We know how the first paragraph begins. We’ve read about the changing climate for over twenty years, infrequently at first and then daily until we couldn’t deny it any longer. The world is burning. The oceans are heating up and acidifying. Species are dying in the Sixth Great Extinction. Koalas have replaced polar bears as the charismatic species whose dwindling numbers bring us to tears.1 Millions are displaced and on the move, only to be met with fences, borders, and death.

We’ve read the news and it keeps getting worse. As pandemics spread, as the climate crisis continues unabated, the imperatives of capital prevent state action on anything but protecting banks and corporations. Since 1988, when human-induced climate change was officially recognized by the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the oil and gas sector has doubled its contribution to global warming. The industry emitted as much greenhouse gas over the twenty-eight years after 1988 as it had in the 237 years since the beginning of the industrial age.2 Regular reports announce that the atmospheric impact of these emissions is manifesting faster than scientists previously expected.3 The IPCC clock tells us that we have eleven years to prevent warming from rising more than 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels. Some places on earth already hit that mark in the summer of 2019.4 “Climate change”—that innocuous moniker preferred by Republican political consultant Frank Lutz and adopted by the George W. Bush administration because “global warming” seemed too apocalyptic5—has moved from seeming far away and impossible to being here, now, and undeniable. This has not stopped the United States and Canada from providing economic relief funds in the wake of coronavirus to oil and gas companies.

Those least responsible for climate change, those who have suffered the most from capitalism’s colonizing and imperial drive, are on the frontlines of the climate catastrophe. How to find clean water amidst never-ending drought? How to gather needed herbs, food, and firewood amidst rapid deforestation? How to survive the floods and fires? Centuries of colonialism, exploitation, and war undermine people’s capacities to survive and thrive, hitting poor people, women, children, people with disabilities, already disadvantaged racialized and national minorities, and the elderly hardest of all. According to a UN report, “We risk a ‘climate apartheid’ scenario where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer.”6 Capitalism has always permitted some to flourish by forcing others to fight for survival. The climate crisis—and now the coronavirus—intensifies these dynamics into a global class war. In Marx’s words, “ruin or revolution is the watchword” for our times.7

Koala poses for the camera in Vivonne Bay, Kangaroo Island, South Australia, Australia. Photo: Chris Fithall/CC BY 2.0

After Denial

Such a sharpening of the contradictions should prove politically invigorating. It hasn’t so far. The old division between climate-change deniers and the reality-based community has broken down, but a new one has yet to take political form. Even as the Trump administration works to dismantle environmental protections, particularly Obama-era regulations aimed at reducing emissions, the establishment recognizes global warming. From the United States Department of Defense to the global energy and banking sectors, there is wide acceptance of the fact that carbon emissions are leading to increased temperatures. The struggle now is around what to do and who should pay.

The old fight against climate denialism benefitted both sides—which may account for why some continue to struggle on this terrain. Denialism bought time for big carbon, enabling the industry’s massive expansion across North America. Between 2010 and 2012 alone, the Obama administration constructed 29,604 miles of pipeline (enough to circumvent the earth and then some).8 Perhaps less obvious was denialism’s benefit to the environmental movement: opposing climate denial enabled environmentalists to become mainstream and build a broad coalition inclusive of scientists, indigenous rights activists, and proponents of social justice. Allied with science, environmentalists shed their eco-hippy personae to become representatives of a fact-based critique of mass consumption. Commodity culture wasn’t only spiritually deadening; global supply chains’ dependence on carbon-based energy means that unfettered consumption directly impacts life on earth. Standing Rock Water Protectors, to use but one example, pushed the leadership of indigenous people to national and international prominence as they forged collective opposition to pipelines and fracking. Attention to sacrifice zones, slow death, and the persistent deprivations of environmental racism helped environmentalists move beyond the elitist image long associated with conservationism. The patient work of building an alliance against climate change denial and the racist, colonialist, capitalist system it sought to preserve produced an inclusive and rhetorically powerful environmental justice movement.

Although the climate change debate has moved beyond the division between deniers and believers, some progressives remain attached to denial. Instead of fighting on the new terrain produced by widespread acknowledgement of the fact of climate change, they displace denial into their own arguments, shielding themselves from the overwhelming burden of action. While no one seriously denies climate change anymore, progressives have found new—and often quite creative—ways to deny climate change’s true political consequences, guaranteeing that nothing essential has to change.

Progressive Denial

Some progressives have decided that ruin is inevitable. We just need to accept it. These progressives continue to present the most pressing problem now as climate catastrophe denialism. The task at hand, we are told, is psychological. For example, Jem Bendell’s 2018 “Deep Adaptation Agenda” takes the inevitability of societal collapse to be a matter not of physical infrastructure and energy sources but of human values and psychology.9 Climate change is like getting cancer: it forces a massive reevaluation of what is important in life. The failure to accept the climate catastrophe masks a deeper failure to develop a better relation to the earth.

Five years before Bendell published his deep adaptation agenda, Roy Scranton had already presented the task at hand as learning how to die.10 In a Stoicism refitted for the Anthropocene, Scranton argued that we have to accept that there is nothing we can do to save ourselves. This acceptance will enable us to detach ourselves from false hopes and fruitless plans. It will let us free ourselves from fear.

Scranton and Bendell write in terms of a civilizational us, a “we” of shared values, metaphysics, and investment in the privileges of the carbon economy. There’s no class struggle, no inequality of responsibility for or capacity to respond to the fires, droughts, floods, and storms of a rapidly changing planet. Politics disappears, replaced by the individual’s psychological capacity to acknowledge the worst and respond ethically, that is, reflectively.

Less metaphysical, although equally resigned to planetary ruin, is Jonathan Franzen. For Franzen, any hope of avoiding civilizational catastrophe is misguided, even harmful, leading to misplaced efforts and broken dreams. To think that we might build new transportation and energy systems, much less replace capitalist competition with communist planning, is a pipe dream—futile and delusional. We need accumulated capital in order to weather the fires, hurricanes, droughts and other emergencies as they increase in frequency and furor. The best we can do is buttress the status quo, “promoting respect for laws and their enforcement,” while also advocating for gun control and racial and gender equality.11 Our best course, in other words, is to follow the liberal line, not make a fuss, and be sure to remain on good terms with the police. If Bendell’s and Scranton’s embrace of climate catastrophe means that everything changes, Franzen’s means that nothing does. Because there is nothing we can do, there is little to be done, apart from what we would be doing anyway. The little to be done, for Franzen as well as Bendell and Scranton, is to combat climate catastrophe denialism, making sure that people comprehend just how catastrophic the situation really is.

Other progressives have rightly refused to join Bendell, Scranton, and Franzen in their embrace of eco-nihilism. David Wallace-Wells and Dipesh Chakrabarty, for instance, have argued that it is not too late to take action. Yet in their different ways these authors end up as proponents of a new kind of climate denialism. The eco-nihilist denial that there is anything to be done is replaced by a denial of the class character of global warming.

In his 2019 bestseller The Uninhabitable Earth, Wallace-Wells explains in great detail how the world’s inhabitants will suffer on a warming planet. “It’s worse, much worse, than you think,” the book begins. Wallace-Wells wants a falsely universalized “us” to feel the panic of comprehension as the severity of the crisis settles in. This panic, he thinks, will spur “us” into action. But the problem he addresses—awareness that action is needed—is no longer the issue. What is needed is a politics, and here Wallace-Wells comes up lacking. Now is not the time, he argues, to hold anyone in particular responsible for our climate calamity: “The burden of responsibility is too great to be shouldered by a few, however comforting it is to think that all that is needed is for a few villains to fall.”12

For Wallace-Wells, ecological devastation has not been wrought upon the few by the many. Rather, “each of us imposes some suffering on our future selves every time we flip a switch, buy a plane ticket, or fail to vote.”13 Never mind that 1.2 billion people today have little to no access to electricity. Or that 80 percent of the world’s population has never flown. Or, most egregiously, that ExxonMobil executives already knew that their industry was destroying the planet in 1977 but chose to hide their findings and fund climate change–denying research because there was money to be made in killing future generations.14 To blame everyone equally in the face of such extreme inequality is to take the side of fossil capital. It denies rather than clarifies the obvious: the climate crisis is a space of class struggle.

Because Wallace-Wells does not see the classed character of climate breakdown he is on the wrong side again when it comes to suggestions about mitigating its effects. He admits that he doesn’t “have a firm perspective” on whether capitalism can solve the climate crisis and yet he expresses an “intuition”—a kind of liberal environmentalist spidey sense—that “we don’t need to abandon the prospect of economic growth to get a handle on climate change.”15

Like Wallace-Wells, Chakrabarty denies the true political stakes of climate breakdown. He begins by asking the right question: “If the rich could simply buy their way out of this crisis and only the poor suffered, why would the rich nations do anything about global warming unless the poor of the world (including the poor of the rich nations) were powerful enough to force them?” But he comes to the wrong conclusion. Chakrabarty reasons that since “such power on the part of the poor is clearly not in evidence” and since the rich nations are not “known for their altruism,” “a better case for rich nations and classes to act on climate change … is couched in terms of their enlightened self-interest.” He thinks the rich simply need to be persuaded that it’s in their interest to get behind efforts to address climate change. His argument has more in common with bourgeois political economist Adam Smith than it does with the fight for social and climate justice. Like Smith’s “invisible hand,” it assumes that the self-interest of the capitalist class can be harnessed for the common good, that the “natural laws” of market competition have benevolent consequences.

Such thinking underestimates how much money there is to be made in a warming world. Mining companies buy land in Greenland with the knowledge that melting ice will reveal new mineral and oil reserves.16 Private security firms prepare to defend wealthy clients from civil unrest caused by droughts, floods, and famines.17 Dutch engineering companies sell flood-management expertise and plans for floating cities.18 Wealthy investors buy vast swathes of farmland in the Global South in hope of cashing in when droughts make arable land scarce.19 Many millions will die from the effects of global warming and capitalists are counting on it.

Capital’s self-expanding logic is indifferent to death. This is capitalism’s history and present. Investors and conservative opinion leaders prioritizing the capitalist economy over public health is one example. The refusal of Amazon to provide basic cleaning of its warehouses and personal protective equipment to its workers is another. The “enlightened self-interest” of the capitalist class is a fantasy that masks an underlying acceptance of exploitation, dispossession, and imperialism. Fundamental change is achieved through force, through class struggle, and through the agency of the oppressed.

Progressive intellectuals are not the only ones who deny that the climate crisis is political. Extinction Rebellion (XR), one of today’s most prominent environmental movements, argues that climate science speaks for itself and that politics gets in the way of action. The movement thus calls for a “move beyond politics.”20 The result is a denial of politics and a denial of responsibility.

XR describes itself as an “international apolitical network using non-violent direct action to persuade governments to act justly on the Climate and Ecological Emergency.”21 As its cofounder, Roger Hallam, explains in his pamphlet Common Sense for the 21st Century, the movement adopts an “apolitical” position in the hope of transcending bourgeois parliamentarism and social-movement factionalism.22 Hallam hopes to shift the climate crisis from a political issue to a moral one. He describes governmental inaction on climate change not as the conscious and strategic political decision to put profit before people and planet, but as a “moral failure.” Similarly, he presents the fight for social and ecological justice not as part of a mass working class movement but in terms of individual moral feeling.23

To declare oneself “beyond politics” does not erase the reality of politics. In fact, one of the strange things about politics is that the more you try to go beyond it, the more caught up in it you are. This is a lesson that XR should have learned when critics exposed its blindness to the politics of race, disability, and class, but it didn’t.24 XR’s moralism defaults to a white petit-bourgeois liberalism that conforms perfectly to the dominant ideology of our times: politics is bad because it is divisive, because it asks us to choose sides, to name our comrades and our enemies. Most of all, politics is hard because it asks us to take and wield power, to be disciplined, focused, and clear-eyed about what we hope to achieve. It will always be easier—and no doubt more immediately gratifying—to cohere an apolitical movement around an ill-defined set of goals with no real enemies.25

The Political Climate

Few are persuaded by the denial of the political nature of climate change. Persistent mobilization by grassroots activists has placed climate clearly on the political agenda. Polls in the UK and the US indicate that voters recognize climate change as a matter of politics: it’s an issue that simultaneously divides and necessitates a political response. Moreover, as is clear to nearly everyone, the scale of the catastrophe requires a state response.

The current most compelling framework for such a response is the Green New Deal (GND). As the leading progressive state-based response from US Democrats, the UK’s Labour Party, the Spanish Socialist Party, and others, the GND will play a huge part in the climate struggle over the next few years. In contrast to the failed neoliberal attempt to address rising CO2 levels by creating a market for carbon credits, the GND puts forward a green Keynesianism that places public job creation and enhanced social welfare at the center of its decarbonization strategy.

According to John Bellamy Foster, the term “Green New Deal” was coined in a 2007 meeting “between Colin Hines, former head of Greenpeace’s International Economics unit, and Guardian economics editor Larry Elliott.”26 Hines’s term for an FDR-style state program was also used by New York Times columnist and corporate hack Thomas Friedman for an eco-modernist, technocratic green capitalism. Over the next few years, the UN Environment Development Program and the Green European Foundation published similar proposals for a mildly reformed green capitalism. More recently, a radicalized version has been pushed by groups like Commonwealth, which advocates for democratic ownership, and the Climate Justice Alliance, which fights for environmental justice for frontline communities. This new GND, which took shape as a grassroots strategy during Jill Stein’s Green Party presidential campaigns in the US, linked the response to the climate crisis to the imperative of responding to the social crisis. The Stein campaign highlighted the role of US imperialism in both: not only is the US military the largest institutional carbon emitter on the planet, and not only does US militarism destabilize and immiserate millions across the planet, but cutting the military budget could pay for new energy infrastructure and decrease emissions in one go. Demilitarization—defunding the military and the police—is essential to climate justice.

Bernie Sanders’s version of the GND includes Stein’s anti-imperialist proposals. It also, as Alyssa Batisstoni and Thea Riofrancos point out, promotes regenerative agriculture, prioritizes a just transition, treats energy as a public good, and holds the fossil fuel sector accountable for climate change.27 This last provision is worth considering in some detail. The section of Sanders’s GND statement titled “End the Greed of the Fossil Fuel Industry and Hold Them Accountable” has seventeen separate proposals. These include banning fracking and mountaintop-removal coal mining, banning imports and exports of fossil fuels, banning offshore drilling, ending fossil fuel extraction on public lands, ending fossil fuel subsidies, and ending new fossil fuel infrastructure permits. Additional measures raise taxes “on corporate polluters’ and investors’ fossil fuel income and wealth,” and raise and enforce EPA penalties on fossil fuel–generated pollution. They pledge to bring criminal and civil suits against the fossil fuel industry and make it pay for the damages it has caused.28 Altogether the proposals wage a fierce battle against big carbon, doing everything but nationalizing the industry.

Given the radical nature of the measures proposed to hold the fossil fuel industry accountable, why doesn’t Sanders go all the way and propose to nationalize the industry, dismantling or restructuring it in the service of clean energy? After all, the plan invites the combined fury of the entirety of the capitalist class, threatening their profits, stranding their assets, and undermining their stock valuations. The answer must be that Sanders needs the carbon sector to survive, at least for a while. His GND plan is built on a contradiction: it requires the continued existence of the corporations responsible for climate change because it wants to make those corporations pay for the response. If the corporations were nationalized, or if they collapsed too quickly, they wouldn’t be able to pay. This contradiction is profound, much more disturbing than the tension between class war and green growth. If the oil and gas sector pays for the collective response to the climate crisis, then it cannot be abolished. In effect, the GND ends up on the same side as disaster capitalism’s climate change profiteers. Green social democrats end up having to defend the very industry that is destroying the planet.

The UK Labour Party made its version of the Green New Deal, the “Green Industrial Revolution” (GIR), a central plank of its 2019 election manifesto.29 The policy is unquestionably the most radical piece of climate legislation the UK has seen from a major political party. It promises more than one million green jobs, nationalized and affordable energy and transport sectors, a major buildout of renewable energy infrastructure, a ban on fracking, and an end to all UK Export Finance support for fossil fuel projects. Corbyn’s Labour Party also promised to decarbonize the UK’s energy sector—but not the whole economy—by the end of the 2030s, a full decade before the UK Conservative Party has proposed to. Had Labour won the 2019 election these policies would have transformed the UK for the better.

Nevertheless, like its US counterpart, Labour’s GIR is an effort to square decarbonization and global climate justice with a nationalist project of growth and development predicated on an exploitative system of wealth and resource extraction from the Third World. Labour’s manifesto explains that it plans to fund the GIR through a greenwashed public financial sector and taxes on wealth and capital. This neo-Keynesian approach is less immediately contradictory than Sanders’s GND, but Labour also aims to fund decarbonization by becoming a world leader in green technology and the provision of green loan programs to the Third World, while exploiting the Third World for the raw materials—rare earth minerals, copper, lithium, and more—that Labour’s industrialized transition demands.30 As Cooperation Jackson’s Kali Akuno argues in a different context, this amounts to a kind of green imperialism.31 The plan is to profit from the global transition to a post-carbon economy by doing what the ecologically destructive capitalist core has always done: extract raw materials and wealth from the world’s periphery. Little has changed, it seems, since Frantz Fanon first wrote that “Europe is the creation of the Third World” six decades ago.

Many involved in the progressive wings of the Democratic and Labour Parties are aware of these contradictions. And yet they deny their political consequences. Like Roosevelt’s New Deal before them, the GND and the GIR try to forge a social compromise between the exploiters and the exploited, the polluters and the polluted. Rather than naming the climate crisis as a space of class struggle—and following through with the consequences of this diagnosis—these policies aim to smooth over the cracks that are appearing in capital’s edifice as we hurtle headfirst into a warming world. By masking the brutal, exploitative, and unsustainable logic of capital accumulation, both plans serve an ideological function. They promise those of us in the imperialist core that nothing essential has to change as long as we transition from fossil-fueled capitalism and fossil-fueled imperialism to a greener capitalism and a greener imperialism.32 Climate breakdown demands that relations between the capitalist core and the super-exploited periphery be radically transformed. If we want to avert further compounding disaster we must abolish this distinction entirely. “Green growth” won’t cut it.33 A “steady-state economy” won’t cut it. We need to break from capitalism. It really is ruin or revolution.

Seizing the Means, Seizing the State

The green neo-Keynesianism of the GND and GIR is a dead end, but it would be a mistake to conclude that there is nothing to learn from these plans. Thea Riofrancos calls such left conclusions a “politics of pure negation.”34 With this she has in mind views like those expressed by Jasper Bernes and Joshua Clover who have argued that the GND is a materially unrealizable distraction. These authors think the left should critique the GND and move on. But to what? Yes, to revolution—no disagreement from us. But to build what? And how? Here we agree with Riofrancos that fully dismissing the GND and GIR is “neither empirically sound nor politically strategic” even as we reject her proposed alternative of “critical support.”

For Riofrancos, a politics of pure negation is unhelpful because it mistakes the GND for a “prepackaged solution” to the climate crisis that one either accepts or rejects wholesale. She proposes that the plan is better thought of as an ever-changing “terrain of struggle” with “the potential to unleash desires and transform identities” and reasons that if the final shape of the GND is still to be decided, then to reject it is to cede important territory to fossil capital. As an alternative, she suggests that we “take our cue from social movements that adopt a stance of critical support, embracing the political opening afforded by the Green New Deal while at the same time contesting some of its specific elements, thus pushing up against and expanding the horizon of possibility.”35

“Critical support” for the GND is as unsatisfactory as a politics of “pure negation.” Like all democratic socialist strategy, it subordinates working class struggle to the task of electing progressive candidates. It gives up on the left’s revolutionary tradition to focus instead on the more “realistic” task of agitating for gradual leftward shifts in the Overton window. As with all political strategies, the efficacy of democratic socialism rests on the achievability of its aims. While Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour’s leader in 2015 and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s success in 2018 gave democratic socialism a boost, the Democratic National Committee’s opposition to Bernie Sanders and the 2019 UK election have shown the limits of mainstream parties’ tolerance for socialism. To think it possible to implement a progressive GND with the DNC that we have, the Supreme Court that we have, the House of Lords that we have, or the patterns of property and land ownership that we have—that is to say, with the capitalist state that we have—is to assume that the institutions of ruling class power can be used for mass benefit without removing the ruling class. Riofrancos proposes that “extra-parliamentary, disruptive action from below” should be combined with “creative experimentation with institutions and policies,” but surely by now—in the midst of compounding crises—we should be beyond experimenting with bourgeois institutions on bourgeois terms.

Riofrancos’s “critical support” excludes the option of building towards revolution. As her argument unfolds, it moves from defending the GND as an important site of struggle to arguing that it is the site of struggle. To question the GND’s electoralism is to make a choice for “resignation cloaked in realism,” to acquiesce to an endless “waiting for [the] ever-deferred moment of rupture.” The obvious but unspoken third option here, though, is to build toward the moment of “rupture,” or more concretely the seizure of power, outside of the Democratic or Labour Parties. No doubt this option remains unspoken because it is too “unrealistic,” too undemocratic, and too “authoritarian” for democratic socialists to countenance.36

Let’s look at this third option more closely. To build towards an eco-communist revolution, we need to avoid both a politics of pure negation and a politics of “critical affirmation.” As Marx argued, revolutions need dialectics. They need us to find what Fredric Jameson calls the “dialectical ambivalence” in capitalism. This means training ourselves to locate aspects of the present that point beyond themselves and towards the communist horizon. Lenin did precisely this after the outbreak of the First World War. Rather than joining with the majority of the socialist parties of the Second International in capitulating to imperialist war, and rather than wallowing in melancholia following the betrayal of so many of his German comrades as they voted for war credits, Lenin saw in the war an opportunity for revolutionary advance. Those interested in the emancipation of the working class needed to fight not for peace but for the dialectical conversion of nationalist war to civil war.37 The war, and the collapse of the Second International, was the opportunity for something new.

What would it mean to think dialectically about the GND? We think it would mean stripping the policy’s reformist content away from its revolutionary form. For decades environmental movements in the capitalist core have busied themselves fighting for local solutions to global problems: cooperatives, local currencies, urban agriculture, and ethical consumerism. As these experiments blossomed, the climate crisis continued unabated. More pipelines were built, more indigenous land was stolen, more fires raged, and more species flickered out of existence.

In their form the GND and GIR put localism aside. Both recognize that the climate crisis demands a state-led, centrally planned, and global response. They take for granted that we need a state to intervene on behalf of nature and workers against capital. The fact that the GND and GIR promise to do this is what makes capitalists fear them.38 Those who are excited about the promise of the GND—such as Riofrancos—have similarly turned towards the state as a terrain of struggle and a locus of power. Consciously or not, these movements have learned from the failures of Climate Camp, Occupy, and the Movement of Squares. It is not enough to suspend the normal running of things. Taking responsibility means taking power and organizing society in what Marx called the interests of “freely associated workers,” or more controversially, the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” The struggles to implement the GND and GIR tell us that environmentalists are increasingly aware of the need to seize the state—and the need to develop a fighting organization with the capacity to do so.

Against State Denialism

Ironically, at almost the precise moment that progressive movements have become conscious of the necessity of a climate response operating at the necessary scale, the Marxist left has taken a state-phobic turn. Consider “disaster communism.”39 Confronted with the choice between ruin or revolution, disaster communism opts for ruin as the path to revolution—without considering the form of association necessary to ensure that the revolution ushers in a more equal, just, and sustainable world rather than insulated groups struggling with each other over resources. In lieu of the revolutionary subject emphasized in the Marxist tradition, disaster communism turns to climate breakdown as the agent of history.

Drawing on Rebecca Solnit’s book A Paradise Built in Hell, a study of how practices of mutual aid and collectivity arise in the aftermath of crises, disaster communists argue that we do not need to seize the state because the state will be washed away, along with the capitalist system itself, as the full force of the climate crisis crashes down around us. While Solnit emphasizes the ephemerality of “disaster communities,” disaster communists ask how these communities might be sustained and even flourish well beyond the punctual point of a climatic disaster wrought by capitalism. Theirs is a vision of communism arising, triumphantly, from capital’s ashes. Vision may be too strong a term here: for the most part, disaster communism is a hope, a screen covering over the need for organization and planning at a scale that can produce a form of life suitable for billions of people and nonhuman species.

Responses to the Covid-19 pandemic illustrate the point. Even as mobilized volunteers and mutual aid can meet real needs by distributing meals, assisting neighbors, and coordinating webinars, they are inadequate to the most demanding tasks of developing and administering tests for the virus, securing hospital beds in intensive care units, producing and distributing respirators, and providing adequate protective equipment at the necessary scale. Mutual aid is inspiring, but it’s not enough—it can’t stop the hoarders and profiteers, pay hospital bills and unemployment insurance, release prisoners and detainees. It doesn’t scale, particularly when the prevailing logic comes from the market. That capital accumulation takes place through dispossession as well as exploitation brings home the real limit of mutual aid: poor and working people do not own the means of production and therefore production does not meet social needs.

Furthermore, in extreme capitalist countries like the US and the UK, social and political diversity means that many do not voluntarily comply with public health recommendations. Employers insist that employees come to work. Students spend spring break at the beach. Individuals approach their own situations in terms of exceptions, reasons why they don’t need to comply with directives. Orders from the state don’t eliminate all these exceptions. But they reduce them substantially, most significantly by preventing employers from requiring workers to put themselves at risk. Were the state used as an instrument of working class power, it would, at a minimum, guarantee that workers would continue to be paid, that the health and well-being of people would be the focus of government attention. The pandemic demonstrates a truth that the left’s responses to climate change have been slow to acknowledge: global problems require a centrally planned response with all the tools that are at the disposal of the state. Failing to seize hospitals, industry, banks, and logistical networks from the capitalist class results in needless death—and gives a green light to disaster capitalism.

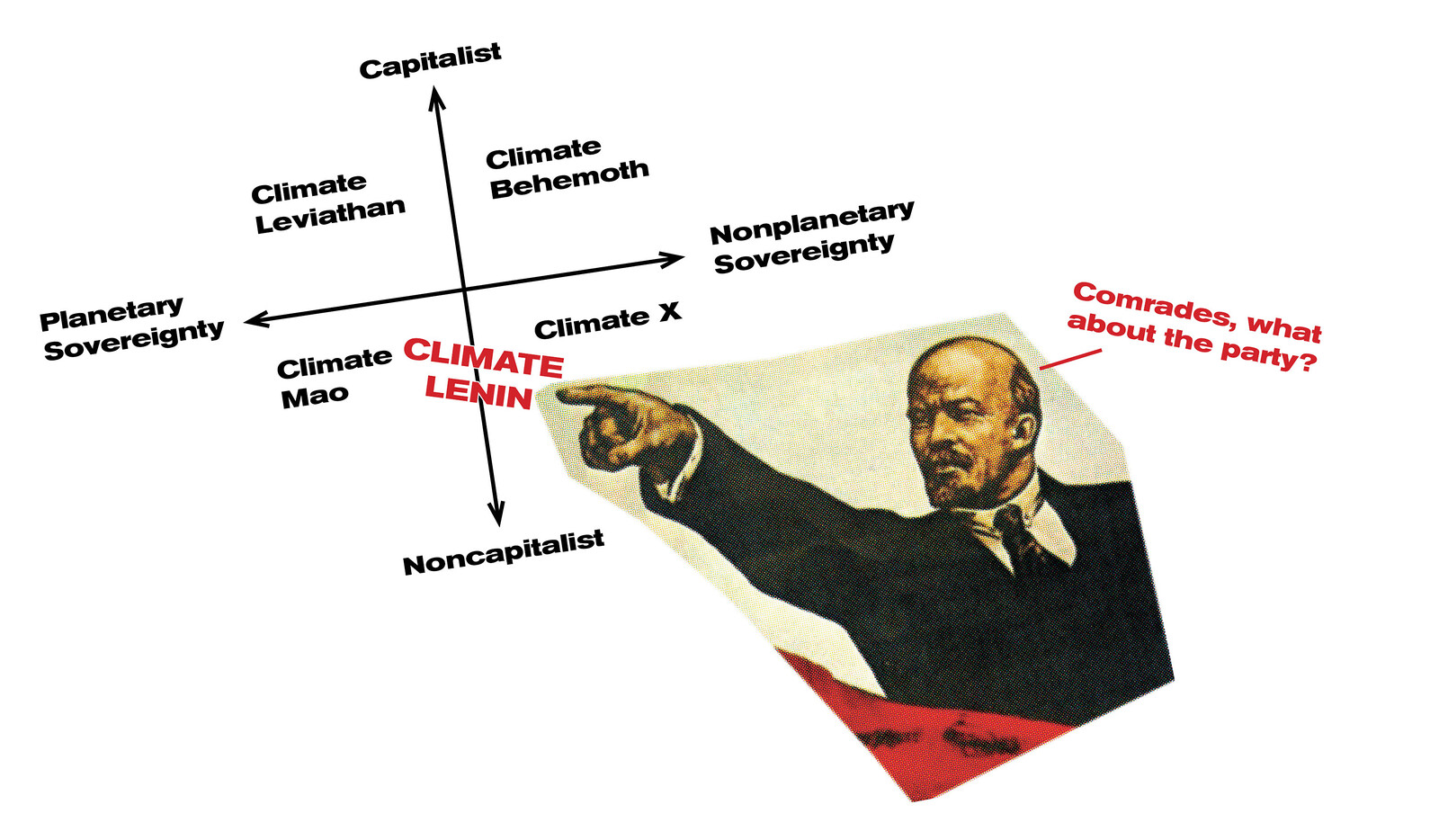

Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright’s 2018 book Climate Leviathan provides another state-phobic response to the climate crisis. Mann and Wainwright predict four possible resolutions to the climate crisis. The first is “Climate Leviathan.” This is a global sovereign power that would act in the interests of capitalist states and global capital to limit the effects of climate breakdown. This is effectively the scenario hoped for by Chakrabarty. The second is “Climate Behemoth.” Here, states cannot agree to constitute a global sovereign power and so the crisis is tackled by international capital in the interests of international capital. The third is “Climate Mao.” In this scenario a single authoritarian sovereign power, most likely China, leads global mitigation and adaptation efforts. Finally, their fourth and preferred scenario is “Climate X.” This would be a so-far-nonexistent social movement that struggles to resolve the crisis in a way that is simultaneously anti-capitalist and anti-sovereign.

Alyssa Battistoni and Patrick Bigger have already written compelling Marxist critiques of Climate Leviathan.40 We don’t need to rehearse them here. We note, however, that responses to the Covid-19 pandemic have resembled Climate Behemoth and Climate Mao. While the US, UK, and EU have been slow to use state power to coordinate either within or among the themselves, instead following the dictates and interests of capital in their structuring of economic responses to the pandemic, China has modeled both rigorous state action with respect to quarantines and international leadership with respect to provision of medical aid. What’s important for our argument here is that Mann and Wainwright’s state denialism prevents them from conceiving the state as a form for the collective power of working people, an instrument through which we remake the economy in the service of human and nonhuman life.

Jasper Bernes offers a third state-phobic Marxist response to the climate crisis. A proponent of communization theory, Bernes argues that communism means “the immediate abolition of money and wages, of state power, and of administrative centralization.”41 Absent something like a state, how is a just response to the climate crisis even possible? Should we assume that it will spontaneously emerge as a result of disparate local disaster communisms? Should we assume that access to food, water, living space, and capacities for self-defense will be equally distributed, that by some miracle the immediate abolition of money and wages will leave everyone in the same position? The pandemic gives us insight into the inability of the communization approach to respond to catastrophe: when millions who have been dependent on the wage are without it, they require centralized state power to seize the means of production and distribution and administer both on the scale necessary to meet social needs. The issue isn’t the power of the state. It’s the class wielding state power.

Climate Lenin

Lenin recognized the difference between confiscation and socialization, or, more in keeping with the terms here, between abolition and communism. The latter requires creative, collective cooperation, which has to be organized. Through the reorganization of the modes and relations of production and reproduction, the many come to exercise control over their lives and work. Neither revolution nor communism occurs in a single moment. For communists, revolution is the process of building communism. The negation of prior practices, assumptions, and institutions doesn’t happen overnight. Acknowledging the “long haul” is not to capitulate to capitalism or social democracy. It is how we refuse to capitulate to capitalism and democracy and accept the complexity of the task of building free societies and the revolutionary organizations adequate to that task.

One of the lessons Lenin took from the experience of the Paris Commune was the revolutionary role of the state. He applied this lesson to the setting in which the Bolsheviks found themselves:

This apparatus must not, and should not, be smashed. It must be wrested from the control of the capitalists; the capitalists and the wires they pull must be cut off, lopped off, chopped away from this apparatus; it must be subordinated to the proletarian Soviets; it must be expanded, made more comprehensive, and nation-wide. And this can be done by utilising the achievements already made by large-scale capitalism (in the same way as the proletarian revolution can, in general, reach its goal only by utilising these achievements).42

The state is a ready-made apparatus for responding to the climate crisis. It can operate at the scales necessary to develop and implement plans for reorganizing agriculture, transportation, housing, and production. It has the capacity to transform the energy sector. It is backed by a standing army. What if all that power were channeled by the many against the few on behalf of a just response to the climate crisis?

During the Covid-19 pandemic, multiple voices have called on the state to take control of hospitals and industries, to build field units, supply necessary equipment, and provide economic relief. State response has been uneven, typically coupling enormous benefits to corporations with minimal benefits to working people. Even worse, repressive regimes such as those in Hungary and the US have seized the opportunity to enact anti-trans, anti-abortion, and anti-environmental measures. Again, our situation is one of revolution or ruin.

As Ted Nordhaus argues in a pro-capitalist takedown of the contemporary left, the progressive response to climate change has failed because of the incoherence between its diagnosis and its solution.43 The left sees that capitalism is responsible for climate change. It recognizes the urgency of the situation. But instead of building its capacity to seize the state, it advocates small-scale, local, decentralized solutions and more protests and democracy. If we really are on the verge of catastrophe, shouldn’t we building a revolutionary party able to respond to the disaster and push forward an egalitarian alternative?

The left has offered moralism when it needs to offer organization. Consider the contrast between the widely popular Fridays for the Future protests and the mass strikes in France and India. The former attempt moral persuasion. The latter assert proletarian power as they interrupt capital’s circulation and stand up against capital’s state. What if electrical workers all over the world followed the lead of their French comrades and turned off the lights? What if all transport workers refused to drive or fly all vehicles that weren’t zero-emission? What if the global working class emulated the 250 million Indians who brought their country to a halt with their January 8, 2020 general strike? Such mass working class action creates the space for further radicalization, further organization, further conviction that we have the capacity to bring about a radical transformation of the global economy. Organization, not moralism, gives us the power.

Nordhaus pinpoints the cause of the left’s incoherence: its rejection of centralized, top-down power. Climate Leninism, however, doesn’t fall for this tired spatial metaphor. When the state is seized by a revolutionary party, it is turned bottom-up. Grappling with the challenge of working this out in practice occupied Lenin until the end of his life. Getting local soviets or worker’s councils functioning is a challenge. In a complex federated system like the US, there are already elaborate local, county-wide, state, and national governmental offices. Lenin himself was particularly enamored of the post office and libraries, seeing both as models for socialist accounting and distribution. Our problem today is not excessive centralization. After forty years of neoliberalism, it is disorganization, unaccountability, ongoing exploitation, and widespread accumulation by dispossession. We need a politics adequate to this context, a militant, disciplined, communist politics that doesn’t flinch from the enormity of the challenge, nor the coordination at scale required to address it.

We know that this is a tall order. We know that the forces of fossil capital and social democracy stand in our way. But to do anything less than build towards an international revolution today would be ruinous. As dire as both the coronavirus and climate crises are—and we really have seen nothing yet—we need to exercise some dialectical ambivalence. Global capital sees these crises as an opportunity to entrench its power, to break into new markets, to extract more wealth. Social democracy sees the crises as a chance to strike an impossible social compromise between capital and workers. We need to see these crises as both social and ecological catastrophes of unprecedented proportions and as an opportunity to end exploitation, oppression, imperialism, and inequality. We need to see this moment from the perspective of the revolutionary party that we must build as climate Leninists.

Mallory Hughes, “The Koala Population Faces an Immediate Threat of Extinction After the Australia Bushfires, New Report Finds,” CNN, March 5, 2020 →.

Dr. Paul Griffin, The Carbon Majors Database: CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017 →.

Kendra Pierre-Louis, “Ocean Warming Is Accelerating Faster Than Thought, New Research Finds,” New York Times, January 10, 2019 →.

Alan Buis, “A Degree of Concern: Why Global Temperatures Matter,” climate.nasa.gov, June 19, 2019 →.

Jason Samenow, “Debunking the Claim ‘They’ Changed ‘Global Warming’ to ‘Climate Change’ Because Warming Stopped,” Washington Post, January 29, 2018 →.

“World Faces ‘Climate Apartheid’ Risk, 120 More Million in Poverty: UN Expert,” UN News, June 25, 2019 →.

Karl Marx, “On the Irish Question.” Available at marxists.org →.

Molly Moorhead, “Obama Says New Miles of Pipeline Could Stretch Around the Earth,” Politifact, April 23, 2012 →.

Jem Bendell, “Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy,” July 27, 2018 →.

Roy Scranton, “Learning How to Die in the Anthropocene,” The Stone (blog), New York Times, November 10, 2013 →. Scranton expanded this article into a book: Learning to Die in the Anthropocene (City Lights Publishers, 2015).

Jonathan Franzen, “What If We Stopped Pretending?” The New Yorker, September 8, 2019 →.

David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming (Tim Duggan Books, 2019), 30.

Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth, 30–31.

Bill McKibben, “What Exxon Knew About Climate Change,” The New Yorker, September 18, 2015 →.

Ian Tucker, “David Wallace-Wells: ‘There are many cases of climate hypocrisy,’” The Guardian, August 25, 2019 →.

Brad Plumer, “Meet the Companies That Are Trying to Profit from Global Warming,” Vox, September 4, 2015 →.

Noah Gallagher Shannon, “Climate Chaos Is Coming—and the Pinkertons Are Ready,” New York Times Magazine, April 10, 2019 →.

Plumer, “Meet the Companies.”

Brad Plumer, “Why Wall Street Investors and Chinese Firms Are Buying Farmland All Over the World,” Vox, May 15, 2015 →.

Extinction Rebellion, “Our Demands” →.

Extinction Rebellion, “Our Demands.”

The pamphlet has since been turned into a book →.

Roger Hallam, “We Are Engaged in the Murder of the World’s Children,” interview by Laura Backes and Raphael Thelen, Der Spiegel, November 22, 2019 →.

Kuba Shand-Baptiste, “Extinction Rebellion’s Hapless Stance on Class and Race Is a Depressing Block to Its Climate Justice Goal,” Independent, October 15, 2019 →.

Extinction Rebellion, “Our Demands.”

John Bellamy Foster, “On Fire This Time,” Monthly Review, November 1, 2019 →.

Alyssa Battistoni and Thea Riofrancos, “Bernie Sanders’s Green New Deal Is a Climate Plan for the Many, Not the Few,” Jacobin, August 23, 2019 →.

See →.

See →.

Jasper Bernes, “Between the Devil and the Green New Deal, April 25, 2019,” Commune, April 25, 2019 →.

Kali Akuno, “We Have To Make Sure the ‘Green New Deal’ Doesn’t Become Green Capitalism,” interview by Sarah Lazare, In These Times, December 12, 2018 →.

Max Ajl, “How Much Will the US Way of Life© Have to Change?” Uneven Earth, June 10, 2019 →.

United Nations Environment Programme, A Global Green New Deal: Policy Brief, March 2009 →.

Thea Riofrancos, “Plan, Mood, Battlefield – Reflections on the Green New Deal,” Viewpoint, May 16, 2019 →.

Riofrancos, “Plan, Mood, Battlefield.”

Frederick Engels, “On Authority.” Available at marxists.org →.

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Reminiscences of Lenin, translated by Bernard Isaacs (Haymarket Books, 1960), 293.

Kai Heron, “Capitalists Fear the Green New Deal—and For Good Reason,” ROAR, May 8, 2019 →.

Out of the Woods, “Disaster Communism,” Libcom, May 2014 →.

Jasper Bernes, “The Belly of the Revolution,” in Materialism and the Critique of Energy, ed. Brent Ryan Bellamy and Jeff Diamanti (MCM’, 2018), 358 →.

Vladimir Lenin, “Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power?” Available at marxists.org →.

Ted Nordhaus, “The Empty Radicalism of the Climate Apocalypse,” Issues 35, no. 4 (Summer 2019) →.