What if we consider tear gas as the exemplary medium of climate emergency, which environmentalist organizations are calling on governments worldwide to urgently recognize? We’d face an entirely different politico-ecological calculus than carbon’s, referencing not only a regime of socioeconomic inequality, but explicit repression and violence, too. Compared to greenhouse gases’ usual suspects—carbon dioxide, methane (dubbed “freedom gas” recently in the US1), nitrous oxide, and hydrofluorocarbons—on which climate emergency groups like Extinction Rebellion (XR) focus, the chemical weapon more directly exposes the nefarious side of global capital and thus leads immediately to an entirely different political analysis. Its toxic environment defines a conflicted war zone where unauthorized challenges to the ruling order—an order that is itself bringing about climate chaos, profound inequality, and systemic violence—are met with the weaponization of air, a formulation that proposes a very different way to consider the reality behind the otherwise banal phraseology of “climate change.” As we’re now seeing all over the world, counterinsurgency increasingly answers popular sovereignty demands in the age of post-democratic and ecological breakdown, indexed by an authoritarian atmospherics, a militarized ecology, of strategically enforced climate control. At the same time, these attempts are directed at forces that are ultimately uncontrollable.

The recent mass uprisings in Hong Kong; the anti-colonial rage expressed on the streets of San Juan; uprisings in war-torn Iraq; anti-neoliberal revolts in Chile; Central American migrants fleeing agricultural failure and gang violence crossing the US–Mexico border zone—all have been answered with tear gas, an integral component in the liberal-become-authoritarian state’s response to opposition that bypasses conventional routes of negotiation. Its (supposedly) nonlethal crowd control is clearly post-political, maintaining the state’s monopoly on violence. Nonetheless, these worldwide revolutions rise up against everything tear gas represents, and it is these struggles that can offer important lessons for the politics of climate emergency, beginning with a necessary expansion of our terminology.

With atmospheric carbon, conversely, the source is vastly distributed, rendering environmentalist demands and science’s politics complex and inarticulate, with causality and culpability hard to ascertain. Sure, there are powerful fossil-fuel corporations, and devious backroom lobbyists, but are we not also all carbon subjects, thoroughly enmeshed in an interconnected web of consumer complicity and guilt? So we often hear, even though we know that the wealthiest emit the largest share by far. With tear gas, the enemy is clear: Safariland CEO Warren B. Kanders, for instance, ousted recently from the Whitney Museum’s Board of Trustees after sustained mass protests around the so-called “Teargas Biennial,” his weapons profiteering seen as complicit in police actions against Black Lives Matter in Ferguson, migrants at the US–Mexico border, Turkish pro-democracy activists in Gezi park, and Gazans opposing Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands. Safariland’s Triple Chaser tear gas grenades—and the institutions that support and enable its use—bear a clearer signature of repressive order than fossil fuels more generally, even while the two remain intimately intertwined, with energy, infrastructure, and security all essential components of the petro-capitalist complex.

Of course, there is also glyphosate, micropolymers, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, neonicotinoids, chlorpyrifos, and more—all enacting untold damage, and for massive profits (Safariland has had annual revenues of $500 million in recent years). There are bullets too, the kind that have killed 164 environmentalists this year alone, according to Global Witness.2 Guns join white-supremacist violence and anti-immigrant racism, as in Christchurch and El Paso, resulting in what Naomi Klein terms “climate barbarism,” the repressive state and the lone shooter two distinct positions on its spectrum.3 One can and should perform a critical analysis of all of them—and their systemic interconnectivity—but tear gas has gained particular visibility as of late as one key element of climate barbarism. Yet for many environmentalists, it remains invisible, and this is a strategic error.

For Extinction Rebellion, climate emergency threatens civilizational collapse, attributed most immediately—and tellingly—to atmospheric carbon. Indeed there are fewer than twelve years to act, we’re told (in a recent IPCC science report4), before cascading tipping points of multispecies disaster overtake all. The human die-off—a massive population “correction” for a contracting biosphere of habitat destruction, desertification, and drought—could number billions in the next eighty years (the crash owing to shrinking resources, failing agribusiness, and consequent resource wars).5 This alone legitimates XR’s macabre funereal obsessions, a prefigurative aesthetics of emergency overflowing into the streets, a recognition too that institutional containment of the becoming-activist of creative expression, of the structural transformation of collective practice in the era of emergency, is increasingly impossible in these circumstances. The sense of urgency driving multitudes to action all over the world is surely inspiring, but also potentially misdirected. But rather than dismissing the movement, let’s contribute to this growing energy so that it foregrounds a just transition—meaning a radical restructuring of our politics and economics by prioritizing equality, social justice, and multispecies flourishing—rather than another depoliticized, single-issue environmental initiative, or worse, part of the growing project of green neoliberalism. To do so, a change of focus is necessary.

***

XR demands that governments “tell the truth” about climate emergency, “act now” to decarbonize by 2025, and become “beyond political” by empowering “citizens assemblies” to enact climate justice. “We live in a toxic system, but no one individual is to blame,” they claim, completely bypassing the justice-oriented arguments and historical gains of such groups as Black Lives Matter UK, Indigenous Environmental Network, Global Grassroots Justice Alliance, and the Climate Justice Alliance, which have long highlighted the racial and class-based inequalities of differentiated climate disruption.6 With XR activists blockading intersections, performing mass die-ins, and gluing themselves to government buildings and corporate headquarters to those ends—where collective interventions shut down institutions of normalization denying emergency in the first place—the radical means often miss such a political analysis (what is the “beyond” of the political, if not deluded liberalism?). This situation is made only more difficult by narrowly focusing on carbon as the cause of emergency.

In its gloomy pantomimes, XR performs the death of the future—but it’s a funeral without a body. Its macabre forms, reminiscent of Atwoodian dystopian SF, risk surrender to fatalism, even as they riff on ACT UP political funerals in expressing emotions for the loss of more-than-humans and coming environmental catastrophe. With ACT UP, “mourning became militancy” precisely because death (of community members and loved ones) and the dead (sometimes presented in public funerals) were not naturalized through the epidemic and thereby depoliticized (as when 350.org’s Bill McKibben explains we’re at war with “climate change,”7 rather than petro-capitalist violence). Rather, the HIV/AIDS epidemic was understood as political insofar as it was seen as the murderous result of politicians’ homophobia, media sensationalism, and pharmaceutical profiteering.8 XR’s funerals, by contrast, risk naturalizing climate, mourning a coming abstraction—not because it’s not real, but rather because XR fails to identify meaningful causes in Western modernity’s political and economic order, consequently emptying activist rituals of any traction. XR universalizes causality in the generalized “we” of “human activities” (as in its statement on “The Emergency”9), much like the “beyond political” species-being of neo-humanist Anthropocene discourse. Moreover, by situating emergency in the near future, and by narrowly defining it as carbon caused, it’s as if the disaster hasn’t already occurred—in past invasions, slaveries, genocides, all perpetuated in ongoing land grabs, displacements, and extractivism, as the traditions of the oppressed have ceaselessly shown. Indeed, indigenous activists remind us that they are already “post-apocalyptic,” and have already lived through exactly the socio-environmental breakdown now predicted by climate scientists.10

In this regard, XR’s mourning resonates with Iceland’s recent funeral for Okjökull, the first glacier lost to climate change, memorialized in a site-specific plaque inscribed with “A letter to the future”: “Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”11 Such is only the latest instance where “we” becomes intolerable, hailing “our” complicity in the repression of historical responsibility for glacier-killing climate chaos—a repression, for instance, of the recognition of the hundred or so fossil-fuel companies largely responsible for climate breakdown, funding climate-change denial for decades, disabling governmental regulatory agencies, and refusing to stop the madness.12 While there’s real mourning to be done—for lost species, for historical and ongoing climate violence, for structural injustice—militancy is more than ever necessary, meaning a diversity of tactics dedicated to structural change, but grounded in careful political analysis and organizing.

Which is why it’s crucial that XR NYC has added an additional demand to the 2018 British platform, stressing climate justice principles. It clearly informed their mediagenic intervention at Rockefeller Center with a banner stating “Climate Change = Mass Murder,” positioned behind a golden statue of Prometheus, allegorical figure of the techno-utopian Anthropocene, at the symbolic headquarters of the US fossil industrial capital.13 It’s this radical political dimension that pins the injustice of uneven climate chaos to institutional culprits that needs amplification—rather than simply opposing the movement of XR, given its naive policy proposals, color-blindness, lack of structural analysis, and basic misunderstanding of the police as a function dedicated to protecting the powerful elite (which tear gas, again, helps to clarify).14 For, until XR and similar groups sharpen their analysis, “climate emergency” remains an unstable discourse, potentially only reaffirming the ruling order—an emergency without emergence, one blocking the rise of radical difference—where the “beyond political” framing opens a door to the financial co-optation of green capital, as much as invites the state of exception to take command.

***

If climate breakdown appears as the greatest threat to capital—to its logic of infinite growth on a finite planet—then we can only expect the powerful few to defend their outsized interests and claim on resources. Indeed, as 350.org, Climate Emergency Fund, and Climate Mobilization organize for “emergency,” at stake are trillions in decarbonization funds (distributed across diverse financial markets, institutional investment, and pension funds), on which the green nonprofit industrial complex has its eyes fixed, as we move from divestment to reinvestment in a renewable economy.15 Global climate emergency, in this vein, becomes financial insurance, redirecting toward market-friendly solutions what could otherwise be—what might still become—the greatest revolutionary force in history: a multispecies and anti-capitalist insurgency of unprecedented proportions.16 In this sense, the main liability of XR’s “beyond-political” emergency is catastrophe-become-financial-opportunity: fossil divestment brings green reinvestment, net-zero carbon necessitates sequestration and geoengineering technologies, and failing ecosystems stimulate monetizing natural capital and carbon offsetting. Such is clear, for instance, when Brazil’s foreign minister claims “opening the rainforest to economic development” is “the only way to protect it”—exemplifying the worn-out logic whereby economic growth masquerades as climate solution.17 The Bolsonaros, Dutertes, Netanyahus, and Trumps are happy to declare emergency, but only one of their own making, likely shrouded in tear gas.

According to this scenario, climate emergency (as a paradoxical demand to change everything so as to keep things the same) risks consigning us to an endless present of authoritarian capitalism. Anything to distract us from and bypass the real disaster as seen from the perspective of financial elites: a radical Green New Deal, meaning structural decarbonization dedicated to social justice, economic redistribution, smart degrowth, democratization, and decolonization, with the integral participation of historically oppressed and formerly excluded peoples.18 As the Fanon-inspired climate-justice coalition Wretched of the Earth writes in their open letter to XR, environmentalists’ often whitewashed positions tend to forget others’ long-term struggles, particularly those of black, brown, and indigenous communities, and the fact that climate emergency really dates to 1492.

For those of us committed to amplifying the insurrectionary potential of movements like XR (and doing the work of political organizing toward those ends), it is clear that we need to refocus on specific justice-oriented, eminently political demands—including implementing a just transition, holding corporations accountable, ending militarism, definancializing nature, replacing borders with radical hospitality, and guaranteeing universal health care, free education, healthy food, and adequate income for all (the demands of Wretched of the Earth).19 Without doing so, one’s climate emergency risks erasing others’ historical oppression, one’s future, another’s past, one’s privilege, another’s misfortune. “In order to envision a future in which we will all be liberated from the root causes of the climate crisis—capitalism, extractivism, racism, sexism, classism, ableism and other systems of oppression—the climate movement must reflect the complex realities of everyone’s lives in their narrative.”20 The challenge is to render these complexities proximate and mutually informing, centering them honestly and sensitively, by thinking emergencies together, and collaborating on solutions across difference. If not, then depoliticized emergency claims enable the Green New Deal to turn into a Green New Colonialism, founded on an extractive renewables economy enabling continued violent inequality, and a white futurism without end.21

***

Tear gas dramatizes these risks. As a cyanocarbon—related to cyanide, itself dependent on methane for its production—it chemically derives from hydrocarbons, the organic component of oil and gas. As such, it expresses the truth of climate breakdown as climate control. The weaponized environment—what Peter Sloterdijk terms “atmo-terrorism,” joining air to juridico-political and military frameworks22—functions as a medium of “humanitarian warfare,” rife with contradictions, historically and currently employed to defend power. One might believe tear gas to be more biopolitics than environmental concern. Like preemptive policing, surveillance, kettling, and counterinsurgency armaments, tear gas—as one more technology of crowd management—hypes safety, but enacts repression. As a substance that joins weaponized atmospheres to collective bodily control, tear gas creates biochemical environments that compel behavioral adaptation to regimes of power. As such, it’s more than biopolitical: it’s climatological, geontopolitical, intersectionalist, socioecological—where biogeophysical relationalities and ontological cuts splitting environments of life and death intersect with sociopolitical and techno-economic orders.23

Unlike typical greenhouse gases—say atmospheric carbon—that mostly remain unseen, tear gas is strategically visible and experientially affective: its calculus of impact materializes terrorizing fears of suffocation to catalyze physiological response. As a performative aesthetics of physiological persuasion, it redistributes the sensible according to chemical agents dividing bodies in space. Doing so, police choreograph multitudes, subjecting targets not only to the immediacy of pain, choking, and uncontrollable respiratory breakdown, but also, with chronic victims, to the slow violence of long-term illnesses—some of which is detailed in Triple Chaser, Forensic Architecture’s video about Safariland’s tear gas product presented at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, which was the scene of protests from its opening day. Insofar as Safariland forms part of a global regime of climate control that modulates atmospheres to the detriment of all but a tiny minority (part of a larger system of environmental injustice that sequesters clean air, water, and soil for the benefit of the few, relegating the impoverished to toxic sacrifice zones),24 the Kanders case elicits urgent concerns about the transformation of contemporary art in the era of climate emergency, especially when expanded to the realm of political ecology.

From the Forensic Architecture research project Triple Chaser, 2019. FA states on its website: “Using the Unreal engine, Forensic Architecture generated thousands of photorealistic ‘synthetic’ images, situating the Triple Chaser in approximations of real-world environments.” Photo: Forensic Architecture/Praxis Films.

A central part of FA’s project involved training a computer learning algorithm to visually recognize Triple Chaser grenades within large data caches, in order to both counter the manufacturer’s own nontransparency regarding its distribution markets, and aid campaigns against police and state violence worldwide. To do so, FA created a synthetic training data set to teach the classifier, resulting in a remarkable video sequence of machine learning visuality, containing seemingly infinite variations of colored background tessellations against which to test and improve the classifier’s abilities in identifying tear gas grenades, played under a disjunctive musical soundtrack. The commentary explains the selection, noting that in 2016 Kanders gave $2.5 million to the Aspen Music Festival, which renamed its Sunday concert series in his honor, inaugurating it with Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs. (More recently, Kanders’s sponsorship has supported a program of “music inspired by nature,” proposing another potential case study of institutionalized climate injustice.) As with Kanders’s Whitney, culture functions as a machine for laundering profiteering militarist brutality into virtuous philanthropy. But FA’s audiovisual juxtaposition offers a reverse tactic of de-artwashing, where culture is shockingly reunited with the oppressive technology serving as its condition of possibility. Over this complex montage, the narration describes Triple Chaser’s potential physiological effects—bronchial spasms, anaphylactic shock, pulmonary edema, convulsion, impaired breathing, and so on—based on Safariland’s safety guidance in an analytic deadpan (read by David Byrne) worthy of Harun Farocki.

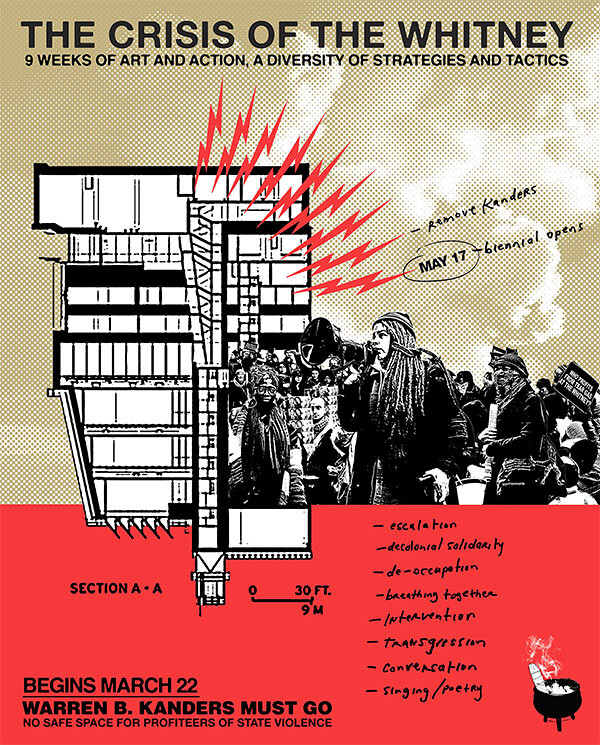

Poster for “9 Weeks of Art and Action,” 2019. Courtesy of Decolonize This Place.

Strauss wrote the 1948 composition during the last years of his life, in the apocalyptic wake of the Nazi Holocaust. In the video passage, the tear-worthy sonic pathos sourced in genocide paradoxically confronts the uncanny deathlessness of AI’s post-humanist immortality, glimpsed through sequential imaging that combines inhuman speed and seemingly endless repetition—in some ways reminiscent of the evolutionary paradigm shifts and disjunctive temporalities of Kubric’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, itself combining AI threats to humanity amidst futurist space exploration and transformative encounters with the alien sublime set to another Strauss score, the film concluding with a speculative remainder—post-human? inhuman? cyborg?—beyond all of what’s been. Triple Chaser is not so sanguine, including extensive consideration of the context of current-day Gaza, which provides further lessons in the necessity of expanding our conception of climate emergency beyond atmospheric carbon. Indeed, if tear gas materializes climate control atmospherics, then Gaza is its limit case, where structural debilitation figures as a mode of disaster capitalism, from which emerges a dystopian future captured by an endless now. When Triple Chaser details Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) snipers’ use of MatchKing bullets (made by Clarus, where Kanders serves as executive chairman), it connects to what Jasbir Puar critically analyzes as the “right to maim” (gassing or shooting to injure rather than kill). This latter figures as an emergent mode of biopolitics’ refusal to let die, a logic made clear in the statistics: during the December 2018 Great March of Return protests, on which FA focuses, the IDF killed 154 civilian protesters, including thirty-five children, but wounded more than six thousand people, evidencing the maiming directive as a grotesque ramification of “humanitarian” war.

Claiming the “right to maim” as a refusal to let die preconditions the “right to repair”—physiologically, infrastructurally, commercially—forming an endless cycle of destruction and production. It thereby reduces life to inhuman conditions, imprisoning a terrain between biopolitics and necropolitics, according to Puar, indicating an extreme modality of climate control where Gaza functions as laboratory for what’s to come more globally. Indeed, the Israeli occupation’s chronopolitics factors as a strategic aim of the state’s extended state of emergency (technically in operation since 1948), where the ongoing production of disaster is far from failure or accident, but an intended outcome, one that inevitablizes endlessness. Puar’s term for this is “prehensive futurity,” according to which the state makes “the present look exactly the way it needs to”—as catastrophic—“in order to guarantee a very specific and singular outcome in the future”—one dependent on Israeli interests—generating “the permanent debilitation of settler colonialism.”25 When taking into account the ecocidal use of white phosphorous and depleted uranium (the latter with a half-life of 4.5 billion years), both used in IDF operations, we confront a weaponized epigenetics of toxic inhuman futurity, a prehensive mode of climate control extending into incomprehensible time.26

Not surprisingly, Gaza’s anti-colonial protests are no Extinction Rebellion—and in fact no such formations exist in Palestine, only in Israel, where the group makes no mention of the occupation in its mission statement.27 Which reveals the selective and oppression-perpetuating privilege of XR’s “climate emergency” when the latter is so myopically conceived, when it refuses to connect to the long presence of colonial violence, including very real funerals and mass debilitation.

As an important corrective, Triple Chaser documents riot control targeting groups struggling for their very survival. It shows weaponized atmospherics destroying livability for multispecies life. And it unleashes data-crunching cyber-intelligence exceeding all human capability, a politically unstable technology for sure that FA repurposes for its own justice-oriented ends. Doing so, Triple Chaser reveals a triple extinction event that, according to my reading, remarkably expands contemporary climate emergency: first, ethnic destruction is enacted through neocolonial violence; second, environmental toxicity exacerbates mass species extinction and biological annihilation already in effect globally; and third, we glimpse the ultimate surpassing of humanity by AI—what Franco Berardi terms a “frozen immortality [that] emerges in the form of the global cognitive automaton” 28—as it comes to ominously “recognize” weapons of mass destruction. In each of these three endgames, the dying confront tear gas’s cruel irony of forcing a lacrymogenic self-mourning, a compelled crying in the act of experiencing one’s own annihilation. If, departing from FA’s own analysis, we preview in Triple Chaser the annihilation of biology by technology according to a speculative scenario wherein environmental catastrophe portends an AI future, then it’s because “silicon-based entities … do not need a breathable atmosphere, [and] life on Earth is just the raw matter from which a superior intelligence will emerge, with capitalism as its midwife,” as Ana Teixiera Pinto warns.29 As such, FA’s critical intervention, at least according to this speculative reading, dramatizes most broadly an ultimate threat that goes far beyond carbon-induced emergency claims: the post-biological death drive of petro-capitalist techno-utopianism—advanced by everything that tear gas represents.

From the Forensic Architecture research project Triple Chaser, 2019. FA states on it website: “Rendering images of our model against bold, generic patterns, known as ‘decontextualised images,’ improves the classifier’s ability to identify the grenade.” Image: Forensic Architecture/Praxis Films, 2019.

FA’s video concludes by stating: “We shared our findings with the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, who served Sierra Bullets with legal notice, warning that the exports of their bullets to Israel may be aiding and abetting war crimes.” As much as one might support such justice—as a non-reformist reform—it’s striking how such an expansive conceptual analysis of climate control couched in the conditions of settler-colonial violence and warning of an unfolding global triple extinction event ultimately leads to merely a liberal grievance claim, a claim hailing conventional juridico-political reason that has led to humanitarian war in the first place (about which FA is well aware30). Moreover, by focusing on corporate malpractice abetting allegedly criminal regimes, the grievance neglects to oppose tear gas in any context whatsoever. Of course FA’s larger practice comprises a growing list of dozens of case studies that collectively add up to meaningful opposition to structural forms of state and corporate violence, including numerous instances where socio-environmental and biopolitical violence converge in a multiplication of emergency conditions. Yet rather than allowing liberal grievance to neutralize radical social-movement opposition that surpasses the Kanders case, how might the latter offer a platform for considering the more ambitious political horizon of the structural transformation of governance itself? It is here that an additional rupture might emerge from climate emergency, propelled by social-movement energies.

***

Although not typically considered within the framework of climate politics, Decolonize This Place’s “9 Weeks of Art and Action” (March–May 2019) represented a concerted effort to remove Kanders from the Whitney. It comprised one vector in the group’s larger, ongoing project of the decolonization of life initiated through the “liberation of institutions”—“more than a critique of institutions, institutional liberation affirms the productive and creative dimensions of collective struggle.”31 The radical dimension of its collectivity—including such groups as Veterans Against the War, Brooklyn Anti-Gentrification Network, Comité Boricua En La Diáspora, Mi Casa No Es Su Casa, NYC Solidarity with Palestine, Queer Youth Power, P.A.I.N. Sackler, and many more32—drew on and affirms the power of solidarity as the necessary basis for alliance-building, practicing what Angela Davis calls “the indivisibility of justice” (rejecting not only art-world individualism and neoliberal social atomization, but the sway of identity politics into essentialist separatism33). Such collective struggle is forged in the materiality of oppression, which tear gas, in its negative cast, enacts by chemically joining multiple bodies and geographies of violence, rendering diverse grievances interconnected. Indeed, in her extensive study of tear gas, Ann Feigenbaum highlights how the chemical weapon historically targets environmentalists, people of color, the poor, LGBTQ activists, refugees and immigrants, the disabled and mentally unwell, young people and dissidents, forging the bonds of solidarity in oppressive climate control.34 In this regard, we can make sense of DTP’s slogan announced in a self-authorized banner drop over the Whitney’s façade: “When we breathe, we breathe together”—what we might call an intersectionalist climate justice put to task against the environmental injustice of violent policing, weaponized toxicity, and structural debility alike.

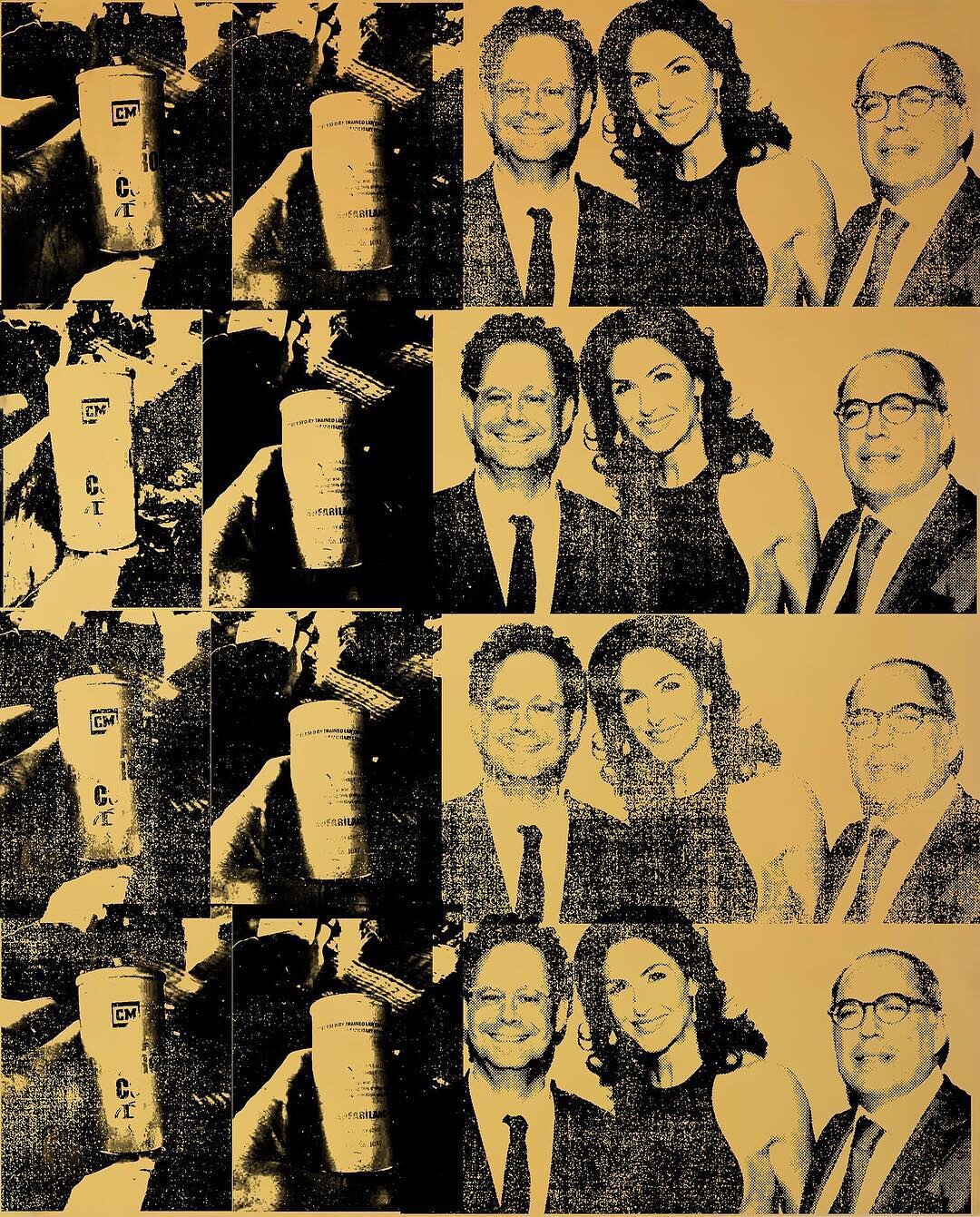

Following its organizing of an open letter signed by four hundred writers, scholars, and artists in May 2018, itself catalyzed by the movement against Kanders initiated by the Whitney’s own staff, DTP unfurled an all-out campaign of tactical media, agitprop design, Instagram feeds, and interventionist collective actions in the museum’s spaces. These occurred in coordination with the radical pacifist organization War Resisters League, already engaged in long-term struggle against Safariland, with the action resulting eventually in eight artists (including Forensic Architecture) withdrawing their work from the biennial.35 DTP’s militant media also riffed off the art of the Whitney’s temporary exhibitions (partly funded by Kanders), including its ongoing Warhol retrospective, mirroring the Pop artist’s appropriation aesthetics, specifically the latter’s Death in America series, while redirecting the mournful iconography toward their social and environmental justice aims.36 Moving from Pop art to agitprop, the serial images of museum spectacle—showing Kanders, his wife, and fellow trustee Allison Kanders standing with Whitney Museum director Adam Weinberg—explode in representational proximity to tear gas canisters used in oppressive police actions. Revealing the disastrous intertwinement of contemporary power and culture in the era of carceral capitalism, military neoliberalism, and apocalyptic populism, DTP organizes the collective energy to overcome it.37

Not that the approaches of FA’s humanitarian grievance and DTP’s decolonial institutional liberation are mutually exclusive; indeed they are allied. No doubt we need both, and all others that can aid in the process of emancipation from the climate control system governed by war profiteer philanthropists, “beyond political” institutions, and oppressive states claiming the right to maim. These latter propose a matrix of causality driving global climate chaos, which seeks to turn climate emergency into financialized opportunity for the further accumulation of wealth and power, leaving the world destitute and dead in its wake. To escape these conditions, we must move from emergency to emergence—of radical difference, of the residual and the not-yet—making a just transition into the future, where the not-yet may be glimpsed in the already-here, grounded in the traditions of the oppressed, and generating new emancipatory possibilities on that basis.

Following the coordinated, sustained actions of groups like DTP, Kanders did resign in July 2019, constituting a major success. But, as we’ve seen, DTP’s motivations exceed this goal, forming part of the “ongoing project of decolonization” as “a mode of ‘epistemic disobedience,’ an immanent practice of testing, questioning, and learning, grounded in the work of movement-building,” opposed to “the entire settler-institutional nexus of art, capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy.”38 As such, their example, if operating at a smaller scale, provides an urgent way to massively expand and radicalize XR’s climate emergency, where climate justice is inextricable from economic justice, housing justice, migrant justice, democratic justice, and decolonial justice. The goal being not simply to reform neoliberal museum boards, but to catalyze the structural transformation of our political economy as the only way to address the manifold socio-ecological and climate emergencies of our times. It is not at all surprising that DTP’s analysis, in the case of Safariland and the Whitney, begins with tear gas, which, as we’ve seen, immediately repositions ecology and climate as terms inextricably entangled in the politico-economic framework of late-capitalist climate control. It’s not that tear gas displaces fossil-fuel causality in this analysis of climate emergency; rather it reveals the latter’s truth as thoroughly enmeshed in petro-capitalist governmentality and its attendant forms of violence.

Conversely, depoliticized emergency claims invite instrumentalization toward purposes other than democratic equality and social justice. This is similarly the case with proposals for a Green New Deal, which may very well represent our best global hope at mitigating climate catastrophe; but it too is inadequate if separated from decolonization—for instance, as part of a Red Deal expressive of indigenous climate justice.39 Just how the Green New Deal transition is implemented—whether ground-up, smartly de-growth-directed, and centering agro-ecological smallholders, working-class labor, indigenous land-protectors, and frontline communities, or as a technocratic, fortress-based, elitist, ethno-nationalist economy—will necessarily be a site of collective struggle. But one thing’s for sure: narrowly defined climate emergency propels movement in the opposite direction, investing post-political governance with emergency powers poised to decarbonize in its own interests, or, worse, to resemble something closer to eco-fascism than internationalist eco-socialism.

“In order to envision a future in which we will all be liberated from the root causes of the climate crisis—capitalism, extractivism, racism, sexism, classism, ableism and other systems of oppression—the climate movement must reflect the complex realities of everyone’s lives in their narrative,” writes Wretched of the Earth in their open letter to XR.40 Building what might be called a prehensive futurity of justice will, of course, take collective commitment and time, exceeding the event-obsessed convergences of culture-industry social practice, and equally spectacular activist protests, ultimately requiring something like the multiple-generations expansiveness of indigenous time-relations, of creating worlds by living and struggling together, across difference, over the long term. This means a commitment to “long environmentalism,” the labor of building solidarity and mutual-aid networks over months, years, generations, as probably the only place where a radical politics of emergency can truly emerge—rooted in the broadly shared concern of collective survival—even if that means rethinking the temporal immediacy of emergency itself in times of unprecedented uncertainty.41 It entails committing to building relations of responsibility and accountability that can lend trust in justice, in thinking climate emergencies relationally, beginning with the history of Anthropocene violence stretching back hundreds of years and continuing with current and near-future threats of ongoing climate chaos. As such, those of us bound in solidarity and committed to creating a collective future beyond climate breakdown—where tear gas reveals its expansive entanglements—must certainly decolonize this place, and this and that one too, organizing a transnational network of resistance capable of challenging the transnational power of capital.42 But we must also decolonize our future, rescuing it from the disaster of green capitalist, and worse eco-fascist, “inevitability” facilitated by an irresponsible emergency politics.

Emily S. Rueb, “‘Freedom Gas,’ the Next American Export,” New York Times, May 29, 2019 →.

See →.

Wen Stephenson, “Against Climate Barbarism: A Conversation with Naomi Klein,” Los Angeles Review of Books, September 30, 2019 →; and Naomi Klein, On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal (Simon & Schuster, 2019).

See Jonathan Watts, “We have 12 years to limit climate change catastrophe, warns UN,” The Guardian, October 8, 2018 →.

See the evidence for these statistics as backed up by leading scientists in the following: William E. Rees, “Yes, the Climate Crisis May Wipe out Six Billion People,” The Tyee, September 18, 2019 →; Robert Hunziker, “Earth 4C Hotter,” Counterpunch, August 23, 2019 →; Gaia Vince, “The heat is on over the climate crisis. Only radical measures will work,” The Guardian, May 18, 2019 →. Recent scientific research estimates conservatively that more than 250,000 deaths occur annually already owing to climate change, including exacerbated conditions of malaria, diarrhea, heat stress, and malnutrition, as reported here: Jen Christensen, “250,000 deaths a year from climate change is a ‘conservative estimate,’ research says,” CNN, January 16, 2019 →.

Bill McKibben, “A World at War,” The New Republic, August 15, 2016 →.

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October, vol. 51 (Winter 1989): 3–18.

See →.

Kyle P. Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises,” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 1, no. 1–2 (2018).

See Agence France-Presse, “Iceland holds funeral for first glacier lost to climate change,” The Guardian, August 18, 2019 →.

See Tess Riley, “Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions, study says,” The Guardian, February 14, 2018 →; and the cartographic project of Influence Map, which details who owns the world’s major fossil fuel companies and which financial and media firms are defending their interests →.

XR USA’s Fourth Demand reads: “We demand a just transition that prioritizes the most vulnerable people and indigenous sovereignty; establishes reparations and remediation led by and for Black people, Indigenous people, people of color and poor communities for years of environmental injustice, establishes legal rights for ecosystems to thrive and regenerate in perpetuity, and repairs the effects of ongoing ecocide to prevent extinction of human and all species, in order to maintain a livable, just planet for all.” See →.

See Cory Morningstar, “The Manufacturing of Greta Thunberg—for Consent: The Political Economy of the Non-Profit Industrial Complex,” 2019 → (though Morningstar mistakenly collapses the radical message of Thunberg into the neoliberal discourse of NGOs surrounding her). Also see the critique of environmentalist NGOs in Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate (Allen Lane, 2014).

Massimiliano Tomba, Insurgent Universality. An Alternative Legacy of Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2019). Tomba explains that “insurgent universality” extends beyond the contemporary limits of single-issue identity politics, and “refers to the excess of equality and freedom over the juridical frame of universal human rights,” whereby the rebellious disrupt and reject an existing political and economic order. Here I’m suggesting that XR might yet hold the potential to extend further that radical political claim toward a more-than-human assembly.

As reported by the BBC, “US and Brazil agree to Amazon development,” September 14, 2019 →.

See Thea Riofrancos, “Plan, Mood, Battlefield – Reflections on the Green New Deal,” Viewpoint, May 16, 2019 →.

In this regard, my own positioning is not only as an academic, but also as a member of DSA (Democratic Socialists of America) and its Ecosocialist Working Group in Santa Cruz. See →.

Wretched of the Earth, “An Open Letter to Extinction Rebellion,” Common Dreams, May 4, 2019 →. Some articulations of XR are smarter than the UK-based officially stated agenda. See for instance the article about XR as more than a climate protest, connecting to hundreds of years of European colonialism, by XR member Stuart Basden, “Extinction Rebellion isn’t about the Climate,” Medium, January 10, 2019 →.

On such dangers, see Nicholas Beuret, “A Green New Deal Between Whom and For What?,” Viewpoint, October 24, 2019 →.

See Peter Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air (Semiotext(e), 2009).

On this convergence, see Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Duke University Press, 2016); Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, “Michael Brown,” boundary 2 42, no. 4 (November 2015); and Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016). Also see T. J. Demos, “Ecology-as-Intrasectionality,” Panorama (Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art), Spring 2019 →.

“In both its physical design and its application throughout history, tear gas is for the control of economically, politically, and socially vulnerable populations, enforced by mentalities and behaviors of constantly reworked white supremacy … Riot control is, and has always been, the business of protecting the wealth of a tiny minority.” See Anna Feigenbaum, Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of World War I to the Streets of Today (Verso, 2017).

Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Duke University Press, 2017), 149.

The mission statement of Extinction Rebellion Israel includes the following: “We and our children have to deal with unimaginable terror as a result of floods, fires, extreme weather, loss of crops and the inevitable collapse of society as a whole. We didn’t prepare ourselves to deal with the dangers already here. The time for denial has passed. We know the truth about climate change. Time to act” →.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “Game Over,” e-flux journal, no. 100 (May 2019) →.

Ana Teixeira Pinto, “Artwashing—On NRx and the Alt Right,” Texte zur Kunst, July 4, 2017.

See Eyal Weizman, The Least of All Possible Evils: A Short History of Humanitarian Violence (Verso, 2017).

For more on this, including sensitive discussion of how decolonization first and foremost entails the return of land and sovereignty to indigenous peoples, but, and to that end, also entails the emancipation of imagination, aesthetics, and culture from capital, see MTL Collective, “From Institutional Critique to Institutional Liberation? A Decolonial Perspective on the Crises of Contemporary Art,” October 165 (Summer 2018), 206.

For its list of collaborators, see Decolonize This Place, “The Crisis of the Whitney,” May 19, 2019 →.

Angela Davis, Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine and the Foundations of a Movement (Haymarket Books, 2015); and DTP: “Among the lessons of the Kanders crisis has been the limitations of liberal versions of ‘identity politics.’ Why would we imagine that anyone’s racial or ethnic background necessarily aligns that person with justice, or assume any unity between those who share a skin color? As the saying goes, ‘All my skin folk ain’t kinfolk’ … Our work in mobilizing against Kanders and beyond has focused not on demographic diversity but on solidarity between struggles. Solidarity is not a box to be checked—it is difficult and painstaking work that requires us to ask: what debts do we owe to each other? What are we willing to sacrifice? How do we become political accomplices?” Decolonize This Place, “After Kanders, Decolonization Is the Way Forward,” Hyperallergic, July 30, 2019 →.

Feigenbaum, Tear Gas, 1–14.

See Hrag Vartanian, Zachary Small, and Jasmine Weber, “Whitney Museum Staffers Demand Answers After Vice Chair’s Relationship to Tear Gas Manufacturer Is Revealed,” Hyperallergic, November 30, 2018 →.

Among my references are: Wendy Brown, “Apocalyptic Populism,” Eurozine, August 30, 2017 →; Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism (Semiotext(e), 2018); and Retort, Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War (Verso, 2005).

MTL Collective, “From Institutional Critique to Institutional Liberation?,” 194; and DTP, “The Crisis of the Whitney is Just the Beginning,” February 25, 2019 →.

Wretched of the Earth, “Open Letter to Extinction Rebellion.”

See Subhankar Banerjee, “Long Environmentalism: After the Listening Session,” in Ecocriticism and Indigenous Studies: Conversations from Earth to Cosmos, eds. Salma Monani and Joni Adamson (Routledge, 2017), 62–81.

For one such vision, see Bhaskar Sunkara, The Socialist Manifesto: The Case for Radical Politics in an Era of Extreme Inequality (Verso, 2019).