Dum spiro, spero (While I breathe, I hope)

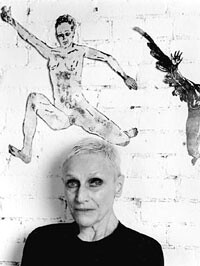

“The one thing that artists must possess above all other qualities is immense courage,” the filmmaker and anthropologist Jean Rouch once said to me. Nancy Spero, who died on October 18th in Manhattan at the age of 83, was a woman who possessed immense courage, both in her art and in her life. For more than half a century, this courage propelled a practice of enormous imagination that moved across painting, collage, printmaking, and installation, constructing what Spero once called a “peinture féminine” that could address—and redress—both the struggles of women in patriarchal society and the horrors perennially wrought by American military might. Nevertheless, Spero’s art was ambiguous and never merely illustrative, and her treatment of these subjects came through a complex symbolic language incorporating an extraordinary polyphony of goddess-protagonists drawn from Greek, Egyptian, Indian, and pagan mythologies. She once told me that “goddesses, as is true of the gods, possess many characteristics of the eternal, which range from the tragic to transformation into a state of pleasure or even extreme excitement or happiness.”

Her prolific and tremendously inspired career was also fueled by her enduring dialogue with Leon Golub, whom she met in the late 1940s as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and later married. In Paris, where they lived from 1959 to 1964, Spero produced a series of hauntingly oblique works called the Black Paintings, clearly infused with something of their mid-century Parisian, existentialist milieu. Painted at night and featuring androgynous figures and scrawled text fragments in somber colors over bright underlays, the artist once described them as “lyrical,” but also, “deathlike.” Throughout her career, Spero’s aesthetic was indeed one of the fragment, of the torn piece borrowed and fractured, the artist akin to Gilles Deleuze’s “vol créateur” who creatively steals and redirects meaning. Collage, though only one of the artist’s formal means, remained what we might call the conceptually determinant medium of Spero’s art.

Initially, Spero’s work was not openly confrontational—“not parallel, but at an angle,” she once said, paraphrasing Simone de Beauvoir. It was only with the War Series (1966–70), produced at the time of the war in Vietnam and after the couple had relocated to New York, that the terms for Spero’s subsequent overt politicization of painting were established. Its gendered bombs and helicopters, blood-spurting heads and flying insects, constructed a scatological picture of conflict as orgy. Its grotesque realism (in Mikhail Bakhtin’s sense) was all the more disturbing for what Spero once described as its “weird combination of the celebratory and the horrendous,” of the “festive and the frightening.” Kill Commies/Maypole, a work from the War Series that featured severed heads dangling from the end of maypole ribbons, was to form the basis—forty years later—of Spero’s thirty-five-foot-tall hanging mobile, Maypole/Take No Prisoners, installed in the entrance hall of the Italian Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale. The relation of repetition and difference between the two works paralleled that between the conflict in Southeast Asia in the 1960s and America’s recent war in Iraq, casting a “terrible continuum” of death and destruction into relief.

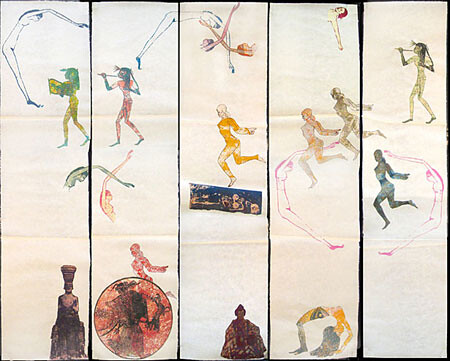

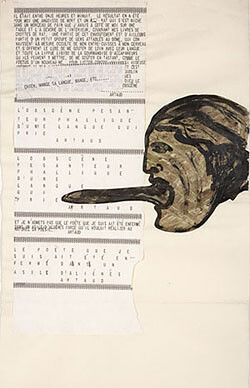

Spero specialized in the dissection of conflict. The series of scroll works entitled Codex Artaud that she created between 1971 and 1972 further used collage to produce startling juxtapositions of text and image, their horizontality and the linearity of their elements recalling hieroglyphics, the shards of text taken from Antonin Artaud’s writings exposing her “anger and disappointment at the art world and at the world as a whole.” By this time, Spero had become heavily involved in activist groups operating in and around the New York art world, joining the Art Workers Coalition in 1968 and Women Artists in Revolution in 1969, and becoming a founding member of the women-only cooperative gallery A.I.R. in SoHo. The empowerment of women artists through these activities found symbolic form in Notes in Time on Women, an encyclopedic work Spero first presented in 1979. Taking the form of a 210-foot-long scroll charting the status of women through historical time, it featured figures of athletic women, both ancient and modern, who hopped, skipped, and jumped among quotations from a myriad of sources, many of which spoke to both the implicit and explicit misogyny in the canon of male European philosophers.

From the 1980s onward, Spero exerted a powerful influence on younger generations of artists while continuing to be highly prolific herself. Many of her later works are defiantly hopeful and celebratory, a tenor reflected in her use of particularly strong colors during this time. For instance, a mural produced in the highly charged locale of Derry, Northern Ireland, honored the political actions of the city’s women with a frieze of Greek goddesses and contemporary athletes alongside images of Derry women, while in a 2001 mural on the walls of the 66th Street station in New York City’s subway we see the dynamic figure of an opera singer in a golden gown, lifting and lowering her arms in song beneath the Lincoln Center, home to the Metropolitan Opera.

Nancy Spero continued to work with this sense of hope, despite having suffered the loss of Leon in 2004 and problems with her own health, and amid the deepening of America’s political crisis and international injustices. Spero’s art was suffused with this very human hope, which she saw as being grounded in the intractability of human struggle. Her work was never crudely utopian—as she told me, “utopia, like heaven, is kind of boring.”

Beyond a body of pioneering and exceptional work spanning more than half a century of tumultuous social change, this sense of hope will be her legacy. It was an everyday hope that she lived and breathed, and a hope for today rather than tomorrow: “I don’t know about the future yet because everything is subsumed in the present.” She liked to quote Susan B. Anthony in saying, “Failure is impossible.”