Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, religious radicalism in Russia became associated with political opposition and a search for political alternatives. The ethical tenets of popular faiths often coincided with the aspirations of revolutionaries. The collapse of the USSR ushered in a wave of religious libertarianism. This essay considers three recent exponents: shaman Aleksandr Gabyshev, necromancer Anatoliy Moskvin, and neo-paganist Albert Razin. The main discussion is preceded by a brief historical overview of the subject.

1. Without a Tsar at the Head

In Russia, mass religious dissent is associated first and foremost with the Raskol (Schism). As a result of a series of reforms in the Russian Orthodox Church carried out in the latter half of the seventeenth century, a portion of the population “went into a schism,” i.e., rejected the reforms. A fierce struggle ensued: The schismatics, who saw the ruling power as the kingdom of the Antichrist, fled abroad or to remote regions of the Empire. The regime, in turn, persecuted the dissenters, saddling them with increased taxes, even burning whole villages alive.

After a harsh campaign of suppressing open protests, elites temporarily lost interest in religious dissent. Under the banner of Enlightened Absolutism, Catherine II moved to end all persecution of the schismatics. Furthermore, in 1777, she put out a decree permitting peasants to enroll in the merchant classes. As a result, Raskol, or Old Belief, came to play a pivotal role in the formation of Russian capitalism, which bore unmistakable characteristics of socialism.1 How did this come about?

Old Believers lived in peasant communes. Many aspects of their daily lives, as well as their resources, were collectivized. Communal assets were held in a trust, referred to as obshchak (commons). After 1777, when peasants gained the right to enroll in the merchantry, Old Believer communities saw the opportunity to gain economic independence within a hostile state. The obshchak was invested in a business enterprise, nominally headed by a manager. The state considered this person to be the proprietor, but this was not the case. In this manner, toward the middle of the nineteenth century Raskol became a corporation, injecting into Russian capitalism the ethical principles of a schismatic community.

At about the same time, the state came to suspect a “false bottom” in domestic capitalism, which led to a series of investigative expeditions in the 1840s, led by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Additionally, the government financed several foreign expeditions, notably that of Baron Haxthausen. The latter’s 1843 journey across Russia virtually discovered the peasant commune. Haxthausen, moreover, was one of the first to turn his attention to popular religion and its varieties, in particular Old Belief. He classified religious sects into three categories: 1) those that were formed prior to the Church reforms and that, in his opinion, traced their origins to the Gnostics; 2) schismatic doctrines, arising in the seventeenth century in direct consequence of the Church reforms; and 3) sects coming into existence during the reign of Peter I under the influence of Western religion (Molokans, Dukhobors).2

The results of these investigations shocked the elites. It turned out that the religious beliefs of the common people differed significantly from official Orthodoxy. It was a matter not merely of a pre-reform Orthodox rite, but of a hybrid faith, a folk Orthodoxy, comprising pagan elements as well as collectivist social ideals. The government saw clearly that popular beliefs were perilously close to Western socialist views: universal equality, collective property, and a rejection of state hierarchy. Moreover, it became apparent that official population statistics grossly underestimated the number of Old Believers. In reality, at least a quarter of the population was to a lesser or greater extent schismatic, i.e., held itself in opposition to the central power. This gave rise to new persecutions.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the findings of such government expeditions were made public, ushering in a fashion for Raskol within Russia’s progressive circles. Studies appeared, laying emphasis on the political aspirations of the schismatics. In particular, Afanasiy Shchapov noted that “the shared antagonism of the schismatics toward the Orthodox government and the Orthodox Church united all the schismatics, despite doctrinal differences, into a single brotherhood.”3 Shchapov considered Old Believer networks to form a spatially dispersed oppositional religious confederate republic.

The leading Russian revolutionaries of that time—Aleksandr Herzen, Nikolai Ogarev, and Mikhail Bakunin—made a play for religious dissent. Between 1862 and 1864, Herzen and Ogarev put out a supplement to their periodical Kolokol titled “General Assembly,” aimed at the people, and specifically the Old Believers. At Herzen’s prompting, his associate Vasiliy Kelsiev studied the political potential of the Schism, eventually publishing several volumes of official Russian documents on its history. One of these volumes, dealing with the Skoptsy sect, is preserved in the private library of Karl Marx with his personal notes and marginalia.

The 1860s–70s saw the rise of the Narodnik (Populist) movement in Russia. The radical intelligentsia set out for the provinces to “rouse the masses” against autocracy. The “pilgrimage to the countryfolk” failed in its principal aim, and in the 1880s a disenchantment with Raskol set in. The Populists were replaced by Marxists at the vanguard of the revolutionary movement. The revolutionaries’ attention shifted from the heterodox peasant to the proletariat. At the same time, Marxist organizations continued to pay attention to Raskol. The Bolsheviks in the early twentieth century were particularly interested in religious sects as the most radical forms of society. Within the party, this subject was assigned to Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich. In the 1900s–10s he published “Materials Toward a History and Study of Russian Sectarianism and Schism.” At the second Russian Social Democratic Labor Party congress in 1903, Bonch-Bruevich delivered a paper titled “Schism and Sectarianism in Russia.” In consequence, the party adopted a resolution calling for a social-democratic campaign among the sects, and published nine issues of the monthly leaflet Dawn aimed at the sectarians.

In 1908–10, a faction of the Bolsheviks took an interest in Bogostroitelstvo, or “God-building.” Anatoliy Lunacharsky, Alexander Bogdanov, Maxim Gorky, and Vladimir Bazarov sought to formulate a new religion for the proletariat through a synthesis of socialism and folk religion. In 1909 they organized a school for workers on the island of Capri. The school’s activities and the theoretical writings of the God-builders drew a scornful response from Lenin, who criticized their efforts to create a “proletarian culture” and a “proletarian religion.”

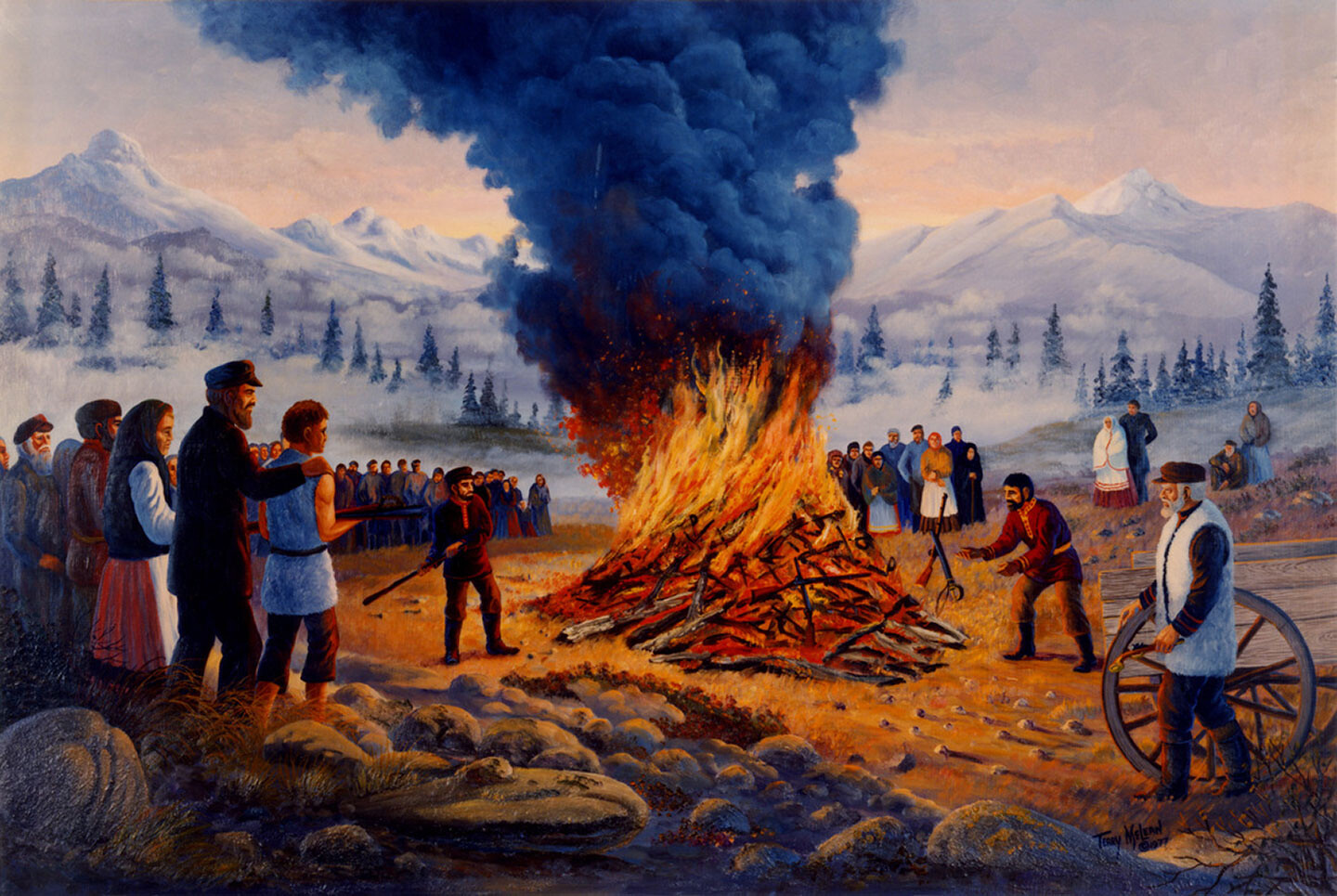

The turn of the century saw an upsurge of interest in the occult, esoteric knowledge, and sectarianism across the spectrum of Russia’s intellectual elite.4 A spiritual radicalization of society was underway. A public campaign to defend the Dukhobors was a case in point. The more radical elements of this sect rejected the principles of compulsory military service, private property, prisons, courts of law, churches, and any other institutions of state power. In 1895, several Dukhobor groups carried out a mass anti-war action: a public burning of weapons. The authorities responded with harsh reprisals. The campaign to defend the Dukhobors was led by Leo Tolstoy and included other prominent figures, such as the anarchist Peter Kropotkin, theater director Leopold Sulerzhitsky, and the Bolshevik Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich. In the end, some eight thousand Dukhobors left Russia in 1898 and resettled in Canada.

By this time the vast domain of religious dissent was understood in somewhat greater detail. It became clear, for example, that some of the Old Believers were Popovtsy (Priested)—harboring oppositional views, but already integrated into the power structure of institutional religion. Besides these, there were various and rather numerous bezpopovskie soglasia (priestless denominations). The latter recognized no hierarchy or formal institutions, and considered all authority, including that of the Popovtsy, to be the rule of the Antichrist. Priestless denominations were quite diverse and continually transforming. Many of them incorporated elements of paganism, comprising a hybrid popular religion, opposed to official Orthodoxy in religious as well as social aspects. In his Writer’s Diary, Fyodor Dostoevsky referred to it as “the people’s Orthodoxy” or the horizontal Church, as opposed to the hierarchical “Orthodoxy of the elites.”

Several of these priestless sects gave rise to radical societies. For example, the Wanderers, also known as the Runaways, rejected all forms of civic duty and permanent residence. The mystical Skoptsy (Eunuchs) practiced castration, while at the same time readily integrating various technological innovations into the life of their community. These came about as a result of what Charles Taylor refers to as the “nova effect,” an intensification of the secularizing processes that began with the arrival of what he calls the “Modern Era” (1500s onwards). According to Taylor, the nova effect emerged at the end of the eighteenth century, bringing about a “galloping pluralism on the spiritual plane.”5 A nonstop proliferation of different forms of spiritual existence results in a situation in which, at a certain historical point, the center of spiritual fulfillment could be displaced outside of church hierarchy, into individual religious experience. In Russia at the end of nineteenth century, the majority of schismatic and sectarian communities shared apocalyptic views, awaiting the end of the existing world order on Judgment Day.

The Russian masses, however, were incapable of arriving at a revolution independently, despite their widespread oppositionist leanings. According to Orlando Figes, this was because the peasantry operated strictly at the level of the community (Mir), rather than that of nation.6 Charles Taylor agrees with him: “Their repertory didn’t include collective actions of this type at this national level; what they could understand was large-scale insurrections, like the Pugachovschina, whose goal was not to take over and replace central power, but to force it to be less malignant and invasive.”7

It was up to the Bolsheviks then to consolidate and transform native libertarianism into nationwide revolutionary events. The party’s prevalent role was certainly well documented in subsequent historiography. Far less attention, however, was given to the various aspects of the popular worldview which made possible the revolutionary experience. After the original studies of the late nineteenth century, we might mention here the Soviet historians Kirill Chistov and, especially, Aleksadnr Klibanov, whose work dealt with popular social utopias and socioreligious movements.8 Soviet historians invariably emphasized the political role of popular freethinking, noting the significance ascribed to it by the classics of Marxist-Leninist thought. They recalled Marx and Lenin’s affinity for the Munster Commune, along with the latter’s statement that “expression of political protest under a religious guise is common to all people at a certain stage in their development.”9

In the post-Soviet period the question was taken up by Aleksandr Pyzhikov. He traced the foundations of the Soviet project to the Old Belief ethics of various priestless denominations, i.e., to the messianic radicalism of the popular faith:

Collective psychology with its Old Belief underpinning became a powerful force that pushed out the old order … The worker and peasant masses literally laid down their bones to prevent the return of the old order of nobility and government bureaucracy (liberal or not), blessed by the Russian Orthodox Church … The new ideology combined the Bolsheviks’ Marxist theory with the communal-collectivist psychology of the lower classes.10

Pyzhikov’s conclusions dovetail with those of the dissident Sovietologist Mikhail Avgursky, who argued that the mass participation of Jews in the October Revolution may be attributed to the sectarian varieties of Judaism and the eschatological messianic sentiments widespread in the community.11

The individualization of spiritual experience intensified over the course of the twentieth century. In the 1960s it entered a new phase, a “spiritual super-nova” according to Charles Taylor, marked by “a generalized culture of ‘authenticity,’ in which people are encouraged to find their own way, discover their own fulfillment.”12 This is the age of expressive individualism. Its advent has coincided with the dismantling of the modern disciplinary society. In Russia it took the form of a critique of the Soviet project and of state-imposed atheism. The USSR in the 1970s saw the emergence of numerous informal intellectual societies engaged in metaphysical, religious, or esoteric pursuits. Even official or semi-official Soviet art of that time bears a noticeable trace of traditionalist metaphysics: one need only recall the films of Tarkovsky, or the neo-traditionalist writers and the “ruralist” painters. Dissident groups assumed a more radical — which often meant more religious—posture. The art of Soviet nonconformists was shot through with a metaphysical strain, which they opposed to the atheist officialdom. The most radical of these groups took up esotericism and occultism, as exemplified by the Yuzhin Group in Moscow in the 1970s.13

Birgit Menzel succinctly sums up the late-Soviet plunge into metaphysics as the “occult underground,”14 while Mikhail Epstein refers to it as the “new sectarianism.” In his work Cries in the New Wilderness, Epstein describes several “sects” among the late-Soviet intelligentsia.15 Although the sects and the writings of their leaders are fictional, the book captured the intellectual climate of those years. As the author states in his introduction, “Any Russian ideology sooner or later turns into a theology … and any social movement, unless it manages to seize power, transforms into a heresy and becomes a sect … In Russia, sectarianism is the preordained means of ‘survival’ of an idea under the tremendous pressure of the state.” In presenting the reader with an assortment of totalitarian heterodox ideologies, the author seeks to obviate the very possibility of totalitarianism: “Our approach to pluralism is different from that of the West—i.e., compromise and moderation of diverging viewpoints. Instead, taking each to its extreme we eliminate the supremacy of one.”16

With the breakdown of the USSR in the 1980s–90s, the country was inundated by a wave of spiritual pluralism. The immediate cause was the abolition of censorship. At the same time, postmodern, critically inclined intellectuals like Mikhail Epstein and the writer Vladimir Sorokin aimed to amplify spiritual pluralism to a radical extreme. For them, this was at once a means of dismantling the repressive Soviet system, a guarantee of pluralism, and a reflection of the peculiarities of Russian culture. Media outlets, freed from the shackles of censorship, were flooded with information about UFOs, extraterrestrials, healers, mediums, Satanists, and all manner of other esoterica. In all, it may well be said that today we are still witnessing an ongoing “occult revival” in post-Soviet Russia.17

Portrait of Anatoly Moskvin. Collage by Alexander Volozhanin as published in Nizhegorodskie Novosti (News of nizhny novgorod), no. 137, 2011. Photo by the author.

2. Recent Instances of Religious Radicalism: From Exorcism in the Name of Popular Rule to Occult Libertarianism

In recent years Russia has seen a handful of high-profile incidents of religious dissent. They were able to draw public interest because in each case an exotic religious stance was intertwined with political statements and/or radical action. Still, assigning the label of “abnormality” to the agent appears to satisfy both the authorities and the public at large. The latter, it seems, refuses to see these incidents as an exaggerated reflection of their own problems.

Let us consider the case of Anatoliy Moskvin, a linguist and Celtologist from Nizhniy Novgorod. In 2011 police discovered twenty-nine life-size dolls in his apartment that were found to contain mummified remains of young girls, aged five to fifteen. Moskvin turned out to be a necromancer, who frequented cemeteries, communing with the spirits of dead girls and digging up their graves. He mummified their remains and turned them into dolls. According to him, with the help of these spirits he was able to access worlds beyond the grave. It was also his intention to resurrect the children in the future, when science discovers the appropriate technology.

An analysis of Moskvin’s beliefs shows that he had synthesized syncretic paganism with gnostic Luciferianism. His communion with the spirits of the dead began in his childhood. Subsequently, through his studies of various pagan traditions—particularly those of the Celts, the Yakuts, and the Mari—he absorbed their views of the afterlife, namely, that contact with the world of the dead may be established through the help of spirits or magic dolls, which these spirits come to inhabit. To be assured of success, one could place something associated with the original host, such as a tuft of hair, inside a doll. Consequently, the items found in his apartment by the police were neither cadavers nor mummies, but magical dolls. Indeed, every shaman possesses a whole stable of magical dolls: they are their principal means of travel between the two worlds.

Besides his paganist views, however, Moskvin was also an adherent of Luciferianism. This worldview is widely encountered in contemporary society. All of it variants extoll three principal values: freedom, knowledge, and power. In the extreme, this means freedom from the shackles of materiality, access to all forbidden knowledge, and power over oneself as the highest form of power. Lucifer (or “light-bearer”) is the Christian analogue of Prometheus: both figures sought to grant man knowledge—i.e., power—and were condemned for this by the gods/God. The type of Luciferianism practiced by Moskvin bore a gnostic, occult character. The knowledge he sought was principally associated with the spirits of the dead. The prospect of resurrection is specifically tied to Luciferianism. Moskvin repeatedly indicated that he felt sorry for the young girls, cut off so early in life. For him they were alive, not dead, because he could hear their restless souls. Moskvin blamed the relatives of the deceased for abandoning their dead: according to him, he merely picked up what others had discarded, when they tossed their dead like trash into the cemetery. Convinced that science will soon master the means of cloning (which is tantamount to resurrection), the necromancer tried to preserve the bodies of the dead girls as best as he could by mummifying their remains with a view to a future resurrection.

The genealogy of Moskvin’s spiritual quest can be traced to the Soviet era. In his essay “Cross without a Victim” (literally “without a crucified one”), Moskvin recalls the prohibition against any discussion of the swastika symbol, and the interest it invariably generated among the intellectual milieu of the 1970s–90s: “It was the lure of the ‘forbidden fruit’ … That time is passed, hopefully for good, and no topic of discussion is off limits to us now.”18 This is an attitude wholly characteristic of the occult underground, where esoteric knowledge is avidly sought out by the “curious.” It is to be dug up in central libraries, and a great deal of time must be sacrificed in its acquisition and subsequent exchange with others “in the know.”

Moskvin is an example of a religious/spiritual libertarian of the right-wing, individualist variety. The individual asserts his right to access any knowledge, regardless of societal or moral taboos. This is libertarianism of the Faustian or Luciferian type. It may also be called “magic libertarianism” or “occult libertarianism”; in any event, it follows a long tradition. Furthermore, Moskvin’s path hews closely to the tradition of metaphysical investigations undertaken by the Soviet intelligentsia, and is a reflection of a burgeoning esoteric culture associated with post-Soviet society. And yet, this same society refuses to comprehend Moskvin’s actions. For the past seven years the necromancer has been subjected to compulsory psychiatric treatment, a form of dehumanization that uses disciplinary methods drawn from the rapidly obsolescing twentieth century, modernist arsenal. Society and the state assert an epistemological rupture on his behalf, thereby showing themselves incapable of self-analysis.

Another example is the act of self-immolation carried out by the Udmurt neo-paganist, scholar, and activist Albert Razin before the Udmurt parliament building in September 2019. Udmurtia is an ethnic republic in the Volga region. The Udmurt people became part of the Muscovy tsardom during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, in no small part as a result of the latter’s expansionist campaigns. Alongside other pagan tribes, the Udmurt people were subjected to forced Christianization under their new rulers, yet managed to retain their pagan traditions to a great extent.

In late-Soviet and post-Soviet periods, the breakdown of disciplinary Soviet atheism gave rise to an ethnic and neo-pagan renaissance among Russia’s various nationalities. The breakup of the USSR functioned in a manner analogous to the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, i.e., as the destruction of the “prison of the nations.”19 For example: the first three national congresses of the Udmurt (Votyak) people took place in 1918–19, while the fourth did not take place until 1991. The national-cultural organization Udmurt Kenesh was founded at that time, with Albert Razin—a well-known and widely respected resident of the republic—among its leadership. Razin urged his compatriots to return to the roots of their pagan religion, proclaimed himself a shaman of the ancient tradition known as tuno, and reconstructed and performed traditional Udmurt pagan rituals.

What was it then that compelled Razin to set himself on fire? It was a law passed in 2018 that removed the obligatory study of national languages across Russia and made it voluntary. The new law prompted a vigorous protest from Razin, who saw in it the return of “Stalin’s policy of Russification.” On September 10, 2019, his one-man protest before the parliament building culminated in self-immolation. Two placards he held in his hands read “If my language should disappear tomorrow, I am ready to die today!” and “Do I have a Fatherland?”

According to various pagan beliefs existing in the area of the Middle Volga basin where Udmurtia is located, self-immolation is a ritual called tipshar. Historically, its practice was fairly widespread among the pagan tribes of this region (Chuvash, Mordva, Udmurt, and Cheremis), as an assertion of one’s right, as personal condemnation of a transgressor who refuses to accept responsibility for his wrongdoing, and finally as a means of punishment, since the soul of anyone who dies an untimely, violent death is unable to find peace and continually plagues the living with a variety of ills. Therefore, to commit tipshar before the enemy’s house is to set upon him one’s vengeful spirit. Justice exacts a high price: the one who commits tipshar deprives his soul of repose. It is an extreme measure resorted to by the powerless and the humiliated in the face of a powerful enemy.

Portrait of Alexandr Gabyshev via the sakhaday.ru website. Photographer unknown.

According to the traditionalist mindset, modern repressions have filled the world with troubled spirits. This is why the world has come to resemble a horror movie. Case in point: the vivid emergence of the Yakut horror film in the post-perestroika era, coinciding with a broad return to shamanic beliefs—both expressions of an ethnic renaissance. As the film Setteeh Sir suggests: this land has been stripped of its tradition, as the NKVD has confiscated the shaman’s tambourine. The couple at the center of the film return to their ancestral Yakut village, largely emptied in the years of Sovietization. They face a succession of difficulties, because the place is filled with ancestral spirits enraged at their progeny. Redemption will not come easy: malignant spirits, wrought by human evil and human error, will not simply go away. In a larger sense, horror is people and ideas driven out of society. The ghoulish corpses and dolls are those whom society has destroyed in its civilizing efforts. This is why Chris Dumas is able to speak of a latent necrophilia in late-modernist society.20 Postcolonial ideologies seek to resolve this problem by advocating for a rehabilitation of beliefs suppressed by the modern age. Similarly, those at the forefront of various ethnic renaissances, like Albert Razin, address the same imbalances. They are religious libertarians, operating at the ethnic, national level. They speak in the name of national-ethnic societies, calling for the liberation of their cultures and beliefs.

The third example is the March on the Kremlin undertaken by the shaman Aleksandr Gabyshev. In August of 2019 Gabyshev set out on foot from the capital of Yakutia, in the northeast corner of Siberia, and headed for Moscow with a mission to exorcise the “powerful demon” in the Kremlin. Once this is accomplished, the people’s rule may finally be established in Russia. Gabyshev considers himself a warrior-shaman, whose orders come directly from God. His is a “double-faith,” or a popular Christianity: i.e., he believes in Jesus Christ, but also in the multitudes of spirits of the traditional animistic religions. This type of religious hybridization is not uncommon in Siberia.

Along the way, Gabyshev’s cause has gradually gained popularity. The plan was to reach Moscow in the spring of 2021 with a large following, which would organically grow up around him in the course of his progress. According to Gabyshev, the entire country is “behind him.” In the Trans-Baikal capital of Chita he spoke at an opposition rally. By the time he reached the Buryat capital Ulan-Ude, Gabyshev was accompanied by a group of several dozen followers. There, his arrival precipitated a wave of oppositional activity.

It was also in Buryatia that Gabyshev and his followers ran into trouble: local “official” shamans of the congregation “Tengeri” denounced him as an impostor. The traffic police confiscated a car that had been donated to the group by supporters. Finally, on September 19, at the border between the Buryat and Irkutsk regions, the shaman was arrested and driven to Yakutsk. There he was charged with publicly inciting extremism, and after a psychiatric evaluation pronounced insane. The criminal charge and the label of insanity exert a double pressure: under Russian law, anyone with a diagnosis of insanity may be involuntarily committed to a psychiatric clinic. The next step is punitive psychiatry: a means of suppressing dissent that is familiar to many Soviet dissidents.

Alexandr Gabyshev during his march to Moscow, Siberia, early summer 2019, via the sakhaday.ru website. Photographer unknown.

Aleksandr Gabyshev does not speak on behalf of the Yakut people. His ultimate goal is a libertarian action at the national level. The reason is that today, religiosity/spirituality is acquiring an increasingly syncretic character, which may be described as post-secular. In Russia this process exhibits some local peculiarities: post-Soviet spirituality inherits from Soviet state-imposed atheism its universalist aspirations, i.e., it is “post-atheistic.” Mikhail Epstein, who coined the term, proposes that whoever finds faith after the desert of atheism is most likely to find faith generally, as the antithesis of unbelief, rather than adhere to a particular confession.21

Another feature peculiar to Russia is the neo-pagan renaissance. Paganism is one of the more obvious choices for those seeking post-Soviet religious emancipation, since it is a system of beliefs that has seen extreme oppression, both under the Russian Empire and in the USSR. Latently, however, Russia has always been far more hybridized than it had officially appeared. On the one hand, popular belief has always been hybridized, incorporating elements of paganism. On the other hand, Soviet Marxism exhibited an affinity for pagan animism in its attitude toward the materiality of the world and spiritualization of matter. “A revival of this whole complex of primeval religions was one of the natural consequences of the Communist project.”22 In this sense, universalist neo-pagan beliefs in Russia are post-atheist squared.

The beliefs of Gabyshev, Moskvin, and Razin are principally neo-pagan. At the same time, they are all hybridized and syncretic, having evolved in the age of expressive individualism. Their religiosity/spirituality is the heterogenous result of inner quests, insights, epiphanies, and experiences. Today the character of religiosity continues to shift from a fellowship of like-minded members of a community toward an individual spiritual path. Or, as Taylor puts it: “Many of these are engaged in assembling their own personal outlook, through a kind of ‘bricolage.’”23

These instances of religious radicalism are composite constructions, therefore difficult to understand, and are readily written off as “abnormalities.” A significant characteristic of this complex religiosity in all three dissimilar instances is their libertarianism, i.e., radical religiosity here serves an emancipatory end. In the case of Aleksandr Gabyshev we are dealing with a libertarian socialism that calls for popular rule and collective action, its ultimate end being the overthrow of state hierarchy. In Razin’s case it is an ethnic emancipation, articulated in nationalistic terms. Moskvin synthesizes a highly individualized version of occult libertarianism. The political and personal aims of these individuals are very different. At the same time, all three have evolved a kind of hybrid and radical religiosity with a powerful libertarian message.

In the age of expressive individualism, religiosity/spirituality takes on a previously unseen syncretism. This, however, should not be taken as a pretext to write off its excesses as abnormal, thereby asserting an epistemological rupture and denying society’s capacity for self-knowledge. On the contrary, all these incidents are excessive manifestations of fundamental processes in the realm of the religious/spiritual today. Moreover, they are part of an important tradition that ties religious dissent to the search for political alternatives. An understanding of these circumstances will serve to displace our perception of the excesses of religious libertarianism from the stigma of pathology toward analytical, hermeneutic, and pragmatic lines of inquiry.

This conclusion is largely grounded in the seminal work of historian Aleksandr Pyzhikov. See his Facets of the Russian Schism: The Secret Role of Old Rite from the Seventeenth Century to 1917 (in Russian) (Kontseptual, 2018).

A. Haxthausen, Studien über die innern Zustände, das Volksleben und insbesondere die ländlichen Einrichtungen Russlands. Translated into English as The Russian Empire: Its People, Institutions and Resources (Chapman & Hall, 1856), 277.

A. L. Shchapov, The Schism of the Russian Old Rite, Considered in Connection with the Internal State of the Russian Church and Civil Society in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Century (1859). Cited in Pyzhukov, Facets of the Russian Schism, 31.

For more information see Aleksandr Etkind, Khlyst: Sects, Literature, and Revolution (in Russian) (NLO 1998).

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Belknap Press, 2007), 300.

Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy (Viking, 1997), 98–101, 518–19.

Taylor, A Secular Age, 259. The “Pugachovschina” was a peasant uprising, led by Yemelian Pugachev, 1773–75. The insurrection united Cossacks, peasants, and various ethnic populations in Russia against autocracy. Most of the several hundred thousand rebels came from the Raskol.

A. I. Klibanov, History of Religious Sectarianism in 1860s Russia (in Russian) (Nauka, 1917); Kirill Chistov, Russian Popular Socio-Utopian Legends, Seventeenth to Eighteenth Century (in Russian) (1967).

V. I. Lenin, Complete Works, vol. 4, 228 (in Russian), as cited in Klibanov, History of Religious Sectarianism, 4.

Aleksandr Pyzhikov, Roots of Stalinist Bolshevism (in Russian) (Argumenty Nedeli, 2018), 530–31.

Aleksandr Agurskiy, The Ideology of National-Bolshevism (in Russian) (YMCA-Press, 1980), 322.

Taylor, A Secular Age, 299.

An informal literary and occultist club, which met at the apartment of writer Yuri Mamleev on Yuzhinsky Street. After Mamleev’s expulsion from the USSR, the group continued its existence into the 1990s. Other prominent members included Evgeniy Golovin, Aleksandr Dugin, Geydar Dzhemal, and Igor Dudinskiy.

In The New Age of Russia: Occult and Esoteric Dimensions, eds. Birgit Menzel, Michael Hagemeister, and Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal (Verlag Otto Sagner, 2012).

Translated into English as Mikhail Epstein, Cries in the New Wilderness: From the Files of the Moscow Institute of Atheism, trans. Eve Adler (Paul Dry Books, 2002), 236.

For Epstein’s introduction in the original Russian, see →.

Birgit Menzel, “The Occult Revival in Russia Today and Its Impact on Literature,” The Harriman Review 16, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 1–14.

Anatoliy Moskvin, “Cross without a Victim,” afterward to Thomas Wilson, The Swastika, tr. Anatoliy Moskvin (in Russian) (Knigi, 2008), 360, 362.

This sense of the word “prison,” initially applied to Russia by Marquis de Custine in the middle of nineteenth century, was later picked up by Russian progressive circles. In 1914 the term was transformed and popularized by Lenin as “the prison of the nations,” aiming to characterize Russian national policy at the time. In the Soviet period it became a kind of cliché referring to tsarist Russia.

Chris Dumas, “Horror and Psychoanalysis. An Introductory Primer,” in A Companion to the Horror Film, ed. Harry M. Benshoff (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014), 21–37.

Mikhail Epstein, Religion after Atheism: New Possibilities of Theology (in Russian) (ACT-Press, 2013).

Epstein, Religion after Atheism, 19.

Taylor, A Secular Age, 515.

Category

Translated from the Russian by Sergey Levchin.