There is a sharp contrast between, on the one hand, the often blunt commodification of art (and the processes of branding and generating wealth connected with it), and, on the other, the extremely heterogeneous, fragile practice of creating art. In fact, a good part of what makes an artist succumb to blunt commodification is the sheer anxiety caused by that heterogeneous fragility. Producing easily marketable, no-questions-asked work can offer a (deceptive) security no longer provided by classical avant-garde panache. There is no clearly distinguishable movement in sight that would lead out of this apparent deadlock. Given this, what are the options, the cracks of light in the otherwise uniformly dark, dystopian vision of poor, anxious artists doing irrelevant work for the rich? The answer to this question, as I will argue, is that today there is a kind of movement whose point is not to be clearly distinguishable, not to be “pure” anymore, not to allow itself to be historicized that way.

But before making that argument, it’s necessary to understand what the last clearly distinguishable movements were, and why there now are none. The last period in visual arts that produced such movements was the 1960s: Pop Art, Minimal Art, and Conceptual Art. These movements were “distinguishable” because they were defined by a small set of methodological operations that could be identified as innovative in comparison to other achievements in art, whether earlier or contemporaneous. In other words, they were avant-gardes. Still, defining the “essence” and “newness” of these movements, or deciding whose work belongs clearly enough to any of them, has remained an often ideologically charged issue for many artists, critics, and scholars alike. And many of them have abandoned the very idea of a “movement.” Usually they have done so in the name of either idiosyncrasy or the genius of the individual artist. Or they have done so, on the contrary, in the name of a more totalized idea of creative collectivity that supposedly “transcends” the limits of an “-ism” or mere “style.”

But whether or not you’re against the idea of movements no longer seems to be the problem. From the 1970s on, it has been difficult or next to impossible to clearly identify them in the first place. Everything became “neo-this” or “post-that,” or a pronounced crossbreed between previous movements. Around the early 1980s in Europe and the U.S., “neo-expressionist” painting set out to reinvigorate older ideas of artistic intensity and immediacy, but—to generalize—remained less about changing the way you painted than about changing the way you presented yourself doing so. The method—paint fast, wittily—was considered a direct outpouring of a (usually masculine) rebellious attitude. At around the same time, neo-conceptual or appropriation artists such as Richard Prince or Sherrie Levine built on the achievements of Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, on the ideas of the readymade, of appropriating existing cultural artifacts as art, and of making intelligent artistic use of reproduction technologies. But regardless of their qualities as individual artists, the question remains whether they truly advanced or departed from these pioneers with that methodology. The same could be said of artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija or Philippe Parreno who, from the mid 1990s on, have been associated with the catch phrase “Relational Aesthetics”: did their artistic evocations of social situations (whether cooking in a gallery or buying the rights to a Japanese anime character), their deconstructions of the categories of “artwork” and “exhibition,” really move beyond the achievements of the 1960s? After all, already in 1969 a conceptual artist, for example, offered a reward of $1,100 for information leading to the arrest of a bank robber wanted by the FBI (Douglas Huebler, Duration Piece No. 15, Global). In the contemporary Chinese context, similar questions can probably be asked about the “Cynical Realism,” “Political Pop,” or “Gaudy Art” styles of the 1990s: besides their aspirations to subvert through satirical, ironical, or grotesque figurative representation and their indisputable pioneering importance for the establishment of a new art scene, what did they really achieve methodologically in comparison to earlier movements?

In any case, rather than evoking the sense (or illusion?) of something radically new, these post- and neo- or cross-breed-movements, for better or worse, all seemed to be about re-investigating the heritage of previous movements (if seen generously), or about devouring their corpses (if seen nihilistically). Or is that all a retroactive illusion? Were the 1960s movements, which were equally concerned with historical predecessors, maybe more clever in concealing that fact? Were the postwar movements, as theoreticians such as German literary critic Peter Bürger have argued, merely recycling the early twentieth-century avant-gardes?1 And what does this mean for ideas of shock, radicality, and criticality? And can we still meaningfully categorize art in this way today?

Before we can explore all of these questions further, there are two points that need to be clarified. The first concerns the three aforementioned 1960s movements: we need to understand how exactly it became possible to give each a simple, singular name: Pop, Minimal, Concept. What does that tell us about their nature and continuing influence? The second point is that the seeming disappearance of clearly distinguishable movements is not at all exclusive to visual art, as similar developments can be discerned in other realms such as music, philosophy, and politics. In other words, a more fundamental sea change seems to be at work.

Pop/Minimal/Concept

So what is it that made Pop, Minimal, and Concept such appealing one-name signifiers? And why is it that we can no longer come up with anything as succinct and to the point in “labeling” broader developments in art? There is not enough space here to develop a full history of these terms, much less discuss the full range of artists and movements associated with them. So in order to answer this question, it’s worth examining the meanings of these one-name labels as such, and what those meanings might tell us about what decisive factors distinguish an artistic movement.

The term “Pop Art” was invented in Britain in the mid 1950s. It was first used in conversation between members of the Independent Group: a number of artists, architects, writers, and critics who held meetings at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, seeking to challenge prevailing notions of modern art. The artist Eduardo Paolozzi, a Scottish-born son of Italian immigrants, at the first meeting in 1952, showed a series of collages composed mostly of found elements from American mass culture. One of them included the word “pop,” placed on a cloud emerging from a revolver, followed by an exclamation mark, cut out of a comic strip and collaged onto the cover of a magazine of erotic pulp stories called “Intimate Confessions.” So the word is onomatopoetic: it emulates the sound of a shot, or of a bubble bursting—pop! The sound of a sudden release of energy, light rather than heavy. The association of this energy with light entertainment is made even clearer in the other seminal collage from the early days of Pop Art: Richard Hamilton’s Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956). The collaged living room scene, similar to Paolozzi’s work, ironically alludes to romance and sex in a slapstick collision of clichés of masculinity and femininity. The bodybuilder placed in the middle holds what looks like a tennis racket, but is in fact a huge lollipop inscribed with the capital letters “POP” — which also happens to be the colloquialism for “lollypop.” This English term dates back to the eighteenthcentury, and initially referred to soft candy. It may have derived from “lolly” (tongue) and “pop” (slap).2 The first references to the lollipop as hard candy on a stick dates to the early twentieth century, when it became possible to mass-produce them.3 The term “soda pop,” for sweet soft drinks such as Coca-Cola, also presumably stems from this period—probably earning its name from the sound one hears when opening the bottle. Either way, what we have here is a conversion between light-hearted pleasure and craving desire: the connection between innocent sweetness and bluntly sexual connotations, which the works by both Paolozzi and Hamilton do more than just allude to. In the latter’s case, the lollipop, through its placement at the crotch of the muscular man, becomes a grotesquely bulbous phallus. The origins of Dada and Surrealism are here, but so is the new teenage culture of rock ’n’ roll that moves and shakes and sexualizes the bodies of a much broader populace.

The art critic Lawrence Alloway is often credited with having first come up with the term “Pop Art.” But he identified the movement without using the term. In his 1958 essay “The Arts and the Mass Media,” though he speaks of “mass popular art,” he does not address fine arts to any great extent.4 Rather, he argues much more broadly for the validity of popular culture itself, thus paving the way for this new art. In any case, here we have the more obvious, technical meaning of the word “pop”—as an abbreviation, simply, for popular: the culture of, and for, the many. But the onomatopoetic meaning of “pop!”—the sound of a conversion between light-hearted innocence and almost violent desire—permeates this technical meaning. This culture of and for the many is not merely defined by quantity but also by a particular quality, a kind of instantly inflating and deflating delight, like the refreshing sound of a bottle opening, or the silly “pop” of a deflating balloon, a quality for which it is praised or scorned, sometimes both at once—Pop!

The Pop artists transferred this instantaneousness into the realm of art, turning slight delight into eternalized epiphany. But this “transfiguration of the commonplace,” to use Arthur Danto’s phrase, does not turn Pop artists into priests of this transfiguration.5 Rather, they are just exceptional, or exemplary, in singling out the occurrences of this delight-as-epiphany. This decidedly marks the shift from the first British Pop art of Paolozzi and Hamilton, still in the tradition of the Dada/Surrealist collage (as Peter Bürger had suspected), and that of Andy Warhol’s substitution of collage with serialization. In doing this, Warhol is not just applying one more clever idea; he erases the “artistic” exemplification of composition still present in collage to expose the artist as simply, or merely, an exemplary or substitutional consumer—someone who makes a picture choice. At the same time, he also erases “comment”: while a collage still suggests a meaning and an opinion, serialization—by leaving elements to collide suggestively—dissolves meaning and opinion into ambiguity. One could suspect that Warhol celebrates the Coca-Cola bottle or Marilyn Monroe by serializing their image in silkscreen, but does that apply to the newspaper image of an electric chair as well? In either case, the mechanistic approach is the point. The sudden inflating/deflating “pop” sound represents our passiveness in the moment we are caught unaware vis-à-vis the commodity: our opinion or choice in regard to these images (a choice often structurally preconditioned by what is made available in our society in the first place) is no more than that of a consumer, a reader, a viewer. But even if we do not really like them, we have to admit that they affect us. At this point, the artist is no longer the producer, as opposed to the viewer, but the exemplary viewer and the exemplary consumer—a particular kind of consumer: the “classical” consumer who has a relatively stable set of choices and references that are part of his social identity (I’ll return below to the definition of the “consumer”). If Pop celebrates anything, it is not commodities as such, but this totalized identification of the artist with the role of the spectator/consumer confronted with commodities.

Minimal

When Minimal art first emerged in the U.S., it seemed to be the antidote to all of this. No visual icons of the commodity world, just plain surfaces, reduced geometries. The term was arguably first used by the critic Richard Wollheim in an essay entitled “Minimal Art,” published in 1965.6 But it took years for it to catch on. Other terms such as Rejective art, ABC art, Specific Objects, Reductivism, and Primary Structures were launched. Only the last two, like “Minimal,” place the emphasis on simplification. “Rejective” emphasizes the departure from any kind of comforting “illusionist space,” story, or allegory in this kind of work; “ABC” its steady, simplistic seriality; and “specific object” its departure from the traditional categories of painting and sculpture.

But why did “Minimal Art” catch on? First of all, because it resonated with phenomena in other disciplines that seemed motivated by similar concerns—“minimalism” was something happening in music and dance, and arguably in film and literature, as well. What these movements share according to that view, however, is not merely an ideal of reductive form, but also a methodology of allowing things to stand or speak for themselves in an unpretentious, matter-of-fact way, that is, without the claim of a grand genius mind purveying them; without the display of handicraft; replacing lyrical or dramatic movement with serial movement; and maybe most importantly: providing a structure in which production and reception can interact. In the serial music of someone like Terry Riley, the performers often have more to do than just “interpret”; or the “actual” performing is done with a recording, while listeners have to possibly be more acutely active to immerse themselves in the space-time continuum of the music. But it’s also apparent in the idea most notably put forth by the minimal artist Robert Morris that the crucial point of minimal art is to establish a spatial relation between viewer and object, heightening the viewer’s self-awareness.7 An entire discussion has centered on the value of this emphasis on the viewer-work relation as opposed to qualities supposedly intrinsic to the work itself. But that discussion of evaluation aside, there is a structural kernel to all these aspects of minimal art. Pop art freeze-frames what consumers of popular culture experience into an iconic abstraction; minimal art, on the contrary, establishes simple structures that are like model scenarios for how aesthetic experience occurs in the first place. This happens almost literally in the sense of what Jacques Rancière calls the “distribution of the sensible”: establishing a form or manner in which something can appear, or “lend itself to participation.”8 Pop art hypostatized the receptive realm of consumption, while minimal art hypostatized the transitory realm of distribution or circulation—the realm where relations between production and consumption, object and viewer are negotiated. To substantialize or eternalize such a relational realm seems a contradiction in terms, but it’s not: what minimal artists offer in the way of viewer participation is an exemplary, simplified, model case. Its “minimal” quality is what makes its status as a model case apparent.

Concept

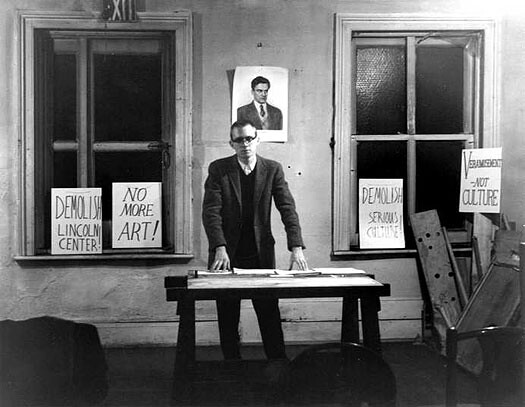

The term “Concept Art” was arguably first used by Henry Flynt, a writer and musician loosely associated with the Fluxus movement. In 1961 he wrote that the material of this kind of art consists of “concepts,” just as sound is the material of music.9 But it probably wasn’t until around 1968 that the term “Conceptual art” had fully established itself. Famously, Sol LeWitt stated: “the idea is the machine that makes the art.”10

2. The piece may be fabricated.

3. The piece need not be built.

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.11

Conceptual art in this sense mimics what an industrial designer or engineer might do: they design a brilliant new car, and even if the company decides not to build it, or no one wants to buy it, the design has come into existence and might have an influence on other designers and engineers. Of course this comparison is a little unfair, because the point of Conceptual art is precisely to take the utilization of ideas towards a sellable “product”—whether a shelf or a car—out of the equation. The idea itself is what is supposed to count.

Many conceptual artists would read the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, attracted to the way he combined clearheaded analysis of language and logic with a playful, deadpan style of writing. A good example—though not by an artist whose work is “purely” conceptual—is Bruce Nauman’s adaption of a phrase from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: he cast the sentence “A Rose has no Teeth” in lead, like a memorial plaque, and fixed it to a tree in a park (1966); later, he made copies in plastic and sent them to people in the mail. Wittgenstein had used the sentence in a comparison with the sentence “A baby has no teeth”—the problem he was concerned with being that grammar alone can’t distinguish plausible from implausible statements. Nauman’s reaction complicates the matter by casting an absurd-seeming sentence in lead, as if a poetics could emerge that suddenly highlights the actual profundity of the sentence “a rose has no teeth.” It’s as if Nauman were saying: what seems like a faulty design—an absurd sentence—can actually be turned into something interesting. The conceptual artists, on the idea level, turned nothing into something; and on the physical level, turned something into nothing (even Nauman’s lead plaque would eventually be overgrown by the tree).

The conceptual artist—whether concerned about art alone, or about the social and political sphere as well—impersonated the unashamedly absurd producer: a figure that is half-smart engineer, half-eccentric dilettante. In any case, emphasis is placed on highlighting the idea as anticipating—and prior to—any physical manifestation, the circulation and reception of a work. LeWitt’s “the idea is the machine that makes the art” in this sense also marks the heyday of industrialization, the devaluation of handicraft, and the dawning of an era in which indeed ideas—or at least information—are the “means of production” rather than actual machines. This can obviously lead to all kinds of suspicions: was conceptual art merely celebrating the new capitalist culture, the fetish of information and communication technology, the de-subjectivation of production and administration? I think these suspicions are beside the point as long as they generalize about the whole movement—because ultimately the problem is not that you produce but what you produce; not that you have an idea, but what kind of idea.

Production, Distribution, Consumption

But in any case, in my own admittedly schematic characterization, these three movements of the 1960s captured the basic economic triad of production, distribution, and consumption. Conceptual art is about the production of ideas that in turn produce the art; Pop art is an artistic exploration of the standards of the contemporary spectator’s experience; and minimal art is about structural parameters of space, materiality, geometry, and so on, that form the conditions under which aesthetic experiences that might lead to ideas can occur. Distribution or circulation are the realms in which production is both engendered in the first place (the means of production needs to be distributed before production can take place), and negotiated and compartmentalized in regard to consumption or reception. My argument however is not that these three artistic movements were simply illustrating the three basic aspects of the socioeconomic reproduction of society. Rather, I’m arguing that they are a seismic detector for a point in time when these realms became intermingled more radically than ever before.

It was already hard enough to distinguish production, distribution, and consumption from one another, since each reflects certain aspects of the other two. Any production is also a kind of consumption (for example, of resources), and consumption is also a kind of production (because without use the product is not “completed”); and distribution or circulation produce and consume simultaneously as well. Still, on a common-sense level, we sort of know the approximate difference. Yet in the age of the Internet, of financial markets so complex that the players themselves don’t fully understand its mechanisms, and of thoroughly global economic interdependence, it has become almost impossible to keep them apart. Information circulates so quickly, at such a high rate, and in such quantities that to sort it all out becomes a kind of production process in itself. The fusion of production and consumption has been heralded many times, by accentuating the classical way in which any production is a consumption of sorts, and consumption is always also a way of producing. But consumers of social networking Web sites such as Facebook are actually producing something beyond the mere completion or re-contextualization of a product given to them. And distribution or circulation is the very tool of that production. Whether this production is considered beneficial or not depends on many factors that need to be evaluated, which is not my concern here. Rather, I’m concerned with the effects this essentially technological and economic development has on the idea of distinguishable movements.

Classical avant-gardes were about generations in quarrel: Pop art, Minimal, and Conceptual art were not least rejections of the earlier Abstract Expressionism. But today, the idea of generations succeeding each other becomes blurred; as soon as you are willing to enter the circulation, it is possible to re-launch. Avant-gardes, in an odd way, were dependent on information, but also on a lack of information: a kind of productive ignorance of the contradiction of their rejections of previous generations, for example. This has become harder and harder: the more these contradictions have been discussed, the more it has become impossible to make the same “productive” mistakes again.

So are we dealing here with a kind of “saturation” of the idea that art could progress? A kind of historic accumulation of already-achieved expansions and reinventions of what art could be, leaving us feeling stranded amidst the flotsam of these previous achievements piling up in the museums, the libraries, and on the Internet? Evidence that this might be the case comes courtesy of the observation that this experience is not exclusive to art. In pop music, the last “explosions” of new styles were punk in the 1970s and hip-hop and techno in the 1980s; since then, a myriad of styles have been circulating, but none has had a comparable impact. In philosophy, the age of schools seems to be over, too; since the death of Jacques Derrida in 2004, all of the influential movements seem actually to be hybrids of earlier movements, even if they ironically argue for purity and against hybridity, and so on.

But is this really a problem? It is insofar as we demand that art (or philosophy, or pop music) completely re-invent itself once more. The thing is that this re-invention has become seemingly impossible because all these previous re-inventions were built on the possibility of expansion, and once the globe has been saturated with expansion, the only way forward seems to be to shrink backwards.

But we shouldn’t forget the well-known allegation against modernism, that it hypostatizes progress and invention, and thus perpetuates the capitalist ideology of newness. The allegation against postmodernism in turn is that it hypostatizes eclecticism and heterogeneity, late capitalism’s ideology of pick-‘n’-mix consumerism. I think both these allegations are hampered, if not outright wrong.

As for the allegation against modernism: the allegation erases a crucial difference between mere novelty and actual innovation that holds true both for the avant-gardes and for capitalism. You might hate capitalism, its cold mechanical production of success and annihilation, but you can’t ignore that in its history there have been innovations that exceeded, sometimes excessively, its own logic—one could for example argue that the Marxist tradition is a kind of critique that capitalism inevitably had to produce; or think, again, of the Internet, which on the one hand is a brilliant marketing device, but is at the same time a brilliant means of sabotaging that very marketing, if necessary. As Boris Groys has argued, “newness” is the negotiation of the division between what is considered profane and what is considered valuable.12

A similar thing can be said about art movements: at face value, they might “just” be about a stylistic innovation; but in fact they can foster “real” structural innovation, sometimes almost as a collateral effect. Think of how conceptual art has changed the way art is made; the “style” of, for example, writing up propositions with a typewriter may seem dated now, but nevertheless the conceptual methodology remains silently present in a great deal of art made today.

Just as method is not merely style, idea is not merely novelty. But how do we detect the difference? For a true idea in the “classic sense” to emerge, there are usually two contradictory telltale signs: it is met with rage and rejection, or it is completely ignored. In terms of European science, one could think of Giordano Bruno, who argued that the universe is endless and the stars we see are all distant suns. We know today that he was completely right, but in 1600 he was burned at the stake by the Church in Rome. In modern art, just to take two obvious examples: the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring in 1913 caused a riot, and the first presentation of Marcel Duchamp’s The Fountain (1917), the famous urinal as readymade, went completely unnoticed—people simply didn’t perceive it as a work of art.

Innovative concepts today are still met with rejection and ignorance, or a mixture of both. But usually the information is too readily available and there are too many players for things not to find an audience—the most outrageous or unthinkable things will be accepted even if only by a relatively small group, and in this sense, rage and rejection have been replaced by a kind of generalized indifference.

But should that indifference be held against art? Should art try to violently break through indifference by again provoking rage and rejection? Some artists in recent years have tried to do so, usually by way of breaking age-old taboos such as the peace of the dead, or cannibalism. I can think of two obvious Chinese examples: Zhu Yu, who allegedly ate a fetus (Eating People, 2000), and Xiao Yu, who exhibited the head of a dead fetus (Ruan, 2002). But things that shock can, instead of being avant-garde, be utterly conventional: in the sense that they do nothing but provoke shock based on the existing moral or juridical structure. Meanwhile, things that are applauded might be so for the wrong reasons—not for their innovative kernel but for their conventional shell. To answer the question of whether indifference should be held against art: I don’t think so. The value of art is not defined by immediate reaction, its true achievement may only be realized much later, in hindsight. So the tell-tale signs of a “new” idea—that it is met with rejection, ignorance, or both—don’t really work in a global environment of mass-media saturation. Boris Groys was right in arguing that acceptance of innovation depends on cultural archiving—one can only distinguish and appreciate the new in relation to the old.13 But what if that archive becomes so vast that it can’t be held in check, if it extends beyond any single human being’s capacity? Art has grown exponentially both through time and around the globe. Artistic innovation, it seems, can only be taken forward if it’s not so much about finding that one tiny thing that hasn’t entered the archive of cultural knowledge yet (the fetus meal, for instance), but about finding an innovative way of making use of that archive, or of settling into its cracks and uncharted assets. Innovation for a long time probably relied as much on information as it did on ignorance, or rather the luck of overlooking the right things. It’s become rather hard not to be relatively well-informed in a field when, via the Internet and growing archives, almost everything is available at hand.

Just as mere stylistic novelty needs to be distinguished from true structural innovation in the modernist conception, so with postmodernism does true heterogeneity needs to be distinguished from faux heterogeneity. Until quite recently, we could to some extent trust intuition: we knew the difference between a merely folkloristic, superficial demonstration of eclectic pastiche or multicultural harmony, and an actual cross-fertilization of different strands of cultural tradition. It becomes apparent in gesture, in the details of pronunciation, in the actual knowledge. The Internet, however, has changed this. Just as much as it blurs the line between the “now” of novelty and newness and the infinite depth of history and archive, it also blurs the line between fake heterogeneity and true heterogeneity. It has made it possible to produce atomized mutant hybrids between the two: people who are great enough fans will be able to find film footage and sound recordings and images and scholarly discussion of virtually anything on the Internet.

Up until the 1990s, in pop music, we discussed so-called crossovers between two different genres such as heavy metal and hip-hop, or punk and reggae. Today, young bands from, say, Brooklyn, New York, happily tap into hundreds of sources, New Wave and cheesy middle-of-the-road pop and African beats and Brazilian bossa nova and English folk rock and what have you. In art, it’s similar. A few years ago, I wrote an article and made an exhibition on what I called “Romantic Conceptualism,” detecting a strand of conceptual art that had been present from its inception in the 1960s, but had only become fully apparent through the contemporary work made in its wake. In other words, artists had been looking at the monolithic-seeming last avant-gardes of Pop, Minimal, and Concept and had started to notice contradictions and seemingly peripheral figures, which they explored and put center stage. In the case of Romantic Conceptualism, the work of artists such as Bas Jan Ader seemed to call conceptual art’s apparent emphasis on cool rationalism into question. With regard to the 1990s and up until very recently, one can speak similarly of Psychedelic Minimalism, Libidinal Minimalism, Pop Abstraction. Not to forget the many re-evaluations of older avant-gardes: looking at constructivist or surrealist legacies with, for example, the new political landscape of Eastern Europe in mind, or re-evaluating gender and sexual orientation.

To some extent, I think that phase is over. Now these re-readings have basically been done. The upper echelons of the art business may have always preferred label clarity—an immediately recognizable visual style—and while this attitude may persist, it will be less than ever before where innovation actually occurs. Further mutations and atomizations will take place that not only question the distinctions and contradictions between genres and styles, but structurally evaporate the very notion of genre and style. This is actually less “new” than it may seem: since the 1960s, there have been artists such as Bruce Nauman or Mike Kelley or Rosemarie Trockel who absorbed an enormous variety of methodologies, ideas, and styles into their practice. Ai Weiwei is arguably another example. I would argue that this kind of approach, for the first time, will become fully hegemonic. Does that mean all will be ruled by indifference—anything goes, you can present any absurd, multiple combination of things as art? No; it just raises the bar. Amidst the sea of possibilities, in order not to drown, you have to make yourself a raft of whatever you find. It’s not the cleanest raft that counts, but the one that takes you the furthest. There are artists such as Ming Wong, a Berlin-based Singaporean artist making wildly eclectic but super-succinct “mutated” remakes of all sorts of scenes from film history; or Roee Rosen, an Israeli artist who—besides actually breaking taboos, in the guise of role-play and parody—leaves no stone unturned in mixing up genres and disciplines and political forms of expression and ways of embarrassing yourself, all to further the cause of art. When I see that kind of work, I think it proves that the perversely hybrid nature of today’s cultural and political landscape has had an effect on the tendency of art to settle into one aspect of the triad of production, distribution, and consumption I previously described—now, it seems all three are turned into a wildly whirling medley, and again it’s hard to resist the comparison to the Internet’s effect of equally blurring the lines between production, distribution, and consumption more radically and fundamentally than ever before.

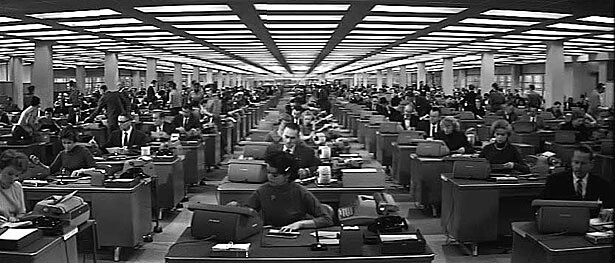

In an article I wrote a few years ago about Richard Artschwager—another predecessor of today’s freestyle mutationalism—I tried to explain his odd position at the edges of Pop, Minimal, and Concept with an allegory involving people in an office building.14 In 1981, Artschwager had realized an installation called Janus in the Hayden Gallery at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It made the viewers feel as if they were in a chrome-framed, oak Formica elevator. On pressing the buttons in a panel in the wall, small lights lit up one by one accompanied by the rushing sound of an elevator in motion till the desired floor had been reached. On the basis of this work, it was possible to liken Artschwager’s position in the context of Pop, Minimal, and Concept art to that of an elevator in a New York office building, the kind one sees in the opening scene of Billy Wilder’s comedy The Apartment. Pop artists hang around on the streets and in the lobby, some have their noses pressed against the show windows of boutiques, some are leafing through fashion journals at the newsstand or buying themselves a hot dog at the kiosk. The eyes of the minimalists sweep indifferently across the scene, then travel along the flat and monochromatic grid of the facade all the way to the opaque paneling of the executives’ upper floors. The conceptualists are already looking around in the accounts-and-planning department when Artschwager’s elevator, paneled with Formica and resonant with surreal Muzak, glides past all the floors—from the lobby past the accounts-and-planning department to the executive floor and down again. Where are the young contemporary artists in this scene? They are taking on all of the roles available, as if they were on loan from a temporary employment company. They are the plumbers and window cleaners, the visiting CEO landing on the roof in a helicopter, the bike courier, the tourists who go up to the top-floor panorama restaurant. Whether this is all a travesty, or actually leads to something, will hopefully be clearer in a few years’ time. In any case, the diagnosis of a “corruption” of art by its conditions in capitalist society is to be taken as a starting point, not as the reason to bewail a final stage.

According to Marx, the fetish commodity, as if by magic, renders the work that went into producing it invisible. In contrast, luxury products often highlight the specialized handicraft that went into producing them. Maybe one of art’s jobs is to continue finding ways to position itself like a stoppage in the gap between these two versions of the object, playing them off against each other, even by way of repudiating objecthood itself. This also means preventing consumption and production from being presented as a seamless continuum. Against this background, denouncing the “now” as mere novelty is fruitless: it erases the question of what is new, the undeniable existence of, for example, new ways of waging war or torturing, or, just as well, new cures and remedies against diseases. The fact we have to face is that art, probably, is torture and remedy in one.

See Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

See “lollipop,” Online Etymology Dictionary, →. Alternatively, it may be a word of Gypsy origin related to the Roma tradition of selling apples dipped in red candy and placed on a stick, the term for which is “loli phaba” (red apple).

See “The History of Lollipop Candy,” CandyFavorites.com, →.

Lawrence Alloway, “The Arts and the Mass Media,” Architectural Design 28 (February 1958): 34–35.

See Arthur C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981).

Richard Wollheim, “Minimal Art,” Arts Magazine (January 1965): 26–32.

Robert Morris: “[O]ne is more aware than before that he himself is establishing relationships as he apprehends the object from varying positions and under varying conditions.” Robert Morris, “Notes on Sculpture II,” Artforum 5, no. 2 (October 1966): 21.

See Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (London, New York: Continuum, 2006).

See →.

Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum 5, no. 10, (Summer 1967), 78–83.

Reproduced in Art in Theory 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul J. Wood (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 1992), 894.

Boris Groys, “On the New” in Art Power (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), 22–42.

Boris Groys, “Multiple Authorship” in Art Power (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), 92–100.

Jörg Heiser, “Elevator. Richard Artschwager in the Context of Minimal, Pop and Concept Art,” Richard Artschwager: The Hydraulic Doorcheck, ed. Peter Noever (Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Koenig and MAK Vienna, 2003), 49–60.