Was it only last Thursday that those of us in the Americas awoke to the bewildering news of David Graeber’s (1961–2020) passing? Whenever a person at the height of their capacities dies, there is shock. But among David’s extraordinary circle of friends, the confusion is absolute. How can a person who embodied the possibility of another world, who truly lived as if he was already free, not be here? Was it the sheer force of that astonishing intellect? Did it burn so very brightly that it could not be sustained? How can it be that David, who cared so deeply about the radical possibilities of the imagination, endured a death in Venice during this pandemic, as if critiquing even at the last?

Yet this is the media age, and all has already been wrapped and disposed. His anarchist publishers posted David’s own biographical statement.1 In a flurry of hours, the initial Twitter storm gave way to the obituaries from the liberal publications like the New York Times, which never had much time for him in life. Even The Guardian, which David detested so much for its role in creating the moral panic over “antisemitism” alleged to have run rampant in the UK Labour Party that his Twitter account still has a pinned tweet quantifying the false statements they printed,2 quickly ran a long remembrance.

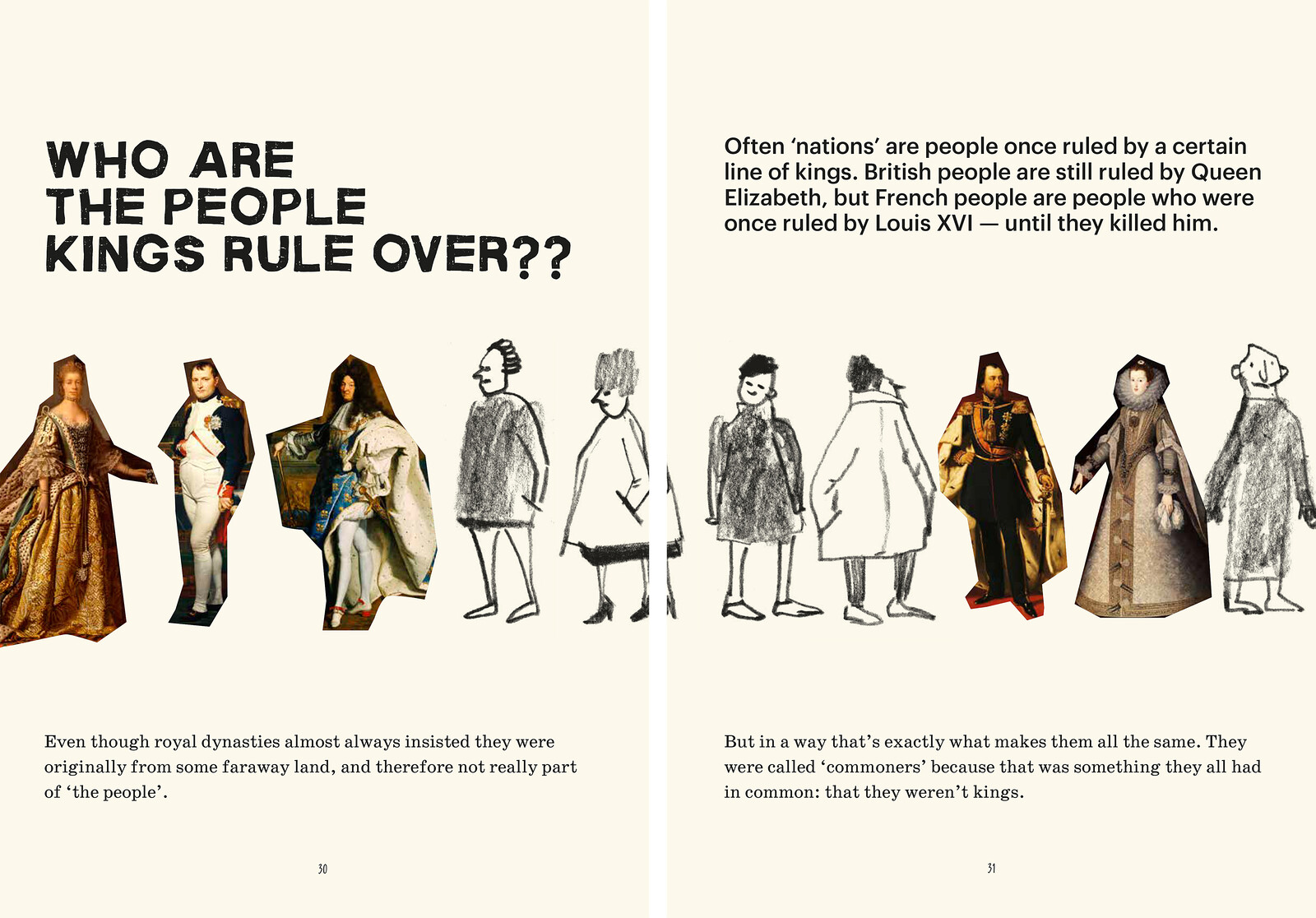

But David’s work isn’t even all published yet—his next book with David Wengrow is called The Dawn of Everything, a very David title. Here was what academics keep saying they wanted: a scholar engaged with the widest questions there are to ask, completely connected to the world as it is, and as it should be. People carried Debt: The First 5000 Years in the streets during Occupy Wall Street and read it together page by page in seminars David organized. Yet Graeber was driven out of US academia, by underhanded means, into what he called “exile” in London. It is a bitter irony that he had recently established both professional and personal happiness in the UK, above all with his beloved wife, the artist Nika Dubrovsky. Among their many ongoing projects was a fabulous series of illustrated books for kids on conceptual issues like anthropology.

The untimely dead leave behind them a gift, one that the living may not want. That gift is the perception of the shape of the space that we have imposed on the departed, above and beyond the space that they actively chose for themselves. Did we not ask too much of David Graeber? Perhaps so, and there will be time to consider and to mourn. Before that time comes, each of us that found energy in all that David did and thought, from his direct actions to his exposure of debt and the identification of bullshit jobs, will have to look at that space and decide, individually and collectively, how it is to be filled.

Here again, it will be possible to learn from David Graeber. In his decades of activism, he persistently refused to do “leadership.” Not that he didn’t intervene, or give advice, or mentor people, because he did all of that and much more. Because he tried to live an everyday communism every day, he would not impose any direction, even if he would sometimes express frustration outside movement spaces as to what was happening. A movement was just that: a moment and course in time and space. If and when it fails, you go on to the next one. As all of his writing insisted, the utopia of unchanging rule is that of religious or political domination, not one of freedom. There are ways to learn, and ways to help others learn, in there.

During Occupy Wall Street, the refusing words of Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” became a slogan: “I would prefer not to.” The phrase appeared on signs and stickers around New York City. It was a fold in the times of resistance, where pasts that are not fully past become present and available; the unexpunged energy of past refusals to move along or to pretend there was nothing to see became active again. This is what we mean when we say David is now with the ancestors: that his immense archive of words and ways of being, laughing, and being with others have become a permanent resource to draw upon when needed, especially in the dark times that are upon us now.

It’s not Melville or Thomas Mann that I turn to now in measuring the loss, in preparing for the dark times, in making do the undoable. It’s the words of the Irish exile and French Resistance supporter Samuel Beckett in closing The Unnamable (1953): “Perhaps it’s done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” I’ll leave you here. Go on.