An artist once paid a critic back for lunch by handing him a viewing copy of a video work, adding that this should be more than enough—after all, the piece was worth 25,000 Euro. Both were in on the joke, of course; both knew that a DVD viewing copy of an art video is worth even less than an empty new DVD. In a way, viewing copies do not really exist—their spectral status is owed to the art world’s economy of artificial scarcity and the severe limitations it imposes on the movement of images. Aby Warburg once called Flemish tapestries—early reproductive media that disseminated compositions throughout Europe—automobile Bilderfahrzeuge.1 Later media have proven to be rather more powerful “visual vehicles” capable of being produced on a Fordist assembly line. But rather than have the work travel to the viewer—an increasing tendency throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—in the case of video or film pieces in contemporary art the viewer has to travel to the work, installed in a gallery or museum.

In contemporary art, even pieces produced in media that allow for infinite mass (re)production are executed only in small editions. In the age of YouTube and file-sharing, this economy of the rarified object becomes ever more exceptional, placing ever-greater stress on the viewing copy as a means of granting access to work beyond the “official” limited editions and outside of the exhibition context. The viewing copy is the obverse of the limited edition: as a copy given or loaned to “art world professionals” for documentation or research purposes, it can never be shown in public. The viewing copy thus widens the reach of the work of art, but confidentially and in semi-secrecy. It is precisely this eccentric status of the viewing copy within the economy of art—which itself has an equally exceptional status within contemporary capitalism—that makes it an exemplary object, a theoretical object par excellence.

That Old Thing, Aura

In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin makes a remark that effectively undermines his suggestion that the new media of photography and (especially) film will necessarily diminish the “cult value” and aura of artistic works. After all, as Benjamin admits, Hollywood’s star system creates a new, artificial aura by carefully constructing the big stars’ “personalities,” leading to a “cult of the movie star.”2 Essential for this cult was limiting the stars’ availability—the studios knew that too much exposure posed the danger of profanation. Like certain cult images that are only removed from their shrine during important festivities, the great stars were shown to the public only under carefully controlled conditions. One did not see Garbo in an endless stream of B pictures, but only in a few choice productions. Such films were first shown in the most prestigious of “first-run” theaters, only gradually trickling down to other cinemas. Whereas Hollywood created scarcity and aura within a medium of mass reproduction largely through crafting the star’s persona and maintaining his/her distance from the audience, the art world has developed a different way of imparting aura to film and video.

Hollywood and its minor equivalents in other countries sought to control the film medium’s capacity for reproduction. Reproduction was good insofar as it benefited the system; it had to be handled with care, and the erosion of aura had to be carefully regulated. This control has become extremely difficult, as the hysterical tone of some anti-piracy campaigns and various high-profile law cases show all too clearly. The prestige of major new productions creates a desire for access that can be easily satisfied by contemporary technology. In an age in which small digital cameras allow for new films to be “rephotographed” in movie theaters in order to be distributed on cheap DVDs or online, it is hard to keep the migration of moving images—their physical movement—under control. In art, viewing copies too get recopied or kept against the “agreement” imposed by the gallery. Curators, critics, and historians (and artists) assemble entire libraries of viewing copies that perform a function similar to that of a DVD collection of feature films. However, the status of these viewing copies is quite different, as their legitimacy in relation to the “official” gallery pieces remains dubious.

Boris Groys has argued that “the video installation secularizes the conditions under which films are screened by giving the viewer the possibility to move freely within the space where the film is being shown, and to leave this space or return to it whenever he wishes.”3 While there are also other modes of presentation in contemporary film and video art, modeled more closely on those of cinema, such a secularizing impulse could indeed be ascribed to certain film and video installations. But this is far from unique to the art world, since the rise of video and especially of DVD technology has made it easy for consumers to watch and manipulate films, and made the films accessible to new kinds of analysis. Film had always been the medium of screen memories par excellence, being never present, always just past, becoming in instant memory. And to remember a film is to misremember it; viewers habitually change endings, invent or “correct” dialogue, and imagine scenes that are missing. The arrival of video changed this to a certain extent by offering possibilities for easy re-viewing and for freezing frames, giving the evasive moving image an unprecedented presence. From the geek movies of a former video store clerk to Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma, video transformed the cinema. To some extent, mythical memories have given way to more precise analysis, all the more so with the replacement of the videotape by the DVD, which has made moving images even more mobile, malleable, and accessible.

Now easily slowed down or frozen (and captured), the temporality of the moving image has become more flexible, its rhythms subject to interventions by the user—allowing an unprecedented insight into the film’s structure and texture, its overall architecture, and its “optical unconscious.” And, of course, this technology enables artists to reprocess, to dis- and reassemble, to make new works from old films—even if it is sometimes hard to suppress the feeling that the resultant works may be no more interesting than the hidden copyright negotiations. That such works are usually still presented as exclusive limited editions could be seen as a predictable outcome of a reactionary aesthetical/political economy that uses artificial scarcity as a means of producing value. Contra Groys, one could therefore argue that the film/video installation represents a throwback when compared with the wider video/DVD culture, since video installations exist in limited editions, as do most single-channel works. Regardless of the mode of presentation, the art world re-auratizes film and video by limiting the number of copies.

Many artists proffer a seemingly legitimate reason for being anxious about viewing copies: their works are supposed to be seen under very specific conditions in a gallery space. While this desire for “proper” installation complies with the art world’s mystificatory economy of exclusivity, which still uses as its ultimate model the unique cult image in its sacred precinct, it is of course understandable that artists would want their work to be seen under the right conditions. However, it is a mistake to think that these must be the only conditions under which a work can ever be seen. In an age in which everyone is used to seeing moving images in incredibly degraded forms online, viewers have a great capacity for “correcting” these conditions in their mind, for imagining the “proper” presentation. Seeing shaky illegal copy of the latest blockbuster on a laptop does not really damage the film; if anything, knowing that it must be so much better when seen under optimal conditions can only increase its aura.

The dialectic of de- and re-auratization is thus rather more complex than Benjamin allowed. As tempting as it may be to try to match the fervor with which he posited “right” and “wrong” ways of dealing with film—allowing it to unfold or curtailing its ontological promise, respectively—there is no reason to assume that the near future will bring us anything other than a hybrid culture in which cult value and exhibition value develop in an increasingly complex interplay. A culture, in other words, that resembles the present, but not without a little difference that is worth fighting for: an emancipation of the viewing copy, resulting in a different distribution circuit alongside that of limited editions. In such an economy, the availability of works would be less dependent on personal connections and clout, and while one should not have exaggerated expectations of art becoming “popular,” let alone—Benjamin-style—of the public’s reception becoming more “progressive,” such a development would certainly increase access to certain pieces for those who are interested, which cannot be a bad thing.

Ultimately, one suspects that the emergence of over-the-counter viewing copy editions was halted not so much by fears that the “real” work would be tainted artistically and/or financially, but by the fact that there was big money to be made from exclusive limited editions. Even if unlimited viewing copy editions do not threaten the aura of such gallery pieces, why bother with them when the returns are bound to be marginal at best, or, more likely, non-existent? High-profile works such as Fischli and Weiss’ Der Lauf der Dinge, Johan Grimonprez’ Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, and Mike Kelley’s Day Is Done have all been released on DVD alongside their existence as gallery pieces, but not every work is a Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y. However, file-sharing sites such as Karagarga show that there is a real interest, albeit among a select group, in viewing copies—now dematerialized—of artist videos and various other forms of underground or avant-garde filmmaking. Such not-so-legal file-sharing should be seen as an incentive for the art world to explore forms of production and distribution that demand little in terms of investment. From burn-on-demand to making films available online, an “official” circuit could both coexist with and profit from the illegal one.4

The Time of Our Lives

Even if they are still hesitant to take such steps where their own (especially, new) works are concerned, some artists are nonetheless beginning to experiment with alternate viewing conditions, sometimes reexamining old and decaying formats in the process. With his installation Pretty much every film and video work from about 1992 until now. To be seen on monitors, some with headphones, others run silently, and all simultaneously, Douglas Gordon has effectively made a viewing room for viewing copies of his own work. While his works are almost always projected, his films and videos are here shown on monitors, under conditions that differ sharply from their installation requirements as gallery pieces. Even while Gordon here retransforms viewing copies into a gallery installation, this installation nonetheless celebrates the power of images to survive (and indeed thrive on) decontextualization and degradation, and it can be read as an invitation to rethink the status of gallery works by way of the viewing copy that allows the combination and recombination of images.

In his Video Palace installations, Joep van Liefland glorifies the lost world of VHS video stores, in particular the non-franchised and seedier ones. While Van Liefland usually also mounts or projects posters for his own short low-budget exploitation flicks, the installations are dominated by ramshackle racks on which the artist lovingly exhibits the ephemera of an already bygone culture: cases of cheap exploitation videos in a variety of genres. Having become obsolete as a medium for moving images, the tapes are occasionally used as purely material building blocks. One could imagine an experimental “high art” version of Van Liefland’s Video Palace with video art tapes from the late ‘60s to the early ‘90s. As a repository of trashy mass culture whose capacity to produce aura is dodgy at best, Video Palace might be one way of returning to earlier distribution models that differ from today’s culture of exclusive editions, many of which were proposed in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. As the material disintegrates, the relics of videotape could stimulate a rethinking of current modes of distribution, and to once more make videos more widely available, over the counter, and sold at affordable prices.

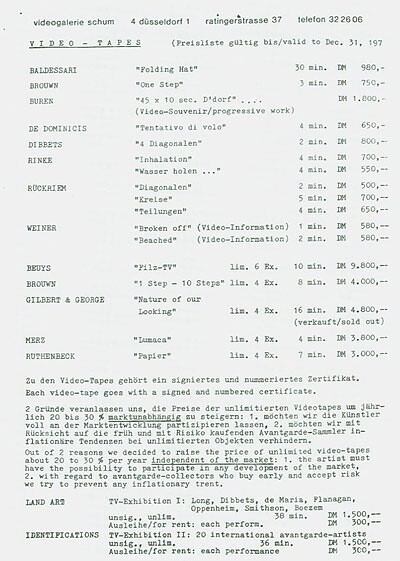

Recent years have seen exhibitions and publications on some of the relevant activities and organizations from that time, such as the Videogalerie Schum, but a fundamental reflection on the implications of such initiatives in light of current concerns has barely begun.5 The economical difficulties experienced by initiatives such as Schum’s are as instructive as Godard’s protracted attempts to finance his Histoire(s) du Cinéma. At one point (when the project was still called Histoire(s) du Cinéma et de la Télévision) Godard proposed to release the film as a series of one-hour-long video cassettes that would cost between $60 and $100 to produce and sell for between $250 and $500 per tape—thus clearly aiming at institutions rather than individual consumers.6 Schum’s even heftier prices, even for unlimited editions, effectively also limitited the tapes’ availability to institutions and “serious” collectors. That home video equipment was not yet in wide use at the time of the Videogalerie Schum, or even at the time of Godard’s proposal, obviously limits the lessons that can be drawn from the respective business models, yet these initiatives remain important for having sought a third way beyond both mainstream film distribution / network television and the creation of aura through extremely small editions. Less canonical initiatives such as the 1990s’ Amsterdam-based Zapp Magazine—a magazine on VHS tape that included artist’s videos as well as reportage—have been at least as relevant as veteran institutions such as Electronic Arts Intermix and more recent initiatives such as e-flux video rental.7

If galleries, publishers, and other organizations were to start official “viewing copy editions,” there might be a real impact on the ways in which film and video art are seen—and made. Hybrid forms are imaginable and likely: a coexistence of “exhibition copies” intended for installation/projection and viewing copies meant for computer or TV screen. In fact, this is already happening. A work such as Renzo Martens’ Episode 3: Enjoy Poverty (2009) is or will be screened at film festivals, shown and sold as a video installation, broadcast on TV, and distributed in the form of a DVD. As with feature film, the timing of the release is crucial; the DVD arrives well after the film’s premiere at film festivals and in art spaces. We thus―finally―seem to be moving towards a culture of officially sanctioned viewing copies, although its conditions are still imposed on the viewers and are subject to economic rationality.

At best, such general DVD releases could provide opportunities for reshuffling a piece’s elements, for producing different but equal versions. While some aspects of a work may not translate so well into viewing copy conditions—especially in the case of multi-channel installations—these conditions can also allow one to better decipher the piece than one would in actual gallery conditions. A model here might be Michael Snow’s reworking of his seminal 1967 film Wavelength into the DVD WVLNT, or Wavelength for those who don’t have the time (2003), which consists of three superimposed 15-minute segments from the original 45-minute film. Snow’s ironic subtitle points to changes in the temporal fabric that are not just a simple matter of people having “less time”; indeed, the sense of not having enough time is itself an effect of the post-Fordist erosion of the boundaries between work and leisure. If, as Antonio Negri has argued, industrialism tended to reduce all labor to a merely quantitative, measured time, to a state in which “complexity is reduced to articulation, ontological time to discrete and manoeuvrable time,” the times have been a-changing for quite a while now.8 In the “social factory,” the whole of life tends toward becoming labor, which, according to Negri, has radical implications:

Time itself becomes substance, to the point that time becomes the fabric of the whole of being, because all of being is implicated in the web of the relations of production: being is equal to product of labour: temporal being. … At the level at which the institutional development of the capitalist system invests the whole of life, time is not the measure of life, but life itself.9

Of course older, industrial (and pre-industrial) rhythms evidently continue to exist, even if they are also subject to change, as with the rise of “just-in-time” production. And even for those at the forefront of immaterial labor, things are not clear-cut; as Negri himself argues, capitalism once more tries to reduce complexity to articulation, lived time to measured time—on a larger scale and more completely than before. This suggests that one should not think of time-as-measure being replaced by the time-of-life; rather, the two produce an ever more complex dialectic, as measure morphs and becomes more flexible, and as “ontological” lived time is hardly ever completely disconnected from forms of measurement that seem be subject to topological distortions. Is the viewing copy, which can be seen under varying circumstances—stopped and fast-forwarded at will—not the perfect embodiment of this complex, aggregate temporal economy?

This is, to be sure, the potential limit of forms of art that distinguish themselves as being perfectly “in step with the times,” as viewing copies do just as much as spectacular video installations. As events, the latter however function as an essential part of the “social factory” in which work is play and vice versa, in which the production of subjectivity produces workers who sell much more than just the abstract labor-power on which industrial capitalism founded its logic. That video installations and viewing copies alike are de leur temps is neither to be applauded nor to be deplored. If Snow’s Wavelength, with its single 45-minute zoom and its hypnotic soundtrack, seemed to celebrate film’s power to create durations beyond measure, the WVLTN re-edit complements the original film by showing the resurgence of measure, thus using the viewing copy format for more than mere reproduction. The viewing copy’s exemplary status in the current temporal economy is merely a precondition for artworks that may either exploit it in facile ways or follow the example of Snow’s WVLNT by using the form to make tangible the complexities and contradictions of today’s moving images.

Aby Warburg, “Mnemosyne. Einleitung” (1929), in Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, ed. Martin Warnke and Claudia Brink (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2000), 5.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 231.

Boris Groys, “On the Aesthetics of Video Installations,” in Stan Douglas: le Détroit (Basel: Kunsthalle Basel, 2001), unpaginated.

This would of course have to entail a rejection of corporate copyright fundamentalism, which led to the lawsuit against The Pirate Bay. But regardless of whether one is an “intellectual property” hardliner or an advocate of Copyleft, it would be folly not to offer one’s moving images via an official channel as well.

For Schum’s initiatives, see the catalog Ready to Shoot: Fernsehgalerie Gerry Schum, videogalerie schum, ed. Ulrike Groos, Barbara Hess, and Ursula Wevers, (Düsseldorf: Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 2003).

Jean-Luc Godard, undated proposal for Histoire(s) du Cinéma et de la Télévision, in Jean Luc Godard, Documents, ed. Nicole Brenez et al. (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2006), 281.

While organizations such as EAI are important, their prices are forbidding and even shocking to those who are accustomed to “normal” DVDs. In this respect e-flux video rental is an interesting alternative, though the emphasis on the selection of the materials by a variety of curators also suggests that this model is still firmly rooted in an art-world economy in which access to moving images is highly regulated and mediated.

Antonio Negri, “The Constitution of Time” (1981), in Time for Revolution, trans. Matteo Mandarini (New York/London: Continuum, 2003), 49.

Negri, “The Constitution of Time”, 34–35.

Category

Subject

This text will be the point of departure for a presentation at the James Gallery in the CUNY Graduate Center, New York, as the final part of a three-part exhibition to be curated by the author during the first half of 2010.