Continued from “Narcissistic Authoritarian Statism, Part 1: The Eso and Exo Axis of Contemporary Forms of Power”

In part one of this essay, I tried to offer a reading of new power formations by rethinking the current pattern of democratically elected authoritarian figures—brought to power with the help of multinationals vis-à-vis the globalized, neoliberal versions of the “state” and “state power.” By examining their structures and behaviors, I tried to situate, understand, and describe counter-hegemonic cultural practices that position themselves against the state. In part one, I also named today’s configuration of power “narcissistic authoritarian statism,” defining it as a neoliberal structure of power that merges old components of the nation-state with contemporary forms of corporate transnationalism defined by narcissism. I examined this corporate-state model of narcissistic authoritarian statism through what I called the “exo/eso axis,” in order to visually understand how two of its basic components—territory and legitimacy—are expressed within and without its literal and metaphorical borders. Using territoriality, I looked into different artistic practices that propose collective action and organization as a counter-hegemony to this corporate-state model.

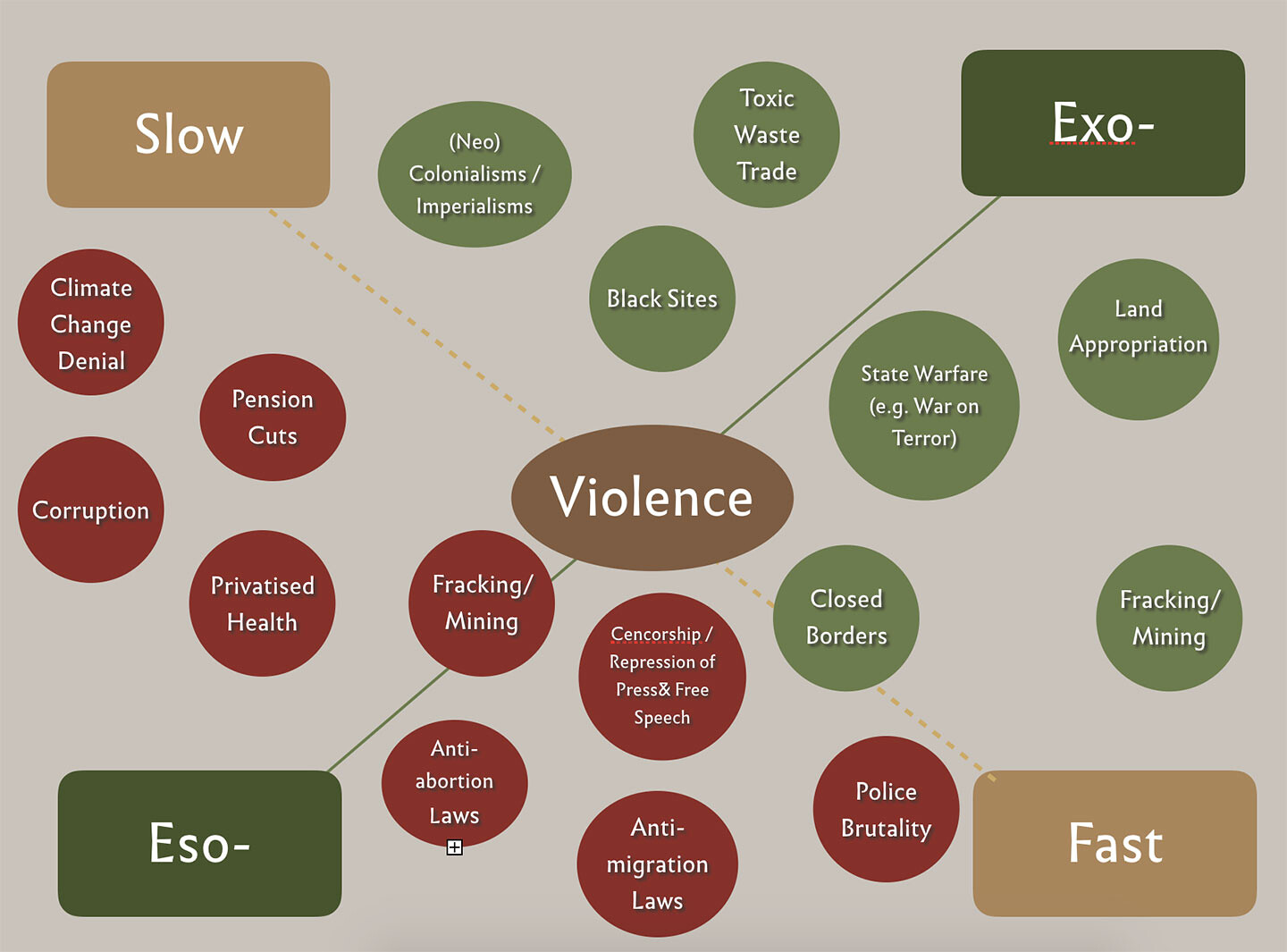

In the second part of this essay, I will examine the mechanisms of narcissistic authoritarian statism through a second axis, that of slow and fast violence. I will then discuss the ways in which the field of contemporary art is entangled in such forms of violence, and will present examples of artistic practices that lay the groundwork for new directions for cultural work.

Diagram by the author.

Narcissistic Authoritarian Statism and Why It’s New

I previously drew on the work of political theorists Nicos Poulantzas and Bob Jessop, primarily Poulantzas’s theory of the state as a relationship of forces, an active organism that is able to metamorphose and transform through power relations. These relations are what define and differentiate the violent aspects of narcissistic authoritarian statism. I engaged a proposition of Jessop’s, adding a fourth element to his definition of the state as composed of territoriality, legitimacy, and violence: the “idea” of the state. Both theorists assist us in understanding the temporal and spatial aspects of a new understanding of the state, enacted through violence. As mentioned in the first part of this essay, we should think of narcissistic authoritarian statism as a pattern, a behavior, and a structure, which is not only recognizable in state formations and their political leaders, but also in institutions and singular actors. Yet this statism is always manifested through violence: a violence that is not simply evinced through direct, momentary acts of aggression but which also has various forms and intensities. Harder to detect and describe are the forms of slow violence perpetrated across vast expanses of time and space. Narcissistic authoritarian statism takes advantage of the slow process of molding identities and realities, redefining violence and its legitimization and cashing in on the effects of neoliberalism.

The difference between narcissistic authoritarian statism and historic instances of autocratic governance is this creation of a new “idea” of what the state considers to be legal and real, constantly performed through a vast spectrum of violent acts. In the words of artist and theorist Jonas Staal, this form of statism is in fact a propaganda machine creating a “new reality.”1 It succeeds because neoliberal subjects have been brought to the point of apathy and detachment, but also a lack of interest in the disenfranchised, vulnerable, dependent, and precarious, an attitude I discussed in the first part of this essay. Since Poulantzas’s early writings on the state in the 1970s, the merging of state and corporate actors, in combination with the increasing power of these corporate actors, specifically in the fields of surveillance technology and social media, has created a new axis, a slow and fast axis, onto which narcissistic authoritarian statism is formed. Globalization has offered an array of examples of slow and fast violence, marked by the scale of operations of a new corporate state. Various scales of violence are perpetrated by multinationals, such as those producing agrochemicals, like Bayer’s subsidiary Monsanto, or mining giants like Glencore, with its mission under the auspice of the IMF in Mexico and Southeast Asia. They are likewise perpetrated by extra-state interventions such as the War on Terror in the United States. The latter, for instance, marked a new chapter in extrastatecraft—to borrow Keller Easterling’s term—where the fabrication of truth and the denial of culpability, together with the arrogance and narcissism of the violent people in power, were followed by complete impunity.

The Slow and Fast Violence of Narcissistic Authoritarian Statism

My concept of scales of violence is informed by Rob Nixon’s book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (2011). In Nixon’s work, “fast violence” refers to violence that is literal, visible, and immediate. In the case of the eso-state (activity conducted within the borders of a state and upon its citizens), one can apply Nixon’s framework to see how the state’s monopoly on violence is manifested in ways such as crackdowns on demonstrations, police brutality, a strong paramilitary that arrests and imprisons, murdering and disappearing dissidents or oppositional politicians and activists, and so on. Fast violence can also be found in the form of a sudden salary or pension cut, instantly affecting the living conditions of individuals. As an example, the immediate effects of such violence were seen during the first years of the financial crisis in my native Greece, where more than two hundred suicides were reported due to sudden debt and foreclosures. Fast violence in the exo-state may take the form of military operations such as those during the War on Terror, or the recent murder of Iranian military leader Qassem Soleimani, ordered without any consideration of the potentially dire regional repercussions and without a strategy, under the guise of national security concerns. There are many examples of overt operations, sanctions imposed on other states, hard diplomacy, the occupation of land for military bases, state-owned multinationals that occupy and extract from territories—so on and so forth. In both eso- and exo- versions, today’s state violence differs from the aggressive acts of previous forms of statism in that it now has two major tools on its side: technology and turbo-capitalism. Denial (and alternative truth) is a large part of its modus operandi.

Since the first notes of this essay were written only a few months ago, there has been a shocking surge of state violence. To consider South America alone: in Ecuador in October 2019, protests prompted by corporate tax cuts and austerity plans led to violent clashes with police forces. Resistance in Chile followed, and the ensuing police crackdown revealed a hidden deep state echoing the Pinochet dictatorship. In Santiago alone, more than two hundred protesters have been deliberately blinded in one eye by police forces. In Colombia, where demonstrations are a daily phenomenon, a woman was seen on video being forced into an unmarked car, during one of the numerous anti-government demonstrations. The country has been racked by riots, triggered by widespread discontent with the proposed economic reforms of the rightwing president, Iván Duque. In my native Greece, the newly elected far-right government has unleashed an extremely violent crackdown on demonstrations, and has sought to destroy all solidarity structures that host refugees. There have been graphic moments of violence such as police officers stripping protesters naked and sexually harassing them—captured in harrowing videos that have gone viral on social media. Since the end of February, when Turkey opened its border to allow refugees to leave the country, Greek police have launched aggressive pushbacks against newly arriving refugees. As I write these lines, two refugees have died after being shot down by border police, while many are endangered in boats that are attacked at sea by the coast guard.2 The fast forms of violence these governments employ go hand in hand with slow violence.

Slow violence as defined by Rob Nixon is

a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all. Violence is customarily conceived as an event or action that is immediate in time, explosive and spectacular in space, and as erupting into instant sensational visibility. We need, I believe, to engage a different kind of violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales.3

Nixon’s focus is mostly on environmental disasters, but this framework opens up a valuable path to recognize other types of undetected slow violence. For instance, consider the propaganda tactics utilized by companies such as Facebook, which slowly permeate the minds of users through targeted ads, manipulating and cajoling, molding societies that hate minorities. Or take the privatization of healthcare in many countries—a system now driven by cost-effectiveness and competition, which limits access to services for those who are financially precarious and which can cause death.4 While perhaps less sensational or visible than physical combat in the street, these forms of slow violence are just as destructive and have longer effects, even creating societies in which more violence of all kinds can proliferate.

Both fast and slow violence are occurring without brows being raised by governmental officials, who claim their legal right (or those of the multinationals they support) to impose violence. These are characteristics of previous authoritarian models, but one new feature of narcissistic authoritarian statism is to make violence difficult to pin on specific perpetrators, through the use of technology and social media to spin new truths and new realities. This, together with the need to generate capital at all costs, has created a new toxic kind of governance infused with classic narcissism: personal disdain and lack of empathy for others, arrogance, and a distorted sense of superiority.

Body and Land versus Religion and Capital

Since 2018 more than forty indigenous leaders have been murdered in the Amazon. Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s denial of the climate crisis (apparent in his claim that the Amazon is solely “Brazilian business”), and his appointment of evangelical preacher Damares Alves as minister of the Cabinet for Indigenous Protection in Brazil, paved the way for mining companies to accelerate the destruction of the Amazon and isolated Amazonian tribes. Just as religion once operated as a justification for colonial crimes, today it is used to justify the violence of narcissistic authoritarian statism. Interpreted by the likes of Bolsonaro as a measure of civilization and salvation, religion is used to explain the infection and murder brought forth by multimillion-dollar mining and meat corporations. Contemporary missionaries can either enact fast violence through murder, or slow violence through preaching the word of the Lord to uncontacted tribes and spreading Western diseases.5 Narcissistic authoritarian statism builds an idea of the state through notions of progress and development, yet these very ideals ironically work against any measures needed to address climate catastrophe—disregarding indigenous communities and creating a new generation of climate refugees. Current states and multinationals narcissistically repackage their operations, claiming they wish to “elevate” indigenous communities from their status as “cavemen,” in the words of Bolsonaro. This may be an old tactic, but it is now done in parallel with the construction of a new reality by demolishing the credibility of science, dismissing scientific facts as lies, and proliferating this information through new technological infrastructures, which Bolsonaro and many other world leaders have done.6

Language is a crucial tool for the narcissistic construction of the corporate state. Throughout the continent of Africa, companies like Lion’s Head Global Partners, with the help of state officials, claim they are “supporting local currency and promoting economic development,” while calling the appropriation of cheap land for the purpose of exploitation “asset management.”7 Sun Biofuels, a Lion’s Head subsidiary that collapsed in 2011, left hundreds of Tanzanians landless, jobless, in despair, and feeling that “this is like the return of colonialism, colonialism in the form of investment,” as noted by Athumani Mkambala, chairman of the Mhaga village in rural Tanzania.8 Sun Biofuels Tanzania declared bankruptcy and never compensated the locals. The company was directed by Christopher Egerton-Warburton, a former Goldman Sachs banker and head of the Lion’s Head subsidiary company Thirty Degrees East, which is based in the tax haven of Mauritius. Such hidden locations of capital accumulation, dispersed around the globe, become necropolitical secret depositories, hiding sinister and unlawful conduct—acts of acute slow and fast violence.

Cultural Workers Against Narcissistic Authoritarian Statism

In 2004, artist Abdel Karim Khalil organized an exhibition in a small Baghdad neighborhood. It was a group exhibition of artists from the area who felt the need to position themselves against what was occurring in the city. The exhibition commented on both the eso-/exo- power of the state and the slow/fast violence Iraqi citizens were subject to daily from both the Americans and Iraqi officials. Khalil’s sculptural installation A Man from Abu Ghraib (2004) is a set of realistic marble figures depicting torture: a visual documentation of a historical moment that disrupted and destroyed a society and a people and initiated a new wave of exiles and refugees. It is one of the rare examples of artistic practice that manages to directly confront eso- and exo-violence, in both its slow and fast forms. The work unearths the violence imposed by the Iraqis and the Americans equally in instantaneous bursts of fast violence during the Gulf Wars, but also throughout the interim periods, during the rise of ISIS and through today. The neo-imperialist arrogance and grandiose illusions of the US military in Iraq and the region contour the narcissism of this type of statism and its violent outbursts.

Another example of art practice that reveals the tropes of narcissistic authoritarian statism is Trevor Paglen’s 2006 series of three photographs of US government “black sites,” which depicts from afar the hidden locations where detainees are tortured by the US state. Nondescript buildings, doors, cars, and guards are seen from a distance. The Black Sites series highlights the beginnings of the War on Terror, when the CIA set up a network of secret prisons in Afghanistan and elsewhere around the world. Undocumented and secret operations, including abductions, torture, and human rights violations against thousands of “ghost prisoners,” occurred for decades behind the walls of secret locations, the details of which were some of the Bush Administration’s most closely guarded secrets. Paglen’s photographs of the buildings are architectural tracings of the violence imposed by the US government, lost in the deep state of classified information. Like Khalil, the work operates as a testimony of forms of fast/slow violence that are not easily traceable. The role of the artist here is to expose, to act as counterintelligence.

In contrast with the Bush era, the narcissism of the US under the leadership of Donald Trump has taken a new turn. In just a few months, through a series of senseless whims, Trump disrupted the already fragile political balance of the Middle East. Equally dumbfounding as, say, the murder of Soleimani in October 2019, was the US withdrawal from Northern Syria and the abandonment of allied Kurdish forces that have been combating ISIS and Daesh for the last five years. On Trump’s Twitter feed and in his public statements, one witnesses the disengaged face of narcissism: “I hope they all do great, we are 7,000 miles away”; “The Kurds are no angels.”9 His actions have sparked outrage from many US citizens, contentment from Vladimir Putin, and approval from another grand narcissist of our time, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Amidst this “bras de faire” shines the work of the Rojava Film Commune, a collective founded in 2015 that works in the region of Northern Syria known as Rojava. For the last four years, the group has been documenting the fast and slow violence of living in a war zone, while simultaneously illustrating the enactment of a new social contract drafted by the Rojavan revolution. Their work stands between cinema, documentary, and political audiovisual testimony and offers not only a glimpse of the violence the Assyrian, Arab, and Kurdish populations have endured, but a glimpse of another vision for living and organizing. The dynamic collective of young filmmakers, established filmmakers, and students seeks to contribute to the development of the revolution by narrating both the history of the struggle and the possibilities it has opened up for the present and the future. As Rojava rebuilds itself politically, the Rojava Film Commune contributes to its cultural reconstruction: through the medium of video and film, the members translate their newfound democratic freedom into a new artistic form. For the Commune, speaking about and showing the histories and culture of the people who have been repressed, persecuted, and killed by the Syrian regime is itself revolutionary. Film here operates as an educational form, but also a tool for imagining a different future. In their work, we see the cultural and artistic equivalent of what it means to self-define, to open a space for—as scholar and theorist Dilar Dirik has said—“living without approval” beyond the patriarchal capitalist state, which Rojavans have rejected. The Rojava Film Commune exposes the real desire behind producing art: to affirm the “living” of life.

Together with the Rojava Film Commune, film collectives such as the Syrian Abounadarra and the Egyptian Mosireen produce a type of “emergency cinema,” in the words of the Abounadarra. Emergency cinema is a type of film work that documents the life of populations forced to endure violence of different speeds and along different spatial axes, for instance during revolution or civil war. Through film these groups aim to construct a counter-narrative to combat this enforced new reality by safeguarding real facts and the silenced realities of millions of people. The time-based and widely distributable medium of film may be a particularly appropriate medium for attempting to describe and tackle violence operating on multiple time scales, often too quick to apprehend or too slow to capture.

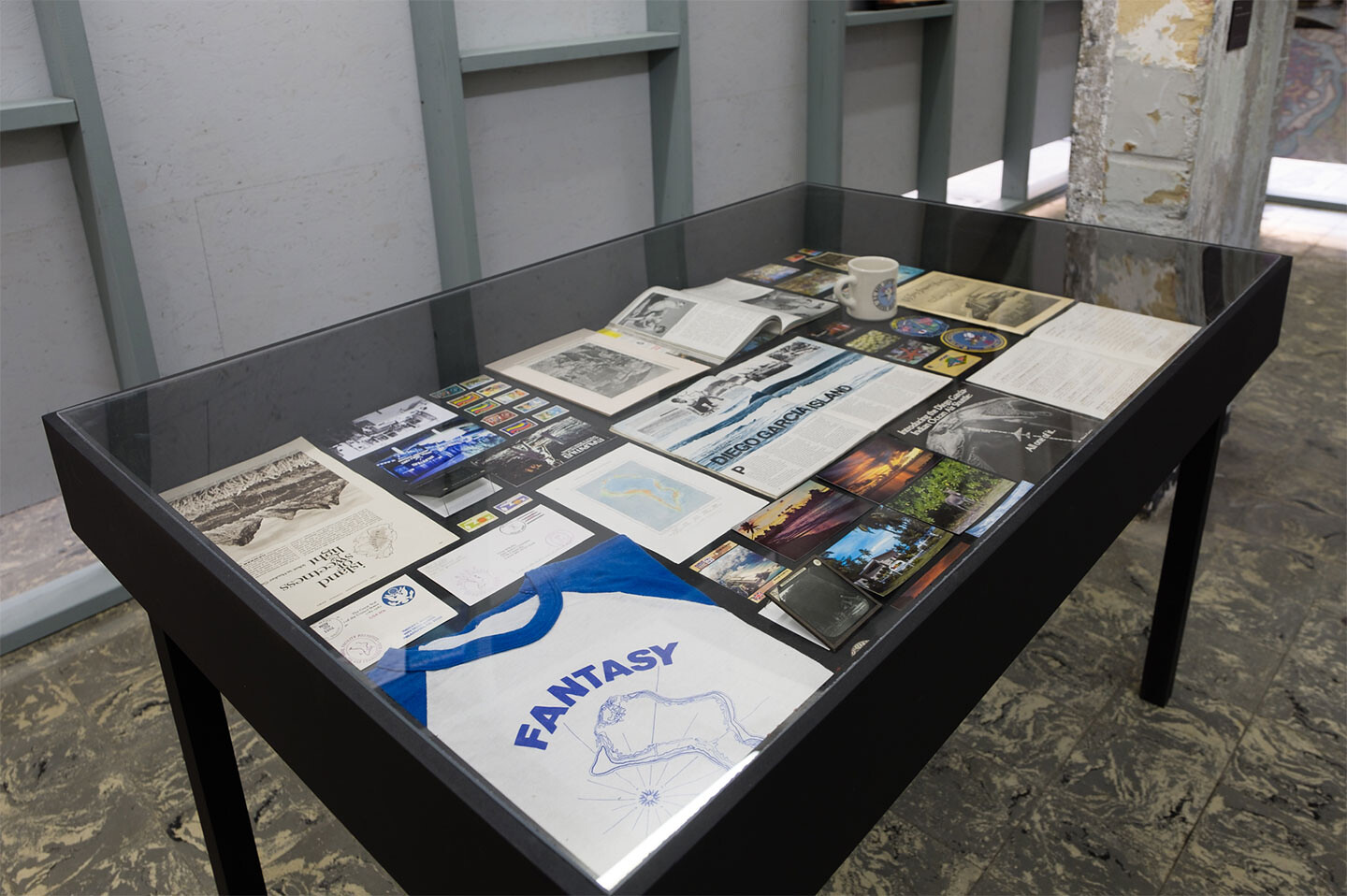

For her 2018 work Foul Footprints, commissioned for the Antwerp exhibition “Extra States,” the Dutch artist Femke Herregraven chose the island of Mauritius as a site to investigate the slow and fast violence inflicted on both land and peoples.10 The installation, which consists of films, wallpaper collage imagery, and three vitrines of objects collected by the artist, reflects on the case of the island of Diego Garcia. Diego Garcia is under the jurisdiction of Mauritius, a country recently in the spotlight for its role in the “Paradise Papers”—over thirteen million documents detailing offshore investment schemes that were made public in 2017. Mauritius is not only a popular location for money laundering, but also a locus of exile. In 1965, just before granting Mauritius its independence, the British government reclaimed one of its island constellations (the Chagos Islands) by renaming it and inventing a new colony. This was orchestrated for the purposes of granting the land to the US in exchange for cheap weapons. The Chagos constellation’s largest island, Diego Garcia, operates today as the US’s largest military base outside US soil. It also happens to be the location from where the War on Terror was launched. The Chagossians are still living as refugees in inhumane conditions in Mauritius, and have taken the UK to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, but the British Parliament claims that the Chagossians cannot live on Diego Garcia because it is uninhabitable due to a lack of water.

But in Herregraven’s work, a collection of US military memorabilia in vitrines and on walls—photographs of soldiers who served there, pamphlets from gyms on the island— proves otherwise. A few months after the work was presented, on February, 25 2019, the ICJ ordered the UK return the islands to the indigenous inhabitants. In May 2019, a UN vote affirmed the verdict of the ICJ, ordering the UK to withdraw its colonial administration and urging the UK “to cooperate with Mauritius in facilitating the resettlement” of the Chagossians. The UK, with its narcissistic authoritarian statism, claims the court never had jurisdiction to hear the case. The violence of the UK continues in the eso-state too: Chagossians who fled to the UK in the sixties and who are British passport holders are today intimidated and urged to leave the country by migration officials—another facet of the Windrush scandal.11

Femke Herregraven, Fool Footprints, 2018. Installation view. Photo by the author.

Cartographies of Slow and Fast Violence: Art as Tool of Justice

Possibly the most complete position and proposition within cultural practice that not only reveals the violence of narcissistic authoritarian statism, but activates the full potential of culture to counteract this type of power, is that of Forensic Architecture. Since 2010, the research agency has been documenting what they call “cartographies of violence,” employing the latest technology to investigate and visualize corrupt judicial systems, failed and authoritarian states, and corporations that bend the law. The group undertakes advanced architectural and media research on behalf of international prosecutors, human rights organizations, and political and environmental justice groups, as well as individual citizens. They have paved the way for a new direction in architecture studies, with the forensics of architecture becoming a new field in academia, now taught at Goldsmiths University in London. The subject matter of Forensic Architecture’s work directly opposes narcissistic authoritarian statism, and so does its effect: drafting a counter-hegemonic power structure that has a tangible impact.

Some of the group’s investigations concern eso-state fast violence, such as the horrific abduction and murder of forty-three students in Ayotzinapa, Mexico by state troopers and paramilitaries on September 26, 2014. Forensic Architecture was commissioned by members of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to provide an account of the events through testimonies, interviews, videos, 3D modelling, data mining, and graphs. They revealed the state as an accomplice to the organized crime groups responsible for the killing, and found that the students’ bodies had been burned in a garbage dump. They exposed the government’s fabrication of facts and discrediting of independent investigative commissions, as well as the blatant disregard and arrogance of local politicians who falsified facts, hid evidence, and produced fake scientific reports—classic traits of the eso-violence of narcissistic authoritarian statism.

In Greece, Forensic Architecture undertook two investigations into the murders of civilians. Here the fast eso-violence of individual actors was accompanied by the slow violence of the eso-state. The first investigation was into the death of Pavlos Fyssas, the anti-fascist rapper murdered on September 18, 2013 in Athens. Fyssas was killed by Giorgos Roupakias, who had been armed by the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn, of which he was a member.12 The increase in popularity of Golden Dawn since the beginning of the financial crisis was facilitated by the Greek police, since many in its ranks have been aligned for decades with its neo-nationalist and neofascist ideology. The investigation revealed that police officers not only delayed responding to the crime, but that they were passive bystanders. The evidence gathered was presented in court, turning cultural practice into a powerful civil-society tool in the fight against a corrupt judicial system.

Unfortunately, narcissistic authoritarian statism has brought new traces of eso- and exo-violence to the cultural field through the ever-growing relationships between its key protagonists and art institutions. This is evident in cases such as that of Warren Kanders, mentioned in the first part of this essay, as well as the Sackler family, longtime art benefactors whose company, Purdue Pharma, is known for manufacturing opioids. In their narcissism, such agents of power apparently feel untouchable and irreplaceable. The initial responses to these cases from institutions revealed the latter’s inability or reluctance to position themselves clearly against funders with dubious backgrounds. It took months of letters, petitions, and collective action for institutions to sever ties. In other words, arts institutions perpetuate a form of violence too.

Fifty years after Greek sculptor Takis removed his sculpture from the Museum of Modern Art and ignited the Art Workers’ Coalition, we still seem to be fighting the same battle. The question that Takis, Hans Haacke, and others asked in 1969—what is the political and social responsibility of the art community?—today seems harder to pose. From my experience, posing such questions in conferences makes colleagues roll their eyes. We are used to praising the “neutral” position of art and the policy of “no politics in the museum.” At the same time, the global art market has grown so much that museums depend on it. And in terms of power structures, museums increasingly model their structures and legislative frameworks on those of corporations.

It is not simply the well-documented effects of neoliberalism’s financial uncertainty, precarity, and joblessness that have silenced culture workers. Worse is the lack of interest in speaking out, due to what Lynne Layton has named “amoral familism, a retreat into an individualistic private sphere and a tendency to extend care only to those in one’s family and immediate intimate circle.”13 We ourselves have been performing narcissistic authoritarian statism on the individual level. The star curators of the 1990s, who have been accused of abuses of power behind closed doors for decades, are examples of this.

What is to be done? In the words of Audre Lorde, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”14 The problem is not only the master, but the house itself. Contemporary art’s house, built on neoliberal individualism, reproduces narcissistic authoritarian statism. “Nuanced” and meek positions vis-à-vis ultranationalism, the alt-right, and neofascism and its aesthetic signifiers promote a theoretical position that seems to deny the very existence of ideology. We thus fail to understand that while the art world desires and imagines itself to be a neutral space, neutrality itself is an ideology—a luxurious fantasy that can only be enjoyed by those who do not feel vulnerable.

Although a renewed focus on identity politics has forced open many conversations, narcissism in the cultural field continues to increase. Afraid to be left off the train of contemporaneity, institutions are addressing diversity, but in entirely superficial ways, reluctant to relinquish any actual power. Thus diversity initiatives are crudely done, tokenizing and creating frictions among individuals with similar struggles, forcing identity politics into dead ends that undermine intersectionality. It is a tactic reminiscent of classic colonialism: divide and conquer.

From the time of the Art Workers’ Coalition to today, we are indeed estranged from the modern promise of an art tied to revolutionary transformation. What we must admit is that this has become, in retrospect, a collective loss. Can we move forward with this modern promise into a future that is less grim? The examples of cultural practices presented in this two-part essay make it possible, I hope, to understand the forms of counter-hegemony that can be found in the realm of art, against the plague of narcissistic authoritarian statism. Cultural practice can still be an act not of only whistleblowing and resistance, but also of reimagining and producing a future form of power, one that remains within our grasp. If we see the role of the cultural worker not simply as an agent provocateur but as an author of counter-narratives, as a creator of new agitprop counter-hegemonies, we can develop a more tangible vision of a new and more just power structure. It is crucial that we as cultural workers become radically aware of our roles and fuctions within and outside (eso- and exo-) the institution, so that we understand exactly what we can do from this position. Refusing to address the dire issues of our time, out of some fear of being singled out or shunned, will lead to more detachment, apathy, and indifference. This is not an adequate response to what might be not only the end of democracy as we know it, but the end of art. We cannot continue to mind our own business and remain silent in the face of violence, in order to maintain our membership in the flock. For under the pretense of neutrality, we hide our complicity.15 The only way out of this poly-axial conundrum of the slow/fast, eso-/exo-violence of narcissistic authoritarian statism is to expose its multifaceted modus operandi, while we propose, imagine, and produce forms of counterpower.

I am finishing this essay in between attending the biggest trial Europe has seen since Nuremberg. It is the trial of the ultranationalist neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn. This trial has been almost forgotten by the international media, and the Greek media, now in line with the new right-wing government, barely mentions it. During these cold days in the Athens Court of Appeals, six lawyers representing the victims of Golden Dawn are aiming to convict the group of an array of crimes—not just as a neo-Nazi party but as a criminal organization. Golden Dawn is being charged with several racist attacks, including the murder of Pavlos Fyssas. As I write, the lawyers are giving their closing statements. One of them, Thanasis Kabayiannis, represents a family of Egyptian fishermen who were attacked on June 12, 2013 in their home by a Golden Dawn squad that broke down their door and smashed their windows, threw teargas in their home, and stabbed them, leaving them for dead. In his closing statement the lawyer said: “Hannah Arendt—whose book on the banality of evil was inspired by the trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann—would have much to say about how easily everyday people can let themselves be instrumentalized as cogs in a machine such as this, either by active participation or silence.”

Postscript: During the editing of this essay, the situation on the border between Greece and Turkey escalated into a humanitarian emergency. While the Erdoğan regime is pushing refugees towards the borders, weaponizing humans in order to force a new refugee deal on Europe, the Greek state has suspended all asylum applications for one month and has established, with the assistance of Frontex, a heavy militarized zone along the border, blocking refugees from entering the country and violently pushing them back. Reports have surfaced that, as of this writing, two refugees have died after being shot with rubber bullets. While the Greek state denies these reports as “fake news and Turkish propaganda,” on March 4 Forensic Architecture released a report demonstrating how Mohammad al-Arab, a Syrian refugee, was indeed fatally wounded by a rubber bullet at the Greek border on March 2. Since then, more reports of violence against refugees have surfaced, while testimonies and videos show paramilitary “patrols” of Greek neo-Nazis and nationalists attacking and “arresting” refugees. German and Swedish neo-Nazis have also travelled to the area and have been seen attacking aid workers, journalists, and refugees. In the last ten days, there have been reports of other attacks on migrants and NGO workers, and arson at refugee aid facilities.

See Jonas Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (MIT Press, 2019).

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2011), 2.

For an analysis of the effects of the privatization of healthcare in the EU, and the marketization of the industry, I suggest one of many excellent articles by Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), a research and campaign group working to expose and challenge the privileged access and influence enjoyed by corporations and their lobbying groups across the EU. See Rachel Tansey, “The Creeping Privatisation of Healthcare,” CEO, June 2, 2017 →.

See “Brazil Accuses US Missionary of Putting Isolated Tribe’s Lives at Risk,” The Guardian, January 23, 2019 →; and “Amazon Gold Miners Invade Indigenous Village in Brazil after its Leader Is Killed,” The Guardian, July 28, 2019 →. In 2018, an American evangelist preacher named John Chau visited North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal, home to the uncontacted indigenous Sentinelese tribe, endangering their lives by exposing them to disease and infection. “My name is John, and I love you and Jesus loves you,” he was reported to have said to them. Chau was not seen again and is presumed to been killed by the tribesmen. See Michael Safi, “American Killed by Isolated Tribe on North Sentinel Island in Andamans,” The Guardian, November 22, 2018 →.

Dom Phillips, “Bolsonaro Declares ‘The Amazon Is Ours’ and Calls Deforestation Data ‘Lies,’” The Guardian, July 19, 2019 →.

From the Lion’s Head website →.

Damian Carrington, “UK Firm’s Failed Biofuel Dream Wrecks Lives of Tanzania Villagers,” The Guardian, October 30, 2011 →.

From Donald Trump’s tweets, October 14, 2019, and a meeting with the Italian President, streamed live on PBS NewsHour, October 16, 2019.

Femke Herregraven, Foul Footprints – No1: Engineering the Island, 2018, commissioned for “Extra States: Nations in Liquidation,” a group exhibition at Kunsthal Extra City, Antwerp, September 2018.

Katie McQue, Mark Townsend, and Katie Armour, “Windrush Scandal Continues as Chagos Islanders Are Pressed to ‘Go Back,’” The Guardian, July 28, 2019 →.

Last year Roupakias grotesquely claimed that “it was just a simple homicide, he literally stepped on my knife, the whole thing is blown out of proportion.” See “Roupakias Describes Fyssas’ Murder as a ‘Simple Homicide,’” Ekathimerini, July 18, 2019 →.

Lynne Layton, Toward a Social Psychoanalysis: Culture, Character, and Normative Unconscious Processes (Routledge, 2020), 180.

Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1984), in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press, 2007), 110–14.

For an excellent analysis on neutrality as complicity, I refer you to a 2017 text by Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman on Trump, the border wall, and architecture →.

Subject

The author would like to thank Laura Raicovich for the discussion about her forthcoming book on cultural institutions and the myth of neutrality; the artist Jonas Staal for his book Propaganda Art in the 21st Century, which informed the propaganda aspect of narcissistic authoritarian statism; and all the comrades in courtrooms and streets, and on screens and pages.