[Institutional critique] has aimed to clarify the legitimate bounds of critique, but in this case, the bounds have been drawn around the type of critique artists could, in good faith, level at the institution of art, while also embodying it professionally, socially, psychically, and economically. This soldered artists and institutions together in an increasingly half-hearted tableau vivant of autonomy, a reconciled realpolitik not all that different from the kind that anointed liberal democracy as the least-worst form of government still standing after everything else has ostensibly been tried.

—Marina Vishmidt, 20171

1.

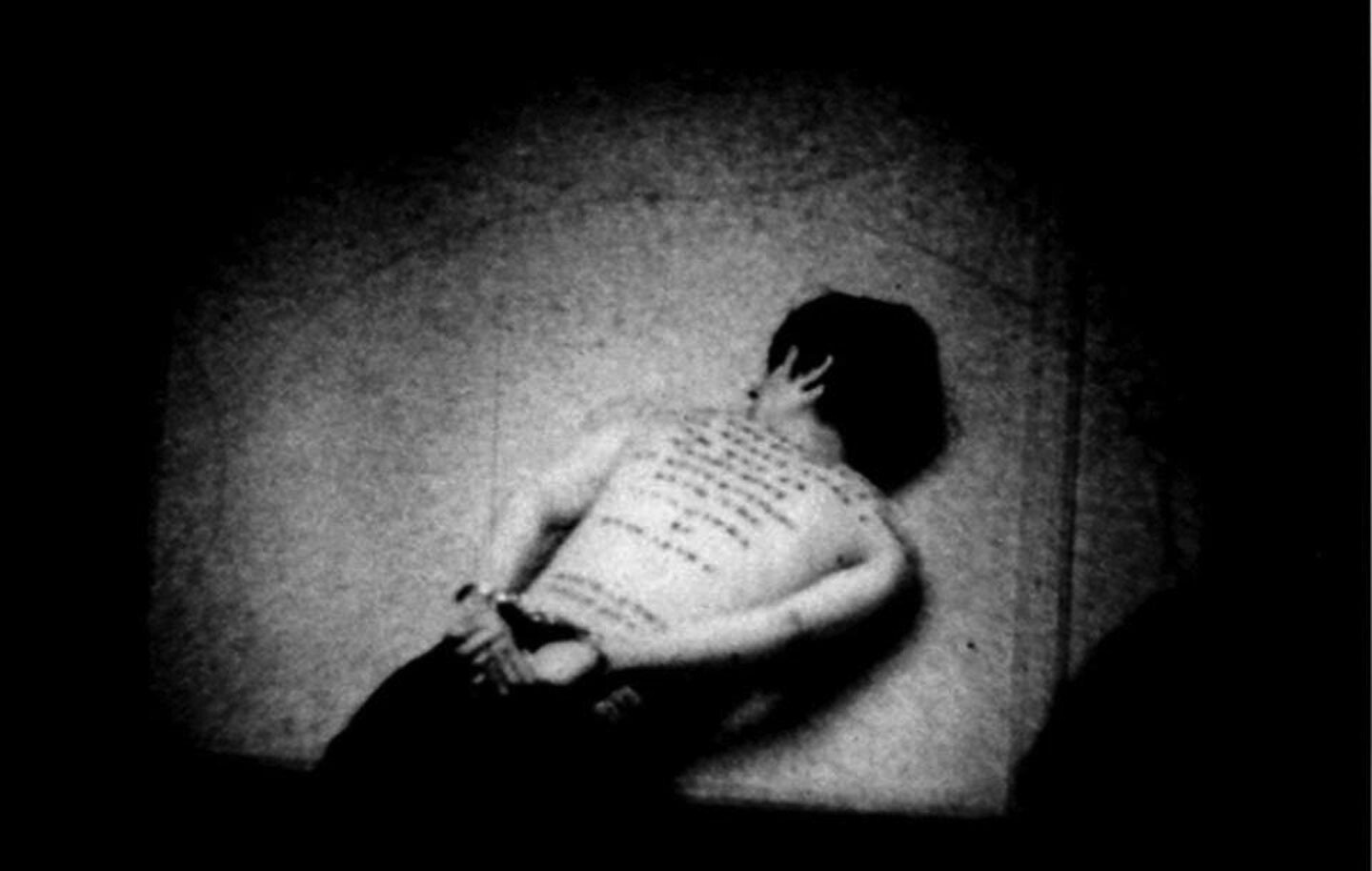

On a cold afternoon in 1975, a young artist took off his shirt and chained himself to the doors of the museum, blocking spectators from entering the Whitney Biennial. After some time (long enough for the museum staff to try and cut the chains), a second entrance was set up, but visitors waiting in line crowded around what they perhaps imagined was a sanctioned performance. On the artist’s bare back his “anti-manifesto” was stenciled, declaring: “WHEN I STATE THAT I AM AN ANARCHIST, I MUST ALSO STATE THAT I AM NOT AN ANARCHIST, TO BE IN KEEPING WTH THE (_ _ _ _) IDEA OF ANARCHISM. LONG LIVE ANARCHISM.”2 Museumgoers ogled and asked questions, which the artist, Christopher D’Arcangelo, was poised to answer. In fact, a central part of this “action” was to engage with museum visitors, to tell them why he was there: a combination of community outreach and political education—something like an explanatory wall label made flesh. He titled the work The Whitney Museum of American Art, and listed his body as one of the materials for the piece.

After opening the other entrance, museum staff brought out folding screens to hide D’Arcangelo, demonstrating the instinct to “remove from view” all that they cannot fit into their curatorial matrix. There is nothing to see here. The screens intended to sap the action of any remaining material power it might have had, especially the conversations with visitors. It was only after they blocked him from view, after an hour of remaining chained in the January cold, that he unlocked himself and left. Jeffrey Deitch remarks that the staff’s decision to cover him up was a “curatorial solution.”3 This solution is just one type of policing that serves to remind us of the museum’s other forms of control that act in concert with other more obvious enforcers of the capitalist social order. Some may read this plainly as a rejection of his gesture of performance, but it’s a more complicated indication of a key function of the culture industry, and creative capitalism generally. To recuperate, to make theirs, the museum must first nominalize the action as a performance and spatialize it. The curators had to bring the folding screens outside and thus expand the museum’s walls to incorporate him. With this, they brought him “inside”—of an extended white cube, and of their preferred mode of presentation. It is only after this neutralization that they could cover him up. His disruption must first be deemed a performance so that it can become a rejected performance.

In the epigraph to this essay, Marina Vishmidt describes the symbiosis between many critical artistic gestures and the institutions that exhibit and historicize them by comparing institutional critique to the illusions of neoliberal democracy. For decades, artists and arts writers have negotiated this mutually beneficial interaction with a theorization of “inside” or “outside” positions with respect to sites of exhibition, display, and presentation. This speculation on the spatial, linguistic, and most importantly political borders of the institution is embedded in many questions that cultural workers have been asking themselves since at least the 1970s: How complicit am I? Can I still critique while inside? How to subvert while maintaining my autonomy? How much autonomy should I relinquish? What is the border between the museum and the statist, racialized, capitalist, neocolonial, gendered violence that produces its material wealth? It’s only more recently that grassroots groups (some including artists) have reframed the last question by acknowledging the border as nonexistent, while incorporating into their tactics the belief in that border exhibited by systems of power.

Though modern art has long speculated—explicitly or not—on the borders of institutions (most obviously with Duchamp and later with happenings, Fluxus, and performance), it becomes particularly pronounced with the advent of institutional critique, and with conceptualism in the late sixties, when this concern was folded into the linguistic conception or documentation of artworks themselves.4 However, some semantic and political inconsistencies have long riddled the discourse. In particular, writing in art from the last decade has worked to untangle two terms and what they are meant to signify: the “dematerialization” of the art object and the becoming “immaterial” of work. Given that the development of post-Fordism and conceptual art occurred around the same time, the two were read as reflections across spheres of art and labor, rather than as contiguous processes in the development of new regimes of work (in visual culture as well). Though many Euro-US artists started to inscribe their art working into labor’s historical development during the Vietnam War era, if only rhetorically, thus breaking with modern aesthetics’ view of art as an activity distinct from labor, art nonetheless continued to be considered exceptional—as commodity, as “unproductive” work, autonomous to capital’s imperative to produce value, even if entangled inside its other structural violence. (Much art theory discourse until recently also failed to differentiate between material wealth and value.5)

Dematerialization, as a conceptual strategy, was and remains rhetorical or semiotic, or realized through performative gestures that correspond to some material act that need not be performed by the artist themselves: Lawrence Weiner scoring the chipping away of a square meter of drywall to be completed by himself or someone else (A 36” X 36” REMOVAL TO THE LATHING OR SUPPORT WALL OF PLASTER OR WALLBOARD FROM A WALL, 1968), Lee Lozano declaring in a notebook that she would no longer make art for a certain period of time (General Strike Piece, 1969), Stanley Brouwn making works by soliciting directions and walking (This Way Brouwn, 1963), an exhibition taking place in a mass-printed book (Seth Siegelaub’s July/August Exhibition, 1970), and so on. Dematerialization was proposed as the negation of material “sellable” objects in favor of the cognitive production of non-objects or other-than-objects. Few were naive enough to assume that non-object-based artistic production wouldn’t leave behind photo documents which could be archived, sold, exhibited; nor did they believe, for example, that Weiner’s cutouts of rugs wouldn’t make it into onto the registrar’s desk. In fact, the possibility of slyly entering commodity and attention markets, or entering a canon for that matter, were often part of the critical strategy itself. Just five years after writing her landmark essay on dematerialization with John Chandler, Lucy Lippard admitted as much in the intro to her anthology Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object.6

Immaterial labor, on the other hand, is not the negation of material labor, nor its undoing, but rather the obscuring of the material conditions guaranteeing production—it is a process of obfuscating work, rather than a stable category of labor.7 Though the use of this term has been heavily, and rightly, critiqued from anarchist and radical feminist viewpoints, especially by feminists of color, it nonetheless continues to be used to essentialize wide types of work into a single category, from unpaid care work to data analysis. Regardless of the term’s validity, the ubiquity of immaterial labor in arts discourse does signal an acceptance of the shift to post-Fordism, as well as to labor’s continual subsumption to capitalism. Furthermore, discourse on both terms has also tended to evacuate labor of key historical traits: immaterial work assumes wide individualization and forecloses labor’s collective potential through invisibilization rather than acknowledging capital and historical production (choosing to rather ontologize labor, as Vishmidt has described), while much discussion of dematerialization seems to omit the aesthetic, material conditions of art itself.

In the mid-sixties, with the emergence of minimal and conceptual art, Euro-US art criticism was preoccupied with a “rat” haunting the gallery.8 For modernist critics like Michael Fried and Clement Greenberg, the rat doing the haunting was the re-reception of Duchamp and his ready-made, implying the evacuation of the artist’s hand, and perhaps, as scholars have since pointed out, the influence of John Cage’s implementations of chance and indeterminacy: in short, an assault on the modernist, formalist functions of art.9 But importantly, there was another vermin: the managerialism guaranteeing that post-Fordist work became flexible, under-waged or unpaid, outsourced, invisibilized. The rat as manager was present in minimal art and conceptualism, just as much as in the office. If Sol LeWitt’s stipulation in “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” reads, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art,” remember Helen Molesworth’s 2003 retort in the catalog of her exhibition Work Ethic: “But machines do not make LeWitt’s wall drawings; assistants do.”10

A more recent ubiquitous question concerns the possibility of withdrawal as a means to critique. Martin Herbert’s 2016 book Tell Them I Said No deals with this in part, tracing some Euro-US artists along what he calls an “axis of absenting.”11 It’s unclear, however, how this vector can accommodate artists who were dropped by the institution, those never allowed “inside” in the first place, or how the slippery term “artist” is adjudicated when the question of legitimacy is destabilized. Graffiti writing was first criminalized, then recuperated, then re-criminalized again along lines of race and class; “folk art” was invalidated as other than art; art by indigenous artists has been reified as anthropological relics, and so on. These outsider classifications are maintained at least until the institution can include such categories in its models of value production, typically under the aegis of liberal representation.

In such a matrix, there are two broad categories applied to artists working in a critical register. The first is “going inside,” with the intention to subvert or usurp the operating protocols of the institution, or to “show the public,” through forms of pedagogy, what is otherwise obfuscated or invisibilized in other domains. Different “waves” of institutional critique have either taken this strategy at face value (Hans Haacke, let’s say), or, following the influence of the social sciences, imagined this posture of mitigating complicity as the only position from which critique is possible—what Andrea Fraser termed “critically-reflexive site-specificity.” The second category, “going outside,” sometimes referred to as “dropping out,” is applied when artists build other institutions, collectively organized/owned or not, or refuse the circuits of art’s commodification. Keti Chukhrov’s description of anti-capitalist critique that operates within capitalist ideology applies to critical art as well. In a forthcoming book she remarks:

The capitalist undercurrent of … emancipatory and critical theories functions not as a program to exit from capitalism, but rather as the radicalization of the impossibility of this exit … The planning and ideological framework is counter-capitalist, but the contents remain either nihilist, or reproduce the status quo of capitalist political economy and sociality in the form of its critique.12

The entrance into the walls, apparatuses, protocols, and functions of the institution depends on defining where a border between inside and out can be constituted: a closed door now opened, a computer server now unlocked, a managerial role now usurped, a philanthropy revenue stream now rerouted. And, most often, the fact that these gestures reify or legitimize the very structure being engaged is taken as inevitable.13

That said, “dropping out,” unlike going inside, continues to be considered a political strategy in itself. Tactics such as boycotts, general strikes, and sabotage, all carrying with them an element of refusal, are consistently welded to the belief that dropping out is possible. But, it’s different in cultural production. As Vishmidt reminds us, the “key significance” of the many generations of institutional critique “was in laying a track between the critique of institutions and critique of infrastructures; that is, not simply the formal but the material conditions that located the institution in an expanded field of structural violence.”14 How does one escape from the field if it determines from where, and how, one begins that very movement? Not just the “social field,” per Bourdieu, but rather the entire cultural landscape that is imaged as other to work?

When we think through this assumed differentiation between calculated subversion and performative refusal, it can be seen to mirror other binary sets of possibilities from Marxian aesthetic theory, social historiography, and postcolonial theory: reform vs. revolution, stadial progress vs. historical rupture, organized labor vs. autonomist self-organization, and so on. How then to avoid the mistaken belief that such vectors of action (going in and going out) take place in wholly different sites of contention, when they operate along one border sketched by the institution itself?

2.

First I wanted to be inside, then I understood that inside the system I would always have to pay. For whatever kind of life, there was always a price to pay.

—Protagonist in Nanni Balestrini’s We Want Everything, 1971

A good place to begin sketching a genealogy of exiting and entering as critique in art is the establishment of the Art Worker’s Coalition (AWC) in 1969—an artist group comprised of cultural workers including Haacke, Lippard, Jon Hendricks, Jean Toche, Lozano, and many others. Most important in hindsight was their popularization of the moniker “art worker” to bridge the spheres of art and labor.15 The catalyst for the organization of the AWC was artist Vassilakis Takis entering Pontus Hulten’s exhibition “The Machine at the End of the Technological Age” (1969) at the Museum of Modern Art and physically removing his exhibited work, which he had asked not to be shown because he felt that it no longer represented his practice. Takis’s attempt to reclaim agency over his production by entering the site of display allowed him to literally disrupt MoMA’s framing mechanisms. Later, AWC and Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG) members similarly entered in front of Picasso’s Guernica to protest the Vietnam War, distributing copies of the now iconic anti-war poster And Babies (1969). Five years later, Tony Shafrazi spray-painted “KILL LIES ALL” on the painting. Such activated entrances, in the way of Takis, GAAG, and Shafrazi, contrast with the predominant exiting of the institution that many conceptual artists in the late sixties attempted by either abandoning their practices, or by literally exhibiting/performing outside of the physical art space as in early post-studio, environment, performance, and video art: Daniel Buren’s Affiches and sandwich men, Robert Smithson’s “non-sites,” Lygia Clark burning her paintings (as many did), the work of BMPT—the list is long.

Historian Alan W. Moore brings attention to a key form of institutional administration that became much clearer in this moment: the hierarchical relationship between the museum that exhibits “critical” art, and the gesture of critiquing itself—in others words, recuperation. He writes: “The AWC undertook a comprehensive interrogation of the role of the museum, which paralleled significant self-examination carried out within the museums themselves.”16 Acknowledging this process at the first meeting of the AWC on April 14, 1969, Jean Toche, cofounder of GAAG, stated that rather than changing museums, the goal of the group should be to “get effective participation in the running of these institutions”—proposing a dictatorship of the cultural precariat, perhaps.17 The cohesion between this sentiment and today’s liberal (or even democratic-socialist) politics is not coincidental, but rather underlines the historical amnesia that guarantees the cyclical calls for appropriating ownership of unjust institutions, rather than abolition. A corollary is the ossification of traditional left formations such as the union as ends in themselves rather than means for waging struggle over the last five decades. In Nanni Balestrini’s account of Italy’s Hot Autumn, for example, we follow a worker who comes to political consciousness, building collective power away from fallible structures in one of the great examples of twentieth century literature that proffers radical theory. Alienated by the class collaboration he sees firsthand in the union (asking workers not to strike), the protagonist has an epiphany: “And who has the pimp’s job of negotiating with the bosses for a few more lire for the worker in exchange for new tools of political control? It’s the union. And it then becomes itself a tool of political control over the working class.”18 The parallel structure in the art world is not the museum worker’s union which agitates, but rather the cultural institution itself which carefully curates performances of critique in its own halls in the spirit of dialogue.

Two later actions by D’Arcangelo demonstrate a form of artistic critique that sidesteps the museum’s liberal protocol just as protesting workers sidestepped the unions during the large wildcat strikes in Northern Italy in 1969–70. In 1975, D’Arcangelo entered the Met. After handcuffing himself to a bench, he proposed that the museum take down all the art and instead allow anybody to enter the museum for seven days and put up their own. He handed out copies of his text “The Open Museum Proposal” in which he also asked the museum to run TV and radio ads to invite people to take part. His proposal—one that would democratize the canon and the space itself—wasn’t accepted. Instead, he was quickly escorted out of the Met’s Great Hall by security guards, taken out of view, and pushed down the steps leading to their offices inside their museum. There, he was arrested and taken away by police.

In another action on March 8, 1978, D’Arcangelo paid to enter the Louvre, removed Thomas Gainsborough’s Conversations in a Park (1745) from the wall and placed it on the floor, leaning against the wall, as if in a collector’s home or in the artist’s studio. In its place, he taped up a manifesto. Here, he undertook operations that are tangential to art’s production (e.g., de-installing a painting and installing a text work) but nonetheless integral to the protocols of art’s sale, presentation, and historicization. Incredibly, he left the museum completely unnoticed. Disturbed by this lack of attention, he published an open letter in Libération where he began to refer to his actions as “demonstrations.” Evidenced by notes in his sketchbooks, he became more aware of how his actions could be recuperated as performances, but “demonstration,” especially in France just a few years after May 1968, imparted his political intention.

Given the radical nature of his actions, D’Arcangelo showed that unsettling museological procedures of value production may be a key element of genuine institutional subversion. Interestingly, many of the museums he struggled against responded with a seemingly peculiar punishment: blacklisting him from entering them in the future. In keeping with the Balestrini reference, perhaps this can be compared with the retribution that bosses in the modern factory took against workers organizing wildcat strikes, when they weren’t paying thugs and mafiosos to physically assault them; as described above, a sanctioned protest operates quite similarly to commissioned critique. The museums’ reactions signaled the dangers they felt in allowing their functions to be destabilized when the gesture of destabilization wasn’t comfortably within the aesthetic registers of the conceptualist artwork. In other words, museums like when artists drop out, but not when they go outside and chain themselves to the building. They like when art critiques its methods of value production from the inside, but not when that value is targeted or put at risk.

3.

You can ask them to imagine [Kafka’s] art as a kind of door. To envision us readers coming up and pounding on this door, pounding and pounding, not just wanting admission but needing it, we don’t know what it is but we can feel it, this total desperation to enter, pounding and pushing and kicking, etc. That, finally, the door opens … and it opens outward: we’ve been inside what we wanted all along.

—David Foster Wallace, 199819

Following the popularization of practices in line with what Andrea Fraser famously termed the “institution of critique” in the nineties, another term that seems to retroactively apply to much critical art is “subversivity,” which philosopher Lieven de Cauter describes as “a disruptive attitude that tries to create openings, possibilities in the closedness of a system.”20 Much of Louise Lawler’s work from the eighties can be said to anticipate this posture. In a 1987 exhibition at MoMA, “Enough. Project 9: Louise Lawler,” she installed three copies of Untitled 1950–51, a photograph that shows the lower half of a Miró painting hanging in the museum. However, the framing focuses on an ultra-polished bench in front of the work bearing a reflection of the painting. In the museum, benches are positioned to quasi-subliminally alert spectators to which works are worth focused contemplation, stimulating value-production via reception. Lawler then placed the same bench in front of her photographs, mimicking the mechanisms of the museum, and in the process, informing the viewer of the technique. One is reminded of Michael Asher’s 1974 installation at Claire Copley Gallery in Los Angeles, which eliminated the wall separating office and exhibition space, exposing the gallery’s operations and similarly re-spatializing the white cube. Even more similar in strategy perhaps are Asher’s contribution to the “73rd American Exhibition” and Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum,21 wherein the act of conforming to the museum’s historical periodization works to destabilize the embedded violence, and in the case of the latter reveals the violence against people of color integral to museum taxonomy and property.

In a 1979 group exhibition with D’Arcangelo, Adrian Piper, and Cindy Sherman at Artists Space, Lawler installed a painting of a racehorse (1863) borrowed from the Aqueduct Race Track. She also installed two very bright stage lights, one directed at the painting and the other toward the viewer. The lights were bright enough to illuminate the street outside as well, including the façade of a Citibank. One key feature often left out of discussions of this show is that Lawler and D’Arcangelo had initially proposed to present all four artists’ work as a single piece.22 When this proposal was rejected by the other artists, D’Arcangelo decided to make himself institutionally invisible. He struck his name from all instances of the show’s title (in the catalogue, in publicity material for the show, and so on), inserting a blank space instead.23 He also wrote a four-page essay that was pasted on the walls—corresponding to four blank pages in the catalogue. Lawler later remarked that the pages of his essay appeared in the room with her installation, confusing spectators: whose work is whose, what is the work, who did the lighting, who is missing, and so on. In her 1982 exhibition at Metro Pictures, Lawler activated the goal of unifying various artists’ objects when she began her “arrangements,” exhibiting work by the gallery’s artists as one piece, pricing it at the total of all the individual pieces, with a 10 percent commission fee for herself. The art system necessities clear forms of attribution and authorship for the sake of producing value, and simultaneously for crafting its own insides and outs: who belongs to the canon and who doesn’t. Though Lawler’s intervention in this instance was a conceptual gesture and not an attack on that value production, it pedagogically sketches the regimes of authorship and lampoons them.

To consider how a relatively benign disruption of protocol can develop further, take Lawler’s production and subsequent reuse of what is perhaps her most famous picture: Pollock and Tureen, Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut (1984). It depicts what is likely Jackson Pollock’s last drip painting hanging in the home of storied collectors in the age when hyper-speculation truly exploded the art market. Only a small portion of the Pollock canvas is included in the image, which captures how the painting is “framed” in the space, hanging just above a Limoges soup tureen.24 This disruptive re-performance of images is most evident when one considers the “medium” designated for another re-performance of Pollock and Tureen in the collection of the MoMA. Here Lawler disturbs the very pinnacle of museological taxonomy: the cataloguing of the art object. MoMA’s website stipulates that Pollock and Tureen (traced) (1984/2013) is comprised of “signed certificate, installation instructions, and PDF formatted file.”25 The objects that the title refers to are rather the iterations that can be printed and installed following the parameters of Lawler’s instructions and a proposed site. However, the individual iterations are contingent upon specific constraints stipulated by the artist’s “hand” (the installation instructions)—an internalization of something akin to the artist’s contract or the score into the work’s medium itself.

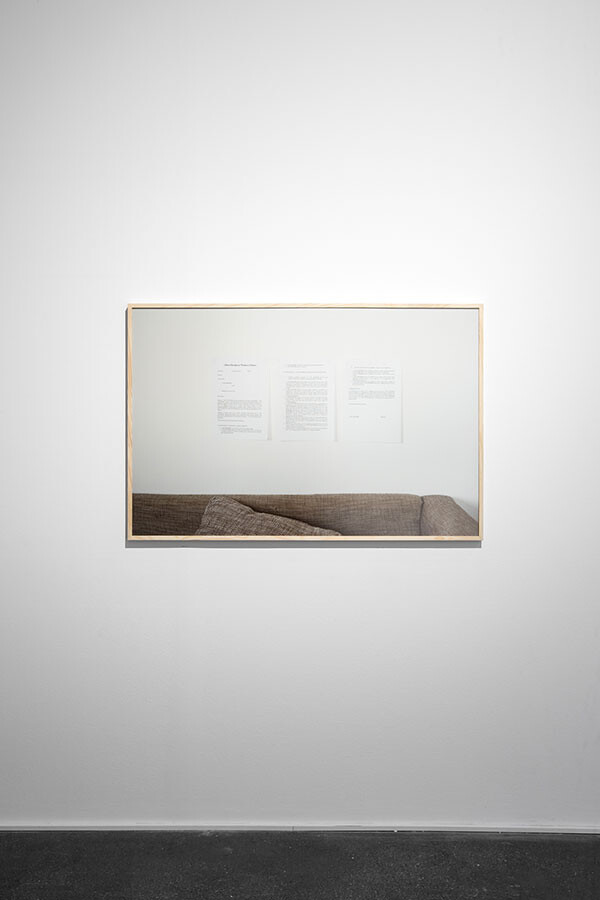

Yazan Khalili, I, The Artwork, 2016. Framed photographic print 120 x 79.2cm. Installation shot at Lawrie Shabibi gallery, Dubai, 2017. Yazan Khalili in collaboration with Martin Heller. Commissioned by Riwaq Biennial with support of Mophradat.

4.

The modes and gestures of conceptualism (refusal of authorship, counter-institutional formations, non-object-based and process-based work) have become the dominant forms of artistic production—or at least of art that is shown in museums. As Ed Halter remarks: “Perhaps we should stop thinking about the failure of conceptualism to transcend the art world, just long enough to notice that it has, in fact, overtaken the world as such.”26 (This allusion to transcending the art world into the world itself carries yet more import when considering political work through or with art, as discussed below.)

The work of artists such as Jill Magid is certainly in this register, but brings up a different problematic implied in entrance/collaboration: Who can enter, and why? For her System Azure Security Ornamentation (2002), for example, Magid approached the Amsterdam police proposing to decorate CCTV cameras with rhinestones. They refused. However, after founding a company and becoming “professionalized,” at least performatively, thus operating in a creative capitalist managerial role, Magid was not only invited but paid by the police to do the same work. The work intends to bring visual attention to the cameras and the pervasive surveillance state they foster. The process of gaining access, however, attests to a privilege that Magid’s whiteness carries within an inherently racist and violent institution such as the police. In this sense, Magid’s work identifies who is “permitted” to critique and who isn’t. While the museum is surely less violent than the police (though the two collaborate), similar privileges determine who can protest and who cannot, or who will be penalized and who won’t.27

Magid’s The Spy Project (2005–10) takes institutional disruption further by engaging with the site of display and a state intelligence agency. After securing a commission by the Dutch Secret Service (AIVD) to produce a work for its headquarters, for three years she met with different employees of the agency and recorded their conversations in handwritten notes, given that sound recordings were not permitted. Her project proposed that she become a member of the organization as a “Head of Service,” “responsible for maintaining the secrecy of sensitive information.”28 Throughout the duration of the project, Magid exhibited sculptures, neons, and works on paper based on the conversations, some of which were censored and confiscated by the police. She also wrote a spy novel. She collected her notes in a manuscript, but was told it would be greatly censored. After arguing, the AIVD conceded that she could exhibit her manuscript “as a visual work of art in a one-time-only exhibition.”29 Afterwards, the book would be confiscated and become property of the Dutch government. Magid recounts this conversation in a novel she later produced from the manuscript, 40 percent of which was redacted:

My advisor interrupts him. What are you proposing?

He directs his answer back to me. We want you to think of the book as an object of art. We will redact it and put it inside the vitrine with your notebooks where it will remain, permanently.

You want me to put it under glass so that it will no longer function as a book but as sculpture? Yes. He blinks his eyes rapidly. It becomes an object of art.30

The AIVD therefore completed the work of art on Magid’s behalf, creating a conceptual text object.31 Climactically, Magid presented the agency’s censorship as a physical performance in her exhibition “Authority to Remove” (2009–10) at the Tate. There, she installed the to-be-confiscated manuscript securely under glass. At the opening of the show, agents entered the Tate and permanently removed the object. In stark contrast to D’Arcangelo, who stealthily entered the Louvre in order to sabotage a work, Magid essentially directed the police to sabotage the work on her behalf, thus demonstrating the diverse levels of accessibility, surveillance, and control guaranteed by institutionality.

If Lawler and Magid’s disruptive propositions rely on the institution to play its part—either in stretching Lawler’s picture beyond recognition (“to scale”), or in literally removing and confiscating a piece of Magid’s show—then Yazan Khalili’s I, The Artwork (2016) instead relies on the museum to disobey his instructions, a different choreography entirely. In this work, the viewer encounters a contract written and signed from the position of the artwork itself, meaning that for all intents and purposes it is null and void. It stipulates, among other things, that the piece—a photograph of the contract hanging on a wall above a sofa—cannot be shown in an institution in a country which is occupying another land or people. Clearly, this work cannot be shown in Israel. The point therefore is to wait for an Israeli institution with liberal views to install it on its walls.32 At that point spectators will come into conflict with their position regarding Israel’s violent occupation of the Palestinian people and land. The disturbance of museum protocol that Khalili activates is predicated on the failure of the contract underpinning it. It disturbs by entering and “failing.”

Courtesy Decolonize This Place.

5.

I finish with another formulation by Vishmidt:

If the project of critique always ends up affirming its subject—the institution of art—in its valorization of both the affective subject and its critical capacity, this can inflate the artist as critical subject beyond all reason, much like how philosopher Theodor W. Adorno deems art a grotesque, inflated “absolute commodity” with no use value in place to stop it from expanding to whatever the market will bear. Only labor can check the infinite expansion of the “automatic subject” of capitalist value in art as elsewhere.33

Given the historical narrative of institutional critique, where has political sloganeering via cultural practice, genuine or not, brought us? This question is especially urgent in today’s context where critique has become enshrined in the highest orders of institutionality, from Google artist residencies to United Nations in-house consultants. How do we critique without relinquishing the self-determination and curating of the work and its public, whether it be art or grassroots organizing? Under a visual culture beholden to capitalist philanthropy for funding and legitimacy, and more expansively, under neoliberal forms of representation (i.e., mainstream identity politics), how can agitation by way of cultural production avoid being defanged and made the spectacle of absorption itself?

The successful ouster of ex–vice-chair of the Whitney Museum Warren Kanders in 2019 provides one possible answer. After sustained action by dozens of grassroots community groups, cultural workers, and museum staff members calling for Kanders’s removal because of his role in producing and profiting from weapons use in settler-colonial occupation and state violence all over the world, he resigned. Much discussed in art magazines the world over, many missed the point. One article, for example, discussed the crucial pressure by Decolonize This Place (DTP) in coalition with anti-displacement groups, anti-jail activists, and many other grassroots groups, but chose to ask this: “As calls intensify for Whitney Museum vice chair Warren B. Kanders to step down, what more can museums do to avoid appointing board members with unethical business ties?”34 Though the campaign was incredibly clear-eyed in its goals—to unseat a violent warmonger so as to destabilize the entire system of private ownership and its incumbent colonial forms of exploitation—why were so many in the art world stuck asking how to reform boards rather than abolish boards? A statement released by DTP in September 2019 is clarifying:

For those who may think that the work we do is to be measured and valued by whether a Warren B. Kanders is removed or a certain curator is hired, or a problematic show is cancelled, etc., fundamentally misunderstands the political project Decolonize This Place is engaged in. We, and all our collaborators, seek collective liberation and are unafraid to unsettle everything. We are accountable to, first and foremost, communities we belong to and not simply the art world, its gatekeepers or funders. We blur the lines between art, activism, academia and organizing to build movements rooted in peoples sovereignty, as we recognize the debts we owe one another, seeking to resist and build together in order to be free. There are always people that are / feel left behind, because they are attached to the status quo, cannot imagine anything else, or simply benefiting from the misery of others as they intellectualize the problem, whether intentionally or otherwise (doesn’t matter). We can understand that and it won’t stop us. Here, we also take the opportunity to make it abundantly clear to all those who wonder (or not): We are for abolition and decolonization, and are anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist without being statist. We also state unequivocally that we are anti-Zionism and Israel as a settler colonial project not dissimilar to the United States, as well as against all other forms of oppression.35

Amidst the campaign to oust Kanders, DTP organized “Nine Weeks of Art + Action,” leading up to the 2019 Whitney Biennial. During the sixth week, a woman artist of color spoke in Spanish and in English in the occupied lobby of the Whitney. She described the connections between Kanders’s war machine and the continued colonization of the Puerto Rican people and land by the US. At one point, she directed our attention up towards the stairs where an employee of the museum filmed the action; she asked us why her work isn’t shown in this “museum of American art” and then reminded us that some years from now, the video of her speech would likely be projected onto the Whitney’s walls, historicizing her protest as another wave of artists’ critique.

As demonstrated by this campaign, entering the institution is still a viable tactic for creating popular power and leveraging it, depending on how it is done, in coalition with whom, and to what ends. As a comrade recently mentioned to me, what is to be done is clearer than how to do it. Most recently, MTL+, along with other groups and collectives, has proposed an “arts of escalation” as one how, which uses the museum as a semi-safe space (with less police presence than the street) to build a struggle.36 This must happen across and through the boundaries sketched by the museum, and especially across the boundaries erected between cultural production and other work. The victory against Kanders was not accomplished alone by the museum staff who penned a letter, nor by the eight artists who boycotted the show by removing their work halfway through the exhibition. The broad coalition was instead a show of how autonomous, abolitionist community groups across New York City “showed up.” Wherever a gesture of critique begins or terminates, it must reject methods of value production and legitimized forms of critique, do away with the separation of art-working and labor, and embrace struggles that aim to erode the need to exit or enter, with the goal of making these spaces ours.

Marina Vishmidt, “Beneath the Atelier, the Desert: Critique, Institutional and Infrastructural,” in Marion von Osten: Once We Were Artists (A BAK Critical Reader in Artists’ Practices), ed. Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert (BAK, 2017), 219.

For more on his manifesto and actions, see the exhibition pamphlet for “Anarchism Without Adjectives: On the Work of Christopher D’Arcangelo,” organized by Sebastien Pluot at Artists Space, New York, September 10–October 16, 2011, available here: →. The statement was written with a marker by Cathy Weiner.

Jeffrey Deitch, “Christopher D’Arcangelo,” in Anarchism Without Adjectives: On the Work of Christopher D’Arcangelo (1975–1979), exh. cat. (Artists Space, 2011), 17.

I use “speculate” here in the way Marina Vishmidt theorizes it in her book Speculation as a Mode of Production (Brill, 2018). In the book, she draws parallels between the processes of speculation in financialization and in art, arguing that neither financialized capitalism nor artistic production can be thought of as unproductive labor.

On this, see the introduction to Dave Beech, Art and Postcapitalism: Aesthetic Labour, Automation and Value Production (Pluto Press, 2019). Marina Vishmidt’s excellent way of countering art’s ostensible unproductiveness is to consider it socially reproductive, as argued in Speculation as a Mode of Production.

Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (University of California Press, 1973).

In a recent discussion on these two terms, Vishmidt remarked succinctly: “all labor is material.” Marina Vishmidt in conversation with Andreas Petrossiants, “Marina Vishmidt: Speculation as a Mode of Production,” e-flux podcast, June 18, 2020, →.

The “rat” reference is to Hal Foster’s The Return of the Real (MIT Press, 1996), 56, where he writes that critics like Michael Fried were worried about minimal art presenting “a self-conscious position on art … but also to intervene in this discourse as art. Again, this is an avant-gardist recognition (Fried smelled the same rat as Greenberg: Duchamp and disciples) … only with minimalism does this understanding become self-conscious. That is, only in the early 1960s is the institutionality not only of art but also of the avant-garde first appreciated and then exploited.” For other discourses happening at the time in minimal dance and music that are also relevant, see the essays by Carrie Lambert-Beatty and Diederich Diederichsen in A Minimal Future? Art as Object 1958–1968, exh. cat. (Museum of Contemporary Art in collaboration with MIT Press, 2004).

See Julia Robinson, “John Cage and Investiture: Unmanning the System,” in John Cage, ed. Julia Robinson (MIT Press, 2011), and the catalog for the exhibition that Robinson organized: The Anarchy of Silence: John Cage and Experimental Art, exh. cat. (MACBA, 2009). See also Branden Joseph Experimentations: John Cage in Music, Art, and Architecture (Bloomsbury, 2016).

Helen Molesworth, “Work Ethic,” in Work Ethic, exh. cat. (Baltimore Museum of Art, 2003), 42.

Martin Herbert, Tell Them I Said No (Sternberg, 2016).

Keti Chukhrov, Practicing the Good: Desire and Boredom in Soviet Socialism (e-flux and University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming 2020).

One outlier, of a few, is the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles, central, in fact, for considering much of what is discussed in this text; specifically her residency at the Department of Sanitation of New York since 1977. See my “Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Maintenance and/as (Art) Work,” View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture, no. 21 (2018) →. Even the scope of her project, which brought attention to the underfunding and horrendous working conditions of sanitation workers, specifically from a materialist perspective, has been recuperated by the austerity government of New York City, which launched a residency program in 2018 to artwash over consistent cuts to social spending while invoking Ukeles’ name.

Vishmidt, “Beneath the Atelier,” 220–21.

See Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (University of California Press, 2009).

Alan W. Moore, Art Gangs: Protest and Counterculture in New York City (Autonomedia, 2011), 26. Emphasis mine.

See Jean Toche’s statement at first AWC hearing printed in: AWC, Open Hearing on the Subject: What Should Be the Program of the Art Workers Regarding Museum Reform and to Establish the Program of an Open Art Workers Coalition (AWC, 1969), statement 1. Primary Information has made this available as a PDF on their website: →.

Nanni Balestrini, We Want Everything, trans. Matt Holden (Verso Books, 2016), 105.

David Foster Wallace, “Some Remarks on Kafka’s Funniness From Which Probably Not Enough Has Been Removed,” in Consider the Lobster and Other Essays (Little, Brown and Company, 2006), 65.

Lieven de Cauter, “Notes on Subversion/Theses on Activism,” in Art and Activism in the Age of Globalization, ed. de Cauter, Ruben de Roo and Karel Vanhaesebrouk (NAi, 2011), 9, referenced in relation to Lawler’s work by Roxana Marcoci in “An Exhibition Produces,” in Louise Lawler Receptions exh. cat. (MoMA, 2017), 28.

See Anne Rorimer, “Michael Asher: Kontext als Inhalt,” available in English here: →; and Martha Buskirk, “Interviews with Sherrie Levine, Louis Lawler, and Fred Wilson,” October, no. 70 (Autumn, 1994): 98–112.

Louise Lawler, in 5000 Artists Return to Artists Space: 25 Years, ed. Claudia Gould and Valerie Smith (Artists Space, 1998), 100–101.

This was another way of “dropping out,” perhaps, though this time he participated in a sanctioned exhibition. In a twisted turn of events, when a retrospective of his work was mounted at Artists Space four decades later, rather than including the title Anarchism Without Adjectives on the banners outside their Tribeca space, the gallery opted for D’Arcangelo’s name, stating that the neighborhood would not take kindly to anarchist sentiments. I thank Sébastien Pluot for bringing this to my attention.

The image has been re-presented in multiple ways: as a gelatin silver print, along with “Pollock and Tureen” printed in red on the image’s mat; as a traced image drawn by the illustrator Jon Buller, printed on paper or on a wall, produced at any size “to scale.” Lawler first exhibited the “traced” works in her 2013 survey at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne. See Louise Lawler: Adjusted, ed. Phillip Kaiser, exh. cat. (Museum Ludwig in cooperation with Prestel Verlag, 2013). Most recently, Lawler has developed another “adjusting” mechanism: “distorted” versions of her images, titled (adjusted to fit, distorted for the times). See Louise Lawler, “Distorted for the Times,” October, no. 160 (Spring, 2017), 152.

“Louise Lawler: Pollock and Tureen (traced),” MoMA.org →.

Ed Halter, “The Centaur and the Hummingbird,” in Free, exh. cat. (New Museum, 2011), 43. Accessed online: →.

One clear and distressing example among many: the New Museum hiring a union-busting firm to intimidate organizing workers, and then firing most of those successful unionists with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, soon after exhibiting the work of Hans Haacke, who has long championed the rights of workers.

Jill Magid, “Becoming Tarden—Prologue,” e-flux journal, no. 9 (October, 2009) →.

Jill Magid, “The Spy Project,” Jillmagid.com →.

Jill Magid, Becoming Tarden (New Museum, 2010); excerpts quoted in Halter, “The Centaur and the Hummingbird.”

I would be remiss not to bring up Marcel Broodthaers’s Pense-bête (1964), in which he exhibited the remaining unsold copies of his book of poetry of the same name affixed in plaster, making the book unreadable. Pense-bête set an early precedence for this type of conceptualist work, which strikingly resembles Magid’s work, if only formally. In Broodthaers’s work, he performatively “quit” his prior work as a poet, and declared himself an artist. If his books wouldn’t be read, he sarcastically asked, perhaps they would be looked at. In Magid’s piece, the book is also unreadable because of its censure by state intelligence.

Yazan Khalili, in interview with David Kim, “I, The Artwork: A Conversation with Yazan Khalili,” e-flux journal, no. 90 (April 2018) →.

Vishmidt, “Beneath the Atelier,” 235.

Cody Delistraty, “The Whitney’s Choice: Can a Museum for ‘Progressive Artists’ Have an Arms-Manufacturer Vice-Chairman?” Frieze, April 12, 2019 →. This is not to single out Frieze, but is just one example of the approach many art magazines took to covering the events.

Statement shared with author via email on September 24, 2019 and released on social media the previous day.

MTL+, “The Art of Escalation: Becoming Ungovernable on a Day of City-Wide Transit Action,” Hyperallergic, January 31, 2020 →.

Category

Subject

My gratitude goes to the many exceptional friends and comrades who read this piece at various stages of completion, too numerous to list. Among them: Christian Xatrec, with whom I am conceptualizing an event to emerge from the text; Louise Lawler and Cathy Weiner for reading a late draft and confirming the historical facts. Thanks as well to Julia Robinson for inviting me to read a very early draft of this text for her class at NYU. Nicholas Martin graciously searched through the Fales Library collection while the archive remains closed. I’m grateful to my colleagues at e-flux journal for their support and for all they’ve taught me. I thank Elvia Wilk for editing this piece and thinking through critique with me; without her thoughts and work, the formation of a coherent essay would have been impossible.