Just half a year after Australia elected yet another climate-sceptic government, the country was set ablaze by tornadoes of fire. In November 2019, a few hours after the Council of Venice rejected a climate crisis plan, its parliament literally flooded.1

If any illusions remain that only humans have world-making agency in our ecosystem, the consequences of the racial Capitalocene are forcing these to an end.2 The Capitalocene’s trajectory was to establish “capitalism as world-ecology,” but the truth is that the brutal realities of its extractivist industries have enabled various parts of our violated ecologies to strike back: by hurricane and earthquake, by plastic flood and toxic fire.3 And now, the coronavirus pandemic predictably makes visible how structural inequalities are accelerated through what is still a relatively containable crisis, and this tells us much about what to expect from the current world order when faced with vastly more aggressive climate catastrophe–fueled pandemics, failed harvests, and millions of climate refugees.

The Capitalocene’s burning of fossil fuels has accelerated our becoming fossils-in-the-making.4 Thus, human propagandas—narratives, imaginaries, and even infrastructures—can no longer claim to solely author the world, as if that world was a mere passive resource waiting to be extracted from and molded in our interests.5 Now other actors and agents in that same world—such as extreme weather—extract from and author us just the same. Even our choreographies are beginning to turn Pyrocenic, relating to fire and lack of oxygen, as was demonstrated at the visionary 2019 The CyberCunt Mini Ball by Father Chraja Kareola, where one performance category was based on the structural absence of oxygen and performers were equipped with breathing masks in order to inhale air necessary to enact their next move.6 Quoting from the program, led by the House of Kareola: “Oxygen has come to be a luxury only for the rich few. Tell us your own suffocatingly musical story, wearing an oxygen mask in order to be able to survive.”7

Nonetheless, our propagandas will still substantially define whether humans will have a place in the future worldings of this world and whether meaningful survival within it remains an actual possibility. Considering the present pandemic, what are the current climate propagandas that compete over the possibility of human existence in our new ecosystem of floods and toxins?

Digital rendering of floating island by The Seasteading Institute and Kostack Studio, 2017. Originally to be trialed in French Polynesia, the government revoked its deal with the institute in 2018.

1. Ecocidal Markets, the Flat Earth Anti-globe, and the Specters of Eco-fascism

While neoliberals, libertarians, right-wing conservatives, conspiracy theorists, and the alt-right might at large deny the reality of climate catastrophe or severely downplay its impact, ecocide nonetheless serves as the raw material for these political ideologies to spin climate propaganda of various kinds. Think of what T. J. Demos describes as the “neoliberalization of the Anthropocene,” in which the collapse of ecosystems is primarily perceived as a resource for new geo-engineering industries.8 In this propaganda narrative, a market structured on the resource of our impending extinction is the only way to overcome that very extinction and brand a future for us in the process: whether it is through Peter Thiel’s libertarian Seasteading Institute that aims to produce floating stateless islands where Ayn Rand–style objectivism rules, or through Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which aims to terraform Mars for the sake of the survival of the earth’s one percent.9 The futurological appeal of Thiel and Musk’s biosphere architectures—situated in a flooded world or terraformed planet—results from a public-relations approach that markets ecocide as an investment opportunity. Furthermore, the new infrastructures of this flooded world are already manifesting in real time: in the form of giant dams to enclose the North Sea, or the use of “sea barriers” to block (climate) refugees from navigating the Great Drowning, to give just two examples.10

For the more traditional brand of neocons on the other hand, climate catastrophe has been a vivid reminder of the need to reestablish US empire in the context of the ongoing War on Terror. Joseph Masco reminds us of the conservative reporting on Hurricane Katrina, which did not address the causes for this unnatural disaster and its racialized origins and impact, but instead framed it as an anti-terrorism exercise and call for further militarization: if this would have been a terrorist attack, does it not prove how badly prepared the United States would be to face the next Axis of Evil?11 Neoconservative climate propaganda refuses to acknowledge either the material reality of neocolonial extraction as a material cause of climate catastrophe, or the fact that the Capitalocene has equipped parts of our ecosystem with additional worlding agencies. Instead, the agencies unleashed through the climate catastrophe are turned into a political metaphor: nature acts as an allegory for the true danger, which is the human nature of the terrorist.

For the thousands of conspiracists who have joined various competing “flat earth societies”—some of which have developed theoretical frameworks and scientific experiments to prove that the earth is, in reality, flat—climate catastrophe is nothing more than a plot by NASA and its globalists compatriots, who have engineered the majoritarian conception that the earth is round. Their propaganda takes sculptural form in their production of flat-earth spatial models that aim to prove, among other things, that day and night are mechanically engineered in a Truman Show–style hoax—an obscure doubling from globe to anti-globe that has manifested in a similar way in the propaganda of Naomi Seibt, the climate-change-denying “Anti-Greta.”12 According to flat-earthers, it is not just climate catastrophe but our whole ecosystem that serves as a stand-in for the curtain behind which a secret, global, elite governing body engineers our fate.13

While these various propaganda narratives have enabled the increasingly uninhabitable earth that we are confronting at present, they have not yet reached their most dangerous phase. As Naomi Klein points out, a right-wing narrative that actually recognized the climate catastrophe as real would enable an even more violent specter of eco-fascism.14 Such a specter manifests in Elvia Wilk’s novel Oval (2019), where we are introduced to an eerie near-future Berlin haunted by unpredictable weather, where most residents seem to be flex-based consultants, some of which struggle for survival in geo-engineered environments such as the “Berg,” a fake mountain covered with malfunctioning eco-huts. This synthesis between brutal neoliberal precarization and doctrines of enforced, commodified sustainability shows the materialization of eco-fascism against the background of Berlin’s club aesthetics and synthetic drugs such as the Oval pill, which gives the book its title.15

An even darker take on the eco-fascist specter is seen in the popularity of the hashtag #ThanosDidNothingWrong, popularized on Reddit and other platforms, which references the cosmic opponent Thanos from the Avengers superhero franchise. In the two-part finale to the franchise, Thanos “solves” what he considers multi-galaxy climate crisis and overpopulation by annihilating half of the living beings in the universe—akin to the type of genocidal engineering that eco-fascism aims to bring about.16 Right-wingers who realize that ecocide is real will not respond by redistributing means for common survival, but by doubling down on the question of who has the superior racial right to survive and who does not—which, as Sherronda J. Brown argues, is one more reason to refrain from declaring humans the “virus” in the current coronavirus pandemic.17 That an official Trump War Room 2019 reelection video shows the president as Thanos, adopting the character’s words “I’m inevitable,” can be considered an early start to eco-fascist propaganda campaigns to come.18

Still from the “I’m Inevitable” Trump War Room campaign video, depicting Trump as The Avengers character Thanos, 2019.

The terrifying intersection of these climate propagandas—neoliberal, libertarian, neocon, conspiracist, and alt-right—culminate in the world aptly described by Octavia Butler in her novel Parable of the Talents (1998). Here we witness the rise of Texas senator Andrew Steele Jarret, who becomes the presidential candidate of the Christian America Movement, campaigning with the slogan “Make America Great Again,” in a world torn apart by extreme weather. In this deeply polluted and unstable landscape shaped by warring gated communities, where Thiel-style tech-corporations engineer contracts for lifelong serfdom, Jarret’s ultranationalist evangelicalism provides a sense of both moral superiority and a nostalgic return to an imagined past, as a substitute for real change. As protagonist Lauren Olamina observes: “Jarret insists on being a throwback to some earlier, ‘simpler’ time. Now does not suit him … There was never such a time in this country. But these days when more than half the people in the country can’t read at all, history is just one more vast unknown to them.”19

None of the examples of right-wing propaganda I have discussed so far attributes any efficacy to the various other-than-human agencies—from fire to flood, toxin to plastic typhoon—that now constitute our increasingly violent ecosystem. For neoliberals and libertarians, climate catastrophe is simply another market resource. For neocons, unnatural disaster is merely a metaphor for the real threat of terrorism. The conspiracists consider fires and storms nothing other than an attempt to distract us from globalist dominion. And the eco-fascists, once they do acknowledge the life-threatening changes in our ecosystems, consider it their closing argument for the rationale of (inter)planetary genocide. And all of this propaganda culminates in the uninhabitable world so aptly described in Butler’s futurological study—a future that, in far too many ways, has already become the present.

2. Liberal Climate Metaphors, Attenborough’s Empire, and a Novelization of the Green New Deal

While the liberal-democratic spectrum embraces climate science as proof of its superiority over what Hillary Clinton termed the “basket of deplorables,” it nonetheless propagates its own form of climate denial. We should not forget that the Andrew Steele Jarrets of this world—from Trump to Bolsonaro—are not the cause of climate catastrophe. Supposed common-sense liberals and greenwashing CEOs were aware of the ecocide to come for decades. The Biden-esque call to return to the status quo preceding the post-truth era amounts to a call for continuing the mass murder of terrestrial life, just with added presidential decorum.

In popular culture, this propaganda leads to a paradoxical recognition without recognition of the reality of climate catastrophe. For example, such (non)recognition pervades the recent third season of The Good Fight (2017–present), the “woke” sequel to the ultra-white The Good Wife, set in a majority-black Chicago law firm built by a veteran of the civil rights movement. Throughout the season, lawyers from the firm take on judges and alt-right agitators connected to the Trump regime, while trying to maintain a steady cash flow from their high-net-worth clientele. Extreme weather features in several episodes, culminating in a final episode where a “lightning ball” threatens the city. Nonetheless, not a single lawsuit brought by the firm addresses the need to reconceptualize rights beyond the human, as proposed by Radha D’Souza, who argues for a rejection of the liberal construct of “human” rights altogether.20 Instead, extreme weather does not lead to an acknowledgment of redistributed forms of agency in our ecosystem, but is simply reduced to a metaphor for the extremity of the Trump regime.

Even when it comes to liberal climate propaganda, as seen in the David Attenborough–narrated documentary Our Planet (2019), we have to be alert to the underlying ideological machinations. Attenborough’s benevolent voice of reason—also featured in recent high-budget and highly popular documentaries like Planet Earth, Frozen Planet, and The Blue Planet—is supposed to teach us both the beauty of nature and the threats “we” pose to it. He narrates footage taken by high-res cameras that penetrate ever deeper into remote forests and seas, extracting images of highly endangered species. The territorial British Empire might have crumbled, but its gaze, now directed through an army of cameras, still reaches into the far corners of our planet, always accompanied by that authoritative British voice that tells us how history began, how it will end, and how it can be saved. Is it not this obsessive gaze, this violent extractive gaze, that sealed the fate of the drowning polar bear featured in the series?

Attenborough is certainly not the main enemy here, but it is wildly inaccurate to suggest that a generic “we”—rather than fossil fuel CEOs and other climate criminals—bears responsibility for climate catastrophe, and the notion that human benevolence and individual choice is what is needed to “save” the planet seems closer to the problem than to a solution. We must instead acknowledge that our ecosystem is changing. It no longer consists merely of forests and icebergs, but also of toxic flooding and geographies of plastic. These new forms of agency must be the start of a broader political, economic, and social change. More than preservation, we need transformation.

A propaganda that does acknowledge the transformative agencies unleashed by climate catastrophe can be found in the Green New Deal, as formulated by figures like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Yanis Varoufakis.21 However problematic the conception of a “green industrial revolution” might be, with its embrace of the modernist category of “progress,” this project stands out by fully recognizing the transformations taking place in our ecosystem. Instead of denying their agency, it embraces them as a chance to massively invest in sustainable infrastructure, planet-wide wealth redistribution, colonial reparations, and a recognition of the frontline leadership of indigenous communities and people of color, who are disproportionately impacted by the climate crisis. In the Green New Deal, we change with—as part of—the climate.22 This opens up a pathway that is fundamentally different from what is referred to as “deep adaptation,” moving towards deep transformation instead.23

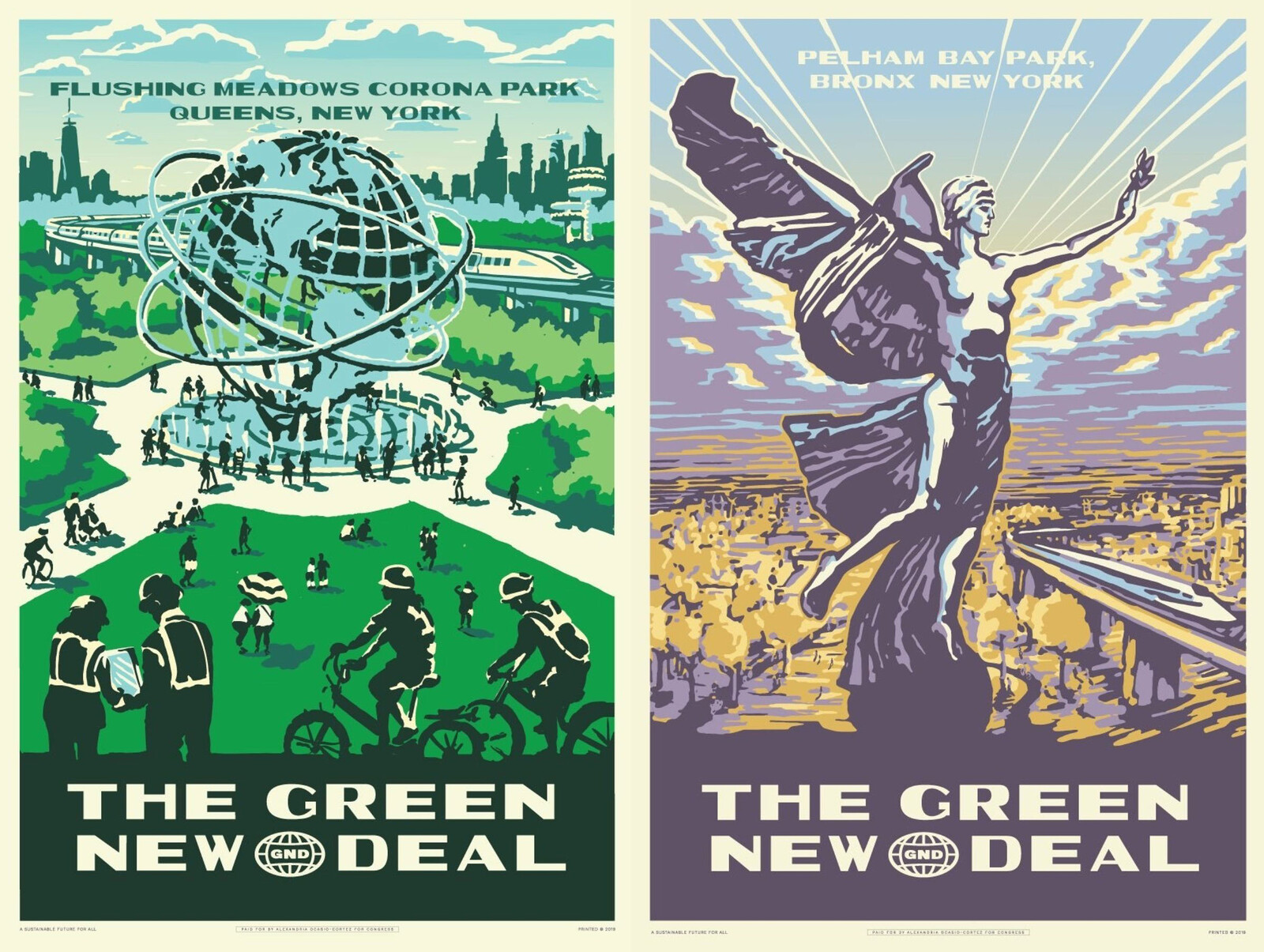

This egalitarian climate propaganda has also been translated into new forms of cultural production. One example is the Green New Deal poster series created collaboratively by Ocasio-Cortez, the artist Gavin Snider, and the design firm Tandem. Its retro-imagery depicts monumental landmarks in green public spaces crisscrossed by high-speed electric trains, the font and print style evoking the aesthetics of the Federal Art Project, a program of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s original New Deal. Playing out imagined pasts and futures, the poster series reads as climate fiction with a vintage filter. A less nostalgic take on the imaginary of the Green New Deal is the video “A Message from the Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez” (2019), developed by artist Molly Crabapple in collaboration with Naomi Klein and Ocasio-Cortez, which moves from cli-fi to climate realism. Speaking from a future where the Green New Deal has already been implemented, we hear Ocasio-Cortez narrate how impossible this political and economic transformation seemed in our present present, compared to how its principles—from sustainable infrastructure to universal healthcare and publicly funded elections—are the new normal in her future present. The closing statement of the film—“We can be whatever we have the courage to see”—emphasizes the role of the artistic imaginary in a climate propaganda that constructs a new reality—a new realism—in which we do not merely survive, but transform.24

Another aspect of the Green New Deal’s climate realism, which has been around as a conceptual platform since the early 2000s, is reflected in Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel 2140 (2017). Robinson’s narrative is situated in New York a century from now. The city is underwater after two massive planetary floods (the First and Second Pulse) that caused the seas to rise fifteen meters (fifty feet). Billions perished. While awaiting more extreme weather to come, cooperatives in the city’s so-called “intertidal zone” conspire to avoid yet another wave of gentrification, as speculators run wild in what they consider the “SuperVenice” of New York. For them, the rising water is nothing but a new market opportunity to buy up and resell high-rise apartments with seaside views, all part of the new century’s “high-frequency geo-finance.”25 But a new unexpected mega-storm lays waste to the coasts and pits the two forces—cooperative socialism and disaster capitalism—against one another. Banks demand that the government save them, whereas the cooperatives demand that the government nationalize the banks to fund a planetary Green New Deal and a new infrastructure for twenty-second century democratic socialism. In the wake of the First and Second Pulse, a new culture of resistance has emerged in a drowned New York, now capable of turning the shock doctrine against itself. As a citizen in the novel recounts:

Hegemony had drowned, so in the years after the flooding there was a proliferation of cooperatives, neighborhood associations, communes, squats, barter, alternative currencies, gift economies, solar usufruct, fishing village cultures, mondragons, union’s Davy’s Locker freemasonries, anarchist blather, and submarine technoculture, including aeriation and aquafarming. Also sky living in skyvillages that used the drowned cities as mooring towers and festival exchange points; container-clippers and townships as floating islands; art-not-work, the city regarded as a giant collaborative artwork; blue greens, amphibiguity, heterogeneticity, horizontalization, deoligarchification; also free open universities, free trade schools, and free art schools.26

In Stanley Robinson’s futurological study, climate catastrophe is not turned into a metaphor, but acknowledged as a deep and real transformative force that opens a pathway towards comradely coexistence and sympoeitic collaboration between the various agents—human, nonhuman and other-than-human—that make up this new ecosystem. But there is a problem with his basic premise, in which it takes a monumental planetary crisis a century from now to create the conditions for realizing the modest demands of the Green New Deal. This part of Robinson’s “realism” comes dangerously close to political nihilism. There have been too many sacrifices already, but in Robinson’s narrative the death of billions is needed to successfully implement a Bernie Sanders–type platform. Considering that the Green New Deal is already the absolute minimum we should demand for our present, this is ultimately unacceptable as a demand for the future.

Masked Halla takes down a drone by bow and arrow in the movie directed by Benedikt Erlingsson, Woman at War (2018).

Parallel to the Green New Deal—but critical of its progress-driven narrative—has been the emergence of Extinction Rebellion, which relies on civil disobedience, especially swarm tactics: interventionist blockades and “die-ins” that temporarily sabotage the consumer-driven and fossil fuel–reliant dynamics of urban environments. The cinematic equivalent of this civil disobedience can be found in Benedikt Erlingsson’s Woman at War (2018), in which the protagonist Halla employs contemporary guerrilla tactics to sabotage extractivist energy industries in Iceland and keep the government from signing a deal with China to open a new aluminum smelter. She writes in her anonymous manifesto: “I urge everyone to rise up and use their ingenuity to cause damage to these enterprises. That’s the only thing those psychopaths, those global multinationals, can understand.”27 Halla’s actions focus on sabotaging energy supplies and include blowing up electricity transmission towers, but like Extinction Rebellion, she makes sure to cause no harm to humans. Nonetheless, the corporate media portray her actions as leading inevitably to physical violence—showing that in the era of the Capitalocene, disrupting industry is treated as equivalent to taking human lives. However, Halla remains troublingly blinded by her whiteness (not unlike aspects of Extinction Rebellion).28 A South American backpacker suspected of committing Halla’s acts of sabotage is arrested multiple times, while Halla herself, as a white native Icelander, easily passes through checkpoints with winks and smiles. The film seems to make light of this embodied privilege when Halla wears a Nelson Mandela mask to avoid facial recognition by a police drone, perversely inverting the title of Frantz Fanon’s famous book: instead of Black Skin, White Masks, we see White Skin, Black Masks.

In contrast to liberal climate propaganda, which turns climate catastrophe into a metaphor and implies that mere human benevolence can “save nature,” democratic-socialist climate propaganda, embodied by the Green New Deal, highlights the transformative capacity of the crisis. In the case of Extinction Rebellion, we see a similar acknowledgment of the material reality of a changing climate and the need to restructure our society accordingly—although with severe racial blind spots when it comes to who has been the most impacted by climate collapse, and who has been on the front line in the battle against it. Nonetheless, these propagandas envision the possibility of a changed but potentially inhabitable earth. Or one where, at the very least, we can begin to redistribute extinction equally.

3. A Cosmopolitical, Terrestrial, and Primitive Communist Climate Propaganda of the Toxic Commons

What other climate propagandas aim to establish new comradely ecosystems between humans, nonhumans, and other-than-human actors, grounded in a fundamental historical awareness of the unequal distribution of extinction? Shela Sheikh builds on the work of Isabelle Stengers to propose a “more-than-human cosmopolitics,” in which “nature is imagined not only as a rights-bearing subject, but also a potential political subject—as a ‘citizen’ of a ‘cosmopoliteia.’”29 Sven Lütticken argues along similar lines that such a cosmopoliteia could take the form of a twenty-first-century “Terrestrial,” an organization modeled after the twentieth-century communist International, but now as an “organizational form for Terrans” that aims to deepen the fundamental opposition “between the Terrans and their Human enemies in (trans)national guises.”30 For the research group Toxic Commons, it is crucial to recognize the agency of toxins in the raging ecologies of the climate catastrophe.31 While mapping the neocolonial dynamics of the global toxic waste trade, Toxic Commons also calls for coexisting with our own toxicity: in-sourcing rather than outsourcing the agencies unleashed through extractivist industries.

Such endeavors to imagine more-than-human ecologies of comradeship are part of what the collective of artists, academics, and indigenous activists Not An Alternative refer to as the specter of “primitive communism.” The collective writes that primitive communism names a “collective mode of life that neither capitalism nor settler colonialism could fully manage, contain, or eradicate.”32 This specter could not be more fundamentally opposed to the specter of eco-fascism I started with. Not An Alternative’s battleground is the natural history museum, which has historically perpetuated the idea of a passive nature external to humans, which is simultaneously contemplated upon and extracted from. In radical contrast to this is the indigenous idea of the natural world as articulated by Not An Alternative, building on the work of indigenous academic Nick Estes, who is a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe: here nature is “inalienable,” and rivers and forests are “nonhuman relatives” that cannot be commodified. They continue: “The specter, as an absence that insists from within the capitalist world, connects living communists to their ancestors—the primitive communists of pre-capitalist times—and their descendants, those who have yet to take up the cause.”33

Not An Alternative’s climate propaganda manifests in their ongoing organizational artwork of institutional liberation titled The Natural History Museum (2014–ongoing). As part of this project, in 2015 they displayed a series of dioramas at the annual convention of the American Alliance of Museums—an organization of which they managed to strategically become a member. These dioramas illustrated what they called our “fossil fuel ecosystem,” highlighting in particular the impact of corporations owned by David H. Koch, the sponsor of the exhibition.34 Behind glass, a stuffed polar bear was surrounded by broken TV sets and car tires. This is nature in the racial Capitalocene: a combination of wretched earth, toxins, and nonhuman comrades struggling for survival in an altered ecosystem.35 But the work of the collective does not limit itself to these necessary forms of institutional critique. Their project Whale People: Protectors of the Sea (2018) concerned the endangered orca, known in the language of the indigenous Lummi Nation as “Qw’e lh’ol mechen” (our people that live under the sea). This project involved bringing a whale totem, created by Lummi Nation carvers Jewell James and the House of Tears Carvers, into the Florida Museum of Natural History. The totem had already traveled to various sites of environmental struggle across the country. Turning the exhibition space into a site of collective ritual, elders of the Lummi nation guided visitors in laying hands on the totem, collectively evoking the specter of a radically different natural history. This specter makes visible an opening (which Not An Alternative refers to as “the gap”) that has not been foreclosed by the racial Capitalocene, one that leads towards the possibility of a “dialectical struggle between extinction and resurrection.”36

From a more-than-human cosmopolitics to the Terrestrial, from our toxic commons to the specter of primitive communism—these forms of climate propaganda envision a radically different ecology where human, nonhuman, and other-than-human comradeship enables not merely survival, but transformation.

Angela Giuffrida, “Venice Council Flooded Moments after Rejecting Climate Plan,” The Guardian, November 15, 2019 →.

Jason W. Moore, “The Rise of Cheap Nature,” in Anthropocene or Capitalocene: Nature, History and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. Moore (PM Press, 2016), 85.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2011), 69.

I discuss at greater length the relation between narrative, imagination, and infrastructure in the context of propaganda in Jonas Staal, “Propaganda (Art) Struggle,” e-flux journal no. 94 (October 2018) →.

The Pyrocene, as proposed by T. J. Demos, is “the geological age of fire.” See Demos, “The Agency of Fire: Burning Aesthetics,” e-flux journal no. 98 (February 2019) →.

Quoted from the Facebook announcement for “The CyberCunt Mini Ball by Father Chraja Kareola.”

T. J. Demos, “To Save a World: Geoengineering, Conflictual Futurisms, and the Unthinkable,” e-flux journal no. 94 (October 2018) →.

Thiel’s supposed libertarianism is deeply contradictory, as Sven Lütticken observes: “That Thiel is obsessed with attaining sovereignty vis-à-vis the nation-state, for instance via ‘seasteading,’ did not, of course, prevent him from supporting Trump, who promises to restore national sovereignty and ‘make America great again’ … This is the double promise of sovereignty: the one per cent get one kind, the rest get national sovereignty.” Sven Lütticken, “Abdicating Sovereignty,” in Propositions for Non-Fascist Living: Tentative and Urgent, eds. Maria Hlavajova and Wietske Maas (MIT Press and BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, 2019), 81–95, 87.

Joseph Masco, The Theater of Operations (Duke University Press, 2014), 108.

David Smith, “‘Anti-Greta’ Teen Activist to Speak at Biggest US Conservatives Conference,” The Guardian, February 25, 2020 →.

See also the documentary film Behind the Curve, dir. Daniel J. Clark (Delta-v Productions, 2018).

Naomi Klein, On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal (Penguin Random House UK, 2019), 40–49.

In the novel, a pill called Oval provokes generosity in a scarcity-structured world. See Elvia Wilk, Oval (Soft Skull, 2019).

The subreddit r/ThanosDidNothingWrong even re-enacted Thanos’s galactic genocide in July 2018 by randomly removing 350,000 of its users—half of its membership. See Aja Romano, “Redditors Love Infinity War’s Thanos So Much, 300,000 of Them Just Faked Their Own Internet Deaths,” Vox, July 10, 2018 →.

Sherronda J. Brown, “Humans Are Not the Virus: Don’t Be an Eco-fascist,” Wear Your Voice, March 27, 2020 →.

Luke O’Neill, “‘I’m Inevitable’: Trump Campaign Ad Shows President as Avengers Villain Thanos,” The Guardian, December 11, 2019 →.

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Talents (Grand Central Publishing, 2007), 19.

Radha D’Souza, What’s Wrong with Rights: Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations (Pluto Press, 2018).

See the US Congressional resolution developed by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Edward J. Markey, proposed in both the Senate and House of Representatives on February 7, 2019 →. Varoufakis cofounded the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25), and a “European New Deal” is an integral part of the its platform →.

On the struggles over the Green New Deal, see Nicholas Beuret, “A Green New Deal Between Whom and For What?,” Viewpoint Magazine, October 24, 2019 →.

Jem Bendell, “Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy,” Institute of Leadership and Sustainability (IFLAS), University of Cumbria, July 27, 2018 →.

Transcript from Molly Crabapple and Naomi Klein, “A Message from the Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,” The Intercept, 2019 →.

Kim Stanley Robinson, 2140 (Orbit, 2018), 19.

Robinson, 2140, 209.

Transcribed from Woman at War, dir. Benedikt Erlingsson, (Slot Machine and Gulldrengurinn, 2018).

See Athian Akec, “When I Look at Extinction Rebellion, All I See Is White Faces. That Has to Change,” The Guardian, October 19, 2019 →.

Shela Sheikh, “More-than-Human Cosmopolitics,” in Propositions for Non-Fascist Living, 130.

Sven Lütticken, “Toward a Terrestrial,” e-flux journal no. 103 (October 2019) →.

Consisting of researchers, artists, and other cultural workers, Toxic Commons was founded by Caroline Ektander, Antonia Alampi, and the Hazardous Travels research group. It organizes conferences and research exhibitions that explore the notion of toxic agencies. See in particular “The Long Term You Cannot Afford,” October 26–December 8, Savvy Contemporary, Berlin.

Not An Alternative, “Beneath the Museum, the Spectre,” in The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change, eds. T. J. Demos, Emily Eliza Scott, and Subhankar Banerjee (Routledge, forthcoming).

Not An Alternative, “Beneath the Museum, the Spectre.”

See the website of the Natural History Museum →.

“The Wretched Earth” is the title of a special double issue of Third Text (vol. 32, no. 2–3, 2018).

Not An Alternative, “Beneath the Museum, the Spectre.”

Category

Subject

I want to thank iLiana Fokianaki and Andreas Petrossiants for their editorial support in writing this essay, as well as Not An Alternative, Radha D’Souza, Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei, James Bridle, Gene Ray, Chrysos (Chraja) Synodinos—Father of the House of Kareola—and Theo Prodromidis, for the generous conversations and exchanges underlying this text.