Daniel Birnbaum: Seventy-nine artists is a relatively limited number.

Ralph Rugoff: How many did you have in yours?

Daniel Birnbaum: I can’t remember.

—Artforum, May 20191The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up, 1936

In his statement inaugurating the 58th Venice Biennale, Paolo Baratta, its president, felt compelled to address the image of the event. Entitled “The Visitor as a Partner,” the statement reads in part:

A partial vision of the Exhibition might consider it a high-society inauguration followed by a line six months long for “the rest of the world.” Others might consider the six-month-long Exhibition the main event and the inauguration a by-product. It would be so useful if journalists would come at another moment and not during the “three-day event” of the “society” inauguration, which can only give them a very partial image of the Biennale!2

It would be useful, indeed, but it won’t happen.

“Our visitors have become our main partner,” Baratta candidly adds (meaning “commercial partner”), to such an extent that during the overcrowded opening days, many artworks were at risk of being damaged, and basic health and safety standards weren’t followed. Everyone entering the Biennale had to display their ID along with their invitation; each one of us was expected and registered. But it wasn’t hard to understand that the interminable lines weren’t exclusively made up of journalists, to whom the opening days are supposedly dedicated. Other categories of professionals have been able to get ahold of tickets in very large numbers, and we learn from Baratta’s statement that it wouldn’t be possible to do things otherwise. To justify this decision, Baratta recounts a tale by Aesop involving an old father, his young son, and their donkey going to town:

The old man rides the donkey and the people passing by say “look at that selfish man, he lets the child walk on this horrible path, look at his poor little feet.” The father reacts, they switch places, and a new group of passersby say “look at that selfish boy, full of energy but he leaves his poor old father the fatigue of walking.” They feel a bit humiliated and decide to both ride the donkey together and the comment is “barbarians, that’s a true exploitation of animals!” Finally, they decide to both dismount, just in time to hear “look at those two idiots, they have a donkey and they’re walking!”3

Unsure if we were overburdening a donkey, or walking beside it when we should have been riding it, or occupying the place of the animal ourselves, something felt wrong at the opening of the 58th Venice Biennale—something besides the strangely wintery weather that made the fog in Lara Favaretto’s Thinking Head (2017–19), streaming from the facade of the Central Pavilion, completely invisible. At the main entrance, and in front of each pavilion, and spiraling around buildings and reappearing around corners, lines manifested a new sort of poverty of the privileged. In the early afternoon of the second day, it took perhaps twenty minutes to access a toilet in the Giardini—and that’s a conservative estimate. To get into the Lithuanian, British, and French pavilions, people had to wait over two hours in the chilly rain, making it impossible for them to see the rest. No exhibition can compensate for such suffering; the art often seemed not worth the trouble to see it. This year the format of the Biennale appeared particularly outdated, inhuman, absurdly monumental, and anti-ecological. For one, the national pavilions inside the Giardini were geographically organized according to the usual insulting geopolitical hierarchy that has now contaminated the Arsenale and the whole city of Venice. This year the United Arab Emirates resurfaced at the end of the incongruous escalator of the Corderie, while the Venezuelan Pavilion was left dramatically closed, with no signage or public declaration about it. The Golden Lion–awarded Lithuanian Pavilion, which featured Sun and Sea (Marina) by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė, had to crowdfund just to keep its doors open. It has since run out of money again.4

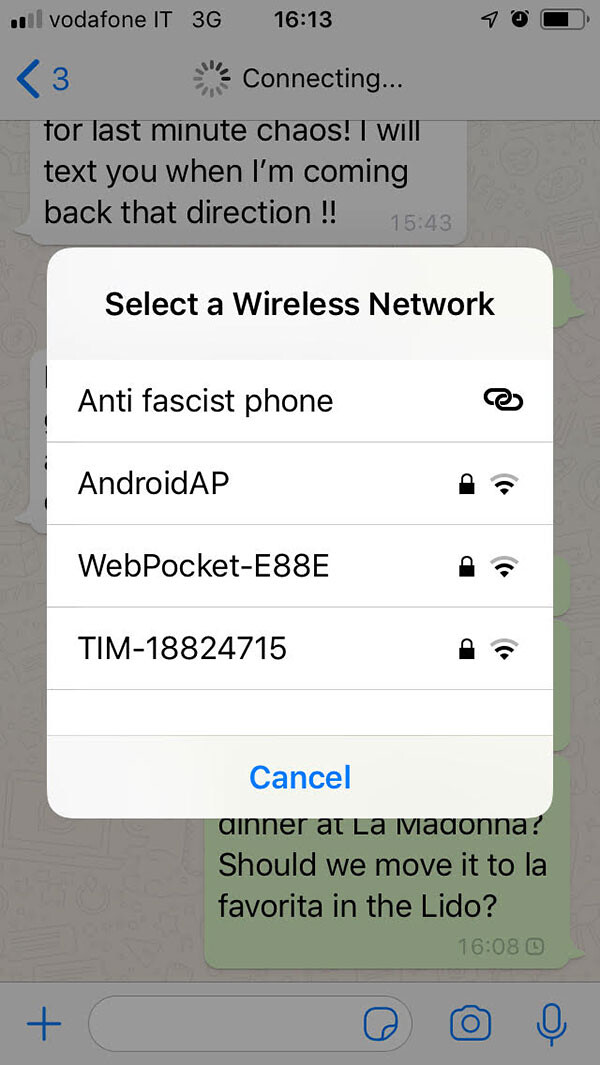

Cell phone screenshot of wifi networks outside the Scottish Pavilion in Venice, 2019. Photo: Claire Fontaine.

The times we are living in are indeed “interesting,” as the title of this edition of the Biennale states: they resonate with a city awaiting the verdict of the forty-third session of the World Heritage Committee, which will likely add Venice to its List of World Heritage in Danger. Venice’s livelihood comes precisely from what is killing it (biennials included): if tourism were regulated, the economic survival of the city would be at risk; at the same time, if it continues to impact the environment of Venice the way it does now, the jewel of the lagoon will soon be destroyed.5 There are other structural problems related to the ethics of giant exhibitions: accumulation, we all confusedly feel, is damaging for art in general and contemporary art in particular. The implicit equivalence that is made when such large amounts of artworks are simultaneously displayed by private and public institutions on the same limited territory is frightening. The very adjective “private,” when coupled with money, has become redundant: money belongs, at this stage of capitalism, to who makes it, because the very victory of capitalism lies in the defeat of any system of wealth redistribution. If this isn’t news, its effects on contemporary art are more pernicious than we think: displaying square kilometers of experimental gestures that took place at different moments and in different areas of the planet simply deprives them of the value that was given to them when they were selected.

At this year’s Biennale one could sketch a political history of fire and its traces as found in the works of Alberto Burri and Jannis Kounellis, from scorch marks to live flames, and then visit the desolate Pino Pascali exhibition (curated by his own foundation), where water is absent from the sculptures: his puddles are dry and empty cavities in the enameled tiles. Painting seems to better “resist” both accumulation and curatorial abuse; it is a “good-natured” form of art that tolerates most company and compensates for its historical gaps with the colorful community of the medium. (But what to do with Helen Frankenthaler’s majestic tactile abstraction while observing dozens of Sean Scully’s masculine striped canvases on display a short boat ride away? Someone must win or lose, especially in an atmosphere of prizes and Golden Lions, even if it’s left unspoken and the market prices of artists are no help in deciphering hierarchies.) The illegibility of large exhibitions is planned and not accidental, for this allows for more names to be included, for a more faint curatorial signature, and for an ambiguous political agenda. The truth is that only small and utterly focused exhibitions, in which capriciousness or opportunism don’t have a place and curatorial intentions are transparent, would be a faithful mirror of what the art space is, for its insiders and outsiders. Any lack of rigor or historical contextualization is just due to laziness and incompetence. But so far it looks like the contemporary art world has failed to educate its rich lovers. It has learned a lot more from them than they have from it. “May you live in interesting times” is a fake proverb quoted throughout history by countless people; Ralph Rugoff, who curated this year’s Biennale and devised the title, picked it as a wish and a curse. But Rugoff actually fears the fake news he seems to mock. “The internet,” he writes in his curatorial statement, “initially hailed by optimists as ushering in an era of free access to information, has proven to be an equally powerful tool for circulating both strategic disinformation and simple misinformation.”6 These days, when Assange is imprisoned after enduring years of “white torture”7 and Robert Mueller delivers a muzzled report, we can’t help but feel that there are probably more urgent matters than blaming the unverified content available online: propaganda pales in the face of the armed threats to freedom of speech.

“Books will be your prison, freedom will be your prison,” we hear in the deeply disturbing video Foucault X, one of the fictional and visionary narratives (other include Sade X, Casanova X) in Shu Lea Cheang’s 3×3×6, a vast video installation in the Taiwan Pavilion, curated by Paul B. Preciado in the Palazzo delle Prigioni. Joyfully pornographic and subtly disquieting, the work welcomes us with the warning that our images will be collected by two 3-D cameras and preserved by the artist after the show. Repression and the paradoxes of freedom in present times are the axes of investigation of her “trans punk fiction, queer and anti-colonial imagination hacking the operating system of the history of sexual subjection.”8

Is one’s sexuality a wild beast to tame, a desert landscape, a war zone? Is trying to look at one’s feelings with distance comparable to flying a drone over a wasteland? The movie by Charlotte Prodger in the Scottish Pavilion seems to give a positive answer to all these questions. Entitled SaF05, the movie is named after a lioness in Botswana who grew a mane and was never to be captured by the artist’s camera. The screenings are at fixed times, but during the opening days the pitch-black projection room filled up quickly, leaving outside long lines of people hopeful that boredom or a conflicting commitment would free up some space. Inside, the spectators bask in the light of a projector lying flat on the carpeted floor, enjoying the unthreatening nature of the cinematic exercise: white rocks and snowy mountains with no humans to be seen are a very relaxing sight after having been ceaselessly immersed in crowds. This meditation on desire, queerness, and time travel is strongly connected, we are told, to Prodger’s previous movies, which unfortunately we haven’t seen. (Rather than bookstores filled with gadgets, should each Biennale have a video and book library for viewers, to allow them to research the featured artists for the duration of the exhibition?) Prodger is a Turner Prize winner, like Laure Prouvost, who is representing France this year. In representing Scotland, Prodger succeeds Cathy Wilkes, who took part in the Scottish Pavilion in 2005 and this year occupies the British Pavilion, having also been a Turner Prize–nominated artist in 2008. It’s a small world but not an obvious one, because there is in the work of these three women a resolute un-monumental posture. With Wilkes’s exhibition we are under the impression that the format has heavily impacted her practice. Her shows are usually sparse, violently feminist, with small works hung at child height, putting the ready-made through a moral trial. Wilkes has a domestic economy to her art-making, and its results are usually moving, surprising, intense. This time the space was too austere, too lit, too martial to be dealt with. Her usual tenderness united with a sharp lucidity was nowhere to be found; the figures were shadows of their own sculptural presence and the paintings in the pseudo-domestic setup were to be read as independent works and parts of a decor. Everything was both a prop and a ready-made, a dead insect and a sculpture, an exhibition and its reluctant refusal, whilst the viewers kept dragging mud and leaves on the pale parquet that Wilkes had chosen as a neutral background for her minimal gestures. Wilkes (Irish by birth) has kept silent about her works. Words, she probably feels, would only hurt. (Some artists cannot “represent a nation,” and probably nobody should.)

In the Canadian Pavilion, an Inuit collective finds a brilliant and anti-colonial solution to this dilemma. They are called Isuma, meaning “thoughtfulness” or “to think” in Inuktitut, and consist of Zacharias Kunuk, Norman Cohn, Paul Apak, and Pauloosie Qulitalik. Isuma was founded in 1990 with the goal of preserving Inuit culture, language, and stories. The movie they presented, which plays on several large plasma screens—each subtitled in a different language—is superb. It’s shot in a wild location (northern Baffin Island) that’s so abstract and icy, it acts as an infinite white cube where the last Inuits not living on a reservation reside. The dialogue revolves around the institutional world of the character “whiteman” (actor Kim Bodnia), who represents the Law, the Canadian state, and colonial power. Entitled One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, the film is a visual experiment whose real protagonist is the violence of translation. The Inuktitut language, which Bodnia doesn’t understand, is the ground that the Inuit translator and Piugattuk use to resist his influence. His words are not faithfully repeated to Piugattuk by the interpreter, and vice versa, because translating means showing the forces at work inside a language and not just mechanically relaying meaning from one idiom to an other. “He is always repeating the same thing!” objects the old Inuit man who wishes to continue living like his ancestors and refuses to abide by the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement of 1994. According to Isuma’s website, with this contract the “Inuit gave up Aboriginal Title to 83% of their land and 98% of mineral rights, in exchange for the largest indigenous cash settlement in history.”9 In the film, Piugattuk has left his igloo—bringing along family, friends, and dog sleds—because he was out of sugar. Bodnia gives him some, along with other goods, but the metaphorical bitterness that comes from the exchange with the non-native white man infects every gift with the taste of bribery. “Your kids will go to school, you will have money from the government, health care …” Like an indigenous Bartleby, Piugattuk would prefer not to. The movie’s documentary aspect is evident in the scene where Bodnia’s face grows red and his nose runs terribly due to the cold: what is an uninhabitable hell for white people is the Inuit’s world, a space made of smells, colors, signs, and flavors that we don’t recognize. The interior of Piugattuk’s igloo is covered with pages from magazines. The decapitated head of a walrus is in the kitchen and there is a small flame to melt ice for tea and keep the place warm. Nobody should have to give this up.

“Imagine a beach—you within it, or better: watching from above … Then a chorus of songs: everyday songs, songs of worry and of boredom, songs of almost nothing. And below them: the slow creaking of an exhausted Earth, a gasp.” So reads the text at the entrance to the celebrated installation-cum-performance Sun and Sea (Marina) in the Lithuanian Pavilion. After two-and-a-half hours spent waiting, we are eager to look at relaxed people in their swimsuits. The set is an artificial beach reminiscent of the urban ones that grow in the summer on the shores of polluted rivers in cities with no access to the coast—urban beaches from Paris to Berlin. The play that is performed is a tableau vivant and a metaphor, but somehow what we are watching from the balcony above is truly happening, the performers are really lying down, chatting, reading, walking dogs, and looking at their phones. Kids are playing and we are witnessing this staged leisure during a real planetary crisis. The amusing lyrics that they sing revolve around banalities such as stress and relaxation, greasy sunscreen and missed flights. Electric cables occasionally stick out of the thin layer of sand, and through the back windows the green lagoon is visible, adding a layer of complexity to the interior environment, which is artificially lit and kept warm by portable heaters. (When we were there in early May, the temperature in Venice was around 14° Celsius, ten degrees colder than usual.)

Climate change was the invisible actor in the play, and it was also present in many other works all around the Biennale. In Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS we hear Greta Thunberg telling us once again, “I want you to behave like your house is on fire,” over images of a flood. In the French Pavilion, Laure Prouvost’s Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre welcomes us on a resin floor looking like solid water encrusted with detritus and marine garbage. The entrance has been moved to the back of the building, where one passes through a messy storage area; we are told by a guide that the artist has dug a tunnel to the neighboring British Pavilion (to oppose Britain’s growing insularity). Prouvost’s movie is emotional and chaotic, filled with Franglais puns. It has the texture of what life after capitalism will be like if we are to witness it. The footage comes from a journey that starts in the Paris suburbs and ends in Venice, at the French Pavilion. When the voice-over describes what the extinction of a species feels like, and when the actors sing to the waves a song for the migrants lost at sea, we forgive every minor fault of the work. There were also performers and sculptures on the premises, but they were not as compelling.

In the Biennale for the first time, Ghana’s pavilion benefitted from its wonderful thermally insulated premises, designed by David Adjaye and built with the same earth used to construct buildings in Africa. In John Akomfrah’s Four Nocturnes, high-end technology is used to film the smallest details of plants and wildlife. At times one is under the impression of being plunged into a three-channel nature documentary, almost sensing the smells and the temperature of what one sees. But everything tells the tale of the planet becoming unlivable, and of migrants being treated like animals. We see people wearing elephant masks on their journey through a desert, right after witnessing the death of a baby elephant, his sibling trying to revive him over and over again, his family stroking his bones with their gray trunks when they later return to his grave. Neither Akomfrah nor Adjaye are from Ghana (other featured artists are), but the idea in Ghana Freedom is to convoke talent from the African diaspora, in order to celebrate the happy exception of the first African country to shake off colonialism.

There was hope in large amounts at the Chilean Pavilion as well: a solo show by Voluspa Jarpa entitled Altered Views, curated by Agustin Rubio. The pavilion is a meta-exercise, both more and less than an exhibition: formally, the solutions and inventions adopted by Jarpa are barely recognizable as coming from the same artist. We don’t have to like every part of it, although everything is, for one reason or another, likeable. The emancipatory opera, in which humor and tragedy find common ground amongst images of cowboys and lyrics about class struggle, colonialism, and social oppression, is a truly experimental work. The attention Jarpa devotes to revisiting the destabilization strategies of security services in South America, Italy, and elsewhere—displaying both classified and unclassified documents, showing how to access some of them online—is sorely needed. The videos about Chiquita bananas, the United Fruit Company, and the latter’s role in the Guatemala coup of 1954 deserve way more attention than we are able to give them here. These things are happening, Jarpa seems to remind us in countless ways, via multiple media—right here, right now, this minute. Hear the story! Tell the story!

Venice is also a city where historic movie theaters are turned into supermarkets with exhibition spaces on the side. Kenneth Goldsmith was showing his work HILLARY: The Hillary Clinton Emails in the former Cinema Teatro Italia, now a Despar supermarket. A text pile made of double-sided, rainbow-colored printed paper, the work displays all the emails sent by Hillary Clinton from the domain clintonemail.com between 2009 and 2013. Over sixty thousand pages removed from their ghostly status as online documents have become the material of an uncreative poem. In addition, projections by several artists whose work appears in the UbuWeb database reactivated screens hanging over the checkout registers.

The closed Venezuelan Pavilion, Venice Biennale Giardini, 2019. Photo: Claire Fontaine.

Counter-narratives flow and leak like unstoppable high waters despite the Mose—this technological monster is portrayed in Hito Steyerl’s semicircular video installation at the Giardini. Realized in the liquid aesthetics of recent apps that turn photos into unstable painterly things, we hear the screeching sound of the dam supposed to save Venice, like a myriad of screaming seagulls. Entitled Leonardo Submarine, the video installation features a robotic Italian voice telling us how Da Vinci kept secret his invention of an ancestor of the submarine, afraid that it would be used as military technology. Steyerl’s piece in the Arsenale, This Is the Future (everybody has two separate works in Rugoff’s exhibition), makes us enjoy the company of electronic flowers that have superpowers, in a hilarious and smoky dark room. A video projection on a transparent screen informs us that the risks of entering the future for the human species are rather high, and we should seek help from the vegetable kingdom.

On offer at this year’s Biennale are many visual examples of thinking outside the box—among them the thrilling contributions from prize-winning Arthur Jafa and his long-time friend and collaborator Khalil Joseph. Joseph’s BLKNWS, a pair of two-channel videos made of found footage and occasional conversations staged in the studio, are mesmerizing. We tried several times unsuccessfully to leave the bench while watching it in the Giardini: we were hooked. The graceful balance between political and ecological (bad) news and hopeful and tender footage of black lives makes for an irresistible cocktail. For the white Westerners who make up most of the audience, it’s hypnotizing to see black beauty and intelligence condensed in this hyper-politicized work in progress. There are familiar pop videos whose soundtracks have been replaced, making us feel that when it comes to “news,” the bodies that are speaking don’t always talk with their own voices. We are also left wondering to what extent our fascination is a form of orientalism, and if we are the right receivers of these narratives. But Jafa’s work, a video called The White Album, has twists and turns that wake us from this oneiric state. Being black, as much as being white, isn’t a condition related to an origin or a race; it’s a relational reality whose complexities need to be explored. (Many black experiences and voices are present in multiple remarkable exhibitions throughout Venice this year, including AfriCobra’s Nation Time, which features amazing documents from the Black Arts Movement.)

The White Album tests our level of wokeness in its exploration of the fiction of whiteness as such, causing us to be uncomfortable, scandalized, and at times disoriented by our own image. That Jafa was awarded the Golden Lion for Best Participant was good news. So was the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement awarded to Jimmie Durham, somehow removing the focus from the stormy controversy about his Cherokee origins and highlighting his remarkable work. The Special Mention awarded to Teresa Margolles was also well deserved. (Although art prizes are all absurd, and their sole function is to send a political message.) Margolles’s works in Venice this year were different from her What Else Could We Talk About?, featured in the memorable Mexican Pavilion from ten years ago, curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina. No fluids from corpses or objects from morgues are on site. This time her materialist approach uses architectural fragments to make us feel the way women’s bodies move through and are endangered in public spaces that exist at the limit of formal political rights. Margolles’s La Busqueda (2) (2014) is a series of glass panes, taken from the city center of Juárez, Mexico, covered with posters of missing women, accompanied by the modified noise of a train recorded near the tracks that divide the city. In addition, a section of a wall from Juárez from 2015, covered in bullet holes and surmounted by razor wires, gives the ready-made a deeply political dimension in times where borders are more and more deadly everywhere.

There are a lot of paintings in Venice this year, figurative but also abstract, surprisingly all by women (some excellent canvases by Julie Mehretu stand out). This year Venice is definitely female and feminist.

That said, there is also a lot of digital animation made by men. When entering the Arsenale, the video game–like sounds emitted by these works give you the impression of having walked into a dystopian video-game arcade. Alex Da Corte, Ed Atkins, and Jon Rafman have very different approaches and research fields, but the retinal joy of watching adult cartoons must have been decisive for their selection. Pleasure is key to Rugoff’s curatorial strategy. “Artists have different ways of entertaining us,” he says, “and different ways of playing.”10 In Rafman’s Dream Journal 2016–2019, there is a profoundly disturbing moment where a child is using the same virtual reality mask that Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster invites us to wear to experience his Endodrome, also on display in the exhibition (but we can’t experience it because the line is, and will possibly always be, too long). The child is on the deck of a boat crossing a dead ocean full of garbage. On the same deck there is a drunken, vomiting creature. None of this appears in the visions of the boy, who in his head is running through a meadow and walking amongst enchanted lunar ruins. At some point he lifts his hand and all the chiromantic symbols float above his fingers. Then we see him from the outside, sitting on a bench in squalid surroundings, aimlessly moving his hand in the air. For a moment we realize that the child is an allegory of ourselves, transfiguring the apocalypse whilst watching an animation, sitting in a dark room in a dying city.

That’s why the awakening that grabs us when in the presence of Christoph Büchel’s installation Barca Nostra becomes so important in this context. The polemics raised by Büchel’s gesture (the exhibition of the wreck of a ship salvaged by the Italian government from the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea in order to identify the corpses of the migrants who died in it) are more thought-provoking than the work itself. Every single objection against it has the aim of preserving the art space from the violence of reality: people refuse to be surprised by the nonnegotiable evidence that the migrants’ tragedy isn’t made of images and words but of real rusty vessels and the drowned bodies of those who didn’t manage to escape hell. The news can be subconsciously dismissed, but metal can’t, judging by the reaction to Barca Nostra, and this gives us hope in the future of sculpture and conceptual art. The criticisms of the piece stem in part from the fact that the gesture was expensive. It’s in fact the only artwork whose production budget seems to interest journalists, although it’s not for sale, because the ship is a “monument” whose purpose is to remember the suffering of migrants, and it belongs to the Italian government. The artist has only moved it from Augusta, Sicily, where it is usually located. The act is deemed “cynical” supposedly because it comes from a “privileged” position11—as if any of the artists featured in the Venice Biennale wasn’t enjoying privilege and thriving in one of the most competitive professional fields in the world. Eschewing political correctness, Büchel is systematically cultivating the unease that contemporary art can still produce. His detractors would probably prefer the artwork to be authored by a Libyan or an African artist. If this is the case, we should rather ask ourselves why we want our art space to remain reassuring, why we want to bathe harmlessly in its privilege and deem it abusive whenever it wanders into troubled waters. What is exactly the breach of the secret etiquette that Barca Nostra is accused of? The answer might be more disturbing than the artwork and its history. The people who died in the Mediterranean and continue to die despite the efforts of militants, NGOs, and charities are not the only devastating losses we are accountable for. Something has also died inside us and continues to die. That’s what Büchel is trying to tell us.

Ralph Rugoff, “Double Vision,” interview by Daniel Birnbaum, Artforum, May 2019 →.

Paolo Baratta, “The Visitor as a Partner,” statement included in press kit for 58th Venice Biennale.

Baratta, “The Visitor as a Partner.”

Taylor Dafoe, “It Costs a Whopping $3 Per Minute to Run the Venice Biennale’s Universally Acclaimed Lithuanian Pavilion. Now Organizers Want You to Help,” artnet news, May 31, 2019 →.

After recent incidents involving cruise ships, they have been banned from entering the center of the city, where their imposing presence is both dangerous for people and destructive of the landscape. See Philip Pullella, “Venice Must be Put on U.N. Danger List, Ban Cruise Ships: Conservationists,” Reuters, June 24, 2019 →.

Ralph Rugoff, curatorial statement included in press kit for 58th Venice Biennale.

Wikipedia: “White torture is a type of psychological torture that includes extreme sensory deprivation and isolation. Carrying out this type of torture makes the detainee lose personal identity through long periods of isolation” →.

From the brochure for Shu Lea Cheang’s 3×3×6.

See →.

Rugoff, “Double Vision,” Artforum.

Alexandra Stock, “The Privileged, Violent Stunt That Is the Venice Biennale Boat Project,” Mada, May 29, 2019 →.