What does human nature consist in and, beyond it, what is life? What makes us moral beings? What is our destiny on earth? For a very long time, only theologians, metaphysicians, and philosophers of existence seemed to concern themselves with such questions.

Odd as it may seem, today they are back, including and especially among scientists. The meditation on how life ends has only increased in intensity in the context of the coronavirus lockdowns and the ever-rising death toll.

But whereas in the past it was a matter of determining whether the human was above all body or mind, today the debate is about whether it is matter and matter alone, or if, in the end, it is merely a sum of physical and chemical processes.

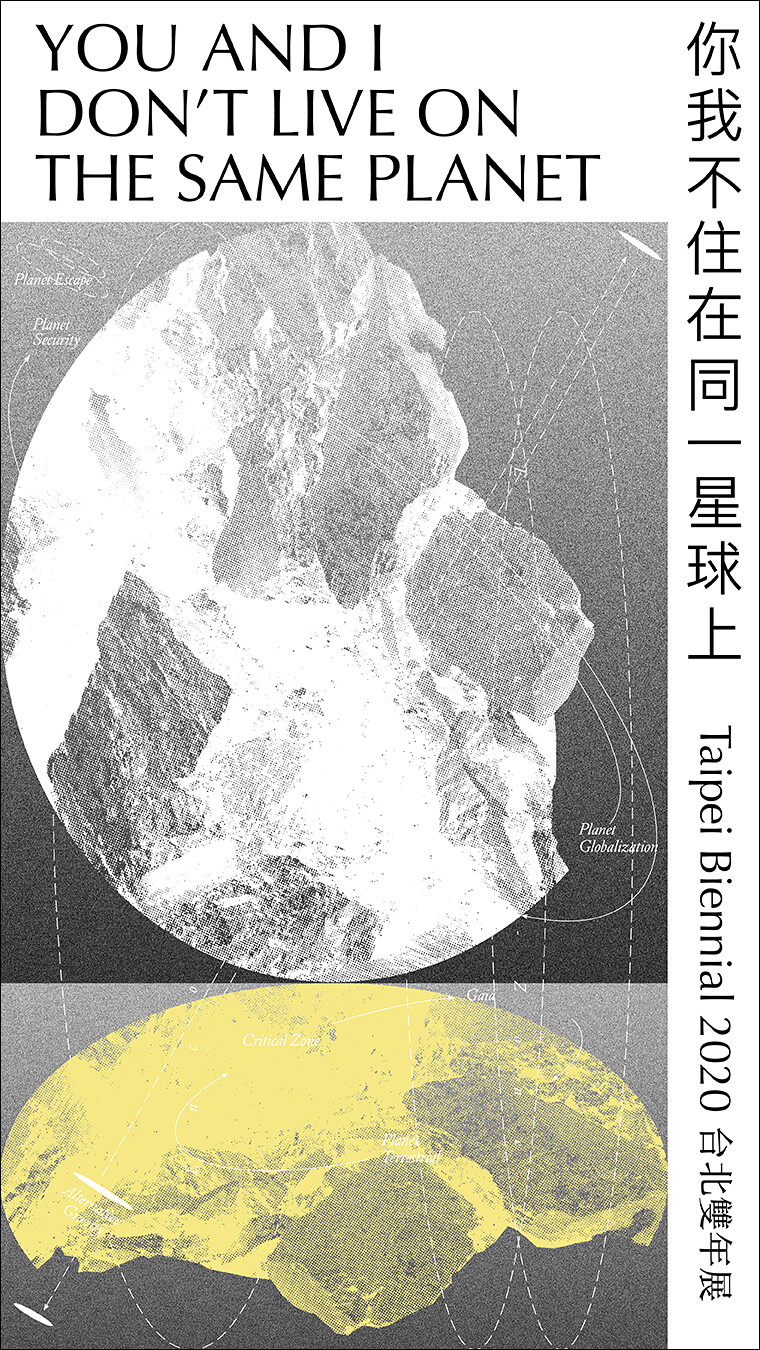

The discussion is also about what the futures of life can be in the age of extremes, and the conditions under which life ends.

Body, matter, and life are three very distinct concepts. One need not embrace Christianity to understand that, in every human body, in its organic unity, there is something that is not solely matter. To this something, several names have been given by different cultures and in different eras. But whatever the cultural differences, the truth of the human body will have been to resist any reductionism.

The same is true of what could be called the body of the earth, and even its flesh. The body of the earth is recognizable in its profusion. Typical of this is the viral eruption that we are currently experiencing on a planetary scale.

In the eyes of many, this virus is a demonstration of nature’s virtually infinite power. They see in it an event of cosmic portent, a harbinger of disasters to come. For others, it is the logical outcome of the project of a Godless world, which they accuse modernity of having initiated. For them, this world, supposedly free but in actuality left to its own devices and with no recourse, has done nothing but subjugate humans under the constraint of a nature that is now converted into an arbitrary power.

In fact, God’s absence is hardly what characterizes today’s world. Neither is God’s virulent and vengeful presence, in the form of the violence of a virus or other natural calamities, the distinctive features of our times. The hallmark of the beginning of the twenty-first century is the swing into animism.

Coupled with technological escalation, the transformations of capitalism have led to a twofold excess: an excess of pneuma (breath) and an excess of artifacts, the transformation of artifacts into pneuma (in the theological sense of the term). Nothing translates this excess better than the techno-digital universe that has become the double of our world, the objectal embodiment of the pneuma.

The distinctive characteristic of contemporary humanity is to constantly traverse screens and be immersed in image machines that are at the same time dream machines. Most of these images are animated. They produce all kinds of illusions and fantasies, starting with the fantasy of self-generation. But above all they enable new forms of presence and circulation, incarnation, reincarnation, and even resurrection. Not only has technology become theology, it has become eschatology.

In this universe, it is not only possible to split oneself into two or to exist in more than one place at a time, and in more than one body or in more than one flesh. In fact, it is also possible to have doubles, i.e., other selves, a cross between the person’s own body and the image of the person’s body on the screen. Moreover, traversing screens has become the primary activity of contemporary humanity. It authorizes us to exit bodily boundaries and inaugurates the plunge into all sorts of parallel worlds, including the beyond, without a safety net. In being transported to the other side of the screen, humanity can be present to itself while simultaneously keeping a distance from itself.

Contemporary animism is, moreover, the result of a vast reconfiguration of the human and its relationship with the living. The era of the second creation has thus begun. It is now a matter of technologically capturing the energy of the living and downloading it into the human, in a process that calls to mind the first creation. This time, however, the project is to transfer all the attributes of the living into organo-artificial components endowed essentially with the characteristics of the human person.

These components are called upon to operate as human doubles. While in the past animism was considered a relic of the obscurantism of so-called primitive societies, now it is now compatible with artificial intelligence, supercomputers, nanorobots, artificial neurons, RFID chips, and telepathic brains.

This second creation, however, is basically profane. It proceeds via a threefold process of decorporation, recorporation, and transcorporation that instrumentalizes the human body in an attempt to turn it into a vehicle of hybridization and symbiosis. This threefold process is sacramental. It is the cornerstone of the new technological religions. It appropriates the fundamental categories of the Christian mystery, the better to destabilize them, beginning with creation itself, the incarnation, the transfiguration, the resurrection, the ascension, and even the Eucharist (this is my body).

With the cybernetization of the world, both the human and the divine are downloaded into a multitude of tech objects, interactive screens, and physical machines. These objects have become genuine crucibles in which visions and beliefs, the contemporary metamorphoses of faith, are forged. From this standpoint, contemporary technological religions are expressions of animism. But they also differ from it inasmuch as they are governed by the principle of artifice, whereas ancestral animism was governed by that of vital force.

Indeed, in ancestral animism, neither body nor life existed without air, without water, and without a common ground. In African precolonial systems of thought, for instance, life and body, and consequently the human, were fundamentally open to air and to breath, to water and to fire, to dust and to wind, to trees and to their vegetation, to animals and to the nocturnal world. Everything was alive, at the intersection of languages. This essential porosity was what made for its essential fragility. It was thought that the human adventure on earth was played out in the reality of air and breath. This could only last if a place was made for the regeneration of vital cycles. Life consisted in assembling together absolutely everything. It was a matter of composition and not excessiveness.

As the birthplace of humanity, Africa has perhaps experienced more catastrophic forces than other parts of the globe. It has learned from this that catastrophe is not an event that happens once and for all, and then goes away after having accomplished its gruesome work, leaving a world of ruins in its wake. For many peoples, it has been a never-ending process, which accumulates and sediments.

Under these conditions, opening channels for a more breathable world could be the foundation of a new ethic in the viral age. For the viral age is the corollary of the Anthropocene, the irreversible transformation of environments and the expansion of a new form of colonialism: techno-molecular colonialism.

The age of brutalism—that is, of forced entry—it is an age in which dream machines and catastrophic forces will become increasingly visible actors of history. The air we breathe will be more and more laden with dust, toxic gases, substances and waste, particles and granulations—in short, with all kinds of emanations. Instead of exiting the body thanks to immersive visualization technologies, the point will then be to return to it, especially through the organs that are most exposed to asphyxiation and suffocation.

To return to the body is also to come back to earth, understood not as a land, but as an event that, in the end, fundamentally defies the boundaries of states. Understood in this way, the earth belongs to all its inhabitants, without distinction of race, origin, ethnicity, religion, or even species. It pays no attention to the blind individual or to the naked singularity. It reminds us how much each body, human or otherwise, however singular it may be, bears on and in itself, in its essential porosity, the marks not of the diaphanous universal, but of commonality and incalculability.

Translated from the French by Gila Walker.