1.

Since 2000, there has emerged a new wave of interest in the factographic movement within the Soviet avant-garde. It is still too early to give the movement, which is associated with Sergei Tretyakov, a definitive historical and aesthetic assessment. The documentary impulse in Soviet culture embodied in factography is still mainly regarded as a mediator between the historical avant-garde and the realist paradigms that played starring roles in the evolution of Stalinist culture and socialist realism.1 However, a number of scholars have recently claimed that the factographic program was not a “move backwards, following the experimental semioclasm of the early avant-garde” or a “link leading to the apparently more conservative practices of socialist realism,” but rather a “radicalization of an earlier avant-garde slogan: art into life.”2

The duality of views on factography has to do with the transitional nature of the period during which it emerged and flowered. The years between 1927 and 1932, conventionally referred to as the Soviet cultural revolution, coincide not only with the so-called Great Break (velikii perelom) and the first Five-Year Plan, but also with other important changes—for example, the transformation of the experimental avant-garde into a socialist-realist project, and the transformation of the revolutionary, montage-driven cinema of the 1920s into the talking pictures “for the millions” of the 1930s. It is quite difficult, of course, to give an unambiguous historical assessment of the time of the great shift. At the same time, this ambivalence partly fuels special interest in the period.3

In this article, I will examine the problem of returning to the past on the basis of two examples—one of them old and quite well known, the other relatively new to literary studies. In both cases, I would like to analyze how the work of Sergei Tretyakov was made relevant again and think about what this return means. Both of my examples involve Germany, so you could say we are dealing with a return to Tretyakov’s work with a German “accent.”

2.

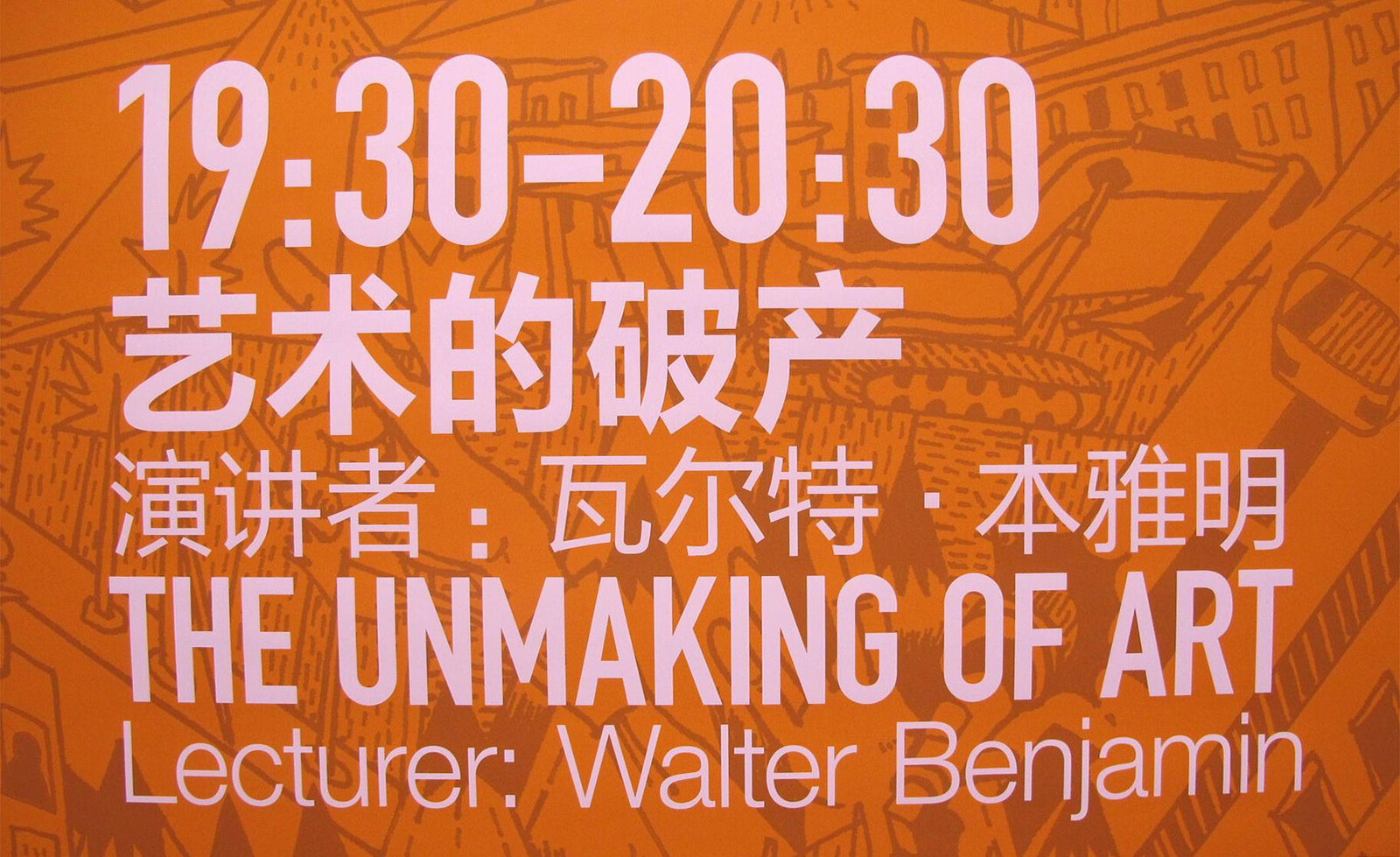

In his famous lecture “The Author as Producer,” Walter Benjamin argues that there is a certain relationship between tendency and technique:

If, therefore, we stated earlier that the correct political tendency of a work includes its literary quality, because it includes its literary tendency, we can now formulate this more precisely by saying that this literary tendency can consist either in progress or in regression of literary technique. You will certainly approve if I now pass, with only an appearance of arbitrariness, to very concrete literary conditions. Russian conditions. I would like to direct your attention to Sergei [Tretyakov], and to the type (which he defines and embodies) of the “operating” writer.4

Although Benjamin adds, “Of course it is only one example: I am keeping others in reserve,” there can be no doubt that the overall impression made by this passage on Tretyakov far surpasses a simple example.5 Indeed, Benjamin devotes nearly the entire first half of his lecture to a man with whom his audience would have been unfamiliar. According to Benjamin, “This operative writer presents the clearest example of the functional relation which always exists, in any circumstances, between correct political tendency and a progressive literary technique.”6

So why does Benjamin cite the then-obscure Tretyakov in his lecture? Its entertaining backstory has already been studied in considerable detail by Katerina Clark and Maria Gough.7 Bertolt Brecht’s closest Russian friend, Tretyakov, spent nearly six months in Germany, from October 1930 to April 1931, during which time he lectured in several German cities. In Berlin in January 1931, Tretyakov spoke in detail about a special model of cultural behavior he called the type of the “operative” writer, based on his stays at a collective farm over a two-year period from 1928 to 1930. Benjamin relays:

When, in 1928, at the time of the total collectivization of agriculture, the slogan “Writers to the kolkhoz!” was proclaimed, [Tretyakov] went to the “Communist Lighthouse” commune and there, during two lengthy stays, set about the following tasks: calling mass meetings; collecting funds to pay for tractors; persuading independent peasants to enter the kolkhoz [collective farm]; inspecting the reading rooms; creating wall newspapers and editing the kolkhoz newspaper; reporting for Moscow newspapers; introducing radio and mobile movie houses; and so on. It is not surprising that the book Commanders of the Field, which [Tretyakov] wrote following these stays, is said to have had considerable influence on the further development of collective agriculture.8

We do not know whether Benjamin heard Tretyakov’s lecture. However, given the huge interest in the lecture amongst Berlin’s intellectuals (Siegfried Kracauer, among others, wrote a review of it), we can assume Benjamin was well acquainted with its contents.

Even more interesting, however, is the fact that three years after Tretyakov’s lectures, Benjamin, who was in exile in Paris, mentions his model in his writing. Why Tretyakov, and why at that particular time in that particular place? While it is true that concepts such as production and technique were vital components in Tretyakov’s model, this also applied to first-generation productivism and constructivism. What, then, does factography have to do with it?

To answer this question, we should recall the historical context of factography’s emergence. Dominated by productivism and constructivism, the state of the Soviet art world at the time can perhaps be most vividly captured by the slogan “From composition to construction.” Here the word “composition” refers to current art theory and decorative conventions, but above all it has to do with the so-called linguistic (symbolic) method in a broader sense. On the other hand, the word “construction,” which has technical nuances, is focused on material itself. Terms such as “texture” and “tectonics,” which were vigorously discussed at the time, clearly show a state of affairs in which material was the benchmark. The essence of the transition from composition to construction, however, was that sensual materiality transcends signification, that is, the starting point for all artistic work is matter, not signs.9

Because production was understood as the construction of materials, there was no room in it for words and texts. As we know, the first generation of productivists claimed that, in the name of production, utilitarian (“practicable”) things to be used in daily life could be designed—from new factory uniforms to folding stools, optimized for communal flats.10 This, however, did not apply to literature, because it dealt with intangibles, with concepts and values. In this context, what did the emergence of factography, or more precisely, the “literature of fact,” signify?

The emergence of factography meant the return of language in a broad sense to art, that is, the deliberate reorientation of art-making towards information and discourse. Benjamin Buchloh, in his groundbreaking article “From Faktura to Factography” (1984), clearly identified the Soviet avant-garde’s paradigmatic shift from immersion in physical production (faktura) to an emphasis on the informational and communicative factors in art-making (factography).11 This description of factography enables us to better understand the thread that connected Benjamin in Paris in 1934 to Tretyakov in Moscow in the late 1920s.

What did Benjamin and Tretyakov have in common? The so-called Existenzrecht, that is, the right of artists and intellectuals to exist. In the late 1920s, Tretyakov confronted the question of how artists can justify their existence, just as Benjamin faced the same question in the Weimar Republic’s final years. Whereas Tretyakov had approached the issue by asking whether there was a place for literature and language in art during the reign of productivism, Benjamin wondered whether intellectuals and artists could maintain their former social status and roles when faced with the impending threat of fascism.

Benjamin’s interest in the Soviet Union, a country where a revolution really had taken place, and more specifically his interest in the new type of intellectuals and writers generated in that other world, arose from his grappling with a similar set of questions.12 Benjamin wrote that

nothing will be further from the author who has reflected deeply on the conditions of present-day production than to expect, or desire, such works. His work will never be merely work on products but always, at the same time, work on the means of production. In other words, his products must have, over and above their character as works, an organizing function.13

When Benjamin used the word “organizing,” did he have in mind such “fathers” of the term as Alexei Gastev, Alexander Bogdanov, and Platon Kerzhentsev? We cannot answer this question. Nevertheless, we can confidently say one thing: when Benjamin listed all the not-very-writerly tasks that had fallen on Tretyakov’s shoulders on the collective farm (e.g., producing wall newspapers and collecting money for tractors), along with the need to fight and intervene in circumstances, he had something else in mind—namely, not only a strategy for effectively working with the people but also for successfully surviving in a collective, that is, a technique for living among the masses.14

During his two years at the collective farm, Tretyakov really did undergo the “change of functions” (Umfunktionierung) of which Benjamin, following Brecht, spoke. We should not forget, however, that while Tretyakov moved away from the functions of a professional in the narrow sense of the word and thus found himself in completely heterogeneous areas, he became a talented organizer who was able to put them all together. In other words, in becoming part of the farm, he proved his right to exist among the people.

Tretyakov’s story can thus be considered an exemplary answer to the question of how contemporary artists can justify their existence. The question was first systematically posed by Tretyakov, and later effectively reconfigured by Benjamin. During the latter half of the twentieth century, the question was modified, becoming a universal problem that returned again and again, proving its relevance under capitalism, fascism, and communism.

Given the global trend of a precipitous rise in the number of intellectual workers employed in immaterial labor, resulting in the ever more apparent precaritization of artists and intellectuals, Tretyakov should be regarded as one of the pioneers in raising this general problem. With this in mind, let us turn to the second example of a return to Tretyakov’s legacy.

3.

Tretyakov turns up again in the works of contemporary artist, filmmaker, and theorist Hito Steyerl.

Liberally combining documentary and experimental styles, Steyerl’s videos and films have provoked heated discussions among critics, curators, and scholars concerned with the politics of images and technology. Instead of treating images as pure quantities, Steyerl has interpreted them in the light of capitalism, changing political circumstances, and their own nature as physical and digital objects. In particular, her works are known for their close, original reading of the economy, production, and consumption of images under capitalism in the twenty-first century.

Steyerl’s In Free Fall, a thirty-two-minute film released as a single-channel HD video in 2010, is a peculiar take on Tretyakov’s innovative ideas.15 The film reconstructs the life story of a Boeing 707 jet. It opens with an image of the Mojave Air and Space Port in the California desert, a junkyard-cum-cemetery where planes are brought to die. The story of the deceased thing thus begins with its grave.

The story of the Boeing is truly dramatic. After serving in the fleet of TWA, the passenger airline founded by the American business tycoon, pilot, engineer, and film mogul Howard Hughes, who directed the 1930 film Hell’s Angels and produced such films as the 1932 Scarface, the plane was sold to the Israeli air force. They then used it in the famous 1976 raid on Entebbe, the mission mounted to rescue hostages on another passenger airliner, which had been hijacked by Palestinian and German militants from the PLO and commandeered to Uganda.

After the raid on Entebbe, the plane was used as a prop and blown up for the 1994 Hollywood blockbuster Speed. This was not the vessel’s end, however. After being blown up on the set of Speed, the leftover aluminum parts were sold to a Chinese DVD manufacturer, and so the airliner eventually became a laser disc. The plane thus lost its former materiality, becoming another thing, a disc for storing, among other things, footage of the explosion that destroyed it.

As we can see, the film is a literal realization of Tretyakov’s ideas. In the second of its three parts, Steyerl mentions Tretyakov’s “The Biography of the Object” in a voice-over in German that is subtitled in English: “In 1929 Soviet writer Sergej Tretiakov drafts a ‘biography of the object.’ An object tells us about its producers and users. Its biography represents a profile of social relations. The biography of the object includes its destruction.”16

As Steyerl reads these lines, we see ticks gnawing at the plane’s fuselage and innards, reminding us that we are dealing with physical objects, not made-up metaphors. Next to the wreckage lies a portable DVD player on whose screen we see a subtitle: “The Biography of the Object: 4X-JYI.” (4X-JYI is the number of the Boeing 707 blown up in Speed.)

Tretyakov’s ideas emerged as part of the so-called war with the novel. Novels are always psychological machines in which subjectivity and affect prevail at the expense of objects and objectivity. As Tretyakov writes, “In the novel, the leading hero devours and subjectivizes all reality.” However, the biography of the object is a powerful alternative method. “Thus: not the individual person moving through a system of objects, but the object proceeding through the system of people—for literature this is the methodological device that seems to us more progressive than those of classical belles lettres.”17

There is, however, something more important here than genre and plot, and that is the question of what is enabled by the new object-focused approach. The essence of the approach is that, by telling a thing’s story, we come to see the social relations behind its production and consumption. The biography of the object is a new type of narrative in which the story of a thing becomes the story of the people who made it, providing a cross section of the social relations that shaped them. According to Tretyakov:

The biography of the object is an expedient method for narrative construction that fights against the idealism of the novel … The biography of the object has an extraordinary capacity to incorporate human material. People approach the object at a cross section of the conveyer belt. Every segment introduces a new group of people. Quantitatively, it can track the development of a large number of people without disrupting the narrative’s proportions. They come into contact with the object through their social aspects and production skills. The moment of consumption occupies only the final part of the entire conveyer belt. People’s individual and distinctive characteristics are no longer relevant here. The tics and epilepsies of the individual go unperceived. Instead, social neuroses and the professional diseases of a given group are foregrounded.18

Obviously, the structure of Steyerl’s film, which tells us the complicated story of an airplane, is more focused on a fundamental or, if you will, substructural dimension than on superficial biography. The airplane’s biography itself demonstrates the social neuroses and professional diseases of twentieth-century capitalism, replete with disasters, economic depression, terror, and globalization.

4.

What is really remarkable, however, is that the connection between Steyerl and Tretyakov is not limited to the essay “The Biography of the Object.” In this regard, we should examine Steyerl’s essay “In Defense of the Poor Image,” which brought her international fame and has been regarded as a kind of manifesto on her part.19

The “poor image” of the title refers to visual files—say, in the GIF or AVI formats—that have been obtained after being damaged during their production and previous use. In other words, they are low-quality, low-resolution images.

As copies of original images and films that circulate on the internet, especially on social media, chat sites, and pirate websites, such poor images are easily subjected to various types of reprocessing. Naturally, the “aura” of original, high-quality images and the “unique, disposable being” of watching a movie in a theater vanish during these transformations. Steyerl defines the poor image as follows:

The poor image is a rag or a rip; an AVI or a JPEG, a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances, ranked and valued according to its resolution … The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled … Poor images are the contemporary Wretched of the Screen, the debris of audiovisual production, the trash that washes up on the digital economies’ shores.20

Indeed, Steyerl evinces this attitude not only theoretically but also practically. In Free Fall is chockablock with cheap derivative images, images that were used in other films, music videos, advertisements, and so on. In some sense, the entire film might seem like a product of recycling, like the remains of the Boeing, which were turned into DVDs.

By referring to such images as lumpen proletarians, trash washed up on the shore of digital economies, and so on, Steyerl not only vigorously defends them but tries to discover in them new cultural meanings and political potential:

But, simultaneously, a paradoxical reversal happens … In the age of file-sharing, even marginalized content circulates again and reconnects dispersed worldwide audiences. The poor image thus constructs anonymous global networks just as it creates a shared history. It builds alliances as it travels, provokes translation or mistranslation, and creates new publics and debates. By losing its visual substance it recovers some of its political punch and creates a new aura around it. This aura is no longer based on the permanence of the “original,” but on the transience of the copy.21

As we can surmise, Steyerl’s position here echoes that of Benjamin, or rather, the theoretical stance outlined in his famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which she has updated in keeping with the digital image’s ontology. As Steyerl writes, “The poor image has been uploaded, downloaded, shared, reformatted, and reedited. It transforms quality into accessibility, exhibition value into cult value, films into clips, contemplation into distraction.”22

It is worth recalling that Benjamin wrote “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which went on to become a primary manifesto of twentieth-century art, exactly a year after he wrote “The Author as Producer.”

A kind of chain has thus emerged, stretching from Tretyakov to Benjamin to Steyerl. Perhaps we could say that Steyerl, by combining Tretyakov and Benjamin’s ideas in her own way, has restored not so much Tretyakov himself as the Tretyakov who made such a decisive impact on Benjamin’s famous lecture.

Theodor Adorno once noted that when Benjamin wrote “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” he had wanted to outdo Brecht. If this is true, then perhaps the person who helped him outdo Brecht was Brecht’s Russian friend Sergei Tretyakov—although this claim would require a separate, detailed study.

See, for example, Maria Zalambani, Literatura fakta: Ot avangarda k sotrealizmu (Literature of the fact: From the avant-garde to socialist realism) (Akademicheskii proekt, 2006); and Elizabeth Papazian, Manufacturing Truth: The Documentary Moment in Early Soviet Culture (Northern Illinois University Press, 2009).

Devin Fore, “Sergei Tret’iakov: ‘Fakt’” (Sergei Tretyakov: The fact), in Formal’nyi metod: Antologiia russkogo modernizma (The formal method: An anthology of Russian modernism), vol. 2, ed. Serguei Oushakine (Kabinetnyi uchenyi, 2016), 184–85.

It would be wrong to say, of course, that claims for the significance and relevance of a particular period have only to do with its ambivalence. If a period is recalled over and over again—in other words, if the ideas and issues typical of the period alone resurface in a similar historical context—we can speak of the period’s exceptional importance. It is assumed that by reinterpreting the period, which has often been omitted in accounts of the so-called historical avant-garde, we can not only move away from the facile contrast between the 1920s and 1930s but also reevaluate the Soviet art of the cultural revolution in the light of its unexpected modernness. For example, according to the art scholar Ekaterina Degot, “A view not clouded by knee-jerk anti-communism discovers in the art of the cultural revolution a huge similarity with the art practices of the early twenty-first century … Far from representing a return to nineteenth-century realism, Soviet realist art foreshadows the conceptual practices of the late twentieth century.” See E. Degot, “Sovetskoe iskusstvo mezhdu avangardom i sotsrealizmom, 1927–1932” (Soviet art between the avant-garde and socialist realism, 1927–1932), Nashe nasledie, 2010, 93–94 →. This, however, is a separate topic that is beyond the scope of this article.

Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer (Address at the Institute for the Study of Fascism, Paris, April 27, 1934),” trans. Edwin Jephcott, in Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 1931–34 (Belknap Press, 1999), 770.

Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” 771.

Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” 770–71.

Katerina Clark, Moscow, the Fourth Rome: Stalinism, Cosmopolitanism, and the Evolution of Soviet Culture, 1931–1941 (Harvard University Press, 2011), 42–77; Maria Gough, “Paris, Capital of the Soviet Avant-Garde,” October, no. 101 (Summer 2002): 53–83.

Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” 770.

“Constructivists abandoned the enervated field of language and signification—which was dismissed as the dominion of illusionism, thought, verisimilitude, and mere secondary effects—in order to commune with systems of physical force. Matter itself, not the sign thereof, was the point of departure for the anthology of INKhUK (Institute of Artistic Culture) writings, From Representation to Construction, which was proposed by Brik in September 1921 to be the group’s collective opus on the transition from composition to construction.” Devin Fore, “The Operative Word in Soviet Factography,” October, no. 118 (Fall 2006): 99.

Tselesoobraznost’ was a keyword in the famous debates that took place at the INKhUK from 1920 to 1922. Usually translated into English as “expediency,” the word can be translated literally as “formed in relation to a goal.” Not all the artists of the INKhUK were equally enamored of the productivists’ utilitarian imperative. There were some groups who were determined to defend artists from what they regarded as productivism’s narrow utilitarianism, proclaiming the right of artists themselves to make decisions about the purpose and practicability of things. For a more detailed discussion, see Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (MIT Press, 2005).

Benjamin Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October, no. 30 (Autumn 1984): 82–119.

This interest was one of the main things that prompted Benjamin to go to Moscow. He went there in hopes of finding the characteristics of the professional intellectual. However, his hopes were doomed to be crushed, as was his unhappy love affair. See W. Benjamin, Moscow Diary, trans. Richard Sieburth (Harvard University Press, 1986).

Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” 777.

Gerald Raunig recalls the Proletkult’s previous experiments in organizing collectives, experiments in which Tretyakov was involved: “Tretyakov had also worked together with Eisenstein and Arvatov on the ‘Experimental Laboratory of Kinetic Constructions’ of the Moscow Proletkult. All possible forms of social assembly were to be experimentally tested in the workshops in the course of training: ‘Conference, banquet, tribunal, assembly, meeting, audience space, sport events and competitions, club evenings, foyers, public cantines, mass celebrations, processions, carnival, funerals, parades, demonstrations, flying assemblies, company work, election campaigns, etc. etc.’ It almost seems as though Tretyakov seized a long sought opportunity almost a decade later with his work in the kolkhoz to try out the same work on the forms of organization that he had conducted in the meanwhile closed laboratory of the Proletkult, but now decidedly outside the realm of art institutions.” G. Raunig, “Changing the Production Apparatus: Anti-Universalist Concepts of Intelligentsia in the Early Soviet Union,” trans. Aileen Derieg, Transversal, September 2010 →.

I owe thanks to Jihoon Kim, one of the leading film and media researchers in Korea, and the supervisor of the Korean translation of Steyerl’s book, The Wretched of the Screen, for the introduction to Hito Steyerl’s In Free Fall, especially for bringing to my attention the citation of Sergei Tretyakov’s essay in the film. I wish to express my gratitude to him.

Hito Steyerl, In Free Fall, video (color, sound), 32 min., 2010, 07:20–08:08.

Sergei Tret’iakov, “The Biography of the Object,” October, no. 118 (Fall 2006): 59, 62. As Fore notes, “This overhaul was not just a matter of enthroning objects at the center of the novel where the hero once was, for that would still leave the disproportionate and latent humanist structure of the novel intact.” D. Fore, “Introduction,” October, no. 118 (Fall 2006).

Tret’iakov, “The Biography of the Object,” 61.

Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image” e-flux journal, no. 10 (November 2009) →.

Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image.” The title of Steyerl’s first collection of essays, The Wretched of the Screen (2012), which includes the two pieces cited in this article, was inspired by Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth.

Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image.” In this regard, we should pay mind to the ambivalence of the title of the film In Free Fall. Historically, of course, it alludes to various events, including the stock market crash of 1929 in the US. In light of the formal and methodological aspect, however, it can also allude to creative destruction, that is, the possibility of generating new horizons and types of visuality. As Steyerl writes, “While falling, people may sense themselves as being things, while things may sense that they are people. Traditional modes of seeing and feeling are shattered. Any sense of balance is disrupted. Perspectives are twisted and multiplied. New types of visuality arise.” See H. Steyerl, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” e-flux journal, no. 24 (April 2011) →. On this subject, see also Paolo Magagnoli, “Capitalism as Creative Destruction: The Representation of the Economic Crisis in Hito Steyerl’s In Free Fall,” Third Text 27, no. 6 (2013): 723–34.

Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image.”

Category

Subject

Translated from the Russian by Thomas Campbell.