I once had a boyfriend with a very sensitive nose. It wasn’t that his sense of smell was particularly extraordinary; on the contrary, it was rather bad. It was that his nose could hardly be touched without him emitting a suffering ouch! and immediately protecting his organ from further violation. Needless to say, I often happened to be the involuntary cause of this pain, and of his exclamation “no, no, not my nose!”

I often remembered this ex-boyfriend’s nose when I started to have issues with my own nose in the summer of 2016, although my symptoms were different. I also thought often of Nikolai Gogol’s famous short story The Nose, as well as Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical conclusions about the naso-genital relationship, the fetishistic allure of the nose’s shine and phallic character. The latter was developed by Freud’s close friend Wilhelm Fliess who—unfortunately, and almost fatally—convinced Freud of its relevance. All if this came back to me last year, when I curated “Insurgency of Life,” a retrospective exhibition of Goldin+Senneby’s work.

1. My Fellow Traveler

As for my nose, it has demanded special attention since I was a child. Being prone to allergies, I blow my nose often, and use nose spray regularly. In 2016, the issues began in May with a simple cold caught on a trip to Singapore, which settled firmly in my snout. Week after week, this fairly prominent organ of mine was blocked, while at the same time continuously running, regardless of how much I cleared it. Now, you might find this too private—other people’s snot can be even more difficult to deal with than one’s own—but it is necessary to outline how relatively common symptoms turned into something quite unexpected.

There was no fever—the rest of my fifty-year-old body felt perfectly fine. There was just this blocked, and simultaneously running, nose of mine. After a month, I went to see a doctor in Stockholm who prescribed a course of antibiotics. But the snot kept running and the nose remained blocked. Two weeks later I went back to the clinic and, as it goes with the medical system in Sweden, I saw another doctor, only to be prescribed another course of the same antibiotics. It was high summer in Sweden and I began to feel out of place with my out-of-the-ordinary nose. I had to organize a special high-volume delivery of tissues to the island in the Stockholm archipelago where I spent vacation. Still no improvement. It was exhausting, and terribly annoying.

There was no other choice than to visit the doctor again. This third doctor determined that the problem was the kind of antibiotics I had been taking, and quickly prescribed another brand which would surely stave off the problem. This was at the end of July, the day before I would leave for South Korea to install and inaugurate the 11th Gwangju Biennale. Temperatures past 40 degrees Celsius and high humidity levels welcomed me there. All the while my nose was running, and still blocked. Then grinding headaches appeared with increasing intensity, which sometimes prevented me from speaking. Finally, my biennial colleagues convinced me to go to the emergency room at the local hospital, where I signed in at 5 p.m. on a Friday afternoon.

By 9 p.m. the same evening I was lying on a surgery table, surrounded by a swarm of people dressed in white. A scan had revealed that the entire sinus—from the hollow parts around the nose up to the forehead, and further still to the paranasal cavities in the cranial bones—was full. My brain and eyes were threatened. The sinus turned out to be completely stuffed with nasal secretion so thick that it could only be removed mechanically. I was put to sleep, and upon awakening, my nose was sore. Very sore. The anesthetics made me nauseous. Smiling, a friendly doctor reported that the surgery went well: my sinus had been successfully emptied. They had also identified the cause of my peculiar nasal adventure: a creature. To be precise, a fungus. This particular fungus is common in hot and humid areas across the planet, thriving inside human noses, where it is wonderfully warm, damp, and dark.

In other words, for almost three months I had lived with another living entity. But this fellow traveler was different from the kilograms of bacteria we carry around. This fungus had decided that my body, my sinus, was perfect for its development. Expressing my surprise to the doctor, he in turn shocked me when he confessed that while I was under anesthesia, he had taken the liberty of performing a nose job on me. Which he then followed by asking if I enjoyed downhill skiing in that faraway northern homeland of mine. Though downhill skiing always frightened me and I had gone to some lengths to avoid it at school, the news of the nose job frightened me even more. Considering how popular it is for women in South Korea to reshape their noses, which mostly means diminishing them, and not having looked at a mirror after the surgery, I feared the worst. In Korean terms my snout is big, and a nose job would have surely provided me with a smaller one. As I scrambled for my purse containing my pocket mirror, the doctor continued: we discovered that your right nostril was narrow and crooked, so we have widened it and straightened it out.

While this might have amused Freud, who also had issues with his nose, it would probably have been less entertaining to his close friend, the nose, ear, and throat doctor Wilhelm Fliess. Interested in the relationship between the nose and the genitals, Fliess introduced the concept of “nasality” instead of “anality.” According to Fliess, the nose is simply a sign of the penis, with the swelling of nasal mucosa leading to a “Fliess syndrome.” Freud’s nose problems were subsequently treated by Fliess, an otorhinolaryngologist who experimented with cocaine as an anesthetic. Freud fared better than another of Fliess’s patients, Emma Eckstein, who was treated by Freud for hysteria and became a psychoanalyst herself. Fliess almost killed her by forgetting gauze inside her nose while operating on it. This unfortunate event led to one of Freud’s most well-known dreams concerning Irma’s injection, which became key to The Interpretation of Dreams. The dream is said to deal with Freud’s anxiety around allowing Eckstein’s mistreatment, through the dream function of displacing the latent content—which is connected to wish fulfillment—with manifest content, i.e., the scenario of the dream. It is noteworthy that the nose has played such a seminal role in the development of the principle of displacement—a major trope for today’s contemporary art.

Whereas Freud’s and Eckstein’s noses were given medical treatment, in Nikolai Gogol’s satirical magical realist story in St. Petersburg, the nose disappears. One morning a barber finds a nose in his breakfast bread, while at the same time a civil servant looking for a pimple discovers that his entire olfactory organ has gone missing. Wild speculation about the disappearance and fate of the nose arise, until one day it comes parading down Nevsky Prospect wearing a full uniform and a plumed hat. The sword-carrying nose continues traveling around the city claiming to be a state councilor until the police return it to its rightful owner, who returns it to its rightful place. Expressing his befuddlement, Gogol’s civil servant exclaims that authors ought to write about such a strange thing happening.

2. Enemy Invaders

And here I am, attempting to put my own nasal adventure into words. It feels a bit odd as I am not used to writing about myself, and even less about my body. And yet, this adventure was a transformative experience: a close, even intimate, encounter with another creature, a new arrival reminding me of the relentless contingency of the life I live alongside so many others. In Donna Haraway’s terms, I ended up being-in-encounter with another “critter.” I had an inner sputnik, a traveling companion—a stowaway to be precise. For a moment, our shared material habitat made us companion species, where the one invisible to the naked eye almost knocked out the towering host. Not only did the experience lead to a very situated knowledge, it was indeed a multispecies encounter that surpassed sympoeisis to become making kin. I was forced to coexist with this other creature, and I had to deal with the situation and accept our shared condition. Eventually the kinship did not work out. I had the upper hand and forced the fungus out of my body, with the help of Western medicine practiced by a South Korean doctor.

Insisting on multi-relationality across conventional borders, Haraway’s writing, and especially her neologisms, practice the “worlding” that she describes. She hints at this implying the creation of something that goes beyond the status quo: internally and externally, this planet can no longer afford to remain the same. Like artists, she gives form to what is not yet there for us to grasp. She is trying to take response-ability for the condition we are in by using a new vocabulary to emphasize critical points. A new condition inevitably demands other ways of describing and dealing with it. Just as a young revolutionary society like the nascent Soviet state and its hitherto unheard of form of society needed a new human, it also needed new forms of relationships between people. In this way, Haraway’s “Terrapolis”—a speculative fabulation of a space for multispecies becoming-with—can be compared to the strongest contemporary art projects, or, in her words, “art science worldings as sympoietic practices for living on a damaged planet.”1

The allergic fungal sinusitis I was diagnosed with probably had to do with my allergic sensitivity to pollen and cats, as well as all fresh fruit and most vegetables. As a psychological and social tendency, oversensitivity is familiar in popular culture as well as in the fine arts. We know a lot about high-strung individuals and their inner life, whether male geniuses, hysterical women, or something in between. In comparison, physical oversensitivity is not very well understood in medicine, culture, or society. And yet I share the condition with many other people. The World Allergy Organization states that 10 to 40 percent of the world’s population suffers from allergies. They predict that by 2025, half of the population of Europe will suffer from one allergy or another.2

It is well-known that allergies are the immune system’s response to substances it cannot tolerate, treating otherwise harmless material in its environment as threats to be fought. The normal condition for the body should be peace—there is no reason per se to fight pollen, cats, fresh fruit, or even vegetables—yet this condition causes the body to forcefully defend itself, even declare war against enemy invaders. It is a kind of corporeal alarm giving way to a state of exception for the organism. This in turn can easily become a semi-permanent or even permanent state of exception, as with long-term states of emergency in countries like Syria, where it lasted for nearly fifty years (1963 to 2011), or for two years (2015 to 2017) more recently in France.

In reality, this immunological condition is a distant relative to autoimmune diseases such as AIDS and multiple sclerosis. These diseases are markers of our time; where the former carries the burden of a stigmatized new disease signifying an important moment of both solidarity and hostility in Western societies, the latter primarily afflicts the wealthy northern hemisphere. Furthermore, multiple sclerosis is three times more likely to be found in women than in men, which is fitting for a disease first described in 1884 by the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who famously researched female hysteria, and who also had considerable influence on Freud’s work.

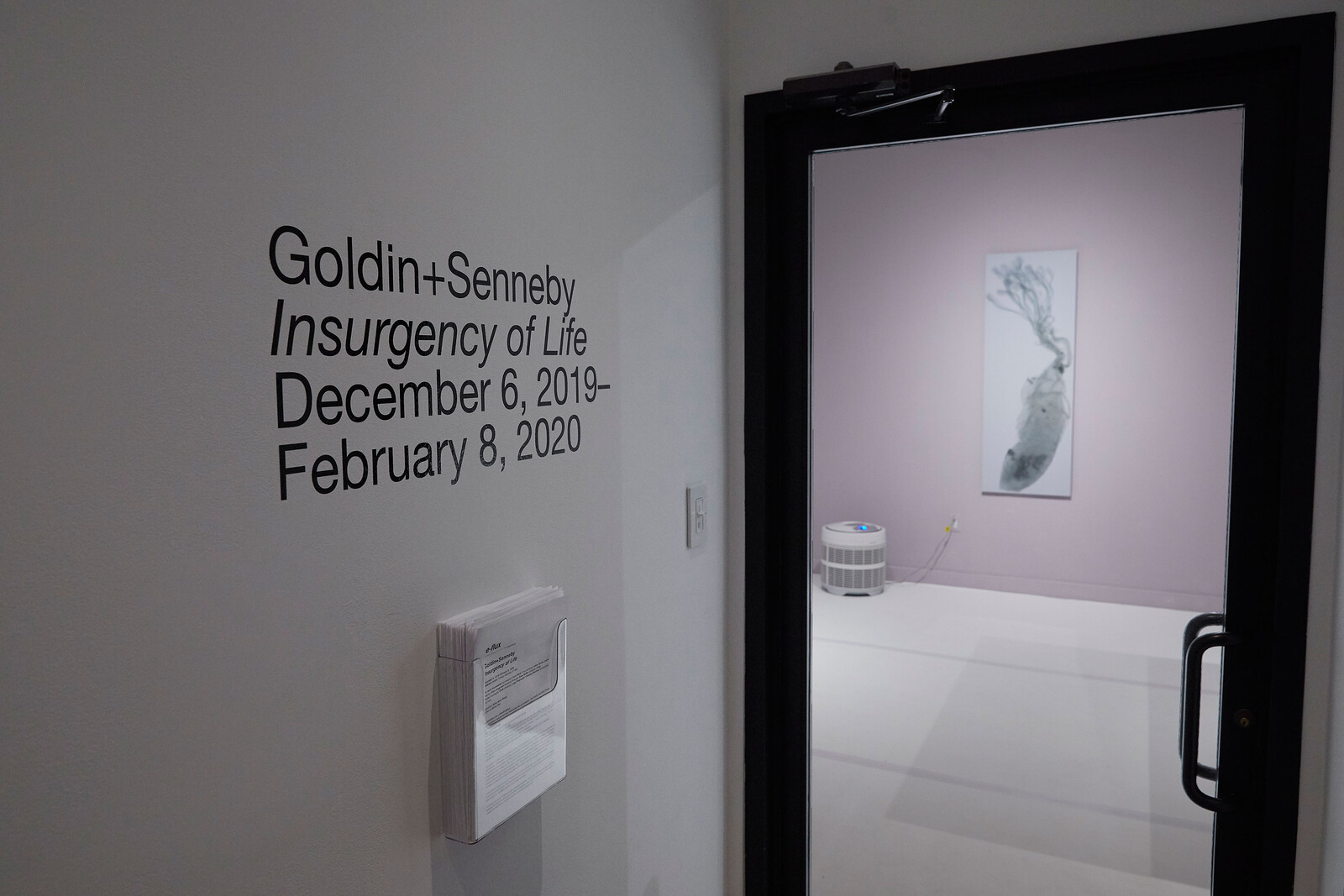

Goldin+Senneby, Insurgency of Life at e-flux, New York, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy: the artists. Photo: Gustavo Murillo Fernández-Valdés.

3. Insurgency of Life

Curating Goldin+Senneby’s exhibition “Insurgency of Life” at e-flux in New York last year brought me back to issues of autoimmunity. The exhibition centers on a fungus called Isaria sinclairii, and was introduced by the artists with the following passage:

You remember it as a stressful period.

You had started a new job and your relationship was out of balance. Your partner had left for France and communication was difficult. You travelled to Paris so you could talk.

Your left foot went stiff.

Part of your abdomen went stiff, just around the solar plexus.

Actually maybe more numb than stiff.

The kind of numb, tingling sensation that you can have when your arm falls asleep. The pins and needles sensation. For a moment you can’t locate your arm. You can’t move it.

Only this time the moment of numbness, of paresthesia, was extended. It went on too long. Your foot was numb. Your solar plexus was numb. And it wouldn’t go away.

You assumed it was psychological. Related to stress. The emotional stress of your crumbling relationship.

In an elongated clinical space with pale violet walls and bleachers at either end, the Isaria sinclairii fungus was cultivated with vast amounts of nutrient agar in a stainless-steel pool on legs. Contrary to that of my ex-boyfriend, when unblocked my nose is one of my most developed senses. Already before entering the exhibition during install I was worried about the potential smell of this impressive fungal pool, and the prospect of another habitat being made in my nose. As I entered, the smell was distinct but faint, vaguely similar to a forest. Used as a youth elixir in traditional Chinese medicine, this fungus is hyper-selective, or we might say oversensitive, in its choice of habitat. In the wild, it seeks out and exclusively grows on cicada nymphs when they are hatching below ground. After colonizing the cicada, the fungus eventually grows and sprouts from its head. This violent drama, whose visual appearance is not unlike images of the so-called mushroom clouds of atomic bombs, was captured by Goldin+Senneby on a large X-ray photograph hung on the wall facing every visitor entering the exhibition space. Again, I was reminded of “my” fungus, which similarly threatened my eyes and my brain.

The Isaria sinclairii fungus cultivated in the exhibition is used in a medication called Gilenya, which 50 percent of Goldin+Senneby, Jakob Senneby, used to take for multiple sclerosis. Diagnosed with the nervous system disease in 1999, Senneby participated in a clinical trial for this new medicine developed by the pharmaceutical multinational Novartis as the first ever pill-based MS treatment. As all treatments of autoimmune conditions suppress the immune system, the long-term consequences of such treatments are still largely unknown. In the US, the FDA recently warned that stopping Gilenya could cause severe flush-out effects that can worsen the condition severely and irreversibly. It is well-known that pharmaceutical companies, like insurance companies, are some of the most aggressive data harvesters of our time. Learning from patients posting tutorials on YouTube, the artists had ten Lego robots made, each carrying a smartphone rocking back and forth to making the pedometers tick. The rocking sound became a soundtrack that might have sounded like grown-up cicadas at dusk who, unlike their young counterparts, escaped the cruel fungus.

These DIY cheating machines are meant to trick the insurance companies who monitor physical activity to discount the cost of health care. Similar to the demand that Facebook should pay wages to those who indirectly work for them by providing content through our online activities, the Lego robots restore value to those who are deemed sick. Just as we might demand the restitution of ancient artworks and other objects, we might do the same with the most intimate of things: our body. As a way to reclaim the biological human body—and prevent the invasion of privacy—the Lego robots are a refusal to comply with a wholesale capitalization of very individual experiences, extracting ever more data, presumably indexical data, to most likely be used for marketing or research, the risks of which became apparent to Senneby in the Novartis trial.

As a focal point in the exhibition, the fungus-cultivating pool took as a reference Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting Fountain of Youth from 1546. Set in a forest with fantastical mountains in the background, the painting centers on a rectangular pool with steps on each side descending into the water. If the exhibition space at e-flux bore some resemblance to an anatomical theater, the painting offers the image of a stage for a drama of revitalization. Herodotus described how the fountain of youth’s magic water grants eternal life, and Cranach’s painting depicts old, crippled, and feeble women being taken to the pool in carriages and wheelbarrows to receive a rejuvenating bath, from which they emerge on the right side of the painting with smooth and erect bodies and long, wavy ginger hair. Awaiting them on this side are knights and other men with whom the rejuvenated maidens dine, dance, and probably engage in some amorous activities. In our own era, such erotics of longevity and immortality are expressed differently, from Silicon Valley executives receiving transfusions of teenage blood to more general longings for healing, convalescence, and recovery from any and all disease.

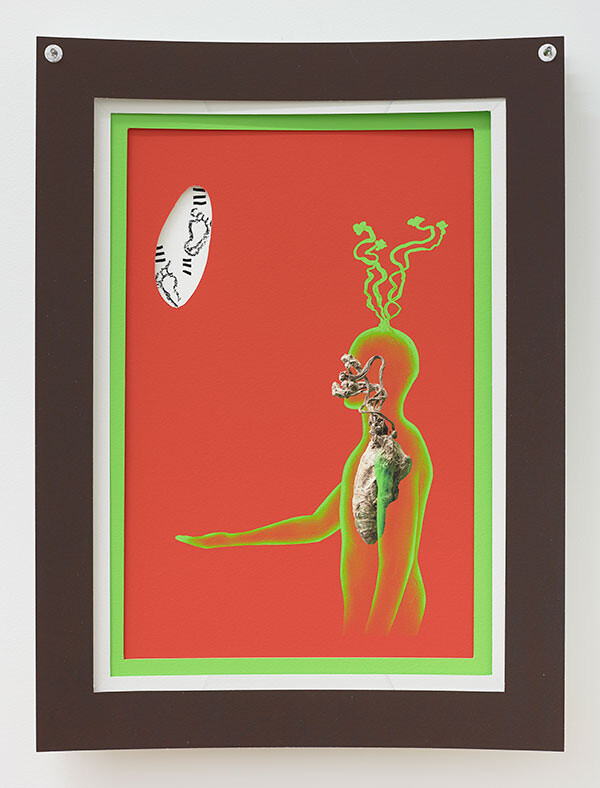

In a small room at the back of the exhibition space, a series of surrealistic drawings bore the iconography of the story of “Insurgency of Life.” Each drawing was made of ten layers stacked on top of each other, with cut-out holes in each layer, and were inspired by Tove Jansson’s acclaimed 1952 children’s book The Book About Moomin, Mymble, and Little My.3 As a story about a motley crew of critters imbued with a strong sense of both magic and realism, they could be a distant cousin of Gogol’s story, giving space to the fantastical while the relationships and feelings of the characters are plausible and realistic. A unique feature of Jansson’s book is that each spread has a hole allowing the reader to peek onto the following spread. In the story, Moomin—who, like all Moomin trolls, has an enormous round nose that would have intrigued both Freud and Fliess—is supposed to bring a bottle of milk to his mother. Carrying it through a forest and a rocky landscape, Moomin encounters a mix of scary and friendly creatures, all sharing the harsh weather conditions. When he finally reaches his mother’s sunny, blossoming garden, the milk is sour. But rather than the storyline, it is the form of the book that is of interest: the peek onto the next spread underscoring connections and relations, continuity and storytelling.

To work sequentially with a particular project over an extended period of time is characteristic of Goldin+Senneby’s work. Each component leads to the next, planting seeds for the sequels. Made up of multiple parts, this long-haul tactic requires a sort of persistence to be able to “stay with the trouble” (in Haraway’s words) and tell an incredibly complicated story emphasizing interconnectivity, causality, and a certain kind of feedback. Yet, despite the physical body of the artist being out of sight, it is at the very center of “Insurgency of Life.” It is the site. Like in Mary Kelly’s 1976 feminist classic Post-Partum Document—a six-year inquiry into childbirth and the development of the relationship between the mother and the infant—the body itself is nowhere to be seen. Such a displacement is followed by “real” indexical objects: for Kelly, diapers and parts of blankets, while for Goldin+Senneby the body is displaced by the body of the fungus. Avoiding anthropomorphism without abandoning the materiality of the body becomes a way to make something highly personal without being private. Simultaneously, and in contrast to their previous work, the artists are suddenly present in the flesh, doing a lecture performance at the opening.

Goldin+Senneby with Johan Hjerpe, Illustration in Seven Layers, 2019. Courtesy: the artists. Photo: Gustavo Murillo Fernández-Valdés.

4. Climate Change from Within

With “Insurgency of Life,” life itself has broken into the work of Goldin+Senneby, opening a view onto a situation that has accompanied the duo since they started working together fifteen years ago. However, this situation—and its stark medical reality—has not been detectable in their art until now. Between care and extraction, this version of the retrospective traced a physical condition, not a sequence of works. Forming the third and final part of a trilogy of retrospectives, the New York edition quite literally entered a different kind of biopolitics than both their previous work and their retrospectives in Stockholm and Brisbane.4 In New York, the duo relied again on a group of steady collaborators, outsourcing many parts of the work. Compared to their multi-year project Headless, “Insurgency of Life” is less concerned with neoliberal subterfuge. While they still outsource many tasks, with time, their service providers have become more like collaborators. In this way, they are foregrounding a network of dependencies more than one of anonymities. Accepting this kind of proximity and continuity does appear to become a process of immunization.

The exhibition was also the beginning of a new novel, written incrementally by the acclaimed author Katie Kitamura. As opposed to Headless, Goldin+Senneby’s experimental 2015 novel, this new novel has exited the world of offshore finance only to enter the field of gene manipulation and bio-capitalism. During the course of the exhibition, a performance entitled Crying Pine Tree took place at Triple Canopy, where Kitamura read from her first chapter of the new novel. Here, the main character, a gene-manipulated and autoimmune pine tree, encounters an investor and a geneticist who accelerate and exaggerate the immune system of the conifer in order to make it produce more sap. As a source for clean energy, the sap might prove in the long run to be a kind of liquid gold, in addition to being a natural disinfectant used since antiquity to treat wounds. Hovering between science, art, and fiction, the narrative of the novel displaces the immunological concerns of MS onto the flora. For years to come, the writer and the artists will feed each other’s creative process by allowing each step to infuse the next one.

But what is the body at stake here? It is an artistic double-body—individual and singular, yet at the same time collective—which already complicates the tradition of retrospective exhibitions. Compared to a lot of performance and body art of earlier decades, the relation of this double-body to the self is already intensely, and differently, politicized. Whereas before, it elaborated the elusive anonymity of offshore finance in Goldin+Senneby’s Headless, today it opens onto the absolute situatedness of disease. Now it is springtime again, and as I am blowing my nose in self-imposed quarantine due to Covid-19, I have begun to suspect those of us affected by immune-related conditions to be an involuntary avant-garde. Placed at the forefront of how illnesses develop today, our bodies become the site for a parallel climate change from within. In order to begin to grasp this, we need, among other things, a sequel to Michel Foucault’s 1961 Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. Perhaps it should be called something like Oversensitivity and the Planet: A History of Immunity in the Age of Profit.

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016), 67.

“This 150 million figure is predicted to increase exponentially and it is estimated that by 2025 more than 50% of all Europeans will suffer from at least one type of allergy, with no age, social or geographical distinction” →.

The direct translation of the original Swedish title is “What Happened Next?”

Such a long-haul trajectory is echoed in their series of retrospectives that have been going on for four years. Since the birth of retrospective exhibitions in the early nineteenth century, a retrospective typically entails temporarily assembling as many works as possible by one single artist under one roof during a few months—the purpose being to make artistic developments manifest, and offer the chance to compare them to other artists’ developments. As is obvious, Goldin+Senneby have chosen other routes. The first retrospective in their trilogy, “Standard Length of a Miracle,” encompassed a set of existing works displayed in five different locations across Stockholm, most of them non-art related. At the same time, a handful of brand new works were presented at Tensta Konsthall and Cirkus Cirkör, all feeding on a “protocol,” a short story commissioned for the occasion from the author Jonas Hassen Khemiri. At the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane, the second retrospective consisted of bootleg copies of old works.