I.

The vista painted for us by Bruno Latour, Eva Lin, and Martin Guinard in their concept for the Taipei Biennial 2020 is alarming: “We are witnessing a massive extension of conflicts and an extreme brutalization of politics. The ‘international order’ is being systematically dismantled … We lack a common world.” The divisions are so deep that we can no longer even define peace and war. “It is crucially important to explore alternative modes of encounter … to avoid destruction,” yet we cannot do so on the assumption of an overarching authority, which is precisely what no longer exists. “The present imperative is not simply to foster a discussion among a multiplicity of perspectives, since this would inevitably fall back to older models of universalism” in a vain attempt to reconcile “multiple visions of the same natural world. The aim … is to explore alternative procedures that still aim at some sort of settlement, but only after having fully accepted that divisions go much deeper than those anticipated by old universalist visions.” This is what Latour, Lin, and Guinard mean by “new diplomatic encounters.”1

Latour first began developing his diagnosis of the contemporary crisis thirty years ago with We Have Never Been Modern.2 It is a complex and continuously evolving project reflecting, on the one hand, on the displacement of a stable nature as common ground, by what he calls Gaia. On the other hand, he is responding to the political impasse of modernity, which is at its most extreme in the Anglosphere. His 2017 Down to Earth was a direct response to the double crisis of 2016: Brexit and Trump.3

But there is another strand in Latour’s contemporary diagnosis that informs the insistence on “diplomatic encounters”—the work of Carl Schmitt. And this is also the point at which the diagnosis misleads us. Reanimating Schmitt’s critique of liberal modernity born out of the violence of Europe’s early twentieth century serves as much to compound as to illuminate our current impasse. It is time to provincialize Schmitt’s critique. It is time also to put the know-nothing, climate-denial tactics of a small fraction of the US elite in their historic place. Elon Musk’s rockets may capture headlines, but the strategy that Latour has dubbed “escape,” or “exit,” is a dead end. And that fact is evident not only to the EU, but also to China and the most powerful voices of global capital as well. There is every reason to think that profound shifts are breaking the impasse that has defined our reality for the last thirty years. This is not to say that we do not face a divided and unequal world set on a disastrous course, but rather that the key players and the terms of the negotiation are shifting.

II.

To respond to our current crisis with diplomacy is a choice with deep implications. Elsewhere, Latour has described it as the

toughest question of all, the really divisive one: do you consider that those who are on the opposite sides of the ecological issues … are irrational beings that should be … disciplined, maybe punished, or at least enlightened and reeducated? That is, do you believe that your commitment is to carry out a police- or a peace-making operation … in the name of a higher authority? Or do you consider that they are your enemies that have to be won over through a trial the outcome of which is unknown as long as you have not succeeded? That is, that neither you nor them can delegate to some superior and prior instance the task of refereeing the dispute?4

This framing comes directly from Schmitt. As does the warning that it is precisely policing actions, “wars waged in the name of reason, morality, and calculations—the ‘just’ wars … that lead to limitless extermination.”5 Their disinhibited violence is akin to that which “nature” has been subjected. What threatens us now are “Global wars waged in the name of the survival of the Globe,” which

would be much worse than the ones called “world wars.” The extent, the duration, and the intensity of such wars can be limited only if we agree that the composition of the common world has not yet been achieved, that there is no Globe. How can we decide on these limits? By accepting finitude: that of politics and of the sciences, but also of religions.6

Those are the stakes of our “diplomatic encounters.” This is why we must avoid any straining for ultimate agreement.

If we miss this fork in the path … we will find ourselves in endless wars over the utopian foundations of existence … the return of the wars of religion from which the State was supposed to protect us. … wars of religion waged in the name of protecting Nature!7

Hence the apocalyptic question that Latour puts before us is in the Gifford Lectures: “What new Thirty Years’ War” are we preparing for?8

The answer? Again Schmitt. Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth century found an answer to the unfettered wars of religion in diplomacy, framed by the “jus publicum Europaeum”—a stable order of states that accepted each other’s existence and the irreducibility of their differences and thus found a way not to eliminate war but to limit it. This, for Latour and his colleagues, is our challenge in the present: “Will the Earthbound be capable of inventing a successor to this jus publicum, in view of limiting the wars to come … what Schmitt, in his terribly precise language, called the Raumordnungskriege, the ‘wars over spatial order.’”9

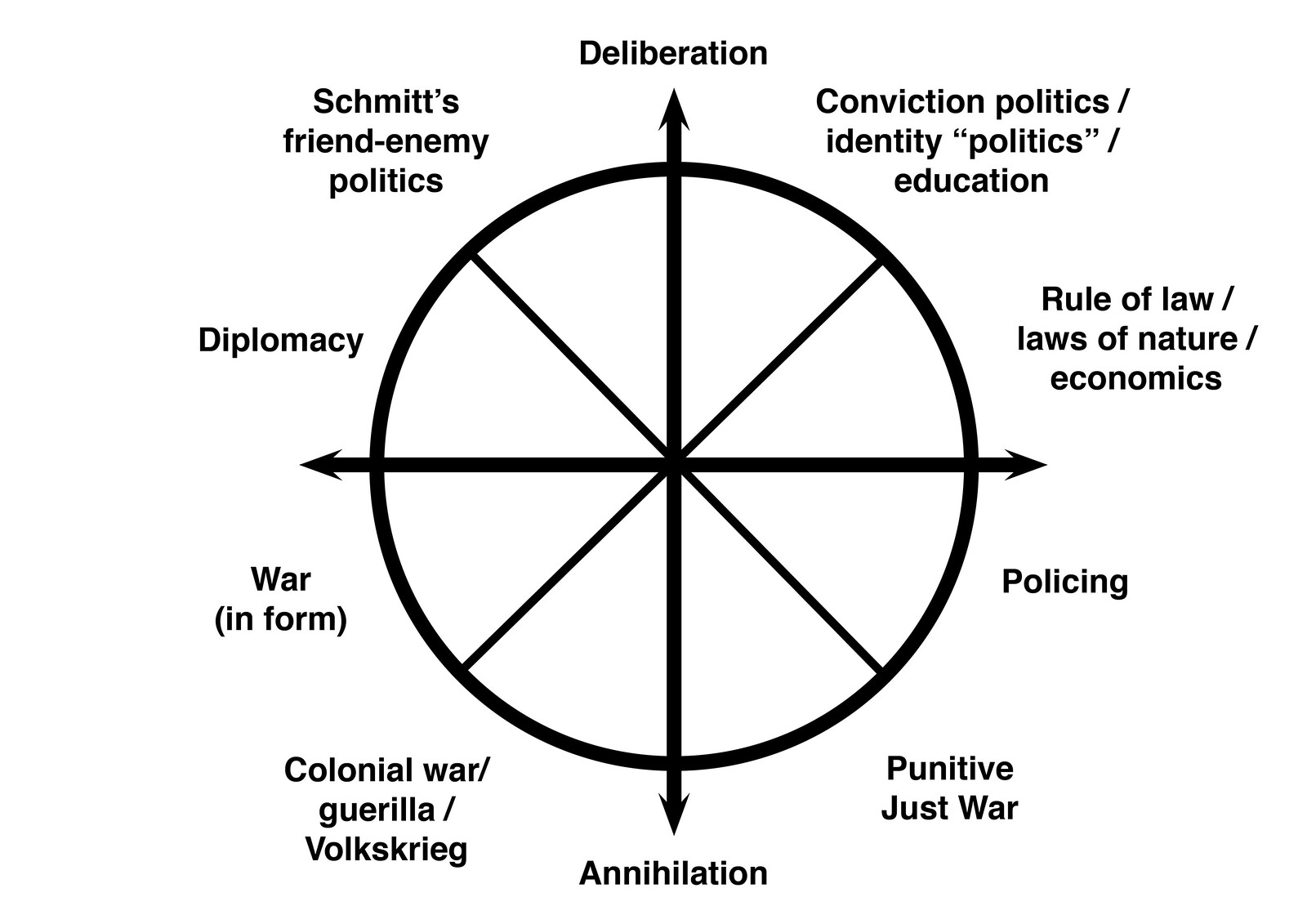

It is tempting to engage in a historical critique of Schmitt, to delve into his disastrous biography as a Nazi political theorist to expose the resentments that drive his peculiar narration of modern history. But what we need to focus on here is the sequence of plausible but unforced moves that lead to the conclusion that our current impasse should be answered principally by diplomatic, rather than (for instance) democratic deliberation, law, regulation, or police.

It is no doubt essential to recognize, with Schmitt, the way in which the triplet of politics–diplomacy–war have functioned as modes of regulating conflict in a world without a supreme arbiter. Such orders are distinct from those based on the presupposition of a superordinate sovereign, or the knowledge of natural or economic laws. It may be useful to first approximate one as an order based on a balance of power, the other on hegemony, but the next moves become problematic—first, in Schmitt’s claim that the two modes of order are radically distinct, and second, in his counterintuitive but seductive idea that the restraint of violence offered by a pluralist jus publicum Europaeum is preferable to that of founding a just order, if necessary by force. Both modes of order ultimately include war. Of course, some wars waged in the name of justice are annihilating, but not all are. And clearly not all annihilating wars are just wars. Indeed, Schmitt’s jus publicum Europaeum authorizes war as such and was secured beyond its perimeters by unfettered violence.

Schmitt is illuminating in that he forces us to confront the reality of a world without a designated arbiter. He is a resentful ideologue when he absolutizes that condition and imputes a particular bias towards unfettered violence in hegemonic projects of order. To escape Schmitt’s false alternatives, let us replace his binary oppositions by situating diplomacy in a circle of modalities of order—or perhaps a compass—that can be traveled in either direction, and which also allows cords to be drawn across, a circle that, in fact, seems far truer to the spirit of Latour and his collaborators than Schmitt’s apocalyptic polarities:

On one side you have jus publicum Europaeum, and on the other you have liberal hegemony. They are both ways of securing order, and both have their perils. But once we have gotten over the polemical rush that enables us to see the difference, we can also allow that they are not in fact radically distinct. They share a common possibility of catastrophe: a slide from either diplomacy or justice into annihilation. And we can also acknowledge that the circle closes not only at the “bottom,” but also at the “top.” There is a passage between diplomacy, politics, and lawmaking by way of deliberation and collective decision. This takes us back to the possibility rather hastily dismissed by Latour, Lin, and Guinard’s curatorial statement: “Discussion among a multiplicity of perspectives … would inevitably fall back to older models of universalism.” Let us pause for a moment on “inevitably fall back to older models.” Is that not precisely the kind of modernist gesture we are trying to get past?10 Why prejudge what will and won’t work in the future by such a simple standard of obsolescence?

The challenge is not to pick one side or the other, but to negotiate how we distribute issues around this circle of options. Schmitt had his reasons for denouncing hegemony. But why should we allow the dark historical vision of a German National Socialist traumatized by his diagnosis of a “half-century of humiliation” (to adapt the parlance used in China) to foreclose possibilities for us? Why abandon the possibility that we might travel around this circle from war by way of diplomacy, and the frank recognition of friend and foe, to deliberate on the creation, however provisional, of common rule-bound institutions? Is that not precisely the history of Europe since 1945, the place where Latour himself wishes to land? Would it not be a bitter irony to cite Carl Schmitt as we discard the idea of international justice precisely at a moment when the climate crisis truly constitutes “affected humanity” as a universal—a “bad universal,” but a universal nonetheless?11 Which brings us to escape, or exit.

III.

Recall Latour’s searing analysis of the origin of our contemporary crisis in Down to Earth:

It is as though a significant segment of the ruling classes had concluded that the earth no longer had room enough for them and for everyone else. Consequently, they decided that it was pointless to act as though history were going to continue to move toward a … world in which all humans could prosper equally. From the 1980s on, the ruling classes stopped purporting to lead and began instead to shelter themselves from the world … to get rid of all the burdens of solidarity … hence deregulation; they have decided that a sort of gilded fortress would have to be built—hence the explosion of inequalities; and they have decided that, to conceal the crass selfishness of such a flight out of the shared world, they would have to reject absolutely the threat at the origin of this headlong flight—hence the denial of climate change.12

This is not diplomatic talk. This is an indictment worthy of a climate Nuremberg. On Latour’s merciless reading, the exit-eers are the enemy of all. Those who build rocket ships signal all too clearly their intentions. Reading Latour’s chilling lines, how can one not recall Hannah Arendt’s anguished conclusion to Eichmann in Jerusalem? The ultimate charge against Eichmann was that “you supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations.”13 What was Arendt’s conclusion? Should we engage in diplomacy with people like Eichmann? Of course not. We should drag them out of their hiding places and hold them to account, even if in the dock they are capable of no more than babbling incoherent clichés.14

We cannot share the planet with the escape-ists. We will have to ban private jet travel and childish ideas about colonizing Mars, because they are not lifestyle choices but crimes against humanity. And if those who indulge in such practices have any sense, they will accept the protection of the law. The already too visible alternative is the mob justice of the likes of QAnon. Think of the lurid fantasies circulating around Jeffrey Epstein’s “Lolita Express” private plane. After all, who even needs their own private plane? What are they up to up there, all the disgraced princes and ex-presidents?

The mistake is not to treat the exponents of escape as “irrational beings that should be … disciplined, maybe punished, or at least enlightened and reeducated.” We cannot negotiate everything with everyone. Some problems can and should be delegated to the realm of law, others to economics. The mistake is to think that having done so, we have solved the whole problem. The mistake is to think that the whole crisis can be reduced to a matter of good governance rather than politics. The mistake is to conflate the parts and the whole. Having defined exit-eers as the enemies of all, we can begin negotiating the truly important questions amongst those who remain. And this means interpreting what has actually gone wrong in the last thirty years.

IV.

For obvious reasons, critiques of US climate politics focus on the scandal of climate denial. But does the preoccupation of climate campaigners with climate denial not reflect an unhealthy fixation on “climate truth”? It is too easy to conclude that if only the truth had not been so scandalously destabilized, we would have made progress. But that is not necessarily true, because it is when the doors to the exit are blocked because climate truth has been established that the seriousness of the problem actually becomes clear. Rather than being a challenge for the future, post–Paris Agreement, it has been the essential problem from the start.

The misreading is in seeing the impasse of the 1990s as defined by climate denial. Of course, Exxon and the deniers in the GOP were obstructive. But the US refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol for other reasons. The main consideration was the insistence on the part of the US Congress that any deal signed by America must be binding on everyone, notably China.

The American elite is now going through a painful reevaluation of its decisions with regard to China in the 1990s. Did they make a historic mistake in believing in “the end of history” and a political and economic convergence?15 On climate, at least, they can pat themselves on the back. They were never naive. While Angela Merkel was promoting “common but differentiated responsibilities” at COP1 in Berlin in 1995, the American negotiators, on behalf of the Clinton administration, read the situation as true diplomats and refused emotive talk about climate justice. History was not up for debate. As far as the carbon budget was concerned, the Western Landnahme was a fait accompli. They wanted to talk about the future, and you couldn’t do that without talking about China. It was China and India’s insistence that they were exempt, as non-Annex I countries, that erected an insuperable roadblock to US ratification. In climate policy America’s strategy was geo-economic from the start.

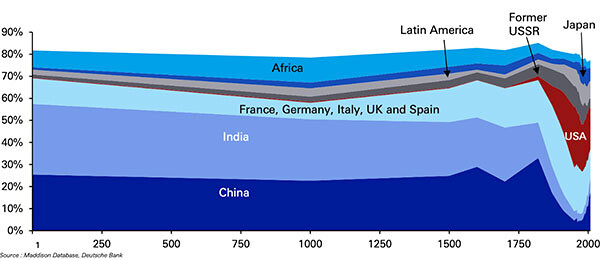

If the hockey stick of the great acceleration is the one graph that defines our current moment, the other is the Angus Maddison’s graph of global GDP:

Powershift: the historical anomaly of Western dominance in the world economy is rapidly reversing. Shares of global GDP on purchasing-power parity basis.

You can neutralize the drama of this graph by arguing that it displays the natural effect of globalization and convergence. But what marks our moment is precisely that a naive story of convergence has tipped into a historic crisis of multipolarity. The moment of Western hegemony was a parenthesis. You cannot do justice to the “paradoxical unity” of our current moment, and to the terms of diplomatic negotiation, without incorporating this historic shift in the global balance of power.

If the truly decisive destabilization of the moment is that nature no longer serves as an outside to politics, the secondary destabilization arises from the fact that second nature, i.e., the economy, has begun to destabilize the order of states. It is not just that economic crises like that of 2008 and 2020 require interventions by the state. Even when the world economy functions well—or particularly when it functions well—combined and uneven growth challenges the existing structure of state power. This is the “jealousy of trade” problem that goes back to the eighteenth century, for which liberalism was supposed to be the antidote. But liberalism always operated on an unspoken assumption. The reason that global economic growth could be regarded as a universal blessing was that it did not disturb the delicate global order, anchored first by British and then by American global hegemony. In the last ten years that confidence has collapsed. It is not just blue-collar populism, but the Pentagon as well, that is skeptical about globalization.

This is where diplomacy, in the most classical sense, becomes absolutely the order of the day. But the next question is how to characterize the players.

V.

In a recent dialogue with Latour, Dipesh Chakrabarty has insisted that, along with Eurocentric projects of modernization, we must recognize India and China as exponents of “a regime of planetarity of the anti-colonial, modernizing imagination, an imagination that acknowledged its debt to Europe in a full-throated manner and yet asserted its sovereign, anticolonial values. Humanocentric, yes, but resolutely anti-imperial.”16

Chakrabarty’s point is well taken. But his category of emancipatory planetarity obscures the radical differences between India and China that the project of subaltern studies was once so attentive to. China’s regime today was forged by total war and social and economic revolution. It was stabilized by a strategic alliance with the US and by the violent repression of Tiananmen. It was the site not just of the Cultural Revolution, but, as recently as the 1980s, of the most massive biopolitical experiment in human history, the one-child policy. It then became the theater for the most radical burst of economic growth and material transformation in the history of our species. Those uncooperative Americans at Kyoto in 1997 were right about one thing: the world was on the cusp of another great acceleration and it was all about China.

But here is the real surprise. If it was tempting for parts of America’s ruling class to square deregulation, inequality, and climate denial in a strategy of escape, why was that not the obvious choice for the Chinese elite too? At first, the climate justice argument was crucial in allowing them to “own” the issue as a means of critiquing the West. But Copenhagen in 2009 marked the end of that road. Chinese emissions were surging ahead of those of the US. The US insisted on a deal. The meeting ended in chaos. This was the moment in which Beijing could have denounced climate politics as a Western conspiracy.17 There was a brief spluttering of nationalist indignation. But then China’s climate skeptics fell silent, perhaps through censorship or through lack of conviction. First Beijing signed up to Paris, and then on September 22, 2020, came Xi Jinping’s announcement to the UN General Assembly: climate neutrality by 2060.

We may never know precisely what happened, but let us conjecture a mirror image to Latour’s speculation about 1980s America. One can imagine a conversation in Beijing that went something like this: “The CCP is about to enter its second century. In the face of the coronavirus, we have demonstrated the superiority of our mode of rule. We are stamping our will on Xinjiang. We are ending ‘one country, two systems.’ The great threat to our rule is actually the floods, desertification, and the ominous water shortages. We hold in our hands control over much of the climate equation. Through the Belt and Road Initiative we are building energy infrastructure across 126 other countries. The decision is obvious. To paraphrase comrade Lenin, the future is Xi Jinping Thought plus electrification.”

Xi’s declaration to the UN General Assembly has revealed that the entire process has, in fact, been waiting on China. For the first time since the advent of global climate talks, the major emitter is aligning with the agenda of decarbonization. Now, finally, the real talks can begin.

But how will others respond?

VI.

As Latour remarked, Europe didn’t deserve its second chance as the principal laboratory for the discovery of terrestrial limits.18 It didn’t deserve it and it hasn’t lasted long—provincialized Europe has been provincialized once more. Let us hope that the Europeans take it well.

More important is the American response. At the time of writing, Biden’s victory may involve a return to the modest green agenda of the Obama era. But we may need to look to other points on the circle to understand the most important shift for the US, since electoral politics could matter less than markets.

Back in 2015, Latour was struck by the remarkable moment when Mark Carney, the then-governor of the Bank of England, warned key financial institutions: “Please, please check what will happen to all these big investments if the Paris meeting gets to 2 degrees, because those investments will be worth nothing.” The problem was not a shortage of oil, but finding yourself lumbered with trillions in stranded assets. This, Latour declared, “is where the nomos arrives, because it’s a matter of legal terms and concepts, arriving on to a physical resource which is plenty, and limited not by its objective limits … but by something which represents this future … jus communis.”19

In the five years since, the argument has moved on. In the week before Xi Jinping’s speech to the UN, Climate Action 100 Plus, a lobby group whose members represent global investors with a collective $47 trillion in assets, announced that it would be judging 161 of the largest companies, collectively responsible for up to 80 percent of global industrial greenhouse gases, by their progress towards net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.20 Of course, there is an element of corporate greenwashing in any such statement. But it can also be read as a vote by giant asset managers like BlackRock and Pimco against escape. Like Beijing, they agree that the status quo and the future accumulation of capital depends on maintaining a stable environmental envelope. As for Beijing, the risks are political as well as physical. In the event of future climate crises, firms that might be seen as recklessly endangering climate stability may be at risk of suddenly losing their license to operate. Politics might intervene. Laws and regulations would follow.

None of this adds up to a consolidated, consensual image of a single world on which we all agree. In many realms, there is no designated arbiter. But Latour’s Gaia is making its force felt. Agreements like Paris are beginning to exercise a subtle but significant sway, not because they stand metaphysically above the world, but because they have authority—the daily climate news confirms that we made them for a good reason and powerful actors are committed. Let us look for every chance for “diplomatic encounters.” But let us reckon with the pervasive force of the emergency that our instruments so clearly register, and let us not ignore complementary action on all points of the compass of ordering mechanisms.

See “Coping with Planetary Wars” in this issue.

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Harvard University Press, 2012).

Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (John Wiley & Sons, 2018). Où atterrir? Comment s’orienter en politique (Éditions La Découverte, 2017).

Bruno Latour, “War and Peace in an Age of Ecological Conflicts,” Revue juridique de l’environnement 39, no. 1 (2014): 51–63.

Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime (John Wiley & Sons, 2017), 285.

Latour, Facing Gaia, 285.

Latour, Facing Gaia, 285.

Latour, Facing Gaia, 187.

Latour, Facing Gaia, 284.

See Bruno Latour and Dipesh Chakrabarty, “Conflicts of Planetary Proportions—a Conversation,” in “Historical Thinking and the Human,” ed. Marek Tamm and Zoltán Boldizsár Simon, special issue, Journal of the Philosophy of History 14, no. 3 (2020) →.

See Bruno Latour, “Issues with Engendering,” interview by Carolina Miranda, tran. Stephen Muecke →. Originally published in French in Revue du crieur, no. 14 (2019).

Latour, Down to Earth, 1–2, 18–19.

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Penguin, 2006), 279.

See Judith Butler, “Hannah Arendt’s Death Sentences,” Comparative Literature Studies 48, no. 3 (2011): 280–95.

See Adam Tooze, “Whose Century?” London Review of Books 42, no. 15 (July 2020) →.

Latour and Chakrabarty, “Conflicts of Planetary Proportions.”

See Geoff Dembicki, “The Convenient Disappearance of Climate Change Denial in China,” Foreign Policy, May 31, 2017 →.

Latour, Down to Earth, 106.

Bruno Latour, “Bruno Latour Encounters International Relations,” interview by Mark B. Salter and William Walters, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, April 19, 2016 →.

Attracta Mooney, “Influential Investor Group Demands ‘Net-Zero’ Targets,” Financial Times, September 14, 2020 →.