“Can truth be mortal, falsehood live for ever?” – “I think that’s clear.”

“Where have you seen long-overlooked injustice?” – “Here.”

“Who knows a man whose violence made his fortune?” – “All of us do.”

“Who then in such a world could rout the oppressor?” – “You.”

—Bertolt Brecht, “Questions and Answers”I considered it a necessity to work with people who, just like me, saw the revolutionary movement as the driving force, the engine of their creation. To me, the whole idea behind the proletarian theater revolved around the building of a community that would be human and artistic, but also political.

—Erwin Piscator, The Political Theater

Prologue: The Porous Generation of the Avant-Garde

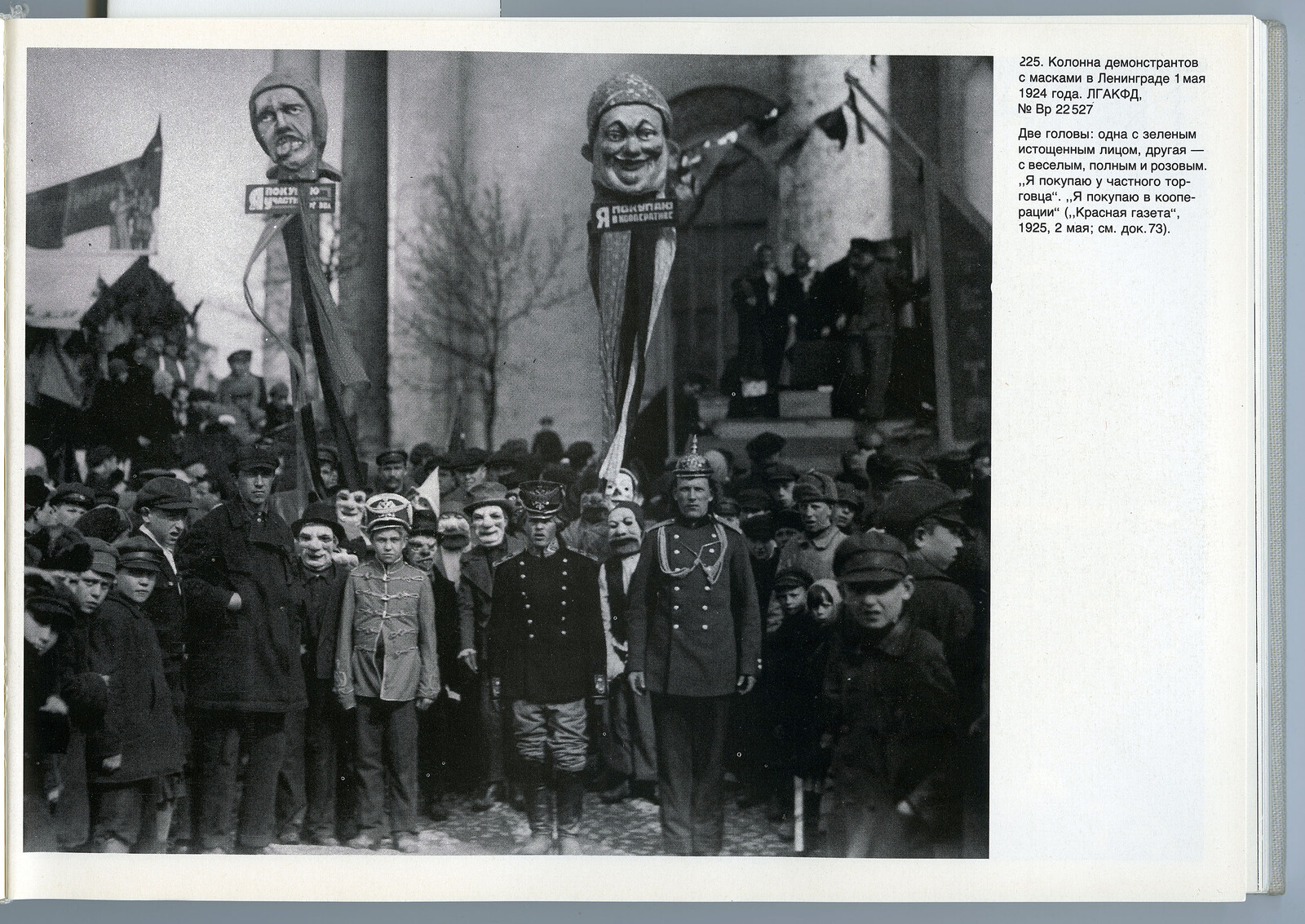

The “turmoiled” beginning of the twentieth century in Europe and Russia—with Western modernity and capitalism irrevocably heading towards their “cul-de-sac” of subsequent economic crises, attempts to overthrow regimes and governments, recessions and repressions, as well as the First World War and the October Revolution—became a “cradle” of a whole new transnational generation of artists and intellectuals. This generation reached their maturity and became aware of their aspirations and working methodologies through disillusionment, crises, and frustration, gaining a voice that they made heard during the Golden Twenties and early 1930s in geographically different contexts, maintaining certain inter-contamination between their distinct traits. Notwithstanding the obvious cultural and political disparities, members of this new generation, as Susan Buck-Morss put it,

experienced “the fashions of the most recent past as the most thorough anti-aphrodisiac that can be imagined.” But precisely this was what made them “politically vital,” so that “the confrontation with the fashions of the past generation is an affair of much greater meaning than has been supposed.”1

These sometimes irreconcilable avant-garde groupings became radicalized through a shared traumatic experience which taught them “that the phantasmagoria of progress had been a staged spectacle and not reality.”2 Politically disillusioned and misrepresented, these orphans of failed modernist aspirations were thirsty to fuse art, life, and politics in order to shatter the old bourgeois ways and forms of life once and for all in favor of something yet to come, a new world they strove to erect on the ruins of the preceding one. As Jean-Michel Palmier states in his “Weimar in Exile,”

Communists, Socialists, pacifists, republicans, liberals and non-partisan writers, these intellectuals embodied throughout the 1920s an aspiration towards liberty, a critical and moral conscience that was almost unique … They were also perhaps the last generation of intellectuals to believe in the power of the word over history.3

The time-space coordinates of the territory of their interventions spanned from Weimar Germany to the newfound Soviet state in Russia, covering the entirety of Europe along the way. As Leon Trotsky wrote in his My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (recalling the year 1908),

For us Russians, the German Social Democracy was mother, teacher and living example. We idealized it from a distance … in spite of my disturbing theoretical premonitions about the German Social Democracy, already mentioned, at that period I was undeniably under its spell.4

The same can be said about the new generations of German and European intellectuals, who, from the 1920s onwards, fell completely under the spell of the October Revolution in Russia and its cultural protagonists and advocates.

The so-called “Russian Berlin” was a vivid reality until the mid-twenties, similar to how Moscow was home to German, Latvian, and other émigré diasporas with their magazines, theaters, and publishing houses until the late 1930s. Cultural exchange was booming. The great impact that the October Revolution, as the first model of a socialist revolution, had on intellectuals in Europe (and in particular those in Germany) was a fact which Stalinist politics speculated on extensively. The Revolution’s universal prestige started to bend only towards the end of the 1930s, coinciding with the Moscow trials and the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact (1939):

Kameny Theater, Vakhtangov Theater, Blue Blouse, and the Meyerhold troupe exemplify the relatively free passage of dramatic art from Russia to the West. Among the willing emissaries were Anna Lācis, Bernhard Reich, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Sergei Tretyakov, and Sergei Eisenstein. German artists and intellectuals (such as Brecht, Piscator, Toller, Becher, Huppert, and Benjamin) in their turn travelled to the Soviet Union in order to experience for themselves the tenor of art and life in what was heralded as a new and more humane society.5

If initially the lines of advocates of “left-wing culture” and “cultural Bolshevism,” for whom art “was the most powerful weapon for Organizing collective forces,”6 were fit, only a few of them followed this One-Way Street till the end, without taking side turns.

The traces of this generation remain disturbing to any dominant order, sometimes even to their former peers and friends. Their true agendas, aspirations, and dreams, however silenced or put on hold, continue resurfacing amidst historical readjustments. Their most intimate convictions were never fully bent, not even by the most sadistic of repressions inflicted on them. A unique invisible thread links the disparate trajectories of intervention of these last protagonists on the shared stage of the short century.

So, how can we navigate through such a complex historical archipelago without breaking on its network of underwater rocks? In his Berlin Chronicle, Walter Benjamin proposes drawing a diagram or a “psychogeographic” map:

I was struck by the idea of drawing a diagram of my life … I have never since been able to restore it as it arose before me then, resembling a series of family trees. Now, however, reconstructing its outline in thought without directly reproducing it, I would instead speak of a labyrinth … It was on this very afternoon that my biographical relationships to people, my friendships and comradeships, my passions and love affairs, were revealed to me in their most vivid and hidden intertwinings.7

Let us apply a similar method to outline the contours of a constellation of one such radical avant-garde grouping, by following the traces of its central female emissary, Asja Lācis. Her pedagogical, theater, and theoretical work, however misrecognized and subjugated, together with an account of her life and the vivid intellectual cross-pollination she was able to set in motion, remains one of the most fascinating forgotten pages of cultural history of the twentieth century. By no surprise, it echoed strongly with the anti-authoritarian aspirations of the post-1968 generation, and to the present day its emancipating potential has not dispersed its charge.

Given her centrality to this history, why do we know so little about Asja Lācis? Why has her name emerged mainly through the already fully assimilated histories of her male colleagues? How and when did such a deliberate marginalization, trivialization, and patriarchal disqualification of Lācis occur? And what could be the routes or methodologies for redistributing the respect, authority, and representability she deserves and for reassessing her role on the stage of early twentieth-century history from a new perspective? Benjamin’s notion of a dialectical image and the Brechtian method of epic theater are both of great importance and will be used here as methodological references.

The following fractured and semi-theatrical montage will attempt to restage the complex story of Asja Lācis and a group of figures linked to her. The staging will be narrated in eleven interconnected acts, without any pretense of arriving at an exhaustive synthesis. On the contrary, through its freeze-frames, gaps, and asynchronies, a new type of interpretation that is strongly intertwined with the present situation may come to the fore. Hopefully it will equally shed light on the potentialities that still dwell dormant in her work and deserve to be rediscovered.

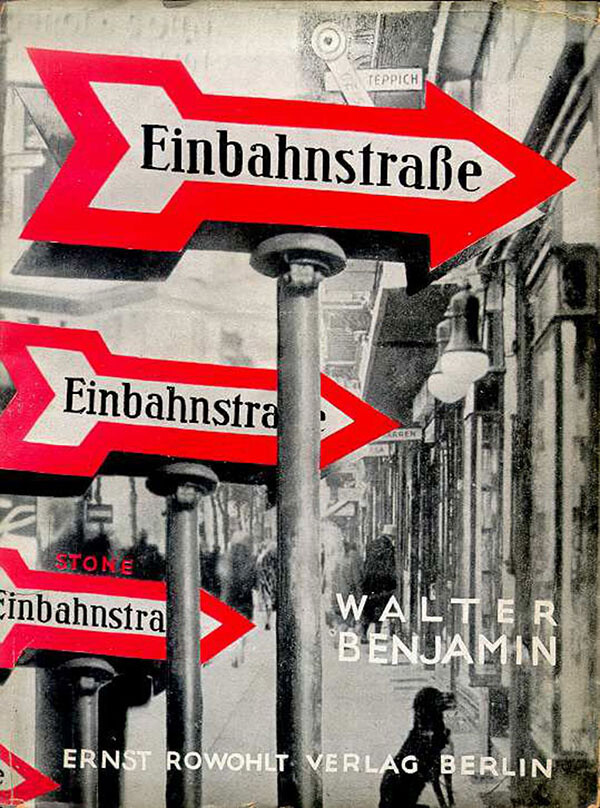

A cover of Walter Benjamin’s book One Way Street featuring a photomontage by Sasha Stone.

Scene 1: Asja, Engineer of the Avant-Garde

One-Way Street (Einbahnstraße), a collection of essays by Walter Benjamin (his literary montage in line with constructivist ideas), reached bookshops in Berlin in 1928. Its title was a radical declaration of intent and its opening page contained a cryptic dedication: “This street is named Asja Lācis Street, after her who as an engineer cut it through the author.”8

The “engineer” in question was Anna Lāce (born Liepiņa, 1891–1979)—internationally known as Asja Lācis—a Latvian theater director, actress, and revolutionary theorist. Not only this—she was also a playwright, pedagogue, and a feminist ante litteram who went on to become the protagonist, the intermediary, and the trait d’union between the German, Latvian, and Russian avant-garde cultures.

Following the labyrinthine topography of her life, a map emerges that leads to virtually all the early twentieth-century focal points of cultural innovation in Europe: from Riga to Berlin, Munich, Naples, Rome, Vienna, Paris, St. Petersburg, Moscow, and returning back to Riga. Departing from her early Soviet theater experience and the highly influential proletarian children’s theater experiment, at each of these topographical locations Asja Lācis set forth collaborations with leading intellectual figures, frequently creating a fertile ground for the emergence of unique “constellations.” It was through her that “the meeting of the greatest living German poet” with the “most important critic of the time,” as Hannah Arendt later described the encounter between Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht, became possible.9 She later contributed to the promotion of films by Sergey Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, among others in Germany (via Siegfried Kracauer); introduced the Soviet and Latvian public to the traditions of the German epic and the proletarian theater; and collaborated with Erwin Piscator and John Heartfield on the set of the film Revolt of the Fishermen (Восстание рыбаков). Last but not least, she created an original personal synthesis of political theater exercised in Russia and Latvia. Her affiliations with RABIS (Trade Union of Art Workers—РАБИС, Союз работников искусств), early RAPP (Russian Proletarian Writers’ Association—(РАПП, Российская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей) circles, and the newfound and more important Proletarian Theater group (Пролетарский театр) that emerged due to disagreements with RAPP leaders; involvement in the organization of the First International Olympiad of Non-Professional Revolutionary Theatres in Moscow in 1933 with the participation of agit-prop and workers’ theatre groups from more than sixteen countries, participation in the foundation of MORT (International Union of the Revolutionary Theater—МОРТ, Международное объединение революционных театров), collaboration with VOKS (All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries—Всесоюзное общество культурной связи с заграницей), and other groupings with international members and aspirations may help to further reveal the actual scope of a whole parallel underground network of the avant-garde that involved major left-leaning cultural figures on all latitudes (from Europe to the US and Japan), in which Asja played an important and yet completely underestimated role. These aspects of her activity still require their adequate historical evaluation. The same applies to her theater work, her anti-authoritarian and antifascist educational work, and her writing, all of which will hopefully attract more international attention.

Scene 2: Theatrical October

Lācis completed her early education in Riga, where her working-class provenance begat many unpleasant confrontations with the bourgeois realities of the period. Her true loves since childhood were literature and theater. She absorbed works by Ibsen, Maeterlinck, Russian decadents, and French and Latvian symbolists.

Her real ideological and artistic formation occurred in St. Petersburg and Moscow. From 1912 til 1914 she took courses at the Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute, in 1915 she enrolled as a student at the Moscow Shanavsky’s Cultural University, and then pursued studies at the Fyodor Komissarzhevsky Studio from 1916–1918. Bekhterev’s new institute in Petersburg was one of the most innovative and unorthodox educational institutions of its time, open to women and students from various diasporas (most institutes had limited quotas of admission in the best case). Courses spanned from psychology to philosophy (especially Nietzsche) and law, and professors always encouraged students to form, express, and argue their opinion through experimental formats including literary trials and philosophical disputes. Asja absorbed the cultural richness of Petersburg and later Moscow by actively participating in its academic and cultural life, visiting opera, theater, exhibitions, witnessing plays by Vsevolod Meyerhold, Nikolai Evreinov (his theatrical mass reenactments like Storming of the Winter Palace), Alexander Tairov, Konstantin Stanislavsky, and poetry readings by the young Vladimir Mayakovsky.10

Komissarzhevsky Studio in Moscow provided an equally nonclassical approach to theater education. As Asja recalls: “Fyodor Komissarzhevsky was convinced that there is no art without philosophy. The actor must first study philosophy and form a scientific worldview … I agreed with him that art must be taken seriously, that it can only be created by people with a certain worldview.”11

The International Olympiad of the Revolutionary Non-Professional Theatres Bulletin, No. 5, 1933, Moscow published by MORT. International Union of the Revolutionary Theater. Collection of the author.

This intellectual training, along with being witness to the revolutionary events of 1917 and affiliated with a core group of avant-garde artists, poets, theoreticians, and film and theater directors—among them Vladimir Bill-Belotserkovsky, Evreinov, Eisenstein, Mayakovsky, Meyerhold, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Tairov, Sergei Tretyakov, and Vertov, among others—became the cornerstones of her future engaged practice. Asja writes:

When I read the first proclamations addressed “To the People, To the People!” signed by Lenin and posted on the walls, I was completely for the Communists. I wanted to be a good soldier of the revolution and to change my life in line with it. And all around me, I saw life changing: the theater moved out onto the street, and the street moved into the theater. The “Theatrical October” burst forth.12

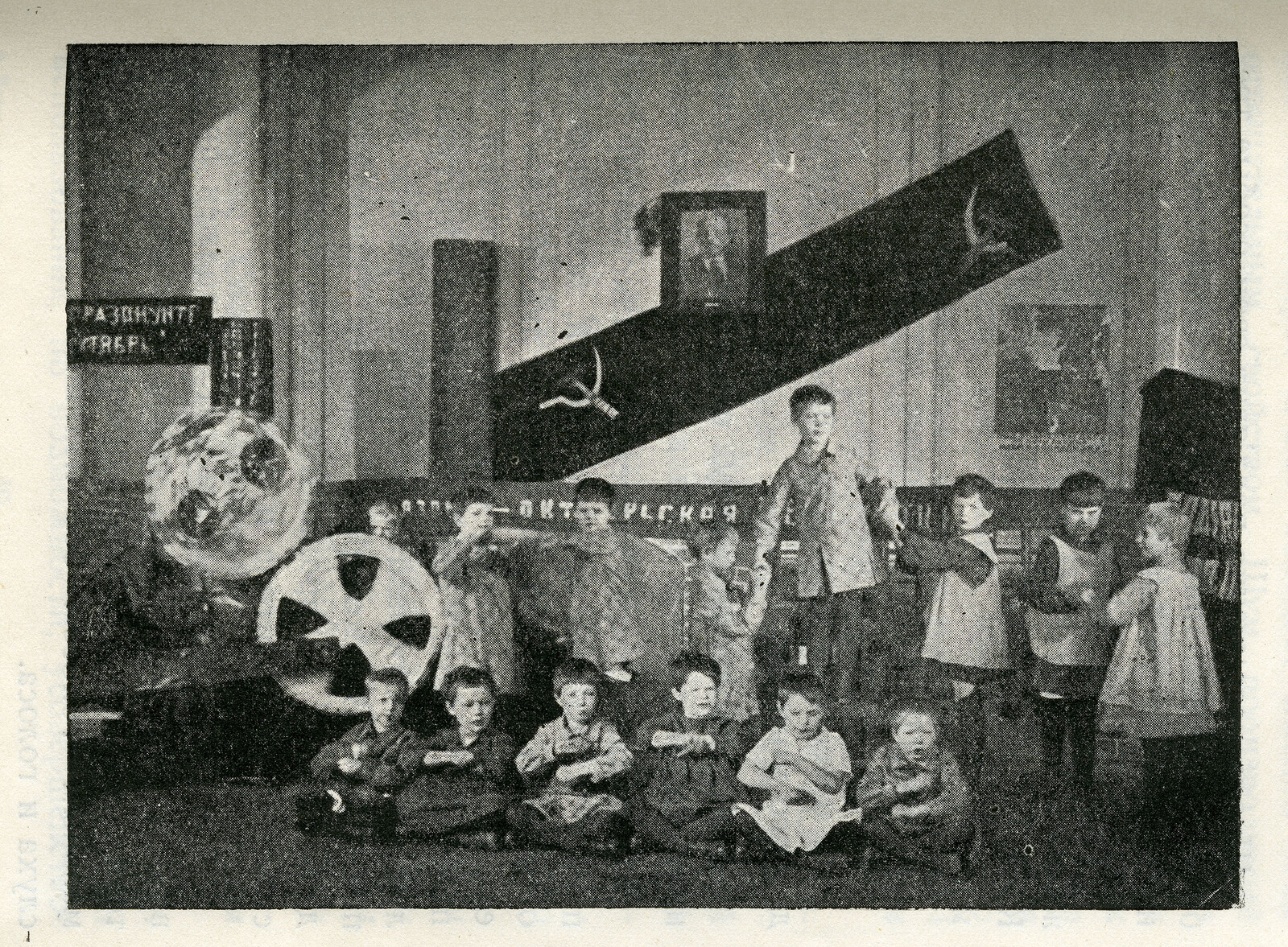

Scene 3: The Orel Experiment: Theater as a Site of Proletarian Education

In 1918, the Russian village of Orel became a stage for Lācis’s important experience with besprisorniki, as Russian war orphans were then called. Her experimental children’s theater helped local children overcome the trauma and violence of the postwar period through improvisation, performance, and play. It was a children’s theater made by and for children. The theater emphasized process rather than result, a praxis where participative and collective dimensions became more important than the final spectacle. This empowering venture laid the basis for Lācis’s methodology, which she would later apply to her proletarian and political theater work:

In 1918, I went to Orel. I was supposed to work as a director in the municipal theater—in other words, to follow the traditional theatrical path and make my career. However, things turned out differently. On the streets of Orel, at the market places and cemeteries, in cellars and destroyed buildings, I saw gangs of abandoned children: the Besprisorniki … They looked at you like old people, with sad, tired eyes. Nothing interested them. Children without a childhood … You couldn’t remain indifferent when confronted with all of this. I felt I had to do something, and I knew that children’s songs and nursery rhymes would not be enough here. In order to get them to break out of their lethargy, a task was needed which would completely take hold of them and set their traumatized abilities free. I knew how great the power of making theater was and what it might do for these children.13

The theoretical synthesis of her experiment with children’s theater in Orel was later provided by Benjamin, who in 1928 came up with the well-known “Program for a Proletarian Children’s Theater,” based on her experience—a fact later forgotten (or deliberately omitted):

Proletarian education needs first and foremost a framework, an objective space within which education can be located. The bourgeoisie, in contrast, requires an idea toward which education leads … The education of a child requires that its entire life be engaged. Proletarian education requires that the child be educated within a clearly defined space. This is the positive dialectic of the problem. It is only in the theater that the whole of life can appear as a defined space, framed in all its plenitude; and this is why proletarian children’s theater is the dialectical site of education.14

With this early experience mediated via the program written by Benjamin, Asja actually laid the groundwork for those experimental drama practices that later emerged under the labels of political children’s theater, amateur dramatics, theater-in-education, community theater, and animazione teatrale, i.e., drama/theater as a process of an anti-authoritarian aesthetic education with a strong bent towards social empowerment. This was a practice that emphasized theater as a tool for the acquisition of critical consciousness, with an emphasis on reactivating and liberating creative and bodily expression, energy, blocked gestures, and vital impulses via collective work within a circumscribed setting: “community.”

Scene 4: Persecuted Theater

From the moment of her unconditional adhesion to the Soviet revolution, the stages of her existence—as the theater critic Eugenia Casini-Ropa underlines—are identified with those of the proletarian theater, reflecting the tensions and the conquests, the aesthetic-theatrical and the social and political implications, of the revolution.

Upon her return to Riga in 1921, a young and energetic Lācis published her programmatic text “New Tendencies in Theater” in the magazine of the second Leftist Trade Union Culutural Festival (Kreiso Arodbiedrību Kultūras Svētku biļetens):

As a revolutionary politician protests against the old economical and social regime, which slays the free spirit of humankind, a revolutionary artist protests against old academic and frozen forms, which have grown out of capitalism, and rather moves toward the new, fresh forms of art.15

She was active in Riga twice. The first period was during 1920 and ’21, when she collaborated with the amateur and workers’ theater collectives affiliated with Riga People’s High School. This work culminated in the mass open air theater play Faces of the Century, written by Leons Paegle, in line with the theories of Platon Kerzhentsev and Evreinov’s large-scale reenactments. In 1925 and ’26, she worked with the drama section of the Riga Unions’ Central Bureau and major left-wing Latvian literary figures such as Linards Lacēns, Leons Paegle, and Andrejs Kurcijs, who were prolifically experimenting with original forms of agitprop and proletarian and political theater, including “disputes” and “charades.” Articles by Lācis in local leftist magazines, together with Lacēns’s classic collection of Latvian political love poetry, Ho-Tai, bear a particular testimony to that moment. This period of Lācis’s career has been subsequently coined the years of “the Persecuted Theater.”

Scene 5: Intellectual Nomadism

Her first visit to Germany, in 1922, saw her as a theoretically mature flag bearer of a successful revolution, which led to her meeting with major German intellectuals, including Fritz Lang. It is there that the transnational constellation around her started to take shape.

Through a young theater director of Austrian descent, Bernhard Reich, who was engaged with the Max Reinhard theater, Asja discovered Berlin, its cultural circles, its theaters (Volksbühne), and its more politicized literary, proletkult, and agitprop theater groupings. In 1923, Asja and Reich went to Munich, where he was supposed to work on a new play. Twenty-four-year-old Bertolt Brecht was impressed by her extensive knowledge of Soviet dramaturgy and invited her to become his assistant for staging the mass scenes of The Life of Edward II of England, as well as to perform the role of the young Edward, the son of the king.16

Remembering her days in Munich, Asja wrote:

Also this city of wide alleys and luxurious white buildings had its narrow and untidy side streets. In one of such streets, in a tiny dark and damp apartment lived Brecht. Here, heated up discussions were taking place, new projects were coming to the fore, new tempting and original ideas about art originated. Among the regulars of this “Brecht’s Club” you would find his collaborator and painter Casper Neher, directors Erich Engel and Reich, the outstanding writer Lion Feuchtwanger and by the way also me.17

Their collaboration and friendship continued throughout their lives. Later, Brecht would go on to elaborate on some of Lācis’s pedagogical inputs into his Lehrstücke form. In 1929 he wrote: “Only a new purpose can lead to a new art. The new purpose is called pedagogics.”18 It was also through her, Reich, and later Tretyakov that he kept himself constantly updated on Soviet developments. Asja also maintained longterm relationships with other members of Brecht’s circle, such as composers Paul Dessau, Hans Eisler, Kurt Weill, writer Elisabeth Hauptmann, and actress Helene Weigel, among others.

Her meeting with Piscator, meanwhile, provided ideas that Lācis later incorporated into her own theater practice. She was a witness and learned from Piscator’s technologically complex set designs and particular stage management.

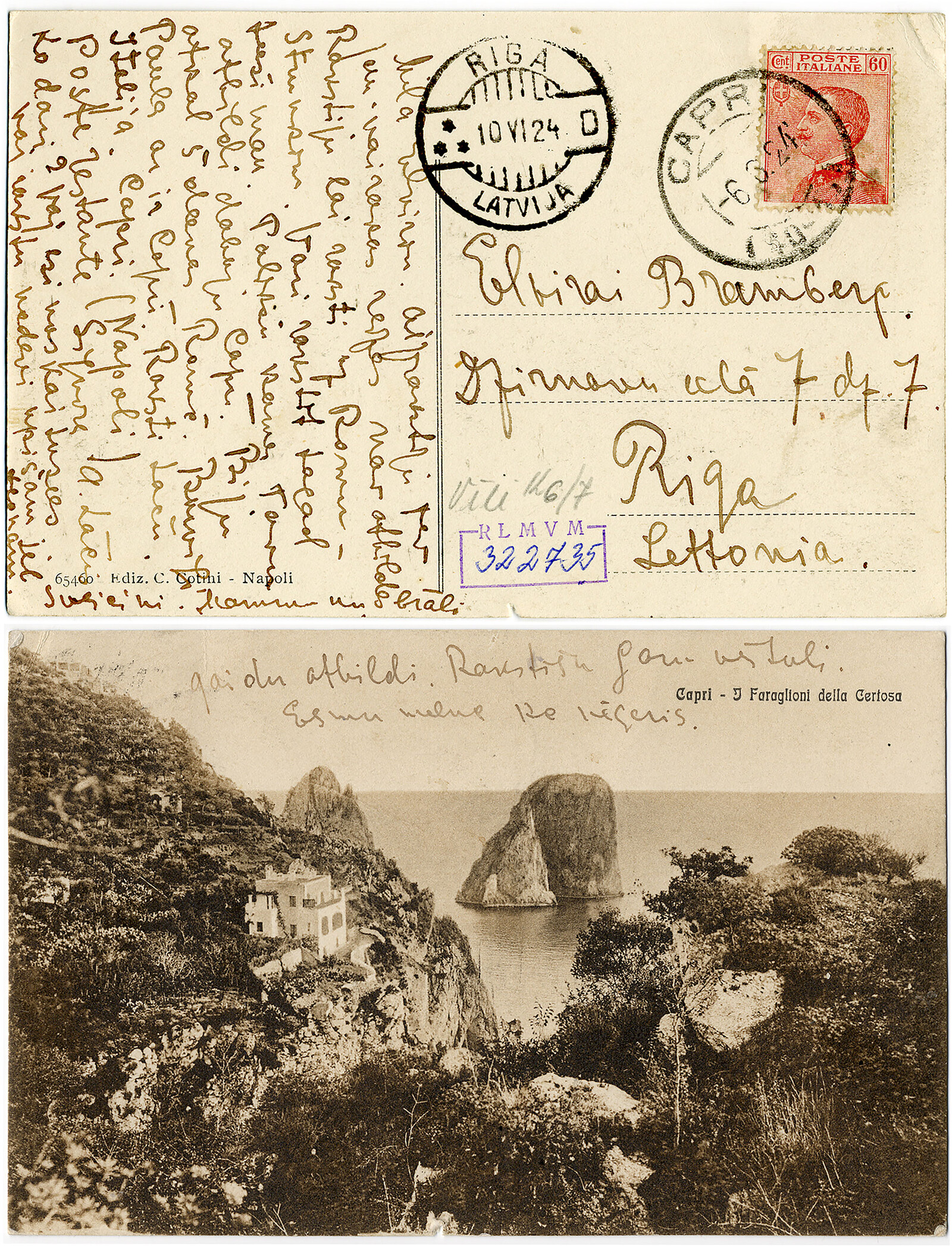

Scene 6: Capri and Naples: Almonds, Revolution, and the Birth of a Critical Theory

A postcard from Capri in 1924 informed Asja’s friend, actress Elvīra Bramberga, that she had settled on the island due to the illness of her daughter, Dagmāra (Daga). Bernhard Reich, who accompanied them, soon had to leave to Paris for work. On Capri she experienced futurist poetry readings by Marinetti, rubbed shoulders with Maxim Gorky and the Russian intellectual diaspora, paid visits to Brecht on Positano, explored Naples, Pompeii, the Amalfi Coast, and Sorrento, and also ran into an unexpectedly significant friendship:

I often went shopping with Daga around the Piazza. One day I wanted to buy some almonds in a store; I didn’t know the word for almonds in Italian, and the salesman didn’t understand what I wanted from him. Next to me stood a gentleman, who said, “May I help you, Madam?” “Please,” I said. I got the almonds and turned back to the Piazza with my packages. The gentleman followed me and asked, “May I accompany you and carry your packages?” I looked at him and he went on: “Allow me to introduce myself— Doctor Walter Benjamin” … My first impression: glasses that threw out light like little headlights, thick dark hair, a slender nose, clumsy hands— he had dropped the packages. On the whole, a solid intellectual—one of the well-to-do. He accompanied me to the house and asked if he might visit me.19

It is enough to read further chapters of her book Profession: Revolutionary to immediately grasp both Lācis’s intellectual weight and her impact on Benjamin:

I told about my Children’s Theater in Orel. About my work in Riga and Moscow. Benjamin immediately supported the idea of a proletarian children’s theater and became inflamed for Moscow. I had to tell him in detail not only about the Muscovite theater, but also about the new socialist customs, the new writers and poets: I named Yuri Libedinsky, Isaac Babel, Leonid Leonov, Valentin Kataev, Alexander Serafimovich, Mayakovsky, Aleksei Gastev, Vladimir Kirillov, Mikhail Gerasimov—I talked about Alexandra Kollontai and about Larissa Reissner.20

Their copublished article “Naples,” which appeared in Frankfurter Zeitung on August 19, 1925, condenses this productive exchange. Written as a set of literary Denkbilder (thought images), this reflection on the “theatricality” of everyday life brings forward the metaphors of “constellation” and “porosity” that later became crucial philosophical concepts applied by Adorno, Benjamin himself, Kracauer, and others. Lācis offered Benjamin what he himself defined as “an intensive insight into the actuality of radical communism.”21 This fusion of politics and life remained an essential element of Benjamin’s relationship with communism.

Posthumously, the curators of the Benjamin estate, and editors of the first edition of Complete Writings, Gershom Scholem and Theodor W. Adorno, decided to remove Asja’s name as a coauthor of “Naples,” doubting her contribution. Apart from Lācis’s claim of having made the observation about porosity, the theatrical references in the article speak for themselves:

Porosity results not only from the indolence of the southern artisan, but also, above all, from the passion for improvisation, which demands that space and opportunity be preserved at any price. Buildings are used as a popular stage. They are all divided into innumerable, simultaneously animated theaters … What is enacted on the staircases is an advanced school of stage management. The stairs, never entirely exposed, but still less enclosed in the gloomy box of the Nordic house, erupt fragmentarily from the buildings, make an angular turn, and disappear, only to burst out again.22

The recently published book Adorno in Naples: The Origins of Critical Theory by Martin Mittelmeier provides an exhaustive account of other members of what Benjamin called an “itinerant intellectual proletariat” (GS, 3:133) dispersed throughout the gulf of Naples. To name just a few figures from this group: young Adorno, who arrived in Naples in the company of aspiring political journalist Siegfried Kracauer; theoreticians Alfred Sohn-Retel and Ernst Bloch; Bertolt and Marianne Brecht; the set designer Caspar Neher; director Bernhard Reich; the designer and illustrator of Stefan George’s books, Melchior Lechter; and Benjamin’s nemesis from afar, Friedrich Gundolf.

According to Mittelmeier, it is in the middle of the exotic “theater of everyday life” of Capri and Naples (not Berlin), amidst philosophical and theoretical confrontations and quarrels between Benjamin, Sohn-Retel, Bloch, Kracauer, Adorno, and Lācis, that the birth of a new critical theory took place. It is also, perhaps, the same latitude from which the later malice of Adorno, Bloch, Kracauer, and Scholem towards Asja originated.

Scene 7: Stereoscope and Tears on Tverskaya

Benjamin followed Asja to Riga in 1925 and to Moscow in 1926, capturing his passionate nomadism in numerous fragments of his One-Way Street and “Moscow Diaries.”

I had arrived in Riga to visit a Woman friend. Her house, the town, the language were unfamiliar to me. Nobody was expecting me, no one knew me. For two hours I walked the streets in solitude. Never again have I seen them so. From every gate a flame darted, each cornerstone sprayed sparks, and every street-car came toward me like a fire engine. For she might have stepped out of the gateway, around the corner, been sitting in the streetcar. But of the two of us I had to be, at any price, the first to see the other. For had she touched me with the match of her eyes, I should have gone up like a magazine.23

Benjamin’s surprise arrival in Riga was at odds with Lācis’s busy schedule and engagement with political theater in Riga. Yet, his letters testify that he worked on his translation of Proust‘s Sodom and Gomorrah there and that during his more than month-long stay he observed and started to love the city, as he mentions in his “Unpacking My Library.”

In 1926, after receiving news about Asja’s neurological illness, Benjamin headed towards Moscow. For two months (December 6–February 1), he observed Soviet cultural life and met its most important cultural representatives. These observations are summarized in his articles “Moscow,” “Russian Toys,” and “Moscow Diaries.” The latter, perhaps not intended for the public eye, was published only after Lācis’s death (a decision made by Adorno and the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research), thus depriving her of any possibility to answer. A great deal of her stereotypically negative depiction by Benjamin scholars derives not so much from the diary itself, but from the tendentious remarks by Gershom Scholem and quotation of its various fragments frequently taken out of context.

Benjamin had come to Russia with the thought of commitment, both to Asja Lācis and the Communist Party. Why he hesitated to make more concrete decisions is yet another story. His description of Moscow and the communist realm, though, remains amongst the most lucid analyses of the century. He describes an emotional farewell to Lācis and the city:

I asked her to hail a sleigh. As I was about to get in, having said good-bye to her one more time, I invited her to ride to the corner of Tverskaia with me. I dropped her off there, and as the sleigh was already pulling away, I once again drew her hand to my lips, right in the middle of the street. She stood there a long time, waving. I waved back from the sleigh. At first she seemed to turn around as she walked away, then I lost sight of her. Holding my large suitcase on my knees, I rode through the twilit streets to the station in tears.24

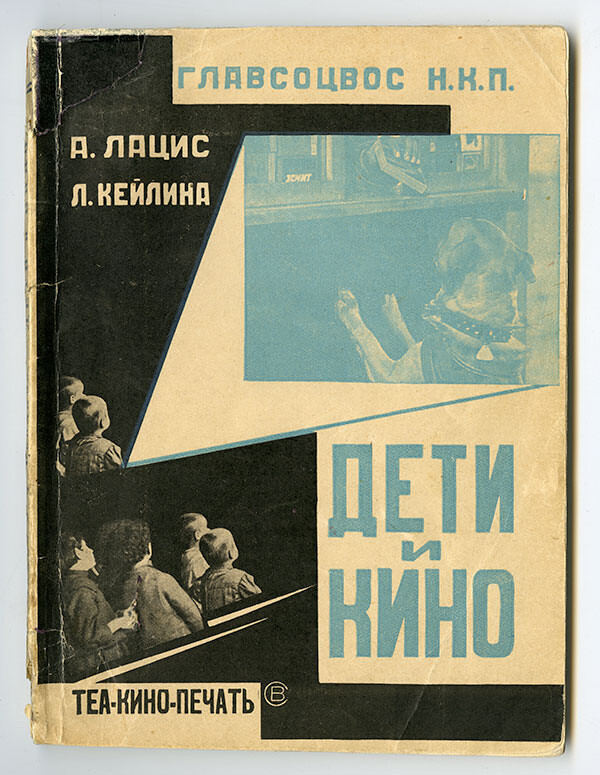

A. Lācis, L. Keilina. “Children & Cinema” (Дети и кино). Graphic Design: Varvara Stepanova. Moscow, Leningrad, publishing house Теа-кино-печать, 1928. Collection of the author.

Scene 8: Children and Cinema

Between 1925 and ’26 Asja got involved in yet another educational project, this time the experimental community playgrounds for children in Moscow. In between, she had accompanied Ernst Toller during his stay in Moscow as a translator and his guide. In 1928, her interest shifted toward children’s cinema, and she worked on the subject in close collaboration with Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya. One of the first cinema theaters for children in Moscow was opened in the facilities of the old cinema Balkan. She involved nearby besprisorniki and created a community of children who managed the functioning of the cinema, chose repertoire, and promoted and reviewed films.

Her research on media influence on younger generations preceded and overlapped with Benjamin’s research on media for his essay on “The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Her book Deti i kino (Children and cinema), cowritten with Ludmilla Keilina and published in Moscow in 1928 with a cover and graphic design by Varvara Stepanova, remains a singular contribution on the subject.

During these same years she became part of RAPP (Russian Proletarian Writers’ Association—РАПП, Российская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей). Due to internal discord, this group split into another group called Proletarian Theater (Пролетарский театр). Eugenia, the wife of Bill-Belotserkovsky, recalls their heated meetings:

People started to gather late in the evening and dispersed only with the morning light. They were reading plays, discussing, and always quarrelling. Asja, as we were calling her, was keeping in line with men and I noticed that everyone was respecting her and took her opinions very seriously … She was speaking not just passionately, but was always able to sustain what she thought was right with a solid argumentation.25

Samizdat Edition Walter Benjamin. Berlin, publishing house “Anleitung fur eine revolutionare Erziehung herausgegeben vom Zentralrat der sozialistischen Kinderladen, West Berlin”, Nr. 2, 1968. Collection of the author.

Scene 9: Cultural Bolshevism in Weimar and the Birth of the Frankfurt School

Asja returned to Berlin in 1928 as the official representative of the Soviet trade mission in Germany for children’s and documentary cinema, organizing presentations of Soviet culture and film, including Kino-Eye works. She passed most of her time in the company of three Bs: Brecht, Johannes R. Becher, and Benjamin, with whom she lived at the time. During the latter half of 1929, Benjamin began doing frequent broadcasts for children at stations in both Frankfurt and Berlin. Asja brought Benjamin to meetings of revolutionary proletarian writers in workers’ halls and to a series of performances by proletarian theater groups, and he introduced her to his childhood Berlin. Asja joined rehearsals of Brecht’s Happy End, and both her and Benjamin remained close to his circle. Her conference on Soviet theater at the German Union of Proletarian Writers was published in Die Scene—Blätter für die Bühnenkunst (no. 5, 1929) and her lectures spread interest about the theater work of Bill-Belotserkovsky, who later got invited to Frankfurt. At the request of Johannes R. Becher and Gerhard Eisler from the Karl Liebknecht Haus, Benjamin would complete a “Program for a Proletarian Children’s Theater,” for Lācis. His attempt to divorce Dora Benjamin and marry Lācis in order to extend her permit of stay failed. In their history of Walter Benjamin, Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings describe Lācis’s health difficulties and the birth of the Frankfurt School as follows:

As she was preparing for her return to Moscow, Asja Lācis suffered a breakdown similar to the one that had incapacitated her in Moscow in 1926. Benjamin put her on a train to Frankfurt to be treated by a neurologist who ran a clinic there. On trips to Frankfurt in September and October, during which he not only saw Lācis but gave several radio talks, Benjamin began to intensify his intellectual exchanges with Adorno … A small group soon formed around Benjamin and Adorno in Königstein, a resort town in the Taunus Mountains. Sitting around a table at the “Schweizerhäuschen,” Benjamin, Lācis, Adorno, Gretel Karplus, and Max Horkheimer engaged in discussions concerning key concepts of Benjamin’s work, such as the “dialectical image.” These “Königstein conversations” left an imprint on the thinking of all the participants and helped shape what became known as the Frankfurt School of cultural theory.26

Scene 10: Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears

Upon her return to Moscow, Lācis continued her pedagogical work and was appointed as a director of the professional Latvian theater Skatuve in Moscow. Among the plays she directed, her version of Peasant Baez by Friedrich Wolf was premiered with the author and Piscator in the audience. An article in which Piscator praises Lācis’s dramaturgical approach was published in Pravda on May 7, 1934. Asja lived with Bernhard Reich, frequently greeting Brecht and other foreign friends who visited the USSR. She enrolled at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VgiK) and started postdoctoral studies at the Lunacharsky Institute for Theater in 1933. Throughout the thirties she continued her pedagogical work and was engaged with Latvian theater groups in Smolensk and Kislovodsk. Piscator involved her as an assistant for his large-scale cinema production of Revolt of the Fishermen, written by Anna Seghers. She contributed extensively to magazines such as Soviet Theater, MORT, Molodaja Gvardija, International Theater, Domas, and Celtne. Due to historical events in Germany, the anti-fascist spirit was another unifying and strong motivating factor for her to remain active.

Scene 11: The Avant-Garde Comes to a Standstill

A photograph shot in Moscow around 1932, on the occasion of Bertolt Brecht’s first visit to the USSR to present his film Kuhle Wampe, depicts: filmmaker Slatan Dudow, poet Semjon Kirsanov, writer Sergey Tretyakov, theater directors Bertolt Brecht, Bernhard Reich, and Erwin Piscator, actor Erwin Deutch (probably), and Maria, the wife of Platon Kerzhentsev. In the center is Anna Lācis with her daughter, Dagmāra Ķimele (Daga), to her right.

In 1935, a similar but extended group, including Eisenstein, Meyerhold, Tretyakov, and Gordon Craig, united for the last time when Chinese actor Mei Lanfang visited Moscow and St. Petersburg. The traditional Chinese theater thus became the last utopian stimulus for the avant-garde generation that was at odds with the new doctrine of socialist realism. Chinese theater resonated strongly with Brecht and his V-effekt (alienation effect), with Meyerhold, and with others.

The Moscow constellation including Margarete Steffin, Carola Neher, Reich, and Lācis were hearing Brecht performing his “Ballad of the Dead Soldier” on the guitar for the last time. He made his next unwilling brief stopover only in May of 1941 on his way towards Los Angeles, offering to intervene on behalf of Lācis when he learned of her arrest and detention.27 Other friends such as Tretyakov had already disappeared by that time. With the beginning of the Moscow Trials and Nazi atrocities, those times in 1935 were the last happy moments of the Heftige Jahre (violent years).

Like numerous other intellectuals of her time, and most members of the above-mentioned constellation, Lācis would be accused and arrested on false charges by the Russian secret police in 1938. Names of her German peers resurfaced in her acts of accusation as well as later in those of Bernhard Reich. She served her sentence first in Butyrka prison and then at forced labor camps in Kazakhstan. Her biography simply states: “I had to spend some time in Kazakhstan.” Little is known of that period in her life, apart from the fact that she was able to organize a women’s theater collective in the prison camp, notwithstanding its extremely harsh and physically exhausting conditions.

Upon her release from prison in 1948, Lācis moved to Valmiera, Latvia, where she worked as the director of the Valmiera Drama Theater until her retirement in 1958. Only after her rehabilitation did she manage to reestablish contact with Brecht and find out Benjamin’s fate. Late in her life she reunited with and married Bernhard Reich, and finally officially joined the Communist Party. During her retirement she worked on her memoirs and theoretical articles in Russian, Latvian, and German. Lācis passed away in 1979.

Epilogue

The book Revolutionär im Beruf: Berichte über proletarisches Theater, über Meyerhold, Brecht, Benjamin und Piscator (Revolutionary at work: Reports on proletarian theater, Meyerhold, Brecht, Benjamin and Piscator; published in Munich in 1971) would become Lācis’s only “Western” publication, translated as it was into Italian, French, and Spanish. The work came into being through a series of interviews and letters published in Hildegard Brenner’s magazine. Brenner belonged to the Brecht’s circle. This material was later edited by Lācis and included a partial reprint of her previously published Russian book on German revolutionary theater (Revolucionnyj teatr germanii [German revolutionary theater], published in Moscow in 1935). If it were not for this rediscovery through Brenner, Lācis’s work might have remained largely unknown to Western scholars. The relative isolation of Cold War Latvia kept these two worlds distinctly separate, too.

The 1960s saw a renewal of interest in her work, coinciding with polemics about the management of Benjamin’s estate by Adorno and Scholem. Hannah Arendt and Jürgen Habermas both publicly expressed their disapproval. Mismanagement of the Institute for Social Research did not just concern Lācis, but also Brecht and everything Benjamin had to do with both.

Tragicomically, Lācis and Reich would meet Brecht again in Moscow on the occasion of the assignment of Stalin (Later Lenin) Peace Award to him in 1954. The surviving members of our constellation met once again in Moscow. Brecht provided information that Piscator was involved in important pedagogical work, and together they mourned the fate of their friend Walter Benjamin, grief over which Brecht had expressed in two poems. Having experienced so many tragedies, they still kept faithful to their common cause.

After Brecht’s death, Lācis and Reich were later invited to visit the DDR for a series of commemorative events at the Berliner Ensemble. There they became acquainted with a younger generation, in particular Heiner Müller. The Berliner produced a commemorative kerchief for the occasion, with a drawing by Picasso in its center, and the phrase “Peace to all nations” written around its four sides in German, Russian, English, and other languages, but also Latvian.

It is through the writings and practices of Brecht and Benjamin, the teaching of Piscator, and the rediscovery of Lācis’s work that their interrupted practices were revived and passed on to younger generations. It is perhaps not fully an accident that Judith Malina and Julian Beck from the Living Theater met at the Piscators’ Dramatic Workshop at the New School for Social Research in New York (Malina’s The Piscator Diaries is a beautiful account of that time). The Brecht/Piscator/Lācis tradition also expanded towards Latin America through Paolo Freire and Augusto Boal, among others.

In 1973, Jack Zipes, polyhedric author of books dealing with childhood education and theater, made Lācis’s Memoir, which recounts her Orel experience, available for English readers in Performance magazine. It was published together with the first translation of Benjamin’s “Program for a Proletarian Children’s Theater,” in collaboration with Susan Buck-Morss. No further materials were made available in English after that.

A serious reevaluation of Lācis’s work therefore is only in its initial phase. Those who have contributed notably in recent years include Beata Paškevica, Susan Ingram, Martin Mittelmeier, Lígia Cortez, and Latvian theater director Māra Ķimele (the granddaughter of Asja Lācis), among others. Hopefully this process will develop and continue. The author of this text has personally contributed by curating three exhibition projects in recent years: “Archives of Anna ‘Asja’ Lācis,” Documenta 14, Kassel, 2017; “Asja Lācis: Engineer of the Avant-Garde” at the National Library of Latvia in Riga, 2019; and “Signals from Another World: Asja Lācis and Children’s Theater” in AVTO Istanbul, 2019. He is also working on a book about Lācis in Italian.

I will conclude with an imaginary conversation between Adorno, Brecht, and Benjamin. It begins with Adorno commenting on Brecht’s concept of the interventionist politics of art: “What drew Benjamin to dialectical materialism … was no doubt less its theoretical content than the hope of an empowered collectively legitimized form of discourse.”28

A legitimate answer to this could be the following affirmation from Brecht: “With the learning-play … The theater becomes a place for philosophers, and for such philosophers that not only wish to explain the world but wish to change it.”29

Benjamin’s clarification in a letter to Gretel Karplus, where he talks about his friendship to Brecht, could conclude the conversation:

What you say about his influence on me reminds me of a significant and continually repeated constellation in my life … In my existential economy, a few specific relationships do play a part, which enable me to maintain one, which is the polar opposite of my fundamental being. These relationships have always provoked more or less violent protests on the part of those closest to me … In such cases I can do little more than ask my friends to have a confidence that the rewards of these connections, whose dangers are obvious, will become clear.30

Lācis’s theatrical and pedagogical approach, which emerges clearly through her texts, her work, and the constellation that formed around her, perhaps help to make this clear. All members of this “dangerous” grouping were trying to grasp a synthesis of life, aesthetics, and politics in their own way. By looking at their intertwinings, the rewards of their connection are self-evident. As Lācis herself noted: “In times of struggle, art has to be both an ally and friend of those in conflict.”31

Our present global circumstances of crisis, shock, and a permanent state of emergency—all lucidly foreseen by Benjamin—with entire generations deprived of the right to self-determination and forced to face extreme violence, oddly resemble the identical historical moment that Lācis and her friends faced a century ago. What this genealogy can teach us, then, is perhaps the fact that today, more than ever before, it is exactly in the “ruins of yesterday where today’s riddles are solved.”32

Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (MIT Press, 1999), 285, 286.

Buck-Morss, Dialectics of Seeing, 286.

Jean-Michel Palmier, Weimar in Exile: The Antifascist Emigration in Europe and America (Verso, 2017), 3.

Leon Trotsky, My Life (Dover Publications, 2007), 212, 213.

Katherine Eaton, “Brecht’s Contacts with the Theater of Meyerhold,” Comparative Drama 11, no. 1 (Spring 1977): 3–21.

Aleksandr Bogdanov, “The Proletarian and Art” (1918), in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism 1902–1934, ed. John E. Bowlt (Viking Press, 1976), 176, 177.

Walter Benjamin, “Berlin Chronicle,” in Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931–1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Belknap Press, 1999), 614.

Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (NLB, 1979), 45.

Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark Times (Harvest Books, 1968), 167. Original sentence: “And there is indeed no question but that his friendship with Brecht—unique as here the greatest living German poet met the most important critic of the time, a fact both were fully aware of—was the second and incomparably more important stroke of good fortune in Benjamin’s life.”

Please see Margarita Miglāne, Silvija Freinberga, Marija Adamova, Anna Lācis, Anna Lācis. (Liesma, 1973); Beata Paskevica, In der Stadt der Parolen: Asja Lācis, Walter Benjamin und Bertolt Brecht (Klartext Verlag, 2006).

Margarita Miglāne, Silvija Freinberga, Marija Adamova, and Anna Lācis Anna Lācis (Rīga: Liesma, 1973), 23.

Asja Lācis, “A Memoir,” trans. Jack Zipes, Performance 1, no. 5 (March–April, 1973): 24–27.

Lācis, “A Memoir.” Original book: Asja Lācis, Revolutionär im Beruf: Berichte über proletarisches Theater, über Meyerhold, Brecht, Benjamin und Piscator, ed. Hildegard Brenner (Munich: Rogner & Bernhard, 1971, 1976).

Walter Benjamin, “Program for a Proletarian Children’s Theater,” trans. Rodney Livingstone, in Selected Writings Volume 2, Part 1, 1927–1930, ed. Howard Eiland, Michael W. Jennings, and Gary Smith (Belknap Press, 2005), 201–7.

“Signals from Another World: Proletarian Theater as a Site for Education: Texts by Asja Lācis and Walter Benjamin, with an Introduction by Andris Brinkmanis,” South Magazine, no. 9 (Documenta 14, 2017) →.

Anna Lācis, Dramaturģija un Teātris. Brehts, Piskators, Laicēns, Grigulis, Brodele (Latvijas Valsts Izdevniecība, 1962), 235.

Anna Lācis, Dramaturģija un Teātris: Brehts, Piskators, Laicēns, Grigulis, Brodele (Riga: Latvijas Valsts Izdevniecība, 1962), 234.

Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theater, ed. Marc Silberman, Steve Giles, and Tom Kuhn (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 57.

Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life (Belknap Press, 2016), 204. Original quote from Lācis, Revolutionär im Beruf.

Lācis, Revolutionär im Beruf, 45–46.

Quoted in Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin, 204.

Walter Benjamin, “Naples,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978), 166–67.

Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, 68–69.

Walter Benjamin, “Moscow Diary,” October, no. 35 (Winter 1985), 121.

Miglāne, Freinberga, Adamova, and Lācis, Anna Lācis, 45–46.

Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin, 332–33.

Helen Fehervary, “Art Instead of Romance: Brecht’s Collaborations with Women,” in The Brecht Yearbook / Das Brecht-Jahrbuch 41, Urlaub Per, Imbrigotta Kristopher, and Rippey Theodore F., eds (Boydell & Brewer, 2017) 185–197

Quoted in Erdmut Wizisla, Benjamin and Brecht: The Story of a Friendship (Verso, 2016), 15.

Brecht, Brecht on Theater, 145.

Quoted in Wizisla, Benjamin and Brecht, 10.

“Signals from Another World,” South Magazine.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Howard Eiland (Belknap Press, 2003), 933.

Category

Subject

The author thanks Adele Bea Cipste (New York University Abu Dhabi) for her help in fact-checking and co-editing this text.