Alessandra Franetovich: I would like to start by asking you a question about first contact. You first encountered the theories of Russian cosmism while working on your project The Last Pictures. Your project investigates the processes, methods, and purposes that lie in the creation of images, as well as the imagery and maybe even mythology that emerged during the space race of the previous century—mainly during the Cold War period. Stretching back much further, however, the development of Russian cosmism began with philosopher Nikolai Fedorov at the end of the nineteenth century. Indeed, talking about cosmism today, as well as about space travel, necessitates connecting three different centuries.

The Last Pictures proposes a reflection on humankind’s decades-long experience of living in the era of the “technosphere,” when humans are surrounded by hundreds of satellites moving in Earth’s orbit. These satellites are mainly used for communication, for mapping Earth, and for military purposes. Some of these early satellites still function today, while others are just orbital garbage that we cannot, at least for the moment, recuperate or recycle. You envisioned a hypothetical future after the extinction of humankind in which the satellites remain. In such a future, these artificial objects become ruins of modernity and monuments of a past civilization. Following from this scenario, you conceived an artwork shaped as a disk that stores a huge amount of photographs and documents, which you then placed on a satellite. This work could be interpreted as a re-reading of the Voyager Golden Records that NASA sent into space in 1977. However, you followed quite different criteria than the space agency when selecting images to be included on the disk. For this artwork, you intertwined ethical and aesthetic dimensions. Russian cosmism is absolutely based on this duality, too. How did the theories of Russian cosmism inform your thoughts?

Trevor Paglen: I had actually started two projects, Orbital Reflector and The Last Pictures, at the same time. They were two very different approaches to thinking about how to work with space. During that period I was also working with Marko Peljhan, a Slovenian artist who teaches at UC Santa Barbara in California. He had been teaching some theories from Russian cosmism in his classes. These ideas were not very familiar to Americans, but Marko is well versed in those intellectual histories, given his much stronger connection to the Eastern European and Russian histories of space. One of the big things that I was struggling with while working on The Last Pictures is that, at least in the American mythology, space is an extension of the frontier. So, you go into outer space, you go to the moon, you plant a flag, you do some mining on asteroids, and the idea is that it’s Nevada again, or California again. I was trying to contradict that story, or that way of thinking about the cosmos. I wanted to tell a different one about space—not as a limit, and not as a horizon of possibility, so much as a limit and an encounter with the kind of something that is radically other. And that radically other thing could be space itself, or theories of infinity, and so on. When you get into things happening in solar systems and galaxies and the cosmos itself, you enter a form of time that is very alien to the ways in which we perceive and experience time as humans. So what does that encounter produce between a moment in human history and a moment in a human lifetime within the vast scales of time that characterize the universe? Marko introduced me to some of this thinking, and it made a lot of sense to me, especially because I read Fedorov in a much more allegorical way perhaps than I think he meant his work to be read. I read Fedorov by thinking about him as starting a tradition in which space flight is a series of encounters with something that is both radically other and radically one’s self. On the one hand, it means going into something that’s very different. On the other, that thing that is very different is also a deep reflection of something in you, or the culture that you come from, or what have you.

Trevor Paglen, SSO-A Launch, 2018. Copyright: Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the Artist and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco.

This was a useful way to think about a project like The Last Pictures, the premise of which was to put a collection of images into space, but more importantly, putting them into time—in a way that is radically different than the ways in which we normally insert images into time, or think about images in relationship to time. Questions then start to arise, like: What does an image mean, if anything? And what does meaning mean, if anything? All these strange reflections happen when we insert something from a human timescale, and from a specific moment in human history, and a specific set of situated ways of seeing and situated knowledge, and put it into a context that is much broader and universal. And, at the same time, there’s an understanding that those things don’t translate, and can never translate. So, what is it exactly that you are doing, then? For me, that was the central question of The Last Pictures. Cosmism provided a much more helpful way to think about those kinds of questions than a kind of Western, riding off into the sunset, cowboy version of space—or even a conception of space characterized by NASA and the people who worked on the Golden Record project, which was still very much the imagination of an encounter with an alien civilization or something similar.

AF: In 2018 you launched the artwork you just mentioned, Orbital Reflector, in collaboration with the Nevada Museum of Art, and put it into lower orbit using a Space X satellite. The work is a nonfunctional satellite that was intended to release a giant reflective balloon in the form of a diamond. This diamond-shaped balloon was supposed to move around the Earth to reflect lights, so that it would have been visible to the naked eye. Examples abound of artworks realized in response to the imagery of the cosmos, or from the observation of planets and stars done for religious, scientific, and also artistic purposes. We can think of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of the moon, or Vladimir Tatlin’s Letatlin (1932), which both seem to be interested in human flight. That is to say, those works follow from reflections about how to create communication with outer space—i.e., with another dimension. But what I think is particular about your work is the concept of the satellite as an art piece.1 How did you come to conceive this experiment? And is there something specific in selecting the diamond shape?

TP: For me, a lot of different threads fed into thinking about the spacecraft itself as a kind of sculpture. On one hand there is a question which has to do with the politics of space, with looking at the history of space flight, and then asking what kinds of objects humans have put into space. Historically, those kinds of objects fall into three categories: military satellites, communication satellites, and scientific satellites. And that’s it—that’s all of space flight. And I would go further to say that all commercial and scientific-based flight is subsumed under military space flight. Furthermore, I would argue that there’s no such thing as space flight without nuclear war. It was invented to facilitate nuclear war, not to facilitate space flight itself. When you think about that whole history, the actual practices of space flight are entirely militarized, 100 percent, through and through.

The political provocation that I was trying to ask was this: In relation to the history of space flight, can we imagine making a spacecraft whose political logic is the exact opposite of every other object that’s ever been put in space? One that has no military value, no scientific value, that is somewhat radically aesthetic, but whose aesthetic creation has very different kinds of politics built into it? That’s the imagination. Now, I actually don’t think that’s ever possible to achieve, but that is one of the animating ideas. And there are many contradictions within that, and that’s fine. There are always contradictions with things in the world.

A second set of ideas informing it are, again, influenced by cosmism in a way. And when I say cosmism, I really mean Fedorov, who is the person that I have read and feel like I understand within the broader traditions of that philosophical school. Part of Fedorov’s project is the imagination; in short, to imagine planetary-scale infrastructures that benefit everybody. He’s proposing a kind of true internationalism with infrastructures that would be detached from the kind of territories and political logics of nation states. He’s trying to imagine big cables that would encircle the world and be able to influence the weather—again, planetary-scale infrastructure ultimately designed in radically egalitarian ways. That vision of a different kind of infrastructure is another one of the inspirations that went into Orbital Reflector.

Related to that is a series of questions about territory, space, and public space, and how to define public art. Can we imagine other kinds of art that are public in ways that can be detached from territories, borders, nation states, and so on? These project come with high internal contradictions. And one can even say that the question is a kind of colonialist premise. I recognize that, but I’m just saying, we have to do something, we have to have different kinds of imaginings. And this was one of my attempts to imagine something else.

Third, the decision to have the object a reflector is also a very cosmist thing to do, perhaps. The Last Pictures was a reflector as well. They’re both cosmist in the sense that you create an object that can only ever be understood through the particularities of your moment in time, and through the particularities of the weight of what you bring to it. Space is a fantastic backdrop to be able to ask those kinds of questions, because we have no idea what space is like. Space is mostly just what we imagine it is. The idea of a reflector as an allegory makes that very explicit: the thing that we see is the reflection of the thing that we want to see.

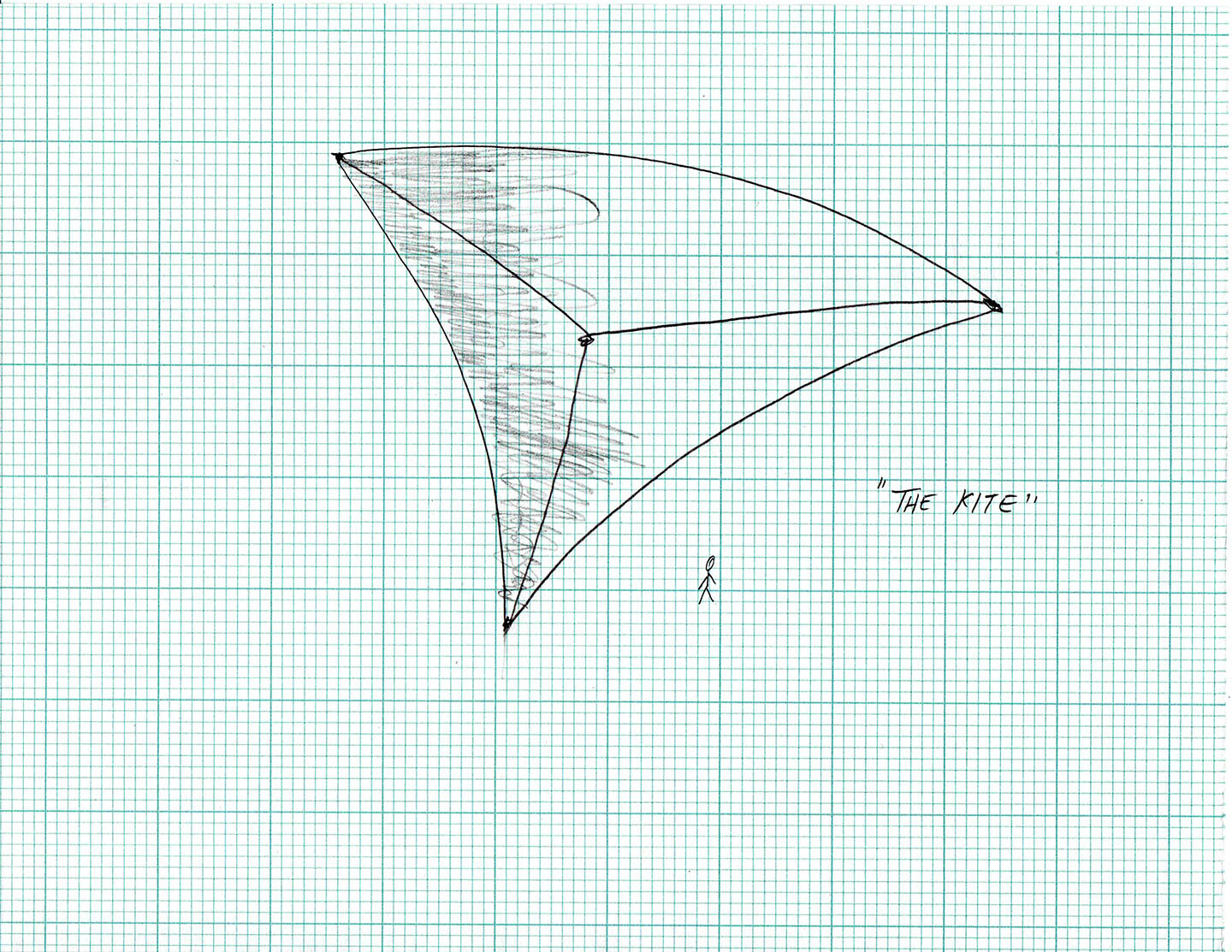

Finally, there were aesthetic as well as technical reasons for the diamond-shaped Orbital Reflector. The technical reasons are two-fold: on one hand, you’re trying to design an object that has the maximum amount of surface area that can reflect light. The most efficient shape possible to meet those criteria is a sphere. We’re actually not interested in surface area per se, but in reflective surface area, which is a different question. It turns out the most efficient shape for doing that is something much more cylindrical. For aesthetic reasons, I didn’t want it to be a cylinder, but it needed to be in the ballpark of cylindrical shapes for reflective reasons. The other reason has to do with aerodynamics. When you’re in a low Earth orbit or even a medium Earth orbit, a spacecraft experiences small amounts of atmospheric drag. But as you go further up into space, there isn’t a specific line that separates the Earth’s atmosphere from outer space—the atmosphere just gets thinner and thinner and thinner, to the point where, even hundreds of kilometers up in space, there are still particles of carbon dioxide and oxygen evaporating into space. When satellites hit those particles, it creates friction, and the satellites slow down and are eventually brought back to Earth. Satellites have to continually boost themselves into higher orbits to stay up. By creating more of a fuselage shape, you can minimize the effects of that atmospheric drag, and therefore allow your spacecraft to have a longer time in orbit. All of those things came together, so there were very serious technical restraints on the possible range of shapes that it could take. And within that possible range of shapes, I chose the diamond.

Trevor Paglen, Orbital Reflector, 2013. Archival Materials. Copyright: Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the Artist and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco.

AF: I would like to further investigate your reference to public art, because this is indeed another peculiar aspect of your artistic research. Hypothetically, The Last Pictures could be picked up by somebody in the future and decoded, while Orbital Reflector is even more radically public. To me, your interest in the concept of the “public” also resonates with the idea of the “common” that was at the core of Fedorov’s theoretical work, published posthumously in a volume titled “The Philosophy of the Common Task.” There is an interesting relation between this and what you said concerning the politics at play in our lives. The reality of national politics did influence your work in a very real way. When the US government shut down between 2018 and 2019, this unfortunately broke the connection with the satellite used for Orbital Reflector. This event might be interpreted as the intrusion of fate, which is a huge topic, especially in contemporary art. Did it change your own understanding of the artworks, or the entire project at large?

TP: That’s right. Despite trying to make this radically public artwork, you are still constrained by the fact that the work must be made within a nation state structure. Individual states regulate space launches, and so you can have a little bit of freedom in terms of how you pick what national system you want to be regulated by. But, regardless, you’re gonna be regulated. In the US, that regulation is done by a combination of the FCC (the Federal Communications Commission), the military, and NASA. When we launched the satellite, we were in communication with it. It was a small satellite initially—about the size of a shoebox. It was launched in a collection of other satellites, but because ours was then going to blow up to be a gigantic mirror, we needed to make sure that we were not going to hit somebody else’s satellite when we did that maneuver.

So we needed to track it and give it a little bit of time so that it would move out of the way of other satellites. We were tracking it and communicating with it. To make that final maneuver, we needed to get a sign off from all of those agencies. But in the meantime, the Trump administration closed down the government because they wanted Congress to fund a giant wall across the border between the US and Mexico. They basically held everybody hostage in order to get the money to build this wall. And so, the government was shut down for around six weeks. During that time, we still needed to get the permission to expand the mirror, but there was nobody to call. The people at all of the agencies we needed to speak with were furloughed. There was no official mechanism left to release the giant reflector. In a very real way, the fact is that Trump’s wishes to build a wall with Mexico killed the Orbital Reflector project, which is obviously ironic for many reasons. In a way, it proved the point of the project, or one of the points of the project, which was to think about the relationship between the public and territories and borders. For me, it was a perfectly legitimate resolution to the project. It wasn’t the one outcome I expected, nor the one that we had planned for, nor the one that we had engineered. But from a conceptual standpoint, I think it is a perfectly fine way to end the project.

AF: Do you ever consider replicating this project?

TP: For me, the project is finished. I have a backup satellite that we built. There is the material existence of the project, which has more to do with the conversations produced in the process of designing it, and in engaging with the imagination of it. This is really the point of many of these kinds of projects. And that part was very successful, in my opinion. So I’m not actually sure what additional value trying to have a second launch would bring to the table.

AF: Kazimir Malevich, a reference for your project, left behind a great deal of writing. One fragment from his writing comes to mind. In a 1919 essay reflecting on Suprematism and its philosophical system, which is based on the use of colors and shapes, he ended the text with: “the white, free depths, eternity, is before you.”2 He noted himself that the final quest for eternity was a central subject of his research. I read this as a poetic statement that can of course be connected in various pragmatic ways to his work. Are infinity and its poetic drive also a reference point for you?

TP: For me it’s not these transcendental questions of infinity or form, and more about finding a way of translating those into practical questions, which are quite different things. And I’m not even sure that I’m going to be able to articulate what I mean by that. What was most influential to me was that he writes quite explicitly about wanting to build artworks that would go in orbit around the world. I think that in the introduction to his book Suprematism: 34 drawings publication, he proposes artistic constructions that would be put be in space and go around the world.3 And in a way he’s talking about satellites, but he was imagining that satellites would be artworks rather than military targeting machines.

Secondly, I think you can see that image in a lot of his drawings. I didn’t understand that when I was younger and learning about Malevich. Sometimes I do an exercise for which I imagine there’s no such thing as abstract art whatsoever, that all art is photo realistic. Then, if you look at Malevich and say, this is photo realistic art, you start to see cosmological things going on: planetary infrastructures and planetary aesthetics. And maybe that’s what I mean by translating the infinite into something that is—or what we imagine to be,—the transcendence of the infinite, and instead turn that into something like the photo-realistic infinite. What is the infinite that is not an abstract concept, but is in fact a realist concept? I guess for me that is much more obvious in a project like The Last Pictures, which is like entering a kind of time that is infinite for all practical purposes. But at the same time, the encounter with the infinite is made out of stuff, and was made out of images that do have very specific contexts, and come from very specific places. And so, what is it when those two things meet each other? Something that is extremely and specifically historical meeting something that is specifically ahistorical—when those contradictions come together, what does that allow us to see, if anything?

AF: Malevich wrote that text in 1920, and he named these structures, i.e. the satellites, “Sputnik.” Some scholars contend that the word was a neologism he invented. Today, exactly one century later, the term has become common in global discussions again—this time, however, it has to do with the possible discovery of a vaccine for Covid-19. Some weeks ago, a vaccine named Sputnik was registered by Russia, publically revealed by Vladimir Putin. Of course, this clearly demonstrates the fact that science is an instrument governments can use for propaganda, especially during “states of emergency.” Similar examples—of using the prospect of a vaccine as electoral propaganda—were obvious in the US during the presidential election, and elsewhere as well. What’s striking about the Russian example is that the government is invoking the glorious event of humanity’s first flight into outer space with the gravity of the current crisis. And it is also remarkable to note that such a famous name may have its origins in Malevich. It looks like art has the power to follow surreptitious means to come back into the eye of history.

This leads us to the notion of the historical convergence, or even equivalence of both art and science in constructing a vision of the surrounding world, or even for imagining provisional futures. This notion of the similarity between art and science is very present in Fedorov’s writings, for example. What is your opinion about the possible relation between them? Do you see something like a harmonic relation, or maybe stronger contradictions?

TP: Today, people tend to think about science as a way of looking at things, of experimenting with materials, for trying to understand outcomes or to develop ways of seeing that allow us to interpret the world in different ways. I see lots of similarities between that and art, and historically these things have at times been indistinguishable from one another. What troubles me about the reality of art and science in the (kind of) postwar era is that science has been intimately and inseparably connected to institutions of power, whether those are corporations, militaries, or industries of science. I see and am wary of what science gets out of the collaboration between art and science. I’m not so sure what art gets out of the deal.

Having said that, both The Last Pictures and Orbital Reflector were only possible because very skilled scientists worked on them. What was fun about both of those projects is that neither should not have happened. A big part of the project, in other words, is the creation of communities of people that can put different skillsets together in order to make the impossible happen. For example, while building The Last Pictures I often encountered a technical or engineering problem that I had no idea how to solve, and it needed be solved in three or four days, and it was Christmas, and there was no budget. I would get on the phone and call every single person I could find in the world that could solve this problem, explain it to them, and explain the constraints. Repeatedly, I found people that were excited and offered to help.

I went into engineering and science because I thought those fields were asking these kinds of big questions. But, they’re not. And so, in the process of asking these more poetic or imaginative questions, I found out that a lot of people in the sciences were originally animated by very similar kinds of problems. That was true of The Last Pictures and Orbital Reflector: both projects tried to locate questions that I think many get excited about, but that are not actually addressed in the fields that could try to answer them.

AF: Let’s develop your concepts of visibility and invisibility in relation to infrastructures further. Most infrastructural system are invisible to the naked eye—like the cables beneath the ocean or, again, satellites. Human society tends to hide the functional elements of our everyday technology from public view. To call this the era of the “technosphere” may seem like a contradiction, but it still allows us to speculate that humankind has leaned far into the radical distinction between “humanity” and “their own world.” In the 1960s (into the 1980s), the philosopher Günther Anders theorized about the “man without world,” by which he meant humans who become outdated by technology, and have therefore lost control of their relation to the environment. Our contemporary time is distinguished by hyper-specialization and the dissection of our existence and experience. Given this reality, we can see the detriments that come with harmonic or maybe even holistic connections with the environment, as well as the benefits imagined by those like the cosmists, by Fedorov, who was writing well over a century ago, and we are living in a completely different society. Where would you see yourself in this dichotomy?

TP: There are two contradictions that you’re talking about in terms of relating back to Fedorov: one is the contradiction between nature and culture, for lack of a better phrase: between the humans and things that are not the humans, as well as the conceptualization of those as different things, which is certainly evident in Fedorov’s work. Then the second contradiction is what we might call the alienation between people and technology. As technology’s become systems that undergird a lot of political systems, cultural systems, we find ourselves enmeshed within those to the extent that we end up being influenced in ways that we don’t entirely understand. Something like a YouTube algorithm would be a very simple explanation of that, in terms of propagating ideas across culture and influencing generations of people in ways they don’t necessarily perceive.

One more complicated scenario to analyze would be nuclear weapons: How do infrastructures required for nuclear weapons create political institutions and create possibilities while foreclosing others? On a very broad philosophical level, my instinct would be to not worry that much, precisely because the idea that every person could understand every system that they engage with is already almost a bourgeois conception of the individual. Because no one person can ever understand everything. I think if you take a different kind of Fedorovian approach, you can say, well, are there ways in which we can collectivize knowledge which we don’t have to be alienated from? That’s a different system, but maybe the scale of the individual versus technology is not the most useful scope within which to think about these contradictions. Having said that, throughout Fedorov’s work, as well as Marx’s, there is a kind of transcendental communism. That’s the way I like to read it. I actually don’t think that it’s necessarily meant to be there. It’s way more religious and weird, which we don’t talk about that much with Fedorov. Fedorov was not a great guy as far as I’m concerned. Some of the ideas are fun to play with, and some of them are really not.

But the point is that I think one can imagine a society in which there can exist large technological infrastructures that don’t have to extract value from individual humans or be turned against society. They don’t have to be turned against people. Now, within a capitalist economy, they are going to inevitably work against people and workers who are sites for extracting value. But I think that in the imagination of Fedorov, or in the imagination of Marx or Lenin, you could imagine infrastructures and technological systems at large scales that are not alienating. Again, we’re talking about imaginative structures, which for me is one of the fun things about the cosmos.

Trevor Paglen, An Unseen Star (OR-1 Search in Cepheus) Delamar Dry Lake, NV, 2019. Dye sublimation print, 48 × 60 in. Copyright: Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the Artist and Nevada Museum of Art, Reno.

AF: You’re trying to imagine a kind of egalitarian future society, or at least more egalitarian than today. While we wait for the realization of this fantastic and ideal society: Do you think that in order to achieve better living conditions, it would be enough to be aware of these various systems of manipulating or engineering reality—which of course can be employed for both positive and negative ends? Or, do you imagine other effective means? For me this then raises the question of how you perceive the role of art today.

TP: In a project like Orbital Reflector—as well The Last Pictures to a large extent—the strategy is to make objects that are kind of radically nonsensical. That are just really weird. Like why did you do that in order to point out the fact that we could say the same thing about infrastructures that we take for granted? And we can look at a project like Orbital Reflector and say, why did you do that? Well, we could ask the same question of nuclear weapons. We could ask the same thing about rockets in the first place. We could say: that was a terrible idea, why did you do that? And I’m not saying Orbital Reflector was a terrible idea, but the rhetorical or artistic strategy was to make objects whose logic tries to contradict the system that they emerged from. For a while, I called them impossible objects. One impossible object is a spacecraft that doesn’t do anything and doesn’t make money for anybody. It is just meant to be an aesthetic object, and it’s created by working within the existing space industry. That is not the kind of object that would emerge organically from the existing industry. Though, “organically” is a tricky word. But, all the same, it’s not something that the logic of the system would tend to produce. I also think about the works as opposite objects somewhat. In a way, The Last Pictures was about imagining what it would mean to try to take responsibility for the long-term footprint that humans have on the planet. How to have an ethical relationship with the deep changes to the planet for which humans are responsible? And even using a word like “ethical” doesn’t really apply, because the timescales are too different. Again, there is a contradiction between the ways we can think and what we can do, which are on radically different timescales. But the point is that both projects were designed to do precisely what the industries that made them possible would not do. That’s the strategy.

I can think of only one other historical example of this in the work of Yuri Leiderman. See my “Cosmic Thoughts: The Paradigm of Space in Moscow Conceptualism,” e-flux journal no. 99 (April 2019) →.

Kazimir Malevich, “Suprematism”, in Tenth State Exhibition: Objectless Creation and Suprematism, 1919; reprinted in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902–1934, ed. and trans. John E. Bowlt (Thames and Hudson, 1998), 145.

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematizm: 34 risunka (Suprematism: 34 Drawings), (Vitebsk: UNOVIS, 1920).