Hear us, you who are no more than leaves always falling, you mortals benighted by nature,

You enfeebled and powerless creatures of earth always haunting a world of mere shadows,

Entities without wings, insubstantial as dreams, you ephemeral things, you human beings:

Turn your minds to our words, our ethereal words, for the words of the birds last forever!—Aristophanes, The Birds1

1. The Preserving Machine2

Set in mid-1950s Europe, Philip K. Dick’s fable “The Preserving Machine” describes the pursuits of a scientist named Doc Labyrinth. In the aftermath of the two world wars, Labyrinth is contemplating the possibility of a human-made disaster that could wipe out civilization. While working in his lab, he ponders the possible loss of classical European music should the apocalypse occur. Inspired by a vision of a resilient beetle crawling out of the rubble, he decides to create a “preserving machine” that could encapsulate classical compositions in the bodies of animals. If the beetle is the only thing to rise from the ashes, he thinks, let it carry the world’s greatest symphonies.

Labyrinth successfully creates the preserving machine. He feeds musical score sheets into the machine, and each produces a different animal: “Mozart emerges in the body of a small bird, Beethoven comes out as a beetle, Schubert is a sheep and so on.” The doctor creates several animals, each one unique, each embodying a composer’s work, and releases them into a forested grove behind his lab. The hope is that when the animals are someday fed back into the machine they will release the music they have preserved in their bodies. However, sometime later, he finds that the animals in the forest have died, mutated, or become feral. “He had forgotten the lesson of the Garden of Eden: that once a thing has been fashioned it begins to exist on its own, and thus ceases to be the property of its creator to mold and direct as he wishes … he had ensured their survival, but erased their meaning.” Finally, he captures a beetle and feeds it back into the preserving machine, expecting to hear Bach. Instead, the sound that emerges is wild and hideous.3

Dick’s fable is one of morality: nature will not submit to human will. Faced with the violence of war, Labyrinth comforts himself with European symbols of civility and resilience, despite the fact that the Second World War was clearly driven by racial cleansing. Besides the loss of music, he fantasizes about the destruction of museums: the institutions that affirm Europe as the pinnacle of advanced civilization. Following his failed experiment he remarks, “Perhaps nothing can be done, then, to save those manners and morals,” as if unaware, or unwilling to consider, that most of the artifacts in museums are violent acquisitions from other lands.4 The satirical story has many such aspects that reek of white supremacy: the binary reflection between “mannered” and “wild,” the nod to biological purism, and the idea that for culture to survive we must prevent mixing or intermingling. In his desire to keep things as they are, Labyrinth overlooks the obvious: that things need to change, evolve, and adapt in order to survive. His vision of exceptionalism, consistent with European values at the time, shows that purity and selective breeding leads to death, disease, and stagnation. In the story, the machine itself does no preserving whatsoever: the animal stores the music—and then transforms it. But animals cannot be expected to preserve information perfectly; they are not machines. Or are they?

Artist Dora Budor’s The Preserving Machine (2018–present) is an art installation based on Dick’s short story. In Budor’s version, the machine is a robotic flying apparatus made to look like a bird. Its flight pattern is designed in accordance with a musical score that the viewer can’t hear; its movements are programmed in biomimetic patterns that correspond to a site-specific sound composition. Her bird seemingly adapts to different scenarios: At the 2018 Baltic Triennial in Vilnius, Lithuania, organized around the theme “Give up the Ghost,” the bird flew around the central courtyard of the Contemporary Art Centre. The courtyard’s glass walls were tinted acid yellow, giving the impression from within the building that the air outside was yellow. Looking out, one could imagine an abandoned environment where a single bird aimlessly flaps around a deserted landscape. At Budor’s 2019 solo show at Kunsthalle Basel, entitled “I am Gong,” the bird was kept inside, in a yellow plastic enclosure that brought to mind containment structures on toxic or radioactive land sites in science fiction films.

In Vilnius, the viewer was in a position of confinement, with the artwork in the wild; in Basel the work was confined, with the viewer looking in. In both cases, the floor of the exhibition space was covered with diatomaceous earth—essentially fossil dust—and construction materials from nearby sites. The flapping mechanical animal was contextualized by both ancient dust and contemporary relics. In 1921 Walter Benjamin wrote of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, the famous monoprint that depicts an angel backing away from the viewer: “This is how one pictures the angel of history. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”5 Likewise, Budor’s bird is flung back and forth through space and time, seemingly oblivious to the destruction around it or the fact that it is contained or not. However, unlike the “angel of history,” the bird’s path is not linear but repetitive.

The composers chosen by Doc Labyrinth represent a political web of entanglements that helped form contemporary European identity. The continent’s ideological underpinnings are clearly audible in the celebrated compositions of eighteenth-century Western Europe. Bach, for example, occupies such a historical position. A German, he was influenced by both Italian opera and French absolutism. His task was to reconcile the somber tones of German repertory with French dance and Italian drama for a growing Europe that embraced convergence, along with continental philosophy and the rise of Prussia. German art and music has always had a certain reverence for nature, but ongoing tensions with the Holy Roman Empire complicated that relationship by counterposing the Christian against the natural. Music reflects changes in the world: its mechanism relies on making noise palatable by means of subjectively defined order. The dialectic between order and violence mirrors another dialectic between music and pure noise: each reveals hidden physical and social architectures. By examining degrees of deviation from order, one can decipher the social code of a society at a particular time.

Budor’s machine-bird preserves the symphony-code through its flight pattern, marking a territorial soundscape—translating sound into movement for the viewer to see but not hear. Its programmed behavior raises questions around “coding” as a cultural and biological instrument. Unlike literature or art, music appears to be nonrepresentational, at least at first. “But music also is a place of sorts,” says musicologist Holly Watkins, who has written extensively on the subject of acoustic bio-entanglement.6 Human and animal utterances articulate distance, texture, and intent. They respond to the acoustics of landscapes; they are amplified in some spaces and dampened in others. The quality, cadence, and rhythm of uttered sounds serve different purposes of survival and movement. They can document changes in landscape through their evolution. Through instances of human relation to birdsong and other natural sounds, and the way they have been transcribed, adapted, and memorialized by humans throughout millennia, we can trace otherwise invisible political interventions into landscapes and soundscapes.

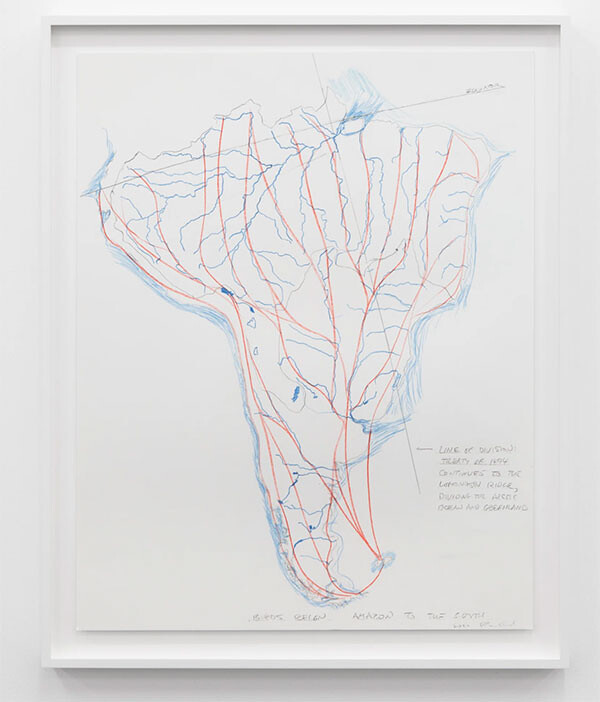

Peter Fend, Birds Reign—Amazon to the South, 2020. Pencil and colored pencil on paper. 60.96 × 45.72 cm / 24 × 18. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin.

2. Guided by Voices

The term “birdsong” is contested by musicologists. There is much potential slippage between the melodic sounds produced by a bird and songs composed by humans, but song has long been thought to be the purview of the human creator: “That which makes music an art is that which separates it from nature and the natural voices of birds,” writes Elizabeth Leach.7 There is a pervasive philosophical and musicological reluctance to accept birdsong as music: to imbue it with artistic intent would seem to interrupt its natural authenticity. Throughout history, meaning has nonetheless been ascribed to birdsong by humans. Birds are known for their talent of mimicry, but the reverse is also true. While Kant, for instance, insists that birdsong cannot be imitated, bird sounds have often been the subject of musical investigation and improvisation.8 Schumann, Messiaen, Handel, Dvorak, and other composers worked with birds. The integration of birdsong into musical compositions has been part of Western classical music at least since the fourteenth century, and early recordings of birdsong also inspired biomimetic interventions into species.

For instance, the canary bird was selectively bred across Russia and Germany for its ability to imitate the sounds of birds who were more difficult to domesticate, such as the nightingale. The canary genus “has a remarkable ability to transform and imitate virtually any sequence of pitches, whether produced by humans or other birds.”9 Russian and German trainers had distinctly different approaches to training the bird, each tailored to their respective understandings of what’s natural. While the German canary produced “the peaceful, evening tones of the nightingale,” the Russian birds evoked the “wild birds of the forest.”10 Human trainers have influenced the “natural” occurrence of birdsong not despite, but precisely because of, the technical capacities of the particular bird that allow it to be trained.

Budor’s machine-bird preserves a sonic composition through its flight pattern, marking a territory. According to Deleuze, “The bird sings its territory, or rather, the territory as a relational rhythmic act sings itself through the bird, as the refrain actualizes musical points of order, circles of control and lines of flight.”11 For Deleuze and Guattari, birds are artists, and birdsongs are expressions of the territorial milieu of the bird’s landscape: deterritorialized and removed from context, “they become part of autonomous “rhythmic characters” and “melodic landscapes” that tend beyond the territory toward the cosmos as a whole.”12 The bird tells the story of its landscape through song, and a species of bird that migrates might be able to pass on these songs through generations, providing a territorial context for future generations of birds. This can continue for millions of years. Reports from Australia’s Great Dividing Range in southern Queensland describe how the recent bushfires of 2019 potentially wiped out entire species of birds: birds that have been singing the same songs for millions of years. According to one news report, “It is said that all the birdsongs in the world go back to these birds.”13 If birdsong describes a territory, then these songs are the only living record of landscapes that no longer exist. This constitutes a major loss not just for biodiversity but for the potential in accessing these sonic records. The complexity of belonging to a geographical area feeds and inspires ways of remembering, for humans as well as birds. As Deleuze writes: “As birds sing their territory, so do humans speak or sing theirs.”14

Moscow, the city of my childhood, is marked by brutal concrete buildings. The spaces create acoustic conditions that require a low, conspiratorial speaking voice that reduces the possibility of an echo. However, conspiratorial voices lead to conspiratorial identities that “affect our minds and our body.”15 When an outsider from a radically different geography, for example a desert, visits Moscow, their voice, trained to roll across dry, expansive distances, bounces around the wet concrete structures, breeding discomfort and xenophobia in the locals. The outsider brings a public disturbance, but furthermore, the outsider brings the knowledge of a different, non-conspiring world. In this vein, Watkins says that “music constitutes a virtual environment related in subtle or overt ways to actual environments.”16 Examples include music that patently engages in the imagination of place. “From the nationalistic compositions of the late-nineteenth century to contemporary popular music, from Bedřich Smetana’s Ma Vlast (My Country) to John Denver’s ‘Take Me Home, Country Roads,’” composers and performing artists have forged “‘narratives of locality’ using manifold poetic and musical means.”17 Architectural, textural, and geographical features affect the way that sound travels in space, and humans inhabiting different landscapes have developed musical methodologies to commune with their environments, and sometimes to preserve place-based heritage—even when this heritage perpetuates xenophobia, colonialism, and violence.18

If both human music and birdsong respond to space—by articulating a relation between memories, sound, and place—then by altering, imitating, and reproducing melodies, humans alter landscapes too. Song is a species-specific document of and a map to a history of geological, political, biological, and industrial change. Watkins asserts that “musical fictionalizations of place encode historically shifting attitudes about humanity, nature, and their interaction—attitudes that demand and deserve careful study.”19 Relying on assumptions and metaphors about sound reaffirms the mythical status of nature through rhetorical means. Revising this metaphorical structure allows us to reevaluate the technological relation between humans and nature, and reexamine the human relationship to history.

Steven Feld, Voices of the Rainforest: A Day in the Life of Bosavi, 2019. 70 minutes, 7.1 surround sound film, Distributed by Documentary Educational Resources, www.der.org. In Feld’s film, “This image appears at the beginning of the section with the performance of the mouth harp. The bird superimposed on the landscape looking south to Mt. Bosavi is the Papuan hornbill, Rhyticeros plicatus, (obei, in the Bosavi language) which is locally a prominent male spirit symbol and thus the bird local consultants suggested frame this very male afternoon forest activity.”

3. Imagine All the People

Steven Feld is an ethnomusicologist working with the Kaluli people in the Bosavi region of Papua New Guinea. In his book Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression, he describes a group of people living in a rainforest, surrounded by birds. Their daily lives, writes Feld, are greatly influenced by their interactions with these animals. He believes these interactions inspire

a set of beliefs that organizes the interpretation of everyday living in a world that is full of birds and alive with their sounds. Myths, seasons, colors, gender, taboos, curses, spells, time, space, and naming are systematically patterned; all of these are grounded in the perception of birds, as indicated foremost by the presence of sound.20

Many of the birds represent dead ancestors, and their songs are understood as weeping, grieving sounds, mediating between the spiritual and the practical world. Feld claims that the Kaluli people try to imitate the sounds of birds when they want to evoke a sense of reminiscence and nostalgia: the tones prepares an audience for a certain kind of remembering.21 And so when composing these songs, the Kaluli try to vocalize in a “bird language” which, unlike practical everyday language, evokes memories, events, and most of all, places. “Re-membering is a bodily activity of re-turning.”22 In his description of the songs, Feld says that “all songs are sung from the point of view of movement through lands. The composer’s craft is not to tell people about places but to suspend them into those places.”23

As musicologist Susan McClary has written, “Music enters through the ear, that most vulnerable organ of perception that cannot be opened or closed selectively. And especially in Western culture, where the visual is a privileged source of knowledge, it tends to slip around and surprise us.”24 Music is a powerful mnemonic device when it comes to language as well as place: the human brain uses phonology to memorize certain parts of language.25 Studies show that it is a song’s structure that helps us remember other information about it. In other words: the melody helps us recall the lyrics. This is why a sentence heard repeatedly starts to acquire a rhythm. Tones can resonate inside the body, specifically in the ears, creating independent sounds based on internal acoustics and associations.26 “Behavioural experiments with songbirds help to throw light not only on how and why humans recognize and learn to manipulate melodies and language, but also on how the human brain functions more generally,” according to philosophers Olga Petri and Peter Howell.27 For instance, studies of canaries were some of the first to suggest brain plasticity in humans.

In 2019 artist Byungseo Yoo explained to me that his exploration of minimalist techno music was an experiment in memory. While listening to a repetitive beat, he said, one constructs a unique melody hinging on one’s perspective and personal associations. So while a group of people appear to be dancing together to a repetitive beat in a club, each person is dancing to their own internal song. The song is created by memories, associations, and familiarities, but it is also formed by the body. The bodies of other dancers dampen and absorb sounds too, creating other acoustics that resonate in the space. The repetitive beat mediates between the collective experience and the song inside.

At the Banff Centre in 2017, I attended a concert performance of A Song for Margrit, a composition by the late composer Pauline Oliveros in which the players make sounds in response to any sound they hear in the room, which can also come from the audience. The session was guided by the Toronto experimental musician Anne Bourne. Oliveros’s works, often performed communally, allude to de-skilling and a form of performance that functions “without the mediating code of musical performance history.”28 When the group of improvisors started playing, it felt like the sounds were articulating some already existing social dynamic among the musicians: hierarchies audibly and visibly emerged as the performers exchanged glances and took turns, some yielding and some interrupting. After the first set, they performed a second iteration of the improvisation, in which half of the performers were blindfolded. Without the visual communication they had relied on before, the melody changed into a softer, more collaborative rhythm. Bill Dietz and Gavin Steingo write in their article “Experiments in Civility” that “within the performing collective, the literal relations between musicians, their perception of each other’s cues and coordinations, describe an indeterminate geography in which sound becomes secondary to the intersubjective, collective execution of it.”29

At the 2016 Montreal Biennale, I watched Marina Rosenfeld stage a second iteration of her experimental Free Exercise performance (first performed in 2014). A hybrid orchestra made up of both civilian and military participants carried out a series of musical “exercises.” This sixty-minute version was a collaboration between a military orchestra (wearing full camouflage) and local musicians, held at the armory of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal. As the orchestra began performing, a crowd of exhausted but giddy art viewers, journalists, and locals trickled into the decorated hall. Each audience member had their own preconceptions about the setting and the performers: the majority of the crowd had likely never set foot in an armory. The different sensibilities of the two groups of performers contributed to a sense of gentle conflict between a group that wanted to retain control over the score, and a group of disrupting bodies.30 The dynamic between the groups illuminated a social tension that already existed in the room, a kind of orchestrated resistance that has been so central to the landscape of political performance art.31

The Birds of Aristophanes as Performed by Members of the University at the Theatre Royal: Cambridge, November, 1883.

4. Signal

In his 1974 essay “What is it Like to Be a Bat?” philosopher Thomas Nagel makes a clear distinction between being something and being “like” something. He describes this as the difference between being and pretending. Of course humans are able to imagine being bats—it’s fun to speculate what it would be like to fly around in total darkness, guided by echolocation, to hang upside down and eat bugs—but this projection is distinctly separate from actually being a bat.32 Even if we suddenly somehow did become bats, Nagel believes that our human consciousness would prevent us from fully experiencing it. He proclaims that “our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience” and that every projection is connected to a single point of view.33 If you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail. But if you’re a nail, does everything look like a hammer?

“We all know that people have politics, not things,” writes Langdon Winner in his text “Do Artefacts Have Politics?” “Technological change expresses a panoply of human motives, not the least of which is the desire of some to have dominion over others.”34 Ultimately, Philip K. Dick’s story is that of a man who wants to have absolute power over history by creating a mini-cosmos in his own backyard. Like a melody you keep coming back to, an infectious song stuck in your head that absorbs or excludes all extraneous voices, the human domain perpetuates itself through the imagining and reimagining of civilities.35 In reality, the nature-culture structure is an illusion of convenience: waking life is not a grove full of domesticated monsters behind the master’s house but a vast and unpredictable landscape.

Listening to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, one can grasp much about the cultural and political alliances of eighteenth-century Western Europe. But taken out of context, the symphonies that Doc Labyrinth longs to preserve lose much of their meaning. What a listener can glean from music relies on individual and collective beliefs about history and politics. By bringing to life the Mozart bird, Budor’s installation awakens in the viewer a new perspective on Dick’s story, exposing the pillars of the author’s imaginary space. Outside the realm of the fable, Labyrinth’s grove of engineered creatures is not so much a Garden of Eden as a certain type of Noah’s Ark. It is the scientist’s rationalized, self-contained vessel, where pre-selected binaries await to populate a new world.

Winner challenges us to uncover new kinds of biases that are inherent to imaginary political spaces. “In doing so,” writes Martha Kenney, “[Winner] addresses his reader, implicates us, and insists that we pay attention”; he “renders us responsible” for the production of those spaces.36 It’s not music itself that guides us: as Dietz and Steingo write, “You can’t trust music.”37 Music itself is uncertain, avoidant, nonpartisan: it renders a flexible terrain. In fact, “it is not, as the reactionaries accuse, that it is decadent, individualistic, or a-social. It is that it is those things too little.”38 Animal music, and music created in collaboration with animals, offers a glimpse into alternative histories that prioritize other perspectives. Could the space of projection that opens when humans assign meaning to birdsong offer a mixed perspective, a shared opportunity to navigate the future? From Noah’s dove to canaries in the coalmine, birds are sentinel species. Their songs preserve a history of geopolitics, and simultaneously, a warning about a future history of human intervention.

Aristophanes, Aristophanes: The Birds and Other Plays, trans. David Barrett and Alan Sommerstein (Penguin Classics, 1978).

The title of this essay, “You can’t trust music,” is a quotation from Bill Dietz and Gavin Steingo, “Experiments in Civility,” boundary 2 43, no. 1 (2016): 43.

Philip K. Dick, “The Preserving Machine,” Science Fiction Studies 2, no. 1 (1975): 22–23.

Dick, “The Preserving Machine,” 23.

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (Schocken Books, 1969), 249. Allen Dunn explains that Benjamin purchased Angelus Novus from Klee immediately after its completion in 1920 and tried on several occasions to peddle the image as a starting point for a number of ventures, including a namesake publication. “Through repeated references to the painting, Benjamin often balances his own moral economy by creating a rhetorical narrative that relies on the linearity of history told from a single perspective.” Allen Dunn, “The Pleasures of the Text: Angelus Novus,” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 84, no. 1–2 (2001): 3.

Holly Watkins, “Musical Ecologies of Place and Placelessness,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64, no. 2 (2011): 405.

Elizabeth Eva Leach, Sung Birds: Music, Nature, and Poetry in the Later Middle Ages (Cornell University Press, 2007), 3. Leach elaborates: The “performer of music is under an obligation not just to make musical sounds but to understand them as music, that is, as proportions that are rational. The listener is also under an obligation to understand sounds in this way, whether or not their performing agent does so” (3).

Kant says that “a bird’s song, which we can reduce to no musical rule, seems to have more freedom in it, and thus to offer more for taste, than the human voice singing in accordance with all the rules that the art of music prescribes.” Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, ed. Nicholas Walker, trans. James Creed Meredith (Oxford University Press, 2008), 73.

Luis F. Baptista and Sandra L. L. Gaunt. “Advances in Studies of Avian Sound Communication,” The Condor 96, no. 3 (1994): 820.

Jacob Smith, Eco-Sonic Media (University of California Press, 2015), 50.

Quoted in Ronald Bogue, “Minority, Territory, Music,” in Deleuze’s Way: Essays in Transverse Ethics and Aesthetics (Routledge, 2007), 20.

Bogue, “Minority, Territory, Music,” 29.

Ann Arnold, “Bushfires Devastate Rare and Enchanting Wildlife as ‘Permanently Wet’ Forests Burn for First Time,” ABC News, November 26, 2019 →.

Bogue, “Minority, Territory, Music,” 32.

Maryanne Amacher, “Psychoacoustic Phenomena in Musical Composition: Some Features of a ‘Perceptual Geography,’” FO(A)RM, no. 3 (2004): 16.

“The vocabulary of virtuality overlaps with semiotic studies that frame musical experience as an encounter with virtual agents.” Watkins, “Musical Ecologies,” 405.

Watkins, “Musical Ecologies,” 405.

Coralie Hancock-Barnett, “Colonial Resettlement and Cultural Resistance: The Mbira Music of Zimbabwe,” Social and Cultural Geography 13, no. 1 (2012): 11–27.

Watkins, “Musical Ecologies,” 405.

Steven Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression (Duke University Press, 2012), 84.

Karen Barad speaks of “an embodied re-membering of the past which, against the colonialist practices of erasure and avoidance and the related desire to set time aright, calls for thinking a certain undoing of time; a work of mourning more accountable to, and doing justice to, the victims of ecological destruction and of racist, colonialist, and nationalist violence, human and otherwise—those victims who are no longer there, and those yet to come.” Karen Barad, “Troubling Time/s and Ecologies of Nothingness: Re-turning, Re-membering, and Facing the Incalculable,” new formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, vol. 92 (2018): 59.

Barad, “Troubling Time/s,” 60

Feld, Sound and Sentiment, 135.

Susan McClary, “The Blasphemy of Talking Politics during Bach Year,” in Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance and Reception, ed. Richard Leppert and Susan McClary (Cambridge, 1987), 13–62.

W. T. Wallace, N. Siddiqua, and A. K. M. Harun-ar-Rashid, “Memory for Music: Effects of Melody on Recall of Text,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 20, no. 6 (1994): 1477.

Amacher, “Psychoacoustic Phenomena,” 10.

Olga Petri and Peter Howell, ”From the Dawn Chorus to the Canary Choir: Notes on the Unnatural History of Birdsong,” Humanimalia 11, no. 2 (Spring 2020): 168.

Bill Dietz and Gavin Steingo, “Experiments in Civility,” boundary 2 43, no. 1 (2016): 70.

Dietz and Steingo, “Experiments in Civility,” 70.

“Adorno extolls the anti-choreography of postwar music—music to which (in theory) no one could bob one’s head, sing along, or march in step—to be a reaction to war-time orchestras.” Dietz and Steingo, “Experiments in Civility,” 45.

Even “Marx knew only too well (that) simply uncovering the social relations and necessary labor time behind commodities through analysis does not lead to the end of capitalism.” Dietz and Gavin Steingo, “Experiments in Civility,” 58.

In Feld’s studies, the Kaluli make a distinction between birds and bats, despite their obvious similarities as flying creatures. Kaluli will openly discuss the avian nature of bats, but if asked directly, “Are bats birds?” the answer is a fairly immediate “no,” followed by, “It has no voice.” Feld, Sound and Sentiment, 84.

Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The Philosophical Review 83, no. 4 (October 1974): 438.

Langdon Winner, “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” in The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology (University of Chicago Press, 1986), 20, 24.

John Lennon’s famous anti-war plea starts and stops at asking listeners to “Imagine” a better world. It amounts to a rather apathetic call for action: to dream about a better world, without really doing anything about it. “You may say I’m a dreamer / But I’m not the only one / I hope someday you’ll join us / And the world will live as one.” Lennon sings about a privileged refusal to act—dreaming, sleeping, and being photographed in bed while the world burns. By contrast, Kendrick Lamar sings about why he can’t get any rest in his 2012 song “Sing About Me, I’m Dyin’ of Thirst”: “Maybe ‘cause I’m a dreamer and sleep is the cousin of death / Really stuck in the scheme of wondering when I’ma rest.” To dream can be fatal, if you aren’t rich.

Martha Kenney, “Fables of Response-ability: Feminist Science Studies as Didactic Literature,” Catalyst 5, no. 1 (2019): 6, 43.

Dietz and Steingo, “Experiments in Civility,” 43.

Adorno, as quoted in Heinz-Klaus Metzger, “John Cage oder Die freigelassene Musik,” in Die freigelassene Musik: Schriften zu John Cage, ed. Rainer Riehn and Florian Neuener (Klever Verlag, 2012), 10. Trans. Bill Dietz.

I am grateful to Dora Budor, Anne Bourne, Christopher Willes, Kenneth McLeod, and Steven Feld for their part in this research. With sincere thanks to Elvia Wilk and Julieta Aranda.