeois room of the 1880s,” or more precisely, “the domestic interior” of the private individual under Louis Philippe. The “sclerotic liberal moral-humanistic ideal of freedom” liquidated by the surrealists is transformed into all sorts of “traces” left by the occupants of the room (The Arcades Project). According to this formulation, to reside means to leave a mark. But a wonderful phrase by Brecht helps us escape from this suffocating “phantasmagoria of the interior”: “Erase the traces!” Scheerbart appears here as the remover of traces. The creation of a space that cannot leave any traces is not only the path towards an art “without aura,” but also the creation of an environment for the birth of an entirely new human:

This has now been achieved by Scheerbart, with his glass, and by the Bauhaus, with its steel. They have created rooms in which it is hard to leave traces. “It follows from the foregoing,” Scheerbart declared a good twenty years ago, “that we can surely talk about a ‘culture of glass.’ The new glass-milieu will transform humanity utterly. And now it remains only to be wished that the new glass-culture will not encounter too many enemies.29

The terms “Bauhaus” and “culture of glass” that appear in the above quote immediately remind us of another German who cannot be left out of the genealogy of the glass house. He is the creator of the Glass Pavilion, the person who made Scheerbart’s idea into a physical entity: Bruno Taut.

4.

Bruno Taut first met Paul Scheerbart in 1912. The young architect, who had a keen interest in new materials and technologies, was instantly absorbed by Scheerbart’s idea of a glass utopia. An enthusiastic exchange of letters between the two began (it is said that they wrote several letters a day), and Taut made Scheerbart his de facto mentor. The young architect led Scheerbart to believe that his wild project could be realized, and eventually it was.

In 1914, two years after their first meeting, the first “Werkbund Exhibition” of the Deutsche Werkbund opened in Cologne. This exhibition is remembered for two buildings that paved the way for a new era in modern architecture. These were Walter Gropius’s Musterfabrik and Bruno Taut’s Glashaus. Taut, who had experimented with the utopian qualities of the new material in the so-called Monument of Iron at the “International Construction Exhibition” (1913), unveiled an unprecedented example of glass architecture that realized Scheerbart’s architectural fantasies. The giant glass tower that the protagonist in Lesabéndio was trying to build on an asteroid became part of the real world.

In 1914 Scheerbart wrote the book Glasarchitektur, a collection of aphorisms which sets forth the rules of the new architectural myths, and dedicated it to Taut. The crux of the book is the belief that “culture is created by architecture.” According to this concept, if we want to improve our culture, we have to first change its architecture; glass architecture is an option that will free us from confinement. As if responding to this proposition, the Glass Pavilion, which first appeared at the Cologne exhibition, was engraved with the following aphorisms, among others, on fourteen sides of the exterior wall of the building:

Glass brings us the new era; we only feel sorry for brick culture.

Without a glass palace, life is a burden.

Stained glass destroys hatred.

The double-skin glass dome was officially dedicated to Scheerbart, who attended the opening ceremony. This fantastical glass structure, which from afar resembles a flower bud or a bamboo shoot, not only embodies Scheerbart’s idea of glass architecture but also the long-evolved genealogy of the glass house, that is, the enclosed utopia of the Crystal Palace. The decorative glass space on the second floor—where the floor, the walls, and ceiling are all finished with glass—leads to a “staircase waterfall,” where water that wells up from a pond flows down the staircase. This gives rise to an impression no different from the image of the “garden” paradise intended by nineteenth-century landscape architect Joseph Paxton. Actually, Scheerbart cited the Berlin-Dahlem botanical garden in Germany as an example in the introduction to Glasarchitektur, which can be seen as a blueprint for this building. The elements of crystal, light, spirituality, plants, water, etc. that characterize the cultural myth of glass are all incorporated into the Glass Pavilion.

There is also a “cosmological” dimension of the glass house mythology. It does not require thinking of Bognadov’s Red Star or Scheerbart’s Lesabéndio, with the subtitle “An Asteroid Novel,” to see that glass architecture, starting from the Crystal Palace, is closely related to the idea of fantastically transforming the world through unity with cosmic space or the cosmic soul. Scheerbart was deeply influenced by the nineteenth-century cosmological philosophy of nature, especially by figures such as “Gustav Theodor Fechner, who was a professor at Leibniz University, French astronomer Camille Flammarion, and German philosopher and psychicist Carl Du Prel. All three were quite famous toward the end of the century and paid particular attention to the relation between the soul and the cosmos.”30

This relationship with cosmology is also reflected in the experience of the architectural structure and interior space of the building. Many visitors from that time mentioned that being inside the Pavilion was like floating in a state of no gravity. The floor, ceiling, and walls were finished with translucent glass, which confused any attempt to focus one’s vision on a singular place within the structure. Additionally, the glass dome that continues along an “oblique spiral” is a very rare structure that had no precedent, and it can be presumed that the “vortex” form was influenced by the widely known photographs of nebulas of the time. In other words, it is likely that Taut’s idea of bringing transcendental and permanent properties of the cosmos into architectural space was adopted.

Can we also find some trace of cosmology in Benjamin, who identified Scheerbart’s glass mythology as a symbol of a new mankind that would “clear a tabula rasa”? This topic would require a separate, close examination, but there is one obvious passage that comes to mind: “To the Planetarium,” the last of the short prose pieces from One-Way Street, published in 1928. In this piece, Benjamin notes that “absorption in a cosmic experience,” and “ecstatic contact with the cosmos” can happen “only communally.” He continues: “This immense wooing of the cosmos was enacted for the first time on a planetary scale—that is, in the spirit of technology.”31 After reminding us of World War I’s combination of cosmic power and large-scale technological war, he continues with a famous passage that reads more like a riddle: “Man as a species completed their development thousands of years ago; but mankind as a species is just beginning his. In technology a physis is being organized through which mankind’s contact with the cosmos takes a new and different form from that which it had in nations and families.”32 New relationships forged between mankind and the cosmos, which are different from the kind we find between ethnicities or other kin, are essentially related to the body (physis) being organized through technology to a new (second) nature. “First,” Benjamin explains, “people should discard the base and primitive belief that their task was to exploit the forces of nature; second, they should be true to the conviction that technology, by deliberating human being, would fraternally liberate the whole of creation.”33 These were two very important premises that Benjamin identified in Scheerbart’s philosophy. This also explains why Benjamin sometimes saw Scheerbart as “Fourier’s twin”:

In Fourier’s extravagant fantasies about the world of the Harmonians, there is as much mockery of present-day humanity as there is faith in a humanity of the future. In the German poet we find these elements in the same proportions. It is unlikely that the German utopian knew the work of his French counterpart. But we can be sure that the image of the planet Mercury teaching the Harmonians their mother tongue would have delighted Paul Scheerbart.34

Why doesn’t Benjamin mention Taut? He ties Fourier and Scheerbart together, but skips Taut and moves directly onto Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. It is possible that the cause of this “omission” may be found in Taut’s trajectory after the construction of the Glass Pavilion.

At the end of the First World War, Taut summoned a group of young people who shared his interests and attempted to realize Scheerbart’s idea in an even bolder fashion. The year 1918, when the November Revolution launched the Weimar Republic, also witnessed an architectural revolution that went hand in hand with the political one. That same November, the Workers’ Council for Art (Arbeitsrat für Kunst) was established in Berlin, following the model of the Soviet Workers’ Council. Bruno Taut was the leader of this group, which wanted to unite the arts “under the wings of a great architecture” to create new artistic values and a national structure. The two common denominators uniting the diverse group of people that gathered around Taut were the equation of architecture with creation, and a strong enthusiasm for glass. This shared passion continued in a loose correspondence community called the Glass Chain (Glässen Kette).

Meanwhile, the Workers’ Council for Art grew a bit too quickly, thanks to the excitement that accompanied the building of a new socialist state. As the organization got larger, Taut became concerned with excessive bureaucracy, and stepped down in February 1919 after less than three months as its leader. Walter Gropius succeeded Taut as its head. In April of that same year, Gropius gave the opening remarks at the “Exhibition of Unknown Architects,” organized by the Workers’ Council for Art. The text for these opening remarks was in fact the text of the famous Bauhaus Manifesto (1919): “Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”

When writing the essay “Experience and Poverty” on the island of Ibiza in 1933, Benjamin may have overlooked Scheerbart’s mentee, Bruno Taut, in favor of the first principal of the Bauhaus, Gropius. By this time, Scheerbart had established himself as the “prophet of glass,” and Bauhaus was becoming a powerful contemporary art movement, opening a new chapter in modernity. Taut, however, was stepping back from the front lines and preparing for the second act of his new life. He went to Japan in 1933 to escape the Nazis. Three years later he was invited to teach at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul, Turkey. We are thus left with one last question. While preparing for The Glass House project in the late 1920s, did Eisenstein have Taut in mind? Had the two ever met in person?

5.

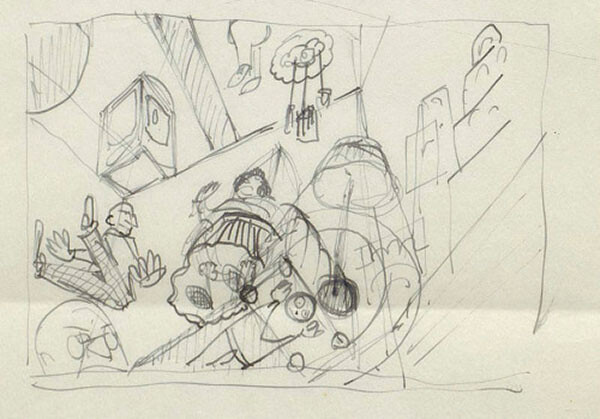

Eisenstein’s project for The Glass House is extremely difficult to reconstruct due to the notorious ambiguity and fragmented nature of his notes. Nevertheless, it is clearly perceptible that the ideological premise of the project reflects the cultural myth of glass architecture, particularly its utopian dimension, which we have already examined to some extent. It is quite possible that Eisenstein met Bruno Taut or his close colleague Adolf Behne in person. At that time, Behne was part of the leadership of the Society of Friends of the New Russia and visited the Soviet Union in 1923. Taut was also an active member of this association, and is known to have visited the Soviet Union several times, beginning in 1926.

The archives found in the Eisenstein Museum provide us with the most interesting information. Among the materials that Eisenstein would have read were Ludwig Hilbersiemer’s essay “Glasarchitektur,” which introduces Scheerbart’s ideas and Taut’s works, and the German magazine Das Neue Berlin, which carried news of the founding of the Paul Scheerbart Association.35

Eisenstein’s sketch for the unrealized movie The Glass House (1928).

The fact that Eisenstein read these materials, that he was familiar not only with the “Russian genealogy” of glass architecture triggered by the Crystal Palace, but also with the “German genealogy” that started with Scheerbart, helps us understand the fate of his project The Glass House, namely, its ultimate failure. The original concept of a glass tower, which might have begun simply as an architectural image of American capitalism, was bound to diverge and expand uncontrollably the moment the motifs and associations of the European myths surrounding glass architecture caught up with it, eventually leading to endless adaptations and transformations. The cultural myth of the glass house, which started with the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, has been used as a powerful narrative in the search for a blueprint for a new world (and a new human), as well as a means of overcoming capitalist modernity, reviving archaic utopian dreams against the background of the catastrophic situation (of war and revolution) at the turn of the century.

At the same time, as the ideal of universal human harmony and its accompanying “transparency” that the glass house represents became intertwined with its exact opposite—totalitarian surveillance and the nightmare of spectacle—it evolved into the two faces of utopia and anti-utopia, of messianism and the apocalypse.36

In this respect, like Eisenstein’s other unrealized projects, The Glass House is yet another instance of the history of a failure revealing much more than the failure itself. To borrow Alexander Kluge’s astute expression in reference to Eisenstein’s Capital project, it is like an “imaginary quarry” placed before us.37 As we dig through the rubble for the best texts buried in the pile of historical debris, we see a deeper and more extensive “stratum” lying beneath it. The thoughts of Eisenstein and Benjamin, who lived as contemporaries in this turbulent era, as well as the texts they left behind, are optimal signposts for exploring these “veins,” making the exploration of their ideas, especially in the light of the other’s, a worthwhile effort.

This text is a revised and supplemented version of “Yurijibui munhwajeok gyebohak” (The Cultural genealogy of The Glass House), Bigyomunhak (Comparative literature), vol. 81 (2020). An abbreviated version of the latter was published in the catalog LEE BUL: Утопия Спасённая (Utopia saved) (Манежсс, 2020), 124–44.

For further details, see Soo Hwan Kim, “Sergei Tretyakov Revisited: The Cases of Walter Benjamin and Hito Steyerl,” e-flux journal, no. 104 (November 2019) →.

For the above, see Eisenstein Rediscovered, ed. Ian Christie and Richard Taylor (Routledge, 1993), 117.

Eisenstein traveled abroad for almost three years (September 1929 to May 1932) with cinematographer Eduard Tisse and assistant director Grigori Aleksandrov under the pretext of examining Western cinema’s sound technology. He gave lectures in various parts of Europe (Berlin, Zurich, Ghent, London, Paris, Amsterdam), met people like James Joyce, Bernard Shaw, Abel Gance, Louis Bunuel, Hans Richter, and Moholy-Nagy, and after signing with Paramount Pictures, went to the United States and communicated with well-known figures like Charlie Chaplin and Walt Disney. Later, while filming Que viva Mexico! in Mexico, he returned to the Soviet Union upon Stalin’s orders, leaving the film unfinished.

On January 24, 1927, about a month and a half after coming to Moscow, he saw the film with an interpreter, and two days later, on January 26, he wrote the review. The piece was published in Die Literarische Welt immediately after his return to Berlin in March 1927.

Walter Benjamin, “Reply to Oscar A. H. Schmitz,” in Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 1, 1927–1930, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Belknap Press, 1999), 17.

Benjamin, “Reply to Oscar A. H. Schmitz,” 16.

These intersections can also be identified through the common denominator of Baudelaire. As a precursor to his shock effect, Eisenstein quoted from Baudelaire’s journal in his 1929 essay “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form,” noting that “irregularity—that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment, are an essential part and characteristics of beauty.” Benjamin also connected the unexpected and the irregular in Baudelaire’s poetry to modern urban life in general and, formally, to methods of film. “In film, perception in the form of shocks was established as a formal principle.” See James Goodwin, Eisenstein, Cinema, and History (University of Illinois Press, 1993), 76.

Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (MIT Press, 1989), 95.

Naum Kleiman, “Стеклянный Дом: С. М. Эйзенштейна. К истории замысла” (The Glass House: S. M. Eisenstein. On the history of the idea), Искусство кино, no. 3 (1979): 94–114.

Oksana Bulgakowa, “Eisenstein, the Glass House and the Spherical Book: From the Comedy of the Eye to a Drama of Enlightenment,” Rouge, no. 7 (2005) →.

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 1935–1938, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Belknap Press, 2002), 36.

This outsized building (564 × 33 × 124 meters), with 3,300 columns made of 4,500 tons of cast iron and 293,655 glass panels, was completed in just seven months.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 37.

Giorgio Agamben, Means Without End: Notes on Politics, trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 75.

Quoted in Buck-Morss, Dialectics of Seeing, 85.

Nikolai Chernyshevsky, What Is to Be Done?, trans. Michael R. Katz (Cornell University Press, 1989), 384.

Chernyshevsky, What Is to Be Done?, 385.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground, trans. Constance Garnett (Heritage Press, 1967), 15.

Aleksander Bogdanov, Red Star, trans. Charles Rougle (Indiana University Press, 1984).

Yevgeny Zamyatin, We, trans. Clarence Brown (Penguin, 1993), 3.

Bulgakowa, “Eisenstein, the Glass House and the Spherical Book.”

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 1931–1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Belknap Press, 1999), 732–33.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 733.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 734.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 1, 209.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 1, 208.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 1, 217.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 734.

Михамл Ямпольский, Наблюдатель Очери истории видения (The observer: Essays on the history of vision) (Москва, 2000), 144.

Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (NLB, 1979), 104.

Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, 104.

Walter Benjamin, “On Scheerbart,” in Selected Writings, vol. 4, 1938–1940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Belknap Press, 2006), 386. This piece, written in French and not published during Benjamin’s lifetime, is believed to have been written in the late 1930s or ’40s. The concept of “fraternity” that appears in the phrase “liberating all of creation on the basis of fraternity” is reminiscent of his concept of “redemption” that emerged in his later years and of the concept of immortality and resurrection particular to Russian cosmism of the twentieth century. However, there is not yet any evidence that suggests Benjamin was directly influenced by Russian cosmism.

Benjamin, “On Scheerbart,” 387–88.

Ямпольский, Наблюдатель (The observer), 166–67.

For example, contemporary artist Zoe Beloff linked the potential energy of Eisenstein’s unfinished project, among others, to the issue of digitalized “global surveillance systems” in her essay film Glass House (2015). See →.

Sergei Eisenstein and Alexander Kluge, Notes on Capital, trans. Soo Hwan Kim and Yoon Sung You (Seoul: Munhakyazisungsa, 2020), 161.