The whole problem consists in anticipating the anticipations of others, in singularizing oneself by imitating everyone before everyone else does, in guessing the “equilibria” that will emerge from cyberpsychodramas played out on a global scale.1

In July 1998 I produced an exhibition at the Villa Arson in Nice with a deliberately unspeakable title: “Post Discussion Revision Zone #1–#4. Big Conference Centre 22nd Floor Wall Design.” The exhibition comprised the removal of all the temporary walls from the main exhibition space of the Villa and the execution of a large geometric spiral wall painting in orange and brown on two walls. At each corner of the room hung a “discussion platform”: a 240 cm × 240 cm framework of anodized aluminum with transparent orange and light blue Plexiglas. People walking into this large space—four hundred square meters— gravitated towards the “discussion platforms” and tended to spontaneously gather under them, surrounded by the deliberately a-profound graphic resembling the Ancient Greek meander motif. Visitors tended not to look at the work or necessarily talk to each other. They were perfectly alone-together in a zone preordained for some kind of enforced exchange.

The entire structure of the exhibition in Nice was intended as a soft-warning on the question of who controls the center ground of social and political life in a postrevolutionary program of developed postmodern consensus. It was one of many mise-en-scènes realized in exhibitions and collaborative projects between 1995 and 2000 that I initially referred to as “What If? Scenarios” in exhibition titles and associated texts. The term was a self-conscious parody of the new applied postmodernism of rebranding and future speculation as business model. The earliest exhibition structures were in advance of the publication of a book provisionally titled Discussion Island/Big Conference Centre. The book took the form of a speculative fiction set in the near future where three characters negotiate endless rebranding, conciliation, compromise, and discursive subjectivity, all taking place in highly designed non-places of pseudo exchange. At the outset, the draft of the book suffered the same problems as a great deal of speculative fiction in that it had no convincing location for action; rather, the characters were stuck describing their conditions to each other, in the manner of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward or B. F. Skinner’s Walden Two. The exhibition structures—such as the one at the Villa Arson—were developed in order to provide a concrete series of settings for the book. The mise-en-scènes furnished an aesthetic prior to analysis and detailed action—something that could be described and acted upon with an awareness of a certain cinematic aspect where the setting itself can drive a narrative. This deliberate switching of cause and effect, point of reference and analysis, was intended to find an aesthetic frame for a state of affairs increasingly subject to rapid inversions of value and meaning. This was a period of rapid rebranding—new Ancient Greek–sounding names appearing within ambient ambivalent spaces of exchange as a replacement for more difficult and directly contestable activities or scandals: Altria, Aga, Areva, Avaya, Aviva, Capitalia, Centrica, Consignia, and Dexia were joined by Acambis, Acordis, Altadis, Aventis, Elementis, Enodis, and Invensys. By 2001, Arthur Anderson Accounting had become Accenture and Philip Morris had rebranded itself as Altria—all in an attempt to reflect the potential of new global markets and unforeseen opportunities, carried by new names that could be associated with visual affects spinning free from concrete associations.

The first line of Discussion Island/Big Conference Centre set the scene—a new space of conference centers, rebranding, and aesthetic misdirection masking trauma and pain: “However hard you try it’s always tomorrow. And now it’s here again. Across the other side of town, trauma had overwhelmed personal exchange. Something self-willed and determined had cut through the dusk. Pain in a building. We all called it The Big Conference Centre.”2

My nineties-era depiction of a world of endlessly mediated exchanges did not propose an origin or a series of didactic or documentary paper trails. It only pointed forwards. I needed new tools to understand the location of a starting point. Standard postmodern accounts of contemporary art seemed insufficient to cope with the ravages of the Thatcher and Reagan period during the 1980s and 1990s—to a young person, the writing seemed too formalist and overly obsessed with signs, signifiers, irony, and allegory, a bit like a Homeopathic Emergency Room trying to cope with the mass arrival of victims of a bus that had been driven off a cliff. There was a widening gap between the traditional art exhibition as a form and its newly emerging critical double: the product of curator(s) working alongside the artist to investigate the possibility of a new form of exhibition that questioned all aspects of display, mediation, experience, and communication. A sequence of projections, situations, and “films in real time” were produced by a number of artists at this time in an attempt to realize the near-future aesthetic conditions—Philippe Parreno and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster were certainly convinced of this new cinematic affect in the early 1990s. This was an effort to aid and offer structural support to collapsing models of resistance and collectivity that were being outmaneuvered, picked off, and co-opted by the accelerated rebranding and blurring of corporate and public life following a period of rapid capitulation. It was not an attempt to replace more urgent direct action or political urgency but to make a contribution by taking apart the aesthetic framework of the new neoliberal consensus. Was there any way to deal with the semiotic calamities of the years since 1968 other than via self-conscious reference to the various failures of applied modernism and their imminent co-option? One option was to at least unveil the deceit at the heart of the new belief in “transparency.”

Looking back at that period from the present, it would have been useful to know the writings of Gilles Châtelet at the time. He only appeared to me recently in a footnote on page 225 of the book 30 Years after Les Immatériaux: Art, Science, and Theory edited by Yuk Hui and Andreas Broeckmann. There it was: “See G. Châtelet, To Live and Think Like Pigs: The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, trans. R. Mackay (Falmouth and New York: Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014).” What the hell was this book with such a great title? And how had I missed it? It would prove—in part—to offer some of the essayistic and fantastical accounting of the period between 1968 and 1998 that I had been missing and that had not been effectively accounted for in earlier attempts to shoehorn the new self-conscious postmodern art practices into their various allegorical and ironic frames.

To Live and Think Like Pigs was published in French by Gallimard in 19983 but did not appear in English until 2014. The first chapter of the book is set in 1979, twenty years before its publication; now we are twenty years on from the point it was first published in French. These twenty-year jumps offer distinct periods, in terms of technology, the social, and the constitution of shifting mainstream political constellations. The twenty-year step offers indicators and markers of the social and its bounds that identify points of change more effectively than thinking in terms of decades. Twenty years is enough time to understand the development of a new technology through to its application. Twenty years is enough time for new educational models to take effect—both negatively and positively. Twenty years is still enough time to wonder whether a set of ideas within the art context retains any relevance or needs reconsideration. Twenty years was also the basis of earlier avant-garde promises and speculations. Duchamp believed that an artwork should only have a twenty-year life span.4 In the same interview where Duchamp says this, however, he asserts that language in the form of literature lasts longer since it takes longer to mutate; this statement is clearly open to contestation as we become more conscious of linguistic power structures, yet the provocation and its implications about art and its value over time remain under-quoted, and they have certainly resonated with me. It is maybe the reason why my entire project at the time circled around a yet-to-be-written book that would be exchanged cheaply and easily under the guise of a novel.

To Live and Think Like Pigs is an account of two dominant ideas from the 1990s that have now, two and three decades later, become markers of crypto-freedom in the hands of global data boys and have led to tragic inequalities of movement. It is a book against the way chaos theory, nomadism, and anemic underdeveloped concepts of difference were used throughout the 1990s as an enlightening model—and against poorly deployed mathematics-as-theory in general. To Live and Think Like Pigs is an account against a nomadism that appeared as a liberatory metaphor at the end of the twentieth century, yet in the twenty-first has become a dominant model of the cultural class in permanent motion, and a concomitant growing underclass penned in and restrained. It is a book against the “rational” individual as human data unit. It is against the political “market.” It is against the self-policing of all aspects in life. It predicts the envy culture of “rhinoceros psychologies and reservoirs of the imaginary for the pack leaders of mass individualism” (89). And roundly mocks them. And in so doing, also roundly mocks our 2019.

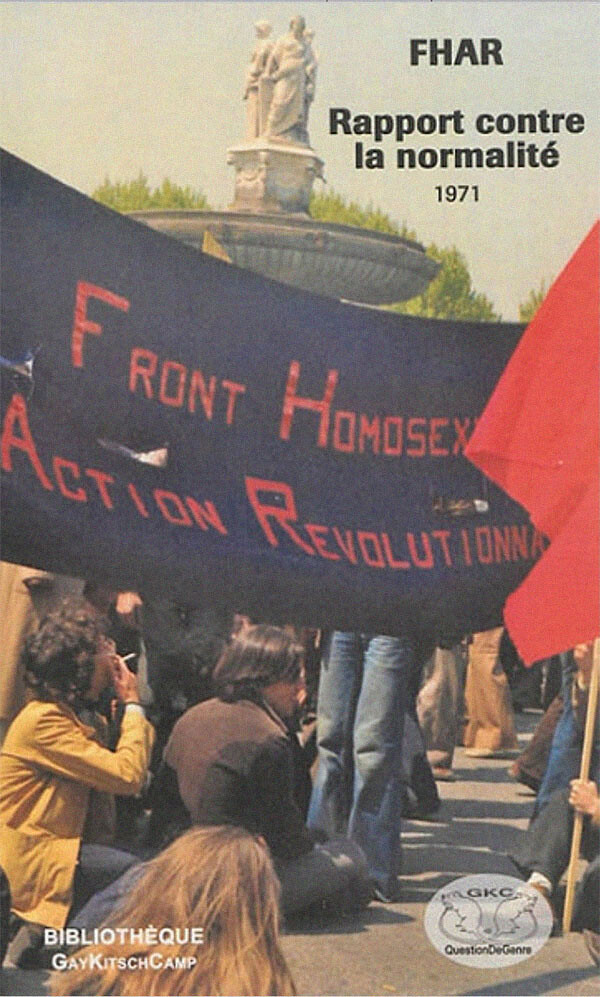

Cover of the book Rapport contre la normalité, 1971: le Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire rassemble les pièces de son dossier d’accusation: simple révolte ou début d’une révolution? Le Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire rassemble les pièces de son dossier d’accusation (2013), a book based on the original 1971 report by FHAR (Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire).

A late chapter is titled “The Fordism of Hate and the Resentment Industry.” What a perfect heading for the diminished social fabric of our time. The creation of a permanent underclass. The transfer of resources and capital from poor to rich. The isolation and abuse of those who do not conform to standard models, and most importantly the acceleration of technological surveillance under a voluntary code of data submission and self-policing:

The Gardeners of the Creative had basically sought to play Nietzsche against Hegel, and often against Marx. But they had chosen the wrong target: it is neither Hegel’s owl nor Marx’s mole, nor Nietzsche’s camel that surprises us at the turn in the road: it is Malthus, peddler of the most nefarious conservatisms, always smiling and affable, who stands watching the suckers haggling over the libertarian gimcrackery of nomadism and chaotizing (24).

Let it be understood, first of all, that I have nothing against the pig …

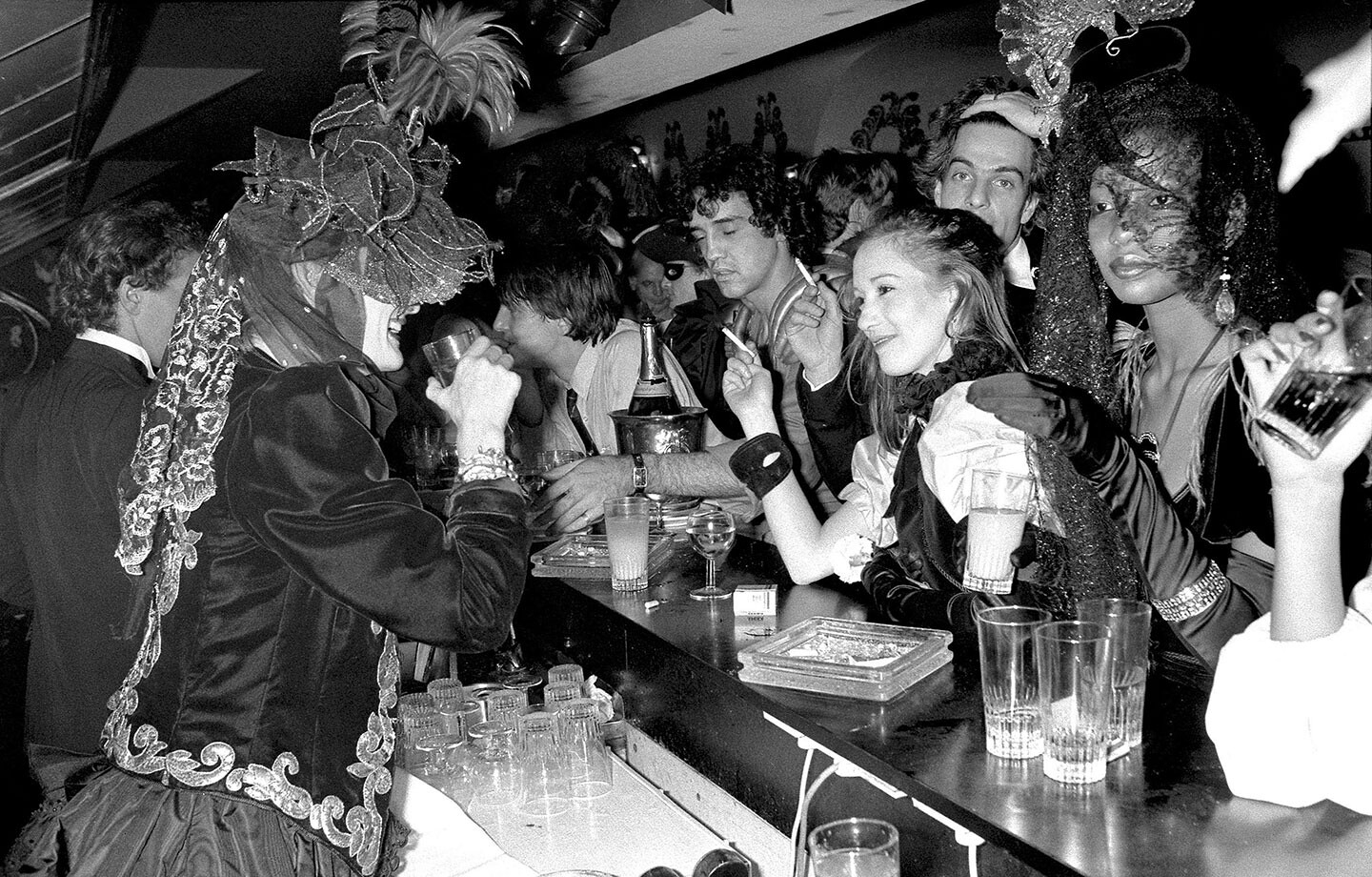

Thus begins Châtelet’s preface (1). The book itself opens in a nightclub. It is a Sunday night in November 1979 and “no one” who claimed to be anyone “wanted to miss The Night of Red and Gold” (11). A specific set of characters who appear to be all male and all in control of some aspect of their lives have come together. The Four Tuxedos and The Cyber-Wolves are key players among a “pool of beautiful, available, and arrogant suburban hounds” (14). All of these well-dressed hounds and wolves are hosted by nightclub “master of ceremonies” Fabrice and his “truculent collaborator,” the Red Glutton (13). Fabrice is our witness and the one who can see what is taking place while not gauging the full import of the moment. Even so: “He could sense how unstable was the cocktail of Money, Talent and the Press—as finely poised as the physicist’s famous critical point where gaseous, liquid, and solid states coexist” (18).

The opening scenario at the club’s Night of Red and Gold in ’79 points us towards our current conditions of exchange. It is a place of display and anxiety where tensions are overwritten by a collective signaling of potential and progress masked by new lifestyle allegiances. As Gilles Châtelet said in a 1998 interview:

It’s a book about the fabrication of individuals who operate a soft censorship of themselves; on the construction of what I call yoghurt-makers, of which Singapore is the typical example. In them, humanity is reduced to a bubble of rights, not going beyond strict biological functions of the yum-yum-fart type … as well as the vroom-vroom and beep-beep of cybernetics and the suburbs (the function of communication).5

Typical of the book itself, this quotation needs reading a few times for the vitriol to settle. Is Châtelet condemning the new City States of Globalization? Absolutely. Is he questioning the emergence of a new virtue-signaling isolated to the privileged and a-profound? From our perspective, there might be troubling implications here, but I do not believe he is going against real change and difference but rather a new constellation of eco-consciousness driven by the what would become the mature internet. It’s a snobby quote but an important one to indicate a new nationalistic form of development—the artisanal and the local powered by devices making claims for freedom that will not be able to fight off the self-censorship that will ensue. Châtelet’s book is raw, sharp, and unchained to the point where we are eventually dragged through a towering spiral of argument that slashes wildly at the emergent “realism” of the late postmodern consensus: “Pathetic young snobs trying to keep afloat in what already could only be called post-leftism! … with their ‘let’s not kid ourselves,’ their ‘it really resonates with me,’ and above all their ‘in my opinion, personally” (17).

… that “singular beast” with the subtle snout, certainly more refined than we are in matters of touch and smell …

I want to focus on the nightclub. The subtitle of the book is The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies. This is the site where the emerging class of super-self-conscious agents of narcissism are first introduced to each other in advance of their ultimate collective dividualization and envy-laden accommodation within the neoliberal “counterreformation.” By taking us clubbing, just ten years after the uprisings of 1968, Châtelet locates the conditions of envy and boredom in a pre-digital zone where people still come together yet are already rehearsing their roles as “Gardeners of the Creative.” The high-class Tuxedos are confronted by the pioneers of a forthcoming digital age. The coworking spaces and digitally shared envy-loathing of our present are pre-formed yet still surrounded by a protective bubble of excessive and hedonistic expectation.

The club is the setting—it is not the cause. It is the place that is open to identifiable proto-groupings—not only the Tuxedos and the Cyber-Wolves, but the whole mix typically found in a nightclub, from suburbanites to bankers, and opportunists who congeal in a lush swarm that pounds its way through the night. This is a particularly French nightclub of the 1970s, emerging in parallel to those in New York but with an interclass tradition of its own—even if a certain group of international celebrities attended both, from Warhol to Jerry Hall and Serge Gainsbourg, alongside a combination of the faded aristocracy, political operatives, suburban party people, and the emerging new entrepreneurs of the self. In the words of Fabrice: “Anyone who had not known the end of the 70s would not have known the sweetness of life, the thrill of this seesaw where History teeters between an old regime and the roar of a Revolution” (15).

The role of the club here is doubled and complex. It is the site of initial recognition across the crowd of the twinned drivers of the hyper-malaise to come—the Tuxedos and the Cyber-Wolves, the jaded pseudo-bourgeoisie and the energized proto-digitalists. At the same time it is still peopled by a mass of hedonistic potential that is driving and plenishing the master of ceremonies Fabrice, for he is still excited by this blending on the nightclub floor: “Shouldn’t a Prince of the Night be capable of making age groups, generations and social categories bear fruit by interbreeding them and seminating them with looks?” (15).

But let it be understood also that I hate the gluttony of the “formal urban middle class” of the postindustrial era.

First demonstration of the Marche nationale pour les droits et les libertés des homosexuels et des lesbiennes (Paris, April 4, 1981) by the Comité d’urgence anti-répression homosexuelle (CUARH). Photo: Claude Truong-Ngoc/Wikimedia Commons CC-by-SA-3.0

Starting in 1969 Châtelet was an activist in the Front Homosexuel d’Action Revolutionnaire (FHAR). A revolutionary movement founded in 1968, FHAR offered new forms of resistance to the dominant culture—including to the heteronormativity of the traditional and revolutionary leadership on the left. In his essay “The Spirit of May ’68 and the Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement in France,” Michael Sibalis relays an anecdote demonstrating the French Communist Party’s pathologizing of homophobia:

Jacques Duclos, Secretary of the French Communist Party, once upbraided FHAR militants: “You pederasts—where do you get the nerve to come and question us? Go get treatment. The French Communist Party is healthy!” Trade Unionists, Socialists, Communists, Maoists, or Trotskyists all looked askance at the Gay liberationists from the FHAR who joined their annual May Day march in 1971.6

FHAR members found political urgency by scandalizing both the bourgeoisie and the North African Arab areas of Paris—turning up in high-class places such as Café Flore as often as they appeared at the cafeterias of the banlieue, dressed in “bathing suits and tottering on high heels with hair on our legs.”7 By the mid-seventies Châtelet was drawn towards the explosion of new gay clubs in Paris, starting along the Rue Sainte-Anne.8 This means that To Live and Think Like Pigs is part autobiography—or more precisely, it draws upon Châtelet’s own observations of the nightclub as a location for ideological promiscuity and display. The tone of the opening chapter implies frustration, cynicism, and wonder in equal measure. It is quite possible that Châtelet would have known or encountered precise examples of his Tuxedos and Cyber-Wolves on his nights out. At the same time, he appears to be suggesting his own role as an implicated player in the nightclub as incubator of a new heterogeneity capable of being lured into a collective malaise of the future digital world of envy and boredom.

While the remainder of the book focuses on the broad erosion of revolutionary potential and the suffocating effects of neoliberalism, the decision to situate the opening chapter in a club is significant and written from this self-lacerating experience. Mohammad Salemy asserts in his “Intro to Châtelet” that “alongside his life as a scientist and an intellectual, Châtelet lived another as an unchaste party animal and, according to friends, was a fixture at La Palace, Paris’ response to New York’s Studio 54 and the allegorical setting of the book’s first chapter.”9

The nightclub is filled with “young condottieri of fashion, predators and headhunters … unforgiving to puppets who dare invoke any social hierarchy whatsoever” (11, 13). Anyone can be a citizen of the night. Among the crowd, Fabrice can spot The Tuxedos, “those who can hold aloft three generations of elegant parasitism” (12). But from the moment we first encounter the Tuxedos it is clear that something has changed and they no longer retain their class privilege and clear status. Although we meet them without any backstory or context, Châtelet makes it plain that they are becoming aware of their performative role, through which “finally they could adopt the modest, defeated tone of celebrities who, yielding to the crowd, had agreed to remove their disguises” (16).

On a couch opposite the Tuxedos sit the Cyber-Wolves. Fabrice and the Red Glutton stand aside and comment on their mocking exchanges. This is the meeting of those threatened by the new constitution of the night—with its dangerous mix of classes and identities, and those who see opportunity in an incipient emergence of individual desire and the banality of contemporary politics at the expense of combative revolutionary potential: “The neoliberal Counter-Reformation … would furnish the classic services of the reactionary option, delivering a social alchemy to forge a political force out of everything that a middle class invariably ends up exuding—fear, envy, and conformity” (19).

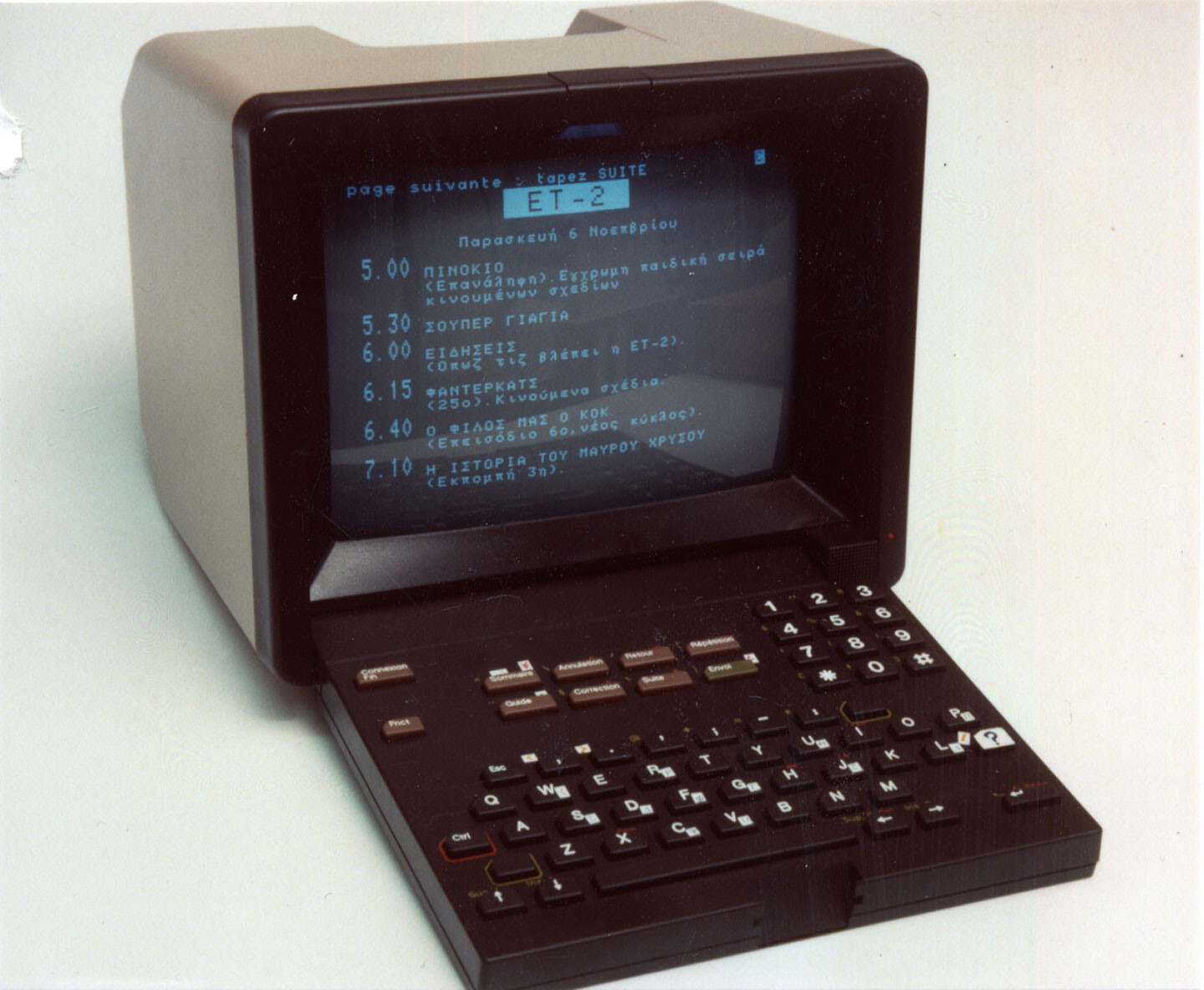

The Cyber-Wolves are the embryonic new-tech power class—they are a deluded group of preening arrogant nerds easily crushed by the Tuxedos in a last-gasp battle of class expression: “The Cyber Wolves, a quartet of young pedants prey to every trend … Like so many other suckers, the great goofballs of the cyber-pack thought of themselves as princes of networks and tipping points” (16–17). The evangelists for new technology. Those who promised a connected world to come where technology would contribute to the end of history and difference. Technological “amplification” would provide a universal market of the self and networks would allow the financial market to regulate itself.

A greek model of the Minitel computer, date unknown. Photo: Bernard Marti/CC BY-SA 4.0

It is at this point that Châtelet embarks on his turbulent narrative that boils over the rest of the book—each chapter addressing a different aspect of the implications he has laid out in the club, punctuated with turns of phrase, twisted points of reference, and wild ideas that startle the unwary reader who is more accustomed to a smooth flow and an uninterrupted thesis explication. For Châtelet, it is clear which way the initial nightclub exchanges are heading. The Cyber-Wolves and the Tuxedos along with Fabrice have been sucked into the eye of a coming storm. Partly thanks to the boredom and weariness of the former revolutionary thinkers, they are roundly losing their resistance and are about to be launched into the 1980s, with its effective and traumatic application of a counterrevolution of devastating power. “The reality check would come soon enough!” writes Châtelet. “It took less than three years to dissipate the charm and to assure the triumph of the 80s, with their nauseating ennui, greed and stupidity, the years of neoliberal ‘conservative revolutions,’ the cynical years of Reagan and Thatcher” (18).

Three key philosophical aspects from the time are opened up and gutted by Châtelet’s acid prose: difference, nomadism, and the attempt to “play Nietzsche against Hegel and … Marx” (24). For Châtelet, it is the anti-dialectical aspect of these three applications that render them so vulnerable to being co-opted, marketized, and manipulated. Torn out of a critical context, these constructions enter into an effective interplay with applied individualistic political theory and are subject to increasing market-based super-subjective misdirection. The book from this point on is a poison-pen letter to Châtelet’s contemporary intellectuals and mathematicians. It is a confession of having been witness to the birth of the conditions that directed consumption towards the self.

To Live and Think Like Pigs is about the marketization of every gesture, made possible by the accommodations that were made between increasingly cynical class actors at every level and the Ayn Randish pseudo-ethical nerd culture. Under the banner of personal liberty, this culture would come to feed on the individual as a source of data, maintained by envy and incited by boredom. Following our night in the club, an irreversible change has taken place. The capitulation to “rational expectations” is complete: “Now would come the era of the market’s Invisible Hand, which dons no kid gloves in order to starve and crush silently” (19).

While a surprising success in France, Châtelet’s book was unavailable in English and has been somewhat overlooked. If we had been more aware of it outside of the Francophone context, then the anger and complexity of Châtelet’s devastating account of the origins of our condition would have prepared us with frightening clarity and precision for what was to come. My own account missed the narcissism, nationalism, and collapse that has become a perverse conclusion of the neoliberal counterreformation begun by Milton Friedman et al., enacted by Thatcher–Reagan, and now conclusively pantomimed by Trump and the hysterically fabulist global strongmen of 2019 and their all-too-real and shocking new forms of nationalism. There would also have been fewer bad group shows about nomadism and chaos theory. A nightclub standoff between a weary aspirant consumer class and a group of Cyber-Wolves would have been a good astringent.

At the end of Discussion Island/Big Conference Centre—a book of rather meandering mise-en-scènes—a man suddenly jumps out of the Big Conference Centre window, landing on top of a Toyota. It is unclear whether the person has fallen, jumped, or been pushed. What I do know is that it seemed crucial to include this scene to indicate what I could not account for in the text. I may have been thinking of Deleuze or Debord, both of whom had recently taken their lives. Gilles Châtelet committed suicide in June 1999 while suffering from AIDS, one year after the publication of his powerful and moving plea for everything to be better and different and unbound from the predations of envy and boredom.10 I was not thinking of him.

Gilles Châtelet, To Live and Think Like Pigs: The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, trans. Robin Mackay (Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014), 133. Italics in original. All subsequent page references to this book will appear in parentheses in the body of the text.

Liam Gillick, Discussion Island/Big Conference Centre (Derry and Ludwigsburg: Orchard Gallery and Kunstverein, 1998).

Gilles Châtelet, Vivre et Penser Comme des Porcs: De l’Incitation à l’Envie et à l’Ennui dans les Démocraties-Marchés (Gallimard, 1999).

“There is life in a work of art which is short … even shorter than man’s lifetime. I call it twenty years. After twenty years an impressionist painting has ceased to be an impressionist painting because the material, the colour, the paint, has darkened so much, that it’s no more what the man did when he painted it. Alright. That’s one way of looking at it. So I applied this rule to all art—art works—and they after twenty years are finished, their life is over.” Duchamp interviewed by Richard Hamilton in London, 1959. Audio Arts, vol. 2 (1974).

See →.

Michael Sibalis, “The Spirit of May ’68 and the Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement in France,” in Gender and Sexuality in 1968: Transformative Politics in the Cultural Imagination, eds. L. Frazier and Deborah Cohen (Springer, 2009), 245.

Quoted in Sibalis, “The Spirit of May ’68,” 245.

Sibalis, “The Spirit of May ’68,” 245.

Mohammad Salemy, “Intro to Châtelet,” Third Rail Quarterly, no. 4 (Spring 2015) →.

“He was particularly affected by the death of Gilles Deleuze. Wondering how not to give the suicide of the latter the sense of an ultimate and courageous revolt of life against the spirit of resignation and ‘laissez-faire.’ AIDS sufferer, Gilles Châtelet probably had the feeling of facing the same challenge. He was 44 years old.” Marc Ragon, “Mort du Philosophe Gilles Châtelet,” Libération, June 19, 1999. Translated by the author.