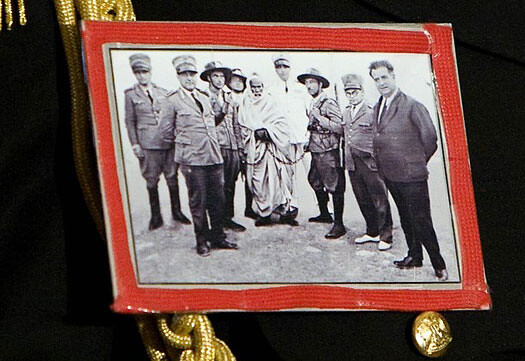

At the start of his official state visit in June 2009, revolutionary leader Muammar al-Gaddafi, meanwhile the world’s longest-serving head of state, gave the Italian audience a lesson in matters of colonial history. He had a slightly retouched black-and-white photograph pinned to his uniform, and the entire country found out that depicted on it Omar al-Mukhtar, leader of the Libyan resistance against the Italian colonial regime. The famous photo shows the nearly seventy-year-old man after his imprisonment in September 1931, shortly before his execution in the Solluch concentration camp near Benghazi. Fascist magnificos proudly present the sheikh in chains as booty for the camera.

On the second day, at the entrance to the Palazzo Giustiniani, which has housed the Italian Senate since 1926, a few senators from the opposition party, Italia dei Valori, protested somewhat haplessly against the Gaddafi visit and current human-rights violations in Libya by holding up for television cameras a photocopied image labeled “Lockerbie 270 Victims.” It was a press photo of the wreckage of the Pan Am airplane destroyed by a bomb while flying over Scotland in December 1988. The explanation for it: everyone has the photo they deserve. This Italian version of image war has a long tradition. New relevance was added when in the spring of 1994, after the first victory of a center-right coalition led by Berlusconi, footage taken in 1945 by U.S. army cameramen at Milan’s Piazzale Loreto was broadcast on television. In debates surrounding Combat Film, anti-fascists were forced to register with great frustration as the corpses of Benito Mussolini and Claretta Petacci were equated with the 335 civilians murdered by the Nazis in the Ardeatine Caves. On the other hand, in the mid-1990s came the first admission by an Italian government of the long-denied poison-gas deployment in Ethiopia.1

In Rome, Silvio Berlusconi also put his arms around the now eighty-seven-year-old son of the Libyan hero. Mohamed Omar al-Mukhtar had come along as part of Gaddafi’s entourage. Several days later, the pan-Arab daily paper Asharq al-Awsat published a telephone interview with him, “conducted under the supervision of Libya’s ambassador to Rome.” When asked if he believes that in the meantime all issues have been settled with the Italians, the elderly man answered, “Yes, of course. They are not how they were in 1911 under Mussolini. This is a new generation and we look forward to improved ties between Libya and Italy.” 2

Under Mussolini, in 1911? In the summer of 1911, young Benito Mussolini was still a socialist party functionary in Forlì and vehement critic of the campaign initiated by a nationalist elite and the liberal Giolitti government against the Ottoman Empire. The goal was to control the Mediterranean. At the time, Italy was a poor country with a high illiteracy rate and two small, rather unprofitable colonies in Eastern Africa: Somalia and Eritrea. Disastrous defeat at the hands of Menelik II’s army in Adwa had halted the greedy attack on Ethiopia in 1886. In a brutal war of conquest full of massacres and repression against the civilian Arab population, the Italians, with numerous Somali and Eritrean askaris in their army, took the two vilâyets Tripolitania and Cyrenaica as colonies.

There were excesses already in the first year, such as the pogrom of Shara Shatt in the vicinity of Tripoli, where thousands of Arabs were murdered within a few days. Thousands of prisoners were deported to the Tremiti islands or to Ponza, Ustica, and Gaeta. Also the first air raid in history, on November 1, 1911, was an invention of Italian colonialism. Lenin later made mention in one of his anti-imperialist texts of the “slaughtering of the Arabs with the most modern weapons.” The futurist Marinetti waxed enthusiastic about the “magnificent symphonies of shrapnel” in his war reports for the Parisian newspaper L’Intransigeant. It is certainly no wonder that Libya’s riconquista in the 1920s—the Fascists’ breaking of resistance and setting up of a regime of violence under Mussolini with even more modern weapons and methods—had transformed this era into a historical continuum. In the early 1930s nearly half of the population was deported from the eastern part of the country; there were sixteen concentration camps in the Cyrenaica region.

Yet what is more interesting about the little lapsus clavis in the interview is that in a post-democratic politics of images, it is as good as meaningless. This type of politics is not only successful in erasing history from the images, but is also entirely immune to competition from other images. The latter are not always difficult-to-identify victims or collateral damage of Italian trasformismo, but are in most cases themselves actors, accomplices, and voyeurs. Blind spots are often the more meaningful testimonials. When the young Masaccio painted his triptych of San Giovenale, he decorated the Madonna’s halo with the Arabic letters of the Shahādah, the Islamic profession of faith. Sacralized dead bodies, from Mussolini to Pasolini through to Aldo Moro, belong to national iconography just as much as the mafia victims photographed by Letizia Battaglia. Until now these have always been white bodies. But similar to the way cleric and archeologist Andrea De Jorio rediscovered gestures of classical antiquity in Neapolitans’ body language in 1832, evidence of the transmigration of political gestures can also be found.

In order to study the countryside and people, the painter Michele Cammarano spent some time in Eritrea. He was an acolyte of Garibaldi, an admirer of Courbet, and in Paris he met Proudhon (“property is theft”). In 1888, the Italian government commissioned from him a painting meant to eternalize the Dogali episode. Cammarano’s task was to reinterpret an Italian military defeat in the hinterland of Massawa with the loss of five hundred soldiers as a patriotic, heroic act. Piazza dei Cinquecento in front of the Stazione Termini in Rome is a reminder of it. When the huge painting was finally finished after years of work, on March 1, 1896, the battle of Adwa took place. It was the first and only time that an African nation succeeded in founding itself and defeating a European power. Adwa placed Ethiopia on the map of the modern world. The lost battle set off a political earthquake in Italy. On its first page, the New York Times published news of the stone-throwing mob chanting “Viva Menelik!” through the streets of Rome.3 Shortly thereafter, the government of Prime Minister Crispi had to step down.

Italian cities from Trieste to Palermo are full of reminiscences of the colonial past. There is Piazza Adua, Piazzale Gondar, Via Asmara, Mogadiscio, and Tripoli, and Viale Etiopia and Somalia. But after the Fascist era, Italy repressed and nostalgically falsified its colonial history. The loss of the colonies (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Libya, and also the Dodecanese Islands), sealed in the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947, was seen as unjust by the losers of the war. Remaining from colonialism, which disappeared with Mussolini, were sentimental tales of adventure, vacation experiences, and the vague sense that it had never really been serious. No one had to answer for the war crimes committed. While Ghana, Guinea, Tunisia, and Sudan proclaimed their independence, every ten days Africa parla published photo stories about African natives and Italian expeditions from colonial times. For a few years, even the Africa Ministry continued to exist. Until Somalia gained its independence in 1960, Italy was granted trusteeship of its former colony by UN mandate.

Under the slogan “You too can be like us,” the Americans sold their Marshall plan and colonized freed Italy. Bing Crosby and Gary Cooper came to support the anti-communist cause in the election. Democrazia Cristiana’s victory in the 1948 parliamentary election heralded a new era that would last twice as long as that of the ventennio and exactly as long as the Cold War. For people like Pasolini, born in 1922, there did not seem to be any major paradigm shift from what he called “traditional” or “archeological fascism.” He considered television, after it had completed the unification of Italy in the age of consumption, just as unbearable as the concentration camps. However, he knew: “What the bodies of our fathers experienced, our own cannot.” 4 Pasolini’s younger brother died in Friuli in a confrontation between feuding partisan groups. His unloved father returned from Africa after the war.

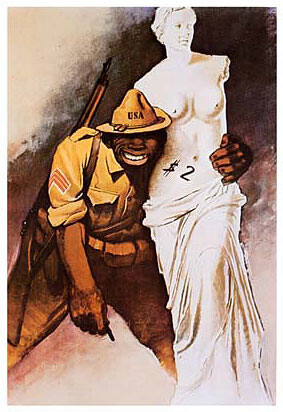

In the first famous postwar film, Rossellini’s Roma, città aperta, one finds a Catholic priest, a mother, a communist partisan, and the Nazis, but Italian Fascists are already missing. Rossellini, born in 1906, also worked on the Africa propaganda film Luciano Serra, pilota. In the second episode of Paisà (1946), a Neapolitan boy becomes acquainted with the African American military policeman Joe, who comes from an equally impoverished background. Neorealist rhetoric replaces racist propaganda that had shortly before celebrated its triumph with posters, such as the one of a black U.S. soldier stealing the white Venus de Milo and offering it for two dollars. Gino Boccasile, graphic designer of the Republic of Salò, created the poster. After a short pause, the result of capitulation and an inconsequential trial, he again found his way into the world of advertising. At first he made vignettes for Movimento Sociale Italiano, the neo-fascist party, and erotica. Then came posters for Amaro Ramazzotti, Yomo yogurt, Bianchi motorcycles, and Paglieri cosmetic articles.

Graphic designers such as Boccasile and Federico Seneca discovered the salability of the black body (“il caffè sono io!”) early on. Advertisements, posters, informational brochures, and exhibition displays, for the Milan Triennale, for example, served the goal of stirring a colonial consciousness in Italy.5 Postcards reaching a circulation of millions, with motifs oriented to men’s fantasies, added their contribution. An anonymous, bared Somali or Habesha woman was a new continent waiting to be discovered. Her smile promised that the capture would be worthwhile. The song “Faccetta nera” sang the praises of a beautiful little Abyssinian woman to whom the Blackshirts will bring another law and another king. “Kissed by our sun,” as a Roman, she, too, should march before the Duce and king. Until this time, Verdi’s Aida had been the most well-known Ethiopian slave.

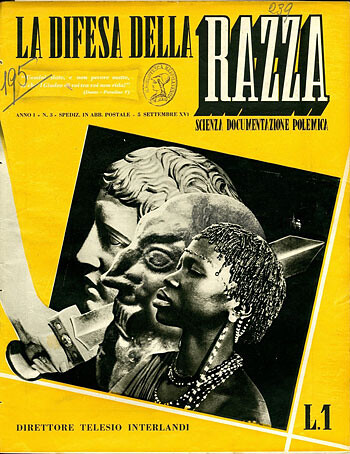

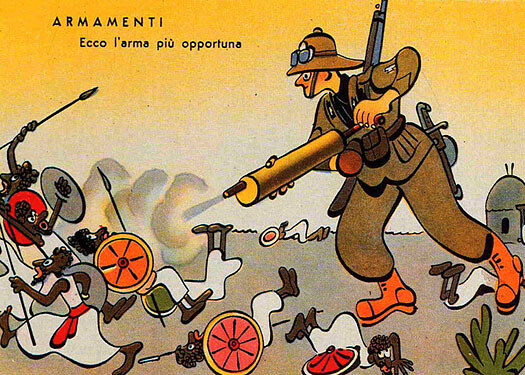

But the text of the cute black face and the pornographic photos were soon no longer suitable as heralds of the apartheid politics that the regime had decreed for the newly created empire. From 1938 to 1943, the magazine La difesa della razza became the most important propaganda tool for racial policies. Its rhetoric had no room for erotic reveries; instead, a sword divided Aryan Romans from degenerate others. A younger generation had the racist Pinocchio, version Pinocchio istruttore del Negus (1939), and the magazines Il Corriere dei Piccoli and Il Balilla, where cartoonists such as Enrico De Seta and Gustavo Rosso published their hate pictures. After the Allied liberation of Rome, De Seta drew caricatures of the GIs in Fellini’s Funny Face Shop.

Four decades after Adwa, Ethiopia was overrun by the Fascist war machinery. The Christian feudal empire had been the only country in Africa, other than the special case of Liberia, able to preserve its independence and avoid becoming a European colony. “Ethiopia” was a concept that inspired the pan-African movement and lent credibility to its religious leanings with Bible passages. The Ethiopian Manifesto (1829) by Robert Alexander Young identified all of the members of the African Diaspora as Ethiopians. J. E. Casely Hayford, a writer and lawyer born in the West African Gold Coast colony (today Ghana), contemplated the possibility of Jesus having had an Ethiopian mother in Ethiopia Unbound in 1911. Marcus Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and prophesized the crowning of an African king who would free the Black people. Red, yellow, and green were borrowed from the Ethiopian flag to become the pan-African colors.

End of June 1935, the heavyweight boxing fight between Primo Carnera and Joe Louis was staged in Yankee Stadium, New York City. From Los Angeles to New York, Afro-Americans took to the streets, donated money, boycotted Italian shops, organized acts of civil disobedience, and tried to volunteer for the war. The Duce stood behind the Italian Carnera, all of Harlem and Africa stood behind the “Brown Bomber” Joe Lewis. NBC and CBS refused to broadcast the fight on the radio for fear of possible riots in the cities. Louis knocked out Carnera after six rounds, but even he was not able to prevent the attack on Ethiopia. While Western governments succumbed to Mussolini’s blackmailing, protests erupted throughout the world in support of Haile Selassie and Ethiopia, comparable only with the wave of sympathy for Vietnam three decades later. In the cinemas of London’s West End, audiences applauded when the Ethiopian emperor appeared on the screen and booed the Duce and his two pilot sons. Time magazine voted the Negus “Man of the Year” in its January 6, 1936 issue.

After the capture of Addis Ababa, consensus between the Italians their Duce was at an all-time high. Mussolini declared the war to be over and the masses cheered the proclamation of the Empire on May 9, 1936, in Rome. Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia were united with the Kingdom of Italy as AOI (Africa Orientale Italiana). Among the few opposing voices was exiled communist Luigi Longo. In an article published in Lo Stato operaio he wrote, “We want the military defeat of Italian imperialism, because we love our country.”6

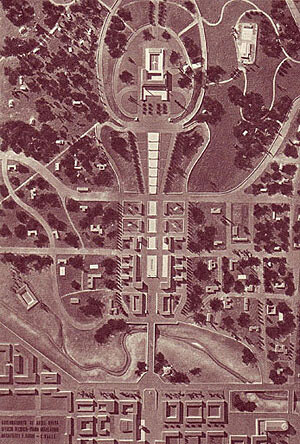

Mussolini’s empire was indeed short-lived, but it lasted long enough to export Italian architecture to Africa. Architects want to build. A propaganda film by the Istituto Luce called La fondazione della nuova Addis Abeba (1939) showed, along with the unrealized architectural models of government buildings for the new capital in AOI, how the architecture of apartheid functioned as a civilizing mission. First, people are driven out, then their old homes are destroyed. New suburbs, to which the Ethiopian population was relocated on the basis of ethnicity and religion, were set up for easy control and surveillance. They were conceived as settlements for cheap labor.

Le Corbusier also offered the Duce his colonial services and sent one of his “Ville radieuse” concepts, although without success. Gio Ponti likewise had to leave Addis Ababa with matters unfinished. In Domus, the magazine Ponti founded, Razionalismo ideologue Carlo Enrico Rava along with Luigi Piccinato were the main protagonists in the colonial architecture discussion. Rava’s father, “a Fascist with a diamond belief” according to Mussolini, made his career in Libya and became governor in Somalia in the early 1930s.7 Like Giuseppe Terragni, Rava was a member of the architectural association Gruppo 7. In the essay “Costruire in colonia,” he argued for a modernist aesthetic in the colonies and for precise knowledge of local conditions. The first and most important principle of urban planning is “the separation of colonial architecture into two parts, with indigenous people on one side and whites on the other.”8 Military and government buildings should stand in the city center as representations of white dominance and Fascist power. At the 1933 Triennale, Piccinato, who was involved in planning Sabaudia south of Rome in the Agro Pontino, presented his “Casa coloniale” destined for Libya. He developed prototypes, such as the two-story “Villa tropicale” for Eastern Africa. Italian propaganda considered it important to extol the colonies as tourist sites. Compagnia Immobiliare Alberghi Africa Orientale (CIAAO) opened new hotels in the larger cities. Ala Littoria, the national airline, offered regular flight connections and Gondrand busses traveled the roads whose courses Mussolini had personally sketched out.

At the 1940 Triennale, Rava presented design ideas for the colonies in the Mostra dell’attrezzatura coloniale. It was a melancholic product display of functionalist aesthetics, with pieces such as folding beds, plastic kitchenware, and hardy suitcases. Piccinato and Giovanni Pellegrini, who was working in Libya, were also involved in the designs. Special about Rava’s furniture in the “Camera coloniale” is that it was produced from chipboard and could be assembled quickly without nails, screws, or special tools, and could be transported in the provided crates. At issue was Italian culture asserting itself in “barbaric surroundings” rather than military requirements. When the British offensive then began, Addis Ababa quickly disappeared from the Italian media.

Among those prisoners of war in Africa who did not want to cooperate with the Allied forces after the change of fronts were Alberto Burri, Giuseppe Berto, and Gaetano Tumiati. In 1943 they arrived at Camp Hereford in Texas, where they discovered their artistic identities. In Deaf Smith County, they also learned of the death of the Duce and two days later that of the German Führer. Officer Tumiato bitterly disapproved of the about-face that had taken place, accusing the Italians of opportunism.9 Burri began to paint; he hung onto his Sahara shirt for the rest of his life. Berto, who was awarded several medals for bravery as a soldier in Ethiopia, discovered Steinbeck and Hemingway and realized his long suppressed desire to write. In the short story Economia di candele, he describes the rape of an Oromo girl by a soldier. The theme also haunted Ennio Flaiano’s novel Tempo di ucccidere.

For the collective memory, however, another rape scene became more important. It occurs in Alberto Moravia’s war novel La ciociara about survival on the home front in the region around Montecassino, which he began in 1944 and completed thirteen years later. Vittorio De Sica, one of the most celebrated film actors of the Mussolini era, turned the book into a film in 1960 with a young Sophia Loren in the role of Cesira on her escape from Rome. The film won a Golden Palm at Cannes and earned its star an Academy Award. Through routine gags, De Sica’s melodrama proclaimed the postwar historical consensus to be neorealist cinematic folklore. The Nazi officer, speaking to the avvocato, says of the poor farmers, “They live like the Negroes.” He replies that no one forced them to do so. The rapists, looting goumiers in the French army, are “Africans” or “Turks.” In the countryside, mother and daughter take off their shoes, balance suitcases on their heads and remind us that Italian Orientalists did not have to travel far.

At the end of the 1980s, when the Cold War came to a close, Silvio Berlusconi Communications presented a television remake of the film shot by Dino Risi. This time it was in color, but still featured Sophia Loren in the main role. It is a ghostly meeting of zombies. Once again, Cesira heaves her belongings onto her head to wander together with her daughter through the theme park of Italian history.

Another historical event was the marathon at the Summer Olympics in Rome on September 10, 1960. The race was postponed to the late afternoon because of the heat, and when darkness fell, Italian soldiers lined the course with torches. The starting point was at the Campidoglio; the course proceeded past the Caracalla thermal baths, further south to Viale Cristoforo Colombo, through the EUR neighborhood to the Raccordo Anulare to Via Appia Antica and from there back to the center, finishing at the Arch of Constantine. Abebe Bikila, a bodyguard in the service of Emperor Haile Selassie, running barefoot, took the lead. One and a half kilometers before the end the runners passed by the obelisk stolen by the Italians from the holy city of Axum. Bikila won Ethopia’s first gold medal.

In February of the following year he returned to Rome for the premiere of the film La grande Olimpiade. He told reporters that he now owned a car, and he posed with Gina Lollobrigida, who had recently played the role of Queen of Sheba. La grande Olimpiade was a propaganda film for a new Italy: Riefenstahl for Italophiles. The director, Romolo Marcellini, had worked as an assistant for Carmine Gallone on Scipione l’africano in 1937 and in the same year shot the feature film Sentinelle di bronzo in Ethiopia and Somalia. He was also author of the 1936 essay “I nostri negri,” in which he euphorically described, with a view to competition from Hollywood, the “new, exclusive, and unconventional black product” from East Africa that he and his peers wanted to launch on the market.10

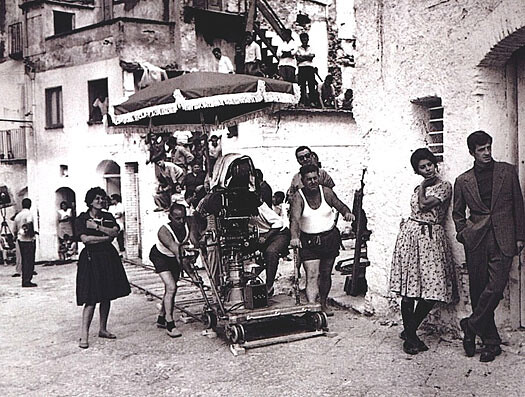

For an entire generation of Italians raised during Fascism, the proclamation of victory in Ethiopia became the high point of their lives. It was like great cinema. But in Mussolini’s empire, too, Africa could ultimately be controlled only as a cinematic fantasy. Two-thirds of Ethiopia withdrew from colonial control because the country was too large. Ethiopian guerilla units, such as the Black Lions, continued to fight the Italian occupiers and the Balkanization of their country. Mussolini’s dictum about cinema being the regime’s strongest weapon was based on Lenin’s maxim about electrification. The Istituto Luce was founded in 1924 to enforce the production of documentaries; the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia emerged in 1935, Cinecittà two years later.11 Within three years, fifty-five cinemas with 60,000 seats were built in Africa Orientale Italiana. One of the largest was the Cinema Impero in Asmara on Viale Mussolini, today Godena Harnet (“Street of Liberty”). Strict racial segregation reigned and different programs were offered: for the African audience, mainly documentaries intended as reminders of Rome’s greatness and the power of the Duce. Outside the cities, the cinema was underway via truck as a mobile unit.

After the loss of the colonies, Africa could again be located in the motherland. Everything south of Rome was Africa. Following Italy’s unification, the capitalist north saw the Mezzogiorno as a land of barbarians. One of King Vittorio Emanuele II’s generals stated clearly, “This is Africa!”12 Italy’s first colonial war used the scorched earth strategy with which Piemontese politicians and generals had suppressed the popular revolt in the south after 1861. Brigands became emigrants. In Gramsci’s reflections, the plundered south was evidence of the failure of Italy’s capitalism. But this capitalism also overcame its failure and was transfigured into national epos. Post-1945, the south delivered cheap labor to enable the economic miracle of the industry in the north. As a symbol of national unity and solidarity, the Autostrada del Sole was built. Rather than settling their African colonies, as the Fascist dream had foreseen, Italians had to search for their happiness elsewhere.

What image does decolonization leave behind when it is slept through? Do the images then become two or three times as symbolic, like the blackface scene in Antonioni’s L’eclisse (1962)? But can history really be bewitched by a gaze, a gesture? In Pasolini’s Appunti per un’Orestiade africana (1970), the director screens his 16-millimeter sketches of the planned Oresteia by Aischylos, filmed in Uganda and Tanzania, for a group of African students—all men and all without a name—at La Sapienza university in Rome. One of the young men explains to the leather-jacket-clad director that Africa is not a nation, but a continent. He is a student from Ethiopia. Pasolini’s experiments with third-world allegories were far removed from the exploitation spectacle Africa Addio (1966) by the “Mondo Cane” duo Jacopetti and Prosperi, but his sketches make evident that the postcolonial camera needs a site of belonging.

From the artificial emptiness of the EUR periphery in which L’eclisse is located, it is roughly twenty kilometers on the Via Appia to Lago di Nemi in the Alban Hills southeast of Rome. In antiquity, here was the shrine of the goddess Diana with an oak tree consecrated to her, guarded by a king-priest. Should an escaped slave succeed in breaking a golden branch from the oak and killing the guard in combat, he would become the new rex nemorensis. Every king-priest had thus murdered his predecessor. “The site once seen can never be forgotten,” wrote classical scholar and anthropologist James Frazer at the end of the nineteenth century in his cult book The Golden Bough.13

In Lo specchio di Diana (1996), Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi recall the genealogy of imperial fantasies. On October 20, 1927, Mussolini gives the order to drain Lake Nemi to salvage the remains of two magnificent ships from Emperor Caligula, reviver of the Diana myth. The following year the first ship is freed from the mud, some time later the second. April 21, 1940: Mussolini returns to open the museum in which the two ships are exhibited. One is also able to see the triumphant Duce in Tripoli in 1926 and poison-gas victims in Ethiopia. In the spring of 1944, the ships and the museum are destroyed by a fire during the German retreat. As in all of their found-footage works since the Comerio appropriation Dal polo all’equatore, Gianikian and Ricci Lucchi use historical archive material, deconstructing, coloring, and re-mounting it in a process of cinematic contemplation. Their politics of memory focuses on the problem of viewing and complicity.

Forms can seduce and be seduced. Every detail in Terragni’s style icon, the Casa del Fascio in Como, is saturated with political symbolism. The archeology of modernity believes that with a formalistic analysis, Fascism will disappear. A politics of memory assumes that there were never democratic forms. More than fifteen years passed following Pasolini’s pathetic appeal to UNESCO before the old city of Sana’a in Yemen, where he filmed scenes for Decameron in the autumn of 1970, was declared a world cultural heritage site. For several years now, on the list of candidates is “Africa’s secret modernist city” on the other side of the Red Sea.14 What is meant is Fascist modernism in Asmara. As the logistics hub and deployment area for the war against Ethiopia, the city experienced rapid population growth and a construction boom in 1935. Plans by Vittorio Cafiero and Guido Ferrazza (his was titled “Divina geometria”) formed the basis for an urban architecture that was recently placed before Miami Beach, Tel Aviv, and Napier in archeologists’ rankings for the 1930s.

Eritrea and Ethiopia are counted among the world’s poorest countries. When their governments are not battling one another in a war, then for the major powers they stage proxy wars in neighboring Somalia, which ceased to be a state almost twenty years ago. During this time Somali sovereign waters have been fished empty by international fleets and transformed into a garbage dump. In the north of Ethiopia, not far from the border with Eritrea, is the Shimelba refugee camp, which looks like a small city. “Little Asmara” is what the residents call the few streets where they have set up their cafés, hair salons, restaurants, and cinemas.

Located fifty-five kilometers from the port city Massawa, Dahlak Kebir is the largest island in the Dahlak archipelago. Only a few of the altogether 209 islands are inhabited. On the southern coast is a necropolis with thousands of graves that can be dated back to the year 912 and whose inscriptions are in Kufic. In the seventh century, the Dahlak islands, which were probably already known by the Romans, became an outpost of the Islamic world. They were under Byzantine and Ottoman rule; in between, they formed their own sultanate. The barren, flat islands, on which temperatures of 50 degrees Celsius are no rarity, were important trade centers between Eastern Africa and the Arabian peninsula. Their inhabitants were well-known as pearl divers. From here, African slaves were sent onward to Arab countries. Yemeni historian Umarā, who was executed in 1174, reported that for the Arabs of Tihāmah, black skin was common among both the slaves and the free citizens, as the men had children with their black concubines. Israel is thought to have run a military base here since the mid-1990s, and to be storing its nuclear waste on the island.

Shortly before Eritrea officially became an Italian colony in 1890, the Italians set up a penitentiary on the neighboring island Nokra.15 During Fascist rule, numerous resistance fighters from Ethiopia were incarcerated there. In the 1970s, the Derg government, together with its Soviet allies, maintained a military base on the island. Towards the end of the thirty-year war of independence, before leaving the island, the Ethiopians scuttled their ships and the dry dock with the cranes. Several of the Eritrean freedom fighters were later active in the tourist business as divers. The underwater world is rich in unspoiled coral reefs and rare, endemic species of fish. Lying on the ocean floor in the Dahlak bay is also the wreck of the Urania, an Italian cargo vessel.

How political is biological life? With his caravan traveling from Tadjourah to Entoto, Rimbaud once delivered two thousand weapons to King Menelik II. From the Red Sea, the caravan traveled past the lunar landscape of Lac Assal, Africa’s lowest point, then further through the sand desert and ultimately uphill to the Abyssinian highlands. In 1974, a more than three-million-year-old hominid skeleton was discovered along this east-west route. U.S. scientists dubbed the skeleton “Lucy.” In Amharic it is called Dinkenesh, “the wonderful.”

The demystified world and the permanent crisis of modernity have become one and the same in politicized life. It is no longer important where the lawless sites are, or what they are called. From Lampedusa to Bari to Milan, the Centri di Identificazione ed Espulsione (CIE) correspond—beyond the mare nostrum—with the Libyan internment camps in Misrātah, Sabah, and Kufrah, which are co-financed by the Italians and the European Union. Preservationists and archeologists pay them no heed. Refugees have replaced the old caravans, but the desert remains the same. Whatever direction one looks, there are only building blocks of forgetting.

See Angelo Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente? (Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 2008), 206.

Khaled Mahmoud, “My Father the Lion of the Desert: A Talk with Mohamed Omar al Mukhtar,” Asharq Alawsat, June 18, 2009.

Paulos Milkias, “The Battle of Adwa: The Historic Victory of Ethiopia over European Colonialism,” in The Battle of Adwa, eds. Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia (New York: Algora, 2005), 65. The best depiction is Haile Gerima’s film Adwa: An African Victory (1999).

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Petrolio (Turin: Einaudi, 1992), 262.

See the chapter “Selling the Black Body: Advertising and the African Campaign,” in Karen Pinkus, Bodily Regimes: Italian Advertising under Fascism (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 22–81.

Cited from Cecilia Boggio, “Black Shirts/Black Skins,” in A Place in the Sun: Africa in Italian Colonial Culture from Post-Unification to the Present, ed. Patrizia Palumbo (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2003), 295.

Angelo Del Boca, Gli italiani in Africa Orientale, vol. II, La conquista dell’Impero (Rome and Bari: Laterza, 1979), 200.

Carlo Enrico Rava, “Costruire in colonia,” in Domus 109 (1937), 25. Quoted from Robin Pickering-Iazzi, “Mass-Mediated Fantasies of Feminine Conquest, 1930–1940,” in A Place in the Sun, 208.

See Sergio Luzzatto, The Body of Il Duce: Mussolini’s Corpse and the Fortunes of Italy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2005), 79.

Cited from Ruth Ben-Ghiat, “The Italian Colonial Cinema. Agendas and Audiences” in Italian Colonialism, eds. Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Mia Fuller (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 180.

On 11 May 2009 came the fusion of Cinecittà Holding and Istituto Luce to Cinecittà Luce S.p.A. The old eagle profile has also been maintained in the new logo.

Cited from Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente?, 55.

James G. Frazer, The Golden Bough (1890; London: Penguin Classics, 1998), 856.

See Edward Denison, Guan Yu Ren, and Naigzy Gebremedhin, Asmara: Africa’s Secret Modernist City (London and New York: Merrell, 2003). The traveling exhibition with the same title was first shown in the autumn of 2006 at the Deutsche Architektur Zentrum (DAZ) in Berlin.

See Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente?, 73–88.

Category

Subject

Translated from the German by Lisa Rosenblatt.