For Bruno

1.

When did things start to go wrong? It is hard not to ask that question nowadays. By “things” we mean, of course, “nous autres,” those civilizations that are now known to be mortal, as Valéry lamented in 1919, using a plural to speak of a singular, modern European civilization, whose future was the object of his deep concern. Today, this singular has become even more evidently and disturbingly a universal, the techno-spiritual monoculture of the species. For this singular form (in the double sense of the adjective) of civilization, which for many centuries saw itself as “the origin and goal of history,” is faced with the possibility of being at the threshold of a not very original “goal”: self-extinction, caused by the cancerous metastasis of its techno-economic matrix and the cosmological imaginary that sustains it, in other words, of its cosmotechnics and cosmopolitics, in Yuk Hui’s sense.1

The Origin and Goal of History is the title of the famous book in which Karl Jaspers advances the concept of an “Axial Age,” the period after which the species would begin to have not only a common history but also a single destiny.2 With this term Jaspers referred to the period between 800 and 200 BCE, during which Eurasia saw the rise of Confucius, Lao-Tse, Buddha, and Zoroaster, the great Hebrew prophets, and the Greek poets, historians, and philosophers. In this period, “Man, as we know him today, came into being.”3 All pre- or extra-axial cultures were gradually absorbed by the axial cultures, on pain of disappearing; in the twentieth century, Jaspers believed, the last “primitive” peoples were finally heading towards extinction.

2.

We do not recognize ourselves in pre-axial humanity, ancient or contemporary; the great archaic empires are like another planet to us. “We are infinitely closer to the Chinese and the Indians than to the Egyptians and the Babylonians”—which did not prevent the author from underlining a certain “specific quality of the West.”4 According to him, the Axial Age created a universal “We” de jure, but only in the techno-scientific modernity inaugurated by the “Teuto-Romance peoples” did this “We” become a de facto universal, “the really universal, the planetary history of mankind.”5

Robert Bellah, one of the historians of culture who took Jaspers’s thesis on board, suggests that, to this day, “we” live off the heritage left by the Axial Age:

Both Jaspers and Momigliano say that the figures of the axial age—Confucius, Buddha, the Hebrew prophets, the Greek philosophers—are alive to us, are contemporary with us, in a way that no earlier figures are. Our cultural world and the great traditions that still in so many ways define us, all originate in the axial age. Jaspers asks the question whether modernity is the beginning of a new axial age, but he leaves the answer open. In any case, though we have enormously elaborated the axial insights, we have not outgrown them, not yet, at least.6

The following pages express our suspicion that the final words of this reflection—“we have not outgrown them, not yet, at least”—may be fatally wrong, or rather, they can only be considered true if interpreted in a pessimistic light, as they seem to justify Latour’s admonition that “there is no greater intellectual crime than to address with the equipment of an older period the challenges of the present one.”7

3.

Let us accept, for the sake of the argument, the admittedly controversial thesis of the historical occurrence of an “Axial Age,” or at least of its typological value.8 The hypothesis we present to our readers is the following: the advent and popularization, from the first decade of the century, of the concept of the Anthropocene reveals the terminal obsolescence of the theological-philosophical equipment bequeathed by the Axial Age. And this for the same reasons that made it, as Bronislaw Szerszinsky wisely observed, a “harbinger” of the Anthropocene epoch—which, as is well known, began well before it received a name.9 In other words, if the epoch of the Anthropocene had among its conditions of possibility the cultural mutations that occurred in Eurasia about three millennia ago, the concept of the Anthropocene, insofar as it names a “total cosmopolitical fact” (in Mauss’s sense)—an ecological catastrophe, an economic tragedy, a political threat, religious turmoil—indicates the extreme difficulty we, with our axial repertoire, have in thinking about the epoch these mutations prepared. For Jaspers’s “truly universal” history (again, an exclusively human universal) has become the “negative universal history” of the Anthropocene,10 a time whose name equivocally refers to that “Man, as we know him today.” The ánthrōpos of the “Anthropocene” is the character that came into being in the Axial Age.

It might therefore be necessary to go much further back than usual in theorizing about the causes and conditions of the Anthropocene, as far as the frontier between the axial revolution and the worlds that preceded it, many of which, incidentally, insist on continuing to exist in various parts of the world, even if increasingly harassed by the self-appointed emissaries of ánthrōpos. While the immediate material causes of the Anthropocene have emerged much more recently—let us summarize them with the expression “fossil capitalism”—the anthropological configuration articulated in the Axial Age is at the center of the intellectual conditions of possibility (spiritual or subjective conditions, if you will) of those objective conditions, and in particular of the conviction of the “destinal” nature of the latter.11

4.

There is no room here for a review of all the characteristics of what many historians have called the “axial breakthrough”—among which is the very idea of a breakthrough, of a radical break with the past, in short, the germ of the modern idea of revolution (and, of course, of our own suggestion as to the obsolescence of the axial inheritance). Let us just highlight some of the expressions that would define the “common underlying impulse in all the ‘axial’ movements”:12 “the step into universality”; “the liberation and redemption of the specifically human in man” (Jaspers); “the age of transcendence”; “a critical, reflective questioning of the actual and a new vision of what lies beyond” (B. Schwartz); “the age of criticism” (A. Momigliano); “a leap in being”; “the disintegration of the compact experience of the cosmos” (E. Voegelin); the emergence of “second-order thinking” (Y. Elkana); “theoretic, analytic culture” (M. Donald, R. Bellah); “the negation of mythical authority” (S. Eisenstadt); the “power of negation and exclusion”; “the antagonistic energy” of the axial “counter-religions” (J. Assmann); “the passage from immanence to transcendence” (M. Gauchet). Last but not least, let us remember “the progress in intellectuality” that Freud, in the wake of Kant, saw in Jewish iconoclastic monotheism, and the “disenchantment of the world” of Weberian fame, extended back by M. Gauchet and C. Taylor to the Axial Age and the advent of counter-religions of transcendence, seen as necessary steps in the process of the secularization of human cultures.

5.

It is not difficult to notice that these definitions look a lot like the image modernity has made of itself. Although tinged with greater or lesser ambivalence (particularly marked in Assmann and his theory of “Mosaic distinction”), they are essentially positive, identifying in the Axial Age the initial step in the long march towards the emancipation—the master word of modernity—of humanity from a primitive condition of magical immanence, dominated by a fusional relationship with the cosmos, a narcissistic and anthropomorphic monism, a submission to the past, a mythical freezing of the social order. A condition of ignorance, in short, if not structural denial, of the species’ infinite potential for self-determination, both in terms of its sociopolitical institutions and its technical capacity to deny natural “givens.” The evolutionist parti pris of most authors is obvious, and the assumption of the inexorable irreversibility of the “breakthrough” is practically unanimous. Perhaps it is also no coincidence that several of the most important “axialists” show a political and theoretical orientation more to the right than to the left.13

6.

The Great Attractor of this ideological constellation is, of course, “transcendence,” an idea that counter-invented its own antipode, “immanence.” The concept of transcendence, as is well known, is at the center of Jaspers’s existential philosophy; but it is mobilized in less specific directions in most references to the Axial Age. The invention of transcendence is generally defined as the establishment of a hierarchical disjunction between an extramundane and a mundane order, and the consequent emergence of an ontological dualism that will mark all post-axial thinking. It is the result of a conjunction, in the middle of the first millennium BCE, of political and cultural tensions and conflicts that led to an anxious relativization of the mundane order in all its aspects, which in turn stimulated the elaboration of a conceptual metalanguage (critical reflexiveness, second-order thinking) and fostered the compensatory search for an absolute foundation and a salvational horizon, both of them located on the extramundane plane. What marks human history from the Axial Age onwards would then be the emergence of transcendence as a supersensible and/or intelligible dimension that harbors a higher, non-apparent Truth, with a personal (the God of the Abrahamic religions) or impersonal (Parmenidean Being, modern Nature) essence. In some versions of the axial revolution, transcendence has come to assume the form and order of time—as in the case of Christianity and its many modern philosophical heirs—to the point that space is regarded as the pagan (hence untrue) dimension par excellence: “The truth of space is time” (Hegel).14 It is no surprise that this metaphysical negligence of spatiality would have serious consequences for our present mixture of impotence and indifference in the face of the Anthropocene, that is, our seeming inability to move from the “truth of space” to truth in space. But we anticipate.15

7.

A recently published historical study by Alan Strathern, Unearthly Powers, takes as its starting point the dichotomy, explicitly derived from the axialist literature, between two forms of religiosity, which he calls “immanentism” and “transcendentalism.”16 The specific problem of this well-documented monograph will not occupy us here, namely, the interaction between political and religious factors that led to the worldwide expansion of some major transcendentalist religions (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism). But its treatment of the concepts of transcendence and immanence was one of the inspirations for the present text.

Strathern advances three main theses to support the historical analyses developed in Unearthly Powers. Firstly, in an uncompromisingly “naturalistic” position, the author defends the idea that immanentism is our default religious mode, resulting from certain “evolved features of human cognition.”17 It is part of the natural culture of the species, the “ontotheological” moment of pensée sauvage. It follows that immanentism itself is originally immanent: recursively immanent, therefore, at least until it is reflexively reappropriated by certain philosophical and political counter-axial traditions. Secondly, transcendentalism, due to its paradoxical, life-denying character (as Nietzsche would say), its contradiction with the basal metabolism of the human mind (as Strathern would say), has always manifested itself in an unstable synthesis with immanentism, constrained to establish compromises with it. The synthesis was achieved in various forms in the post-axial religions; it gave rise, for example, to different categories of mediators between the two orders, ontologically ambiguous or hybrid figures: prophets, priests, ascetics, philosophers, messiahs. The foundational dogma of Christianity is one of the responses to this need for a bridge brought about by axial disjunction: the earthly and suffering incarnation of God or Logos, the radical immanentization of supreme transcendence. The thesis of an unstable religious synthesis takes up Shmuel Eisenstadt’s idea that the Axial Age establishes an “irresolvable tension” between affirmed (revealed, announced) transcendence and the dogged persistence of worldly immanence, the immovable substratum of humanity’s trajectory as a living species. Finally, if we understand Strathern’s argument correctly, the worldwide success of a form of religiosity as “unnatural” as transcendentalism is due to its capture by a historical phenomenon that originates independently, to wit the State, by facilitating the commensurability between religious truth and political power as a separate instance of the socius—a commensurability that is particularly evident in the elective affinity (the “intriguing associations”18) between monotheism and empire. The homology between structures of transcendence and political institutions, however, is not restricted to the premodern world: think of the “cosmopolis” of the seventeenth century analyzed by Stephen Toulmin, in which the Newtonian laws of Nature and the principles of the absolutist nation-state justify and legitimize each other.19

8.

For Jaspers and most axialists (certainly not for Strathern), the invention of transcendence and everything that followed is part of a necessary progress of humanity, the unfolding of the potentials that distinguish it within nature as whole. All converge, however, in the realization, reaffirmed in Unearthly Powers, that there is no continuous linear advance from original immanence to final (or terminal) transcendence, but that post-axial history shows a certain alternating rhythm, as the innovative impulses of transcendentalism are gradually neutralized by immanentist inertia, in a kind of fractal, entropic routinization of charisma—the well-known relapses into idolatry, ritualism, and superstition, the atavistic paganism of the popular classes—and require periodic efforts in reform, asceticism, and purification, the old idea of starting anew. (Would this mean that the transcendentalist scheme of time’s arrow is historically subject to the immanentist idea of time’s cycle?20)

9.

The dialectics between transcendence and immanence unleashed by the axial paradigm took the canonical form, in modernity, of the distinction between Nature and Culture, whose notorious instability became increasingly unsustainable as the “total” cosmopolitical implications of the Anthropocene emerged. This instability appeared particularly in the contradictory alternation of the predicates of transcendence and immanence between the orders of Nature and Culture (or Society), as Latour showed masterfully in We Have Never Been Modern.21 Now Culture was the new name for human transcendence (the soul of divine origin modernized and internalized as practical reason or as the order of the Symbolic) and Nature that of its immanence (the congenital animality of the species, from the instinctive to the cognitive plane). Now Culture was the domain of immanence (openness to the world, history as the history of freedom, the heroism of the denial of the Given) and Nature that of transcendence (the exteriority and intangibility of physical and biological legality, history as the mechanical evolution of the cosmos). The meanings of the notions of transcendence and immanence are, moreover, mutually interchangeable—in the above characterization, we could have flipped them—depending on whether what one emphasizes is a primary immanence of Culture to Nature, which then assumes the all-embracing mantle of transcendence (a neo-transcendentalist position, like Strathern’s on immanentist religiosity22), or a secondary immanence of Nature to Culture, which becomes a para-transcendent power to infuse meaning into reality (a neo-immanentist position). This is due to the frequent ambiguity in the way this pair of concepts is used, either associating transcendence with a spiritual or ideal order and immanence with the corporal and material order (ontological transcendence, the opposition between the celestial and the terrestrial), or, inversely and more modernly, associating transcendence with objective exteriority and immanence with subjective interiority (epistemological transcendence, the opposition between the world of things and what is given to experience).23 We qualified as “primary” the subsumption of Culture by Nature and as “secondary” the inverse one because, in modernity, what linguists would call the “unmarked” pole of the opposition is Nature—Culture being the diminished secular successor of the extramundane order of Grace, which in the premodern world encompassed the mundane order (without, however, being able to abolish it). This inversion in relation to the premodern axial regimes is explained by the phenomenon of the “secularization” or “disenchantment” of the world.

10.

The syntheses of the pre-axial period lost their already quite relative balance with the translatio imperii24 that established the sovereignty of the pole of Nature and gave it eminent dominion over the order of Culture; the late socio-constructivist reactions to this turnaround failed to really mobilize the hearts and minds of the moderns. The transcendent character of the extramundane (“religious”) order was absorbed by the mundane (“scientific”) order, creating modern Nature as an absolute ontological domain, “exterior, unified, deanimated, indisputable.”25 The old supernatural values were confiscated by this new and true “Super-Nature.” The fundamental gesture of modernity, thus, is the spillover of Assmann’s “Mosaic distinction” of transcendence into immanence—an immanence that has completely lost the characteristics it possessed in the pre-axial worlds, and that it still retained residually in the post-axial worlds, namely, its “compact experience of the cosmos” (Voegelin), its democratic universalism (Strathern), its contempt for monotheistic intolerance (which later became the mono-naturalist intolerance of the moderns), its pragmatic skepticism towards “Mosaic” certainties (Assmann) and the foundational dichotomies consecrated by the gospel of transcendence, such as those between body and spirit, human and extra-human, subject and object, people and things. This first immanentization of transcendence, which began in the seventeenth century, the era of the “Search for Certainty,”26 in reaction to the successive crises of the unstable synthesis (the immanentism and skepticism of the Renaissance, Copernicus and Galileo, the wars of religion), will manifest itself differently in the following centuries, this time spilling over from the domain of Nature to that of Culture—to various trends in philosophy, political theory, and forms of religiosity.27 On the other hand, and crucially, the immanentization of transcendence as Nature has metaphysically deterritorialized Culture (which lost its religious ballast and became a sort of free-floating domain), causing the liberation or “disinhibition”28 of powerful sociocultural forces which, precisely because they are “natural” in the sense of ontologically continuous with the material environment over which they apply (the earth’s energy cycle, the biosphere), have caused what has been called the Anthropocene.

11.

The definitive, and in more than one sense, “final” failure of the modern ideologeme of Nature and Culture signals the passing of the conceptual heritage of the Axial Age. Strictly speaking, this failure means the end of any hope in a real transcendence: no God will come to save us. Are we then reduced to accepting a definitive immanentization of transcendence, with the triumphant disenchantment of the world, the end of humanity’s childhood (or its prehistory, Marx would say), that is, political mastery of society and technical sovereignty over the planetary (and interplanetary) environment? Or, in the face of the awakening to Gaia’s “cosmological state of exception” (Gaia the improbable planet made by what it makes, to wit Life), should we embark on a reflexive transcendentalization of our “old anthropological matrix”29—a “compact” immanence—attempting an intensive reanimation of the local cosmos (the earth) by means of a counter-axial re-enchantment of the world, necessarily secondary and somewhat strained? This dilemma gets even more complicated when we realize that the appeal of certain proposals for the transcendentalization of immanence, such as the theology of “happy sobriety”—an especially authoritative formulation30 of the human need to convert necessity into virtue—seems to be rather powerless in the face of the “anthropological” appeal of some religious reappropriations of the immanentization of transcendence, such as the neo-Pentecostal theologies of prosperity, or, more seriously, in the face of the irrefutable demand for material emancipation by the dispossessed masses?31

12.

Let us conclude with a return to Hegel’s quote above: “The truth of space is time.” It encapsulates the whole meaning of the philosophy of history that originated in the Axial Age, and whose most successful Western fruit was Christianity and its diffuse cultural heritage. It is no accident that it reappears almost literally in a programmatic document by Pope Francis, a pope nevertheless extremely sensitive to the (“spatial” by definition) cause of the earth. In the exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, Francis establishes four principles that underlie every possibility of “peace, justice and fraternity.” The first one is precisely: “Time is greater than space.” The subsequent comment exhorts patience and warns that

giving priority to space means madly attempting to keep everything together in the present, trying to possess all the spaces of power and of self-assertion; it is to crystallize processes and presume to hold them back. Giving priority to time means being concerned about initiating processes rather than possessing spaces. Time governs spaces.32

In the Pope’s encyclical Laudato Si’, a document whose eco-political significance cannot be overestimated, we find another admonition, this one regarding the deviations that threaten all well-meaning condemnations of anthropocentrism: “Our relationship with the environment can never be isolated from our relationship with others and with God. Otherwise, it would be nothing more than romantic individualism dressed up in ecological garb, locking us into a stifling immanence.”33

The superiority of time is thus what allows ánthrōpos to escape the immanence seen as a prison.34 The “integral ecology” of Francis respects, notwithstanding his admirable effort to bring the cause of the earth to the center of the concerns of the faithful, the absolute doctrinal principle of the salvational relationship between temporality and extramundanity, a relationship that extracts, partially but decisively, the human species from earthly immanence and distinguishes it within Creation.

It is then appropriate to repeat here Latour’s concern about the contribution of this unilateral privilege of time, which we find in the philosophies of history, to the indifference or blindness of “nous autres, civilisations” regarding the cosmopolitical challenge of the Anthropocene: “Could this civilization’s blindness actually be caused in part by the very idea of ‘having’ a philosophy of history?”35 And he concludes, in a tone that we should say is more desiderative than constative:

It seems that everything happened as if the orientation in time was so powerful, that it broke down any chance of finding one’s way in space. It is this deep shift from a destiny based on history to an exploration of what, for want of the better term, could be called geography (actually Gaiagraphy), that explains the rather obsolete character of any philosophy of history. Historicity has been absorbed by spatiality; as if philosophy of history had been subsumed by a strange form of spatial philosophy—accompanied by an even stranger form of geopolitics (actually Gaiapolitics).36

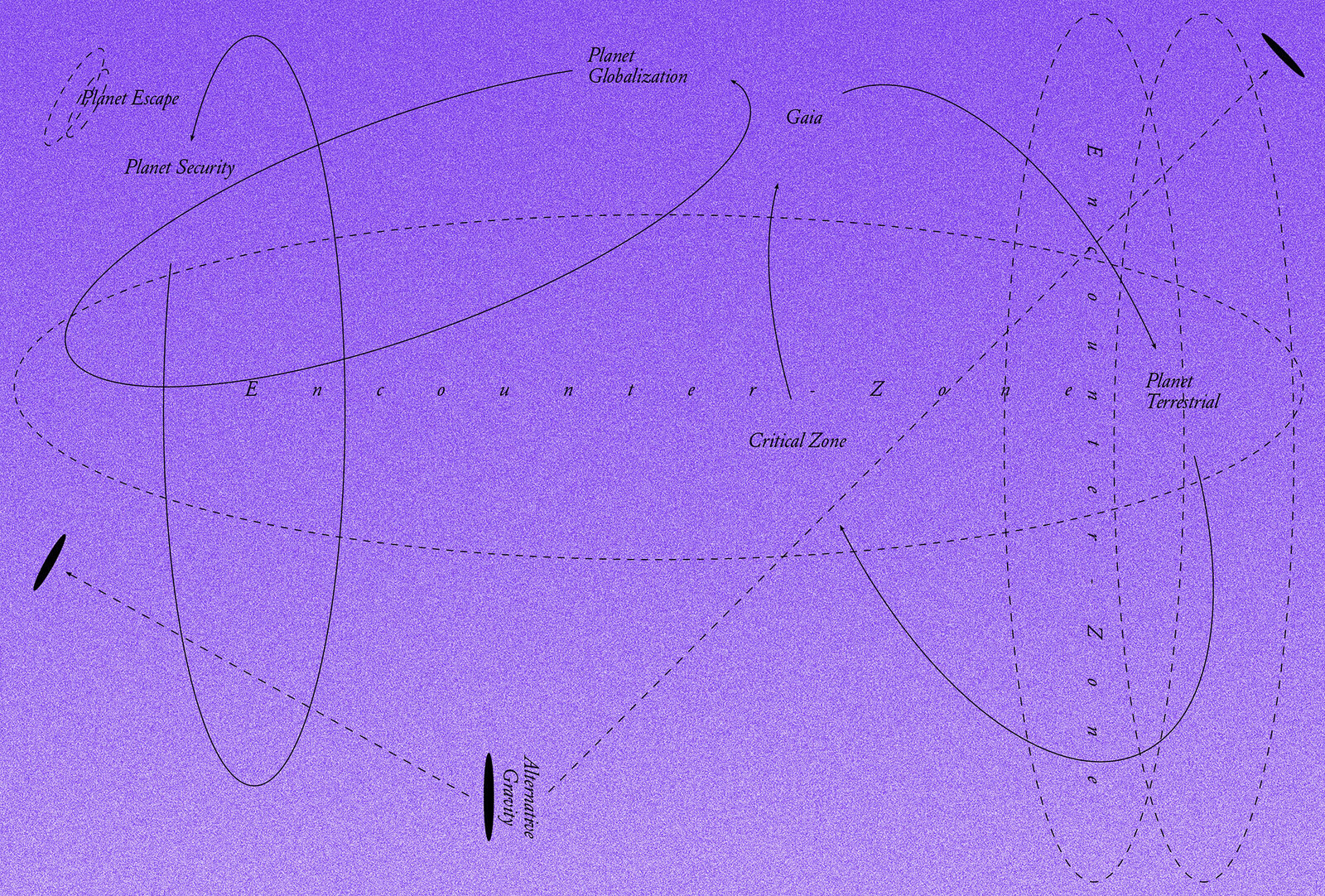

The hierarchy between temporality and spatiality established by the Axial Age and hyper-transcendentalized by the Christian eschatology infused in Western philosophies of history (Karl Löwith has always been right) is being empirically challenged by the extensive (imperial) and intensive (extractivist) closure of the earth’s frontier. So it is not surprising that the Anthropocene reenacts in scientifically up-to-date terms a “compact experience of the earth” (the local cosmos, the critical zone, the generalized symbiosis as the truth of Life), and that the latter requires a “spatial turn” of thought. With this, then, the primordial earth of the premodern and extra-axial peoples appears as an unexpected alternative within the planetary differendum proposed by Latour. The distinction between his planets Contemporaneity and Terrestrial37 is certainly a temporal difference, but it is a strangely circular temporality, as if he were saying: “The past is yet to come.” For the planet Contemporaneity is the autochthonous, ancestral, primordial earth that has always been there, that is, here; it is the “good enough planet” that political action must be able to reclaim from the “damaged planet” bequeathed to us by the previous planets.

We mentioned political action. The perspective suggested by Anders of the “apocalypse without kingdom” as the unthinkable of the Real—in contrast to the perverse unreality of capitalism’s “kingdom without apocalypse,” and the pious fiction of the “apocalypse with a kingdom” of Christianity and its utopian heirs—does not imply a quietist or fatalistic solution.38 The time of the end is the time of the “end of the world,” in the spatial, geographical sense that the Greek term eschaton also has39—it is the limit of the expansion of the capitalist cosmotechnical assemblage—and the end of time is, today, the growing degradation of ecological conditions, that is, of the conditions given in earthly space; an endless ending. The button of Anders’s total nuclear war has already been pushed, in the sense that the catastrophe is not yet to come, but already began many decades ago.

There is no more waiting, there is only space. Wouldn’t Paul Tillich’s kairós, Walter Benjamin’s Jetztzeit, designate the moment when “time becomes space”? When time is suspended, history exploded, and one enters space through action? The time when fighting for the earth means, first of all, joining the struggle of the landless peoples who were and still are invaded, decimated, and dispossessed by the earthless people, the “Humans” of Facing Gaia, the people of Transcendence—“nous autres,” we the Whites, as so many indigenous peoples of the Americas are wont to call, well, Us?

So let us finish with the words of the shaman, political leader, and spokesperson for the Yanomami Indians in Brazil, Davi Kopenawa: “What the Whites call the future, to us is a sky protected from the smoke of the xawara epidemic and tied tightly above us!”

Yuk Hui, “Cosmotechnics as Cosmopolitics,” e-flux journal, no. 86 (November 2017) →.

Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History (1949; Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953).

Jaspers, Origin and Goal of History, 1.

Jaspers, Origin and Goal of History, 52, 61.

Jaspers, Origin and Goal of History, 61.

Robert Bellah, “What is Axial about the Axial Age?” European Journal of Sociology 46, no. 1 (2005): 73.

Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry 30, no. 2 (2004): 231.

See the excellent critical review by John Boy and John Torpey, “Inventing the Axial Age: The Origins and Uses of a Historical Concept,” Theory and Society 42, no. 3 (2013): 241–59.

Bronislaw Szerszinsky, “From the Anthropocene Epoch to a New Axial Age: Using Theory-Fictions to Explore Geo-Spiritual Futures,” in Religion and the Anthropocene, ed. Celia Deane-Drummond, Sigurd Bergmann, and Markus Vogt (Cascade Books, 2017), 37.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 2 (2009): 197–222.

The idea of going back three thousand years in order to recover the subjective conditions of the Anthropocene predicament has some illustrious antecedents. Think of the Dialectic of Enlightenment, where the authors decide to go beyond the critique of social domination within capitalism to undertake a transhistorical critique of instrumental reason (Ulysses as the first bourgeois!). Not to mention Nietzsche and his archaeology of truth as value, the deconstruction of the Hellenic equivalent of the “Mosaic distinction” that Jan Assmann sees in Abrahamic monotheisms. See Assmann, The Price of Monotheism (Stanford University Press, 2013).

Benjamin Schwartz, “The Age of Transcendence,” Daedalus 104, no. 2 (1975): 3.

It should be noted, however, that the celebration of freedom as a diacritical attribute of the species, the mark of its ontological state of exception, is widely distributed across the political spectrum, including, for example, among contemporary thinkers of the “communist hypothesis.”

Quoted in Vítor Westhelle, Eschatology and Space: The Lost Dimension of Theology Past and Present (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), xiii. The time of “axial” cultures, it should be noted, is conceived according to a linear and future-oriented scheme (terrestrial or supra-terrestrial), while “pagan” spatiality would be associated with a primitive cyclical (therefore temporally lapsed) temporality. See the classical essay by Karl Löwith, Meaning in History (University of Chicago Press, 1949); and the highly original study by Westhelle.

On the concept of negligence, see Latour’s commentary on a passage by Michel Serres in Latour, Facing Gaia (Harvard University Press, 2017), 152.

Alan Strathern, Unearthly Powers: Religious and Political Change in World History (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Strathern, Unearthly Powers, 4.

Strathern, Unearthly Powers, 132.

Stephen Toulmin, Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity (University of Chicago Press, 1990).

Stephen Jay Gould, Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time (Harvard University Press, 1987).

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Harvard University Press, 1993).

In Unearthly Powers, Strathern observes that certain core values of immanentist religiosity—wealth, fertility, consumption, victory, worldly success, etc.—are also dominant in modern secularized society (37). Nevertheless, the scientific culture he assumes in his analysis is, under important epistemological aspects, precisely “non-secular” in that it refers to an idea of Nature that is the direct heir of Christian transcendentalist monotheism.

Levy Bryant, “A Logic of Multiplicities: Deleuze, Immanence, and Onticology,” Analecta Hermeneutica, no. 3 (2011): 1–2.

Latour, Facing Gaia, 177.

Latour, Facing Gaia, 178.

Toulmin, Cosmopolis.

As Gunther Anders observed in Le temps de la fin (1972; L’Herne, 2007), the disappointment that accompanied the inaugural gesture of modernity, namely the collapse of the geocentric image, “must have been unpleasant, but it was not fatal,” because it was compensated by a new anthropological dignity: the absolutization of history itself.

Jean-Baptiste Fressoz quoted in Latour, Facing Gaia, 20, 191.

Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, 30.

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, May 24, 2015, §224 →.

The theologies of prosperity, very popular and politically powerful today in Latin America (and elsewhere), are originally associated with US so-called televangelism. “The distinguishing characteristic of contemporary prosperity theology is the miraculous quality of the blessing; material welfare is not merely a … byproduct of virtuous living, but it is, ipso facto, God’s supernatural gift to the faithful, not unlike other gifts of the Spirit such as glossolalia or faith healing.” Virginia Garrard-Burnett, “Neopentecostalism and Prosperity Theology in Latin American: A Religion for Late Capitalist Society,” Iberoamericana: Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 42, no. 1–2 (2012): 23–24. As to the demand for material emancipation, Chakrabarty has said: “‘The principal reason,’ writes Hannes Bergthaller … ‘why all the curves of the “Great Acceleration” are still pointing relentlessly upwards … is the spread of middle-class consumption patterns around the world.’” This is “the historically inherited obligation to the masses.” Bruno Latour and Dipesh Chakrabarty, “Conflicts of Planetary Proportions—a Conversation,” in “Historical Thinking and the Human,” ed. Marek Tamm and Zoltán Boldizsár Simon, special issue, Journal of the Philosophy of History 14, no. 3 (2020): 31, 36.

Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, 2013, §223 →.

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, §119. Emphasis ours.

The expression “stifling immanence,” in the Portuguese translation of Laudato Si’, is rendered as “a suffocating confinement within immanence.” Confinement—what a concept!

Latour in Latour and Chakrabarty, “Conflicts of Planetary Proportions,” 4.

Latour and Chakrabarty, “Conflicts of Planetary Proportions,” 14. Our emphasis.

Latour and Chakrabarty, “Conflicts of Planetary Proportions,” 17.

Günther Anders, “Apocalypse without Kingdom,” trans. Hunter Bolin, e-flux journal, no. 97 (February 2019) →.

Westhelle, Eschatology and Space, 2012.