A year before the movie Black Panther is released, 2018, the Seattle Art Museum adds Saya Woolfalk’s installation ChimaTEK: Virtual Chimeric Space to its permanent collection. ChimaTEK imagines a race (or better yet, species) called Empathetics. It is unknown, and maybe unimportant, if they exist in the past or in the future. Nor is it certain if they evolved on planet Earth. What cannot be doubted, however, is the inspiration for the look and cultural mode of the Empathetics. They have a lot in common with traditional West and Southern African art. But like the fictional African state of Wakanda in the comic book and movie Black Panther, the Emphatics’ society is technologically and scientifically advanced in the Western sense. Both the Empathetics and Wakandans have a relationship with nature that’s mediated by highly developed institutions of technical and scientific knowledge. In one sequence of ChimaTEK, which involves blinking avatars that emerge from and dissolve into digital mists, we see lab instruments testing colorful substances.

In Wakanda, there is a lab devoted to improving military equipment and modes of transportation. In both societies—Wakanda and that of the Empathetics—research and development is directed by the public and for the public. In the case of the Empathetics, which is a matriarchal society, the end of any innovation derived from R&D is to enhance the sociality of the community. A new device or chemical substance makes Empathetics more of what they are: empathetic. (Their key governing body is the Institute of Empathy). And so what drives technological development, as a whole, is not the will to domination but the will to a deeper and more interconnected (part animal, part plant) sociality. In Wakanda, which is a patriarchal society, the primary end of the innovations of R&D is protecting the hidden nation’s peace, independence, and prosperity from the colonial and postcolonial powers of the West.

Though the application of technology and science in the Empathetic society (the elimination of want by the deepening of the egalitarian feeling) is very different from that of Wakanda in Black Panther (the elimination of want by military defense), both fictions (or science fictions, or afrofuturist fictions) present a vision of technology that is naive. Both represent technology as an a priori condition of social advancement. We see in the Empathetics’ society, for example, technology already hard at work for the general good. But why does this society need so much science? Do humans really require the latest technology to become more social, more emotional? It seems that a profound connection with others could be achieved with the natural gifts of human sociality: language, cooperative behaviors, innate interdependence.

As for Black Panther, the creators, who are white, claim that the advanced technology of the fictional African nation has as its source a cosmically formed metal called vibranium. It came from outer space. It was delivered to earth by a meteorite ten thousand years ago. The meteor happened to crash in an area in Africa now called Wakanda. Black Africans happened to discover that vibranium had fantastic properties and began mining it not for Europeans but for the benefit of their own society. From this metal sprang the nation’s super-armor, military jets, public-spirited urbanism, and, ultimately, economic affluence. But if the link between vibranium—which must be made of the stuff that all things in the universe are made of—and technological advancement is examined closely, it’s soon revealed to be suspect.

It cannot be doubted that the conventionally liberal-minded creators of Black Panther (Stan Lee and Jack Kirby) had good intentions. They wanted to show blacks in a positive light: black African scientists, engineers, technicians who were as good as (if not better than) white Westerners. But, here is the problem. Western scientific and technological developments, as they are known and experienced today, cannot be separated from the four-hundred-year development of an economic system that places the market at the center of society. We, of course, call this kind of centering (or, to use Karl Polanyi’s language, embeddedness) capitalism. It has caused much misery in the world, but it has also produced an abundance of tools and comforts that the world had never known until its emergence. The Victorians named this kind of history “progress.” It replaced sacred time, which was static or cyclical. Progressive time moves in one direction and never stops promising that a better world is not only possible but also always around the corner. This promise is what keeps progress going.

The intention of Lee and Kirby, as well as Saya Woolfalk (and many other well-meaning afrofuturists), is to humanize black Africans by showing that, by one way or another (profound empathy, cosmic accident, you name it), they have the same capacity for technological and scientific innovation as the white races of the West. But universalizations of this kind (blacks can be technologically advanced, too) are, at the end of the day, more disempowering than empowering. Why?

The important cultural insight is not that black Africans are capable of technological sophistication. There are black Africans in every technical trade and research institute. Affirming the black capacity for technological sophistication and innovation only requires being among black people. It only takes a day of observation to confirm that blacks, wherever they are, can store and distribute cultural information; that their form of learning is, as with all other humans, socially transmitted; and their linguistic virtuosity, in Paolo Virno’s sense, has a Chompskian depth that’s been structured during a long stretch of evolutionary time that’s specific to, and constitutes one of the defining features of, the kind of ape we are. All of these abilities and more, such as cultural innovation, are needed for the accumulation of scientific and technological knowledge.

Saya Woolfalk, Virtual Chimeric Space, 2015 (detail). Mixed media with HD digital video projections. Collection of the Seattle Art Museum. Copyright Saya Woolfalk. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York. According to Seattle Art Museum: “Three Empathics have moved into the museum and established a virtual space where you can step outside your normal, routine self and improve your ability to understand others…”

If the humanity of blacks in Africa or America or Europe cannot be contested (which is indeed the case), then the idea that a black African society obtained its modernity—in the Western sense (the application of technology and science to the everyday materials of production and consumption)—from something that literally fell out of the sky is just insulting. However, the idea that this kind of modernity was obtained by the sheer force of fellow feeling, as with the Empathetics, has something to it. It does correctly identify one of the key features (empathy, being mindful of others) of human ultra-sociality, from which our hyper-culture (social learning) emerges. And as such an emergence, it sets into motion a system of “compossibiles”1 that enhance the transmission from the virtual (the felt) to the real (concrete practices)—the cooperative behaviors that any mode of advancement (in this case, science and technology) depends on. That said, Woolfalk’s afrofuturism still reads progress as cyclical. For the Emphatics, there is no break between sacred time and progressive time, and this absence of a break is baffling or even a mystification. The achievement of a high degree of technological development is not possible without a notion of time that moves in one direction, that moves forward.

To explain how this is so, we need to turn to the defining contributions that Moishe Postone made to late-twentieth-century Marxian theory in his book Time, Labor, and Social Domination. In this work, published in 1993 (a very bleak period for Marxism), he makes two important claims. One is that labor, as analyzed in Karl Marx’s Capital, Vol. 1 and the Grundrisse, does not ultimately lead to a way out of capitalism but is instead constituted by it, and as such is a necessary component of value, which, unlike use value, has nothing to do with material wealth (it is indeed immaterial—not one atom can be found in it) but instead is a conceptual construction of what’s generally required to maintain a form of growth that has no end in sight.

Two is that capitalist temporality is not universal but a specific historical formation that has its origins in seventeenth-century2 Europe and is composed of two dimensions. One dimension is totally abstract (or conceptual) and has the appearance of the Newtonian3 absolute—a homogeneous time that extends infinitely in both directions and contains everyday experience such as working hours (9 to 5).4 For the realization of surplus value, this historically determined homogeneous time must be sustained or redetermined by the concrete dimension, the activities in the lived world. The tight relationship between abstract time (which is experienced as concrete time) and concrete labor (which is valued as abstract labor) is that the latter determines the status of value as a whole—how it falls or rises. The former, value as measured by time, as the devil would have it, never changes. But the activities of concrete labor must (indeed are condemned to) accelerate; they cannot remain constant (that would result in a form of socialism that approximates the one Keynes had in mind in his General Theory). Surplus labor can only be extracted in the context of fixed Newtonian time, but productivity (the output of stuff) is not tied to this time; it determines the content of fixed time. What you make in an hour can change, but not the hour. And it is here we have the source of the main form of surplus value, which is relative surplus value—it becomes decisive the moment the working day is fixed.

Increased productivity only redetermines what is contained in a Newtonian or absolute time. For example, in the past, twelve people were needed to produce one product in one hour. Today, it can be done by one person. This does not change the hour as value, but it does change the hour as fixed to what Marx, according to Postone, calls “socially necessary labor.” And what determines socially necessary labor is not what common sense understands as the human/environmental metabolic processes (resources in/waste out), but what a given group in a given time defines—against the background of its own historical developments—as the most basic needs specific to that group.5

If this theoretical frame, elaborated by Postone, explains a lot of the world we see around us (and I believe it does), then we must reach the further conclusion that what Postone, and Marx, call socially necessary labor is better defined as culturally necessary labor. A Marxism of the future will certainly need a clear distinction between the social and the cultural.6

The hardest thing to grasp in all of this is that value is entirely cultural. It seems obvious to see it as a relationship between humans and nature (or what Marx calls social metabolism, or “stuff transformation”—Stoffwechsel), and to see as obscure what a Marxian analysis reveals it to be: a relationship between humans mediated by value. But value (or abstract labor, or abstract time) is cultural, whereas use value (stuff produced by concrete labor, concrete time), is, ultimately, social.7

The advantage of this distinction is that it reinforces Postone’s claim that capitalist history is not universal but confined to a specific set of factors that are historically constructed. The properties of capitalism aren’t, to use Postone’s favored word, transhistorical. The social, however, is transhistorical, and also trans-species.8 A life-form can be social without being at all cultural. The same is not true the other way around. Culture needs a high degree of animal sociality. It is the stage toward the full realization of the symbolic. Culture is the level at which much of what an animal thinks can be completely delinked from the iconic and the indexical.

The cultural as purely symbolic presents the possibility for misreading a capitalist system (a cultural construction) of production and distribution as entirely referring to the satisfaction of human needs by the appropriation of the resources in nature. The ant forages. The human has factories and shops. They are one and the same thing. But the ant is obviously in the realm of social labor. A human is not. A large part of what constitutes human needs in a given community is in the realm of the symbolic.

But here is Postone’s great contribution to Marxian theory, and what must force us to reconsider what technological development is in essence. The linked dimensions of fixed Newtonian time and concrete activity (or capitalist productivity) results in a dynamic that must be considered by afrofuturists like Saya Woolfalk and Ryan Coogler, the director of Black Panther. Capitalism, as described by Postone, is what actually motors rapid and linear technological advancement. This is your progress. Technological advancement is not a given (or a convergence) unless we assume that capitalism is a given, which it is not. Without capitalism, and its form of historical development, which is specific to it (meaning that it’s not universal), you would not have technological advancement as we understand it.

What we mostly find in the historical record is a pattern of ideas or tools or forms of organization that mediate human social metabolism appearing and disappearing, or simply persisting without improvement for thousands of years. Before the scientific revolution of the sixteenth century, the ideas of an ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, dominated thought in the Islamic and European worlds. The West did not fully break from that deep past until very recently (the nineteenth century). What’s normal, according to the historic record, are intellectual and technological developments that begin, thrive, and just die. Dark ages are all over history. What happened in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire wasn’t exceptional.

This is one of the key ideas presented by Postone. He registered a connection between Marx’s mature theory of capitalist value and Hegel’s Subject. Whereas the latter philosopher saw this Subject as the self-realizing and autonomous spirit of history that has as its goal the final synthesis of the world (the objective) and the individual (the subjective), Marx saw in Hegel’s Logic of the Concept an excellent description of capital. The logic of the market is presented to its subjects (the workers and the owners of the means of production) as an unfolding that’s completely independent and self-motivated.

This is how Postone puts it:

[In his] effort to grasp the peculiar nature of social relations in capitalism, Marx analyzes the social validity for capitalist society of precisely those idealist Hegelian concepts which he earlier condemned as mystified inversions … Marx suggests that a historical Subject in the Hegelian sense does indeed exist in capitalism … His analysis suggests that the social relations that characterised capitalism are of a very peculiar sort—they possess the attributes that Hegel accorded to Geist. It is in this sense, then, that a historical Subject as conceived by Hegel exists in capitalism.9

Again: technological development is not a given. There is nothing universal about it. It happens sometimes. It does not happen other times. Sustained and rapid technological development is only found in the culture of capitalism (a mode of economic life that’s not at all old). This market-mode drives history forward for the purpose of capturing, within a culturally constructed Newtonian time-space, relative surplus value (the hours of work that are not rewarded). The hour itself does not change, but productivity does. And this dynamic, which Postone describes as a treadmill,10 pushes history forward.

Postone makes the matter plain in this passage:

The dialectic of the two dimensions of labor in capitalism, then, can also be understood temporally, as a dialectic of two forms of time. As we have seen, the dialectic of concrete and abstract labor results in an intrinsic dynamic characterized by a peculiar treadmill pattern. Because each new level of productivity is redetermined as a new base level, this dynamic tends to become ongoing and is marked by ever-increasing levels of productivity. Considered temporally, this intrinsic dynamic of capital, with its treadmill pattern, entails an ongoing directional movement of time, a “flow of history.” In other words, the mode of concrete time we are examining can be considered historical time, as constituted in capitalist society.11

If this passage is read closely, and if the record of human history is examined widely, we begin to see our times as specific. Furthermore, Hegel, a subject of capitalism himself,12 apparently confused historical developments specific to capitalism with developments that are transhistorical—his idea of the World Spirit, the self-moving Subject, the Concept, the Objective Spirit. This misidentification is not made very clear if one refers solely to Hegel’s Science of Logic, as Postone, Chris Arthur, and the contributors to the otherwise excellent volume Marx’s Capital and Hegel’s Logic: A Reexamination (edited by Fred Moseley and Tony Smith) do. (The misidentification is more apparent in Hegel’s lectures in the Philosophy of History.)

This idea that the whole of human history is moving forward, advancing, improving, progressing from the Asiatics to the German desk owned by none other than Hegel himself, is the philosopher mixing up capitalist society with all of human history. There is no unfolding Geist. There is only, at a particular place and time, the unfolding of this very new thing called capital.

As I pointed out earlier, the white creators of Black Panther claimed that the advanced technology of the fictional African country had as its source a metal called vibranium. From this metal sprang the nation’s super-clothes, jets, advanced weapons systems, and economic affluence. But, in the light of Hegel’s mix-up, and Postone’s reading of Marx, we can see that the noble effort to humanize black Africans through the creation of a fictional society that’s technologically advanced only mystifies capitalism—an economic system that does not owe its rapid scientific and technological progress to something that fell from the sky or was found in a cave that opened after an earthquake. Capitalism moves forward in a time of its own making; and the dynamic of this movement is a value that is immaterial and remains the same as the materials of production and consumption are constantly revolutionized to claim, for a period of time, relative surplus value.

This is very important to understand. Capitalist value is abstract and fixed, and the profits of corporations and bankers are made by repeatedly changing (revolutionizing) what counts as culturally necessary labor. This is the culturally determined time that’s needed in order to produce commodities. To get an idea of what this means, let’s imagine the beautiful spears of Wakanda. If the society’s progress was determined by capitalist value (rather than a mysterious substance from space), then we would assume there must be spear factories in Wakanda. We can also imagine these factories are in competition. The owner or owners of each factory want to claim a larger and larger share of the spear market. Now, let’s say that, in general, it takes one hour for a factory to make a Wakanda spear. If a spear entrepreneur wants to get ahead of his or her competitors, they are forced to increase the output of their product somehow.

With the assistance of a brilliant Wakandan engineer (let’s say T’Challa’s sister Shuri), one entrepreneur develops a process that can manufacture two spears in one hour. This advancement will shake up the whole spear industry because this entrepreneur can do in one hour what the others do in two. This advantage and its market consequences has a name. It’s called relative surplus value.

What happens next? The factory that makes two spears in one hour moves forward in time; that is where the extra value is. It moves toward a society that has yet to exist. This society does not have as yet its culturally necessary labor time set to two spears in one hour. This factory is then, for a moment, the future of its culture. But eventually, the other spear entrepreneurs figure out how to make two spears in one hour, and so two spears in one hour becomes the new culturally necessary labor time. Then one day, an entrepreneur applies some science to spear production. This new kind of spear can fire beams of concentrated energy. All the warriors want this spear. The market is shaken up again. For a time, the entrepreneur enjoys relative surplus value, but from the consumer end of the market.

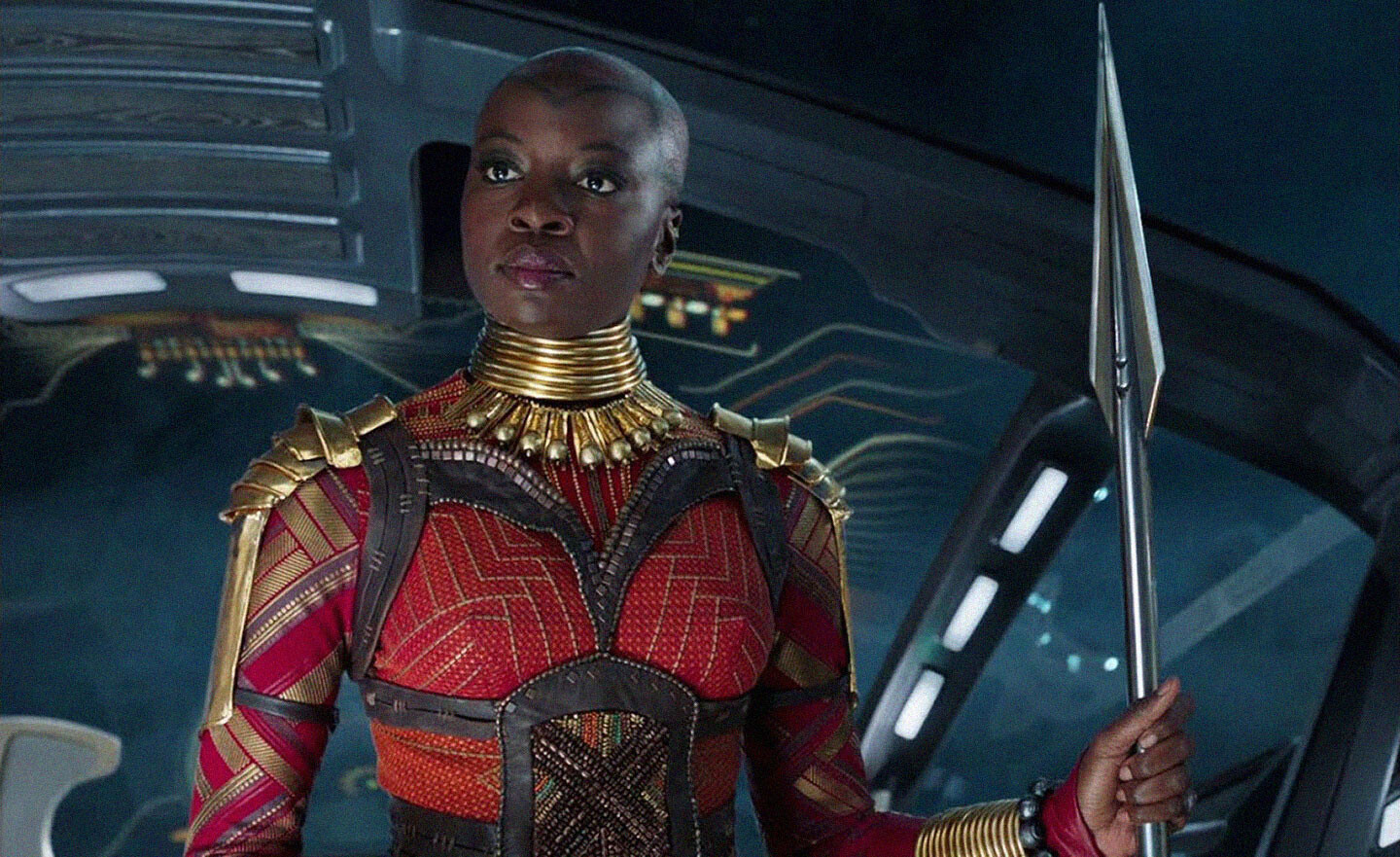

“The production of a Wakanda spear in a capitalist society.” Film still from the Marvel movie, directed by Ryan Coogler, Black Panther (2018).

If these images are properly grasped, then we must not only examine and critique the visions of Wakanda in the historically specific context of capitalist value-driven development, but the future as represented in afrofuturism as a whole. The future, in capitalism, is not utopian or a better world (even a quick examination of the products this system generates reveals this fact). It is nothing but the time of the most profits; or put another way, it is future-time surplus value made present. And the disruption characteristic of this future of increased productivity condemns whatever is present to the past. Commodified history is a movement forward that must not be confused with universal history. Machines that make two spears in two hours are sent to Wakanda’s scrap heaps.

How do we escape this trap of the movement that, in essence, is not really a movement? For Postone, it is the recognition of labor’s central role in the constitution of capitalism’s progressive history. It is not a matter of liberating labor and permitting it to flourish. It’s the abolition of labor as organized not so much by abstract time but by abstract value, which determines and intensifies concrete labor, the source of material wealth.13 According to his reading, which was influenced by the collapse of the Soviet experiment in 1989 and the challenges that Marxist critical theory faced from post-structuralists, particularly, Michel Foucault, who offered a non-Marxist interpretation of historical developments (in the terms of a Nietzschean genealogy), we keep seeing all of these opportunities for life outside of capitalism that, again and again, turn out to be not only inside of capitalism but reconstituting it. The appearance of an outside is indeed needed to move the system forward. It cannot reconstitute value unless, by innovations in technology or science or organization, it redefines what constitutes culturally necessary labor within the fixed hour of absolute Newtonian time.

I want to end by considering two Biblical angels of death. One is Azrael and the other is Abaddon. A theory of liberation from capitalist modernity, as described by Postone, will need to see these death angels as different. One, Azrael, is the angel of renewal; Abaddon is the angel of the abyss. The former transforms an end into a new beginning. He does not destroy the past and the future at once. The future not only remains but is revitalized. In capitalism, what we often see as a liberation from the past turns out to be Azrael. This angel perpetually renews, reconstitutes, and pushes capitalism into the future. With Azrael, the new becomes the same, again and again. Here we have an angel of death who never leaves Postone’s treadmill.

Abaddon, the angel of the abyss, is the one that truly brings things to an end. Whatever he destroys cannot become again. This angel breaks the treadmill of progress. Yet, this angel cannot be found in the worlds of the Empathetics and Wakanda. These worlds are all about Azrael.

The metaphysics of seventeenth-century philosopher and courtier Gottfried Leibniz maintained that the world we live in is the best of all possible worlds because God realized a world with the greatest number of mutually compatible possibilities. And so, for a possibility to efficiently become real, it must be compossible—in agreement with other possibles. He wrote in the brief piece “A Resume of Metaphysics” that from “the conflict of all possibles demanding existence this at least follows, that there exists that series of things through which the greatest amount exists, that is, the maximal series of all possibles.” Compossibles are what determine what can pass easily into the reality of a given culture.

I’m on the side of Marxist theorists who recognize the Dutch Golden Age as the birth of capitalism. Thinkers like the late Ellen Meiksins Wood marked its starting point in eighteenth-century rural England.

Moishe Postone’s use of Newtonian time to explain capitalist temporality might fruitfully be compared with David Harvey’s Newtonian space. In the 2004 paper “Space as Keyword,” Harvey organized space into three types: 1) absolute, which is fixed, Newtonian, and represents “the space of private property and other bounded territorial designations (such as states, administrative units, city plans and urban grids)”; 2) relative, which is Einsteinian, and concerns the movement of commodities; it is “the space of transportation relations”; and finally 3) relational, which is Liebnizian and collapses Einsteinian space-time into monadian internal relations—“external influences get internalized in specific processes or things through time.” From the perspective of economics, the first space represents classical liberalism, the second the neoclassical moment (which includes Keynesianism, or at least its bastard form, as Joan Robinson put it), and the third neoliberalism. See David Harvey: A Critical Reader, eds. Noel Castree and Derek Gregory (Blackwell, 2006), 270–95.

Dolly Parton: “Workin’ 9 to 5, what a way to make a livin’ / Barely gettin’ by, it’s all takin’ and no givin’ / They just use your mind and they never give you credit / It’s enough to drive you crazy if you let it! / 9 to 5, for service and devotion / You would think that I would deserve a fat promotion / Want to move ahead but the boss won’t seem to let me / I swear sometimes that man is out to get me!” From the album 9 to 5 and Odd Jobs (1980) →.

This point was made by Adam Smith in Book 5, chapter 2 of An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. He writes: “By necessaries I understand, not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life, but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without. A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessary of life … But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt … Custom, in the same manner, has rendered leather shoes a necessary of life in England. The poorest creditable person of either sex would be ashamed to appear in public without them … Under necessaries, therefore, I comprehend, not only those things which nature, but those things which the established rules of decency have rendered necessary to the lowest rank of people” →.

It’s important to keep in mind that a high-degree of sociality (or hyper-sociality) does not always result in a sophisticated or complex culture (or ultra-culture). Ants, for example, are highly social, but they don’t have much of a culture. This point is made in an important 2018 book by Gary Tomlison, Culture and the Course of Human Evolution. But there is a reason I emphasize the difference between culture and the social. The confusion of the two leads to attributing what is transhistorical (the human as a social animal) with that which is historical, and therefore plastic or can change quickly (the human as a cultural animal). It is at this point that my own theory (which draws from sociobiology) meets Postone’s post-Marxian assertion of the historical specificity of capitalism.

Value is purely cultural, and use value is part cultural and part social. In his 1973 book The Mirror of Production, Jean Baudrillard argued that both value and use value were cultural. This insistence was inspired by his very loud break with orthodox Marxism.

Gary Tomlinson writes: “What are the general differences between the semiosis that is widespread in the animal world and the much rarer elaboration of semiosis that constitutes culture? What are the features that have enabled a few animal taxa to elaborate semiosis into culture? Such questions can easily exhaust themselves in debates about the extent of animal culture in the world today. These are of immense inherent interest, of course, and they have greatly raised our awareness of the complexities of nonhuman animal behaviors. They suggest that we should draw the borders of nonhuman culture liberally, to include at least a small range of mammalian and avian lineages: certain primates, some cetaceans, a few other mammals, and some birds. All the same, we must be careful not to confuse animal culture with the far broader category of animal sociality. Ants have complex societies, but they do not have cultures. Many instances of highly developed avian and mammalian sociality also exist without giving rise to culture.” Gary Tomlinson, Culture and the Course of Human Evolution (University of Chicago Press, 2018), 79.

Moishe Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 74.

Postone writes: “The reconstitution of value and the redetermination of social productivity entailed by the dialectic I have outlined are the most basic determinations of a process of reproducing the relation of wage labor and capital which is both static and dynamic; this relation is reproduced in a way that transforms each of its terms. This process of reproduction, as analyzed by Marx, ultimately is a function of the value form and would not be the case were material wealth the defining form of wealth. It is, as we have seen, an aspect of a necessary treadmill dynamic, in which increased productivity results neither in a corresponding increase in social wealth nor in a corresponding decrease in labor time, but in the constitution of a new base level of productivity—which leads to still further increases in productivity.” Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination, 347.

Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination, 293.

Hegel was one of the first philosophers to recognize capitalism. But he did not name it as such. In his 1803 text “System of Ethical Life,” parts of which appeared in his mature work Philosophy of Right, he vividly describes a capitalism that’s so developed that much of it can’t be distinguished from the capitalism of our day.

The separation of wealth as value from wealth as stuff results in what John Maynard Keynes described in his General Theory as “poverty in the midst of plenty.” For more on this, read Geoff Mann’s “Poverty in the Midst of Plenty: Unemployment, Liquidity, and Keynes’s Scarcity Theory of Capital,” Critical Historical Studies 2, no. 1 (Fall 2015).