Positions June 2009

Making art, as I’ve always put it, is a habit—a poor one in my case. Making art is not initially creation but constant repetition, salvaged by making puny differences in certain orders on the plane of the feasible. Art is, semiotically speaking, purely negative; it cannot be defined positively. And of course doing it entails not doing something else. Like some of my Iranian colleagues, I’m not doing it these days. We have all seen frames that we can freeze, stick to, and damn. Barring whatever may cross the thresholds of our studios and whatever may enframe and transcend what has been going on in the streets of Iran, perhaps the same thing crossed each of our minds: we have no future.

Certainly we are also established abroad and we can have our own futures beyond these walls, but I’m speaking of those like me who have refused to leave the country and who have decided not to become one more seated in Matisse’s easy chair, chanting “I will rebuild you my country with these tears,” or one more dissolved in the out-of-context souks of the UAE. We have chosen to breathe hatred, tear and pepper gas, instead of hanging onto nostalgia and the myths of exile and of “the innocent artist.” So it’s true to say that in the eclipse of relative political freedom and under the oligarchy and inquisitions of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, we—like millions of Iranian citizens—have planned our to-be by abandoning “labor” and “work” in favor of “action.”

With these words, I would also like to dedicate this paper to all my compatriots and—for the reasons discussed in this paper (and not to be auctioned in October at Christie’s), and because in a situation where even e-flux is sending a petition to the UNO and the EU, Magic of Persia is still financially thinking pink—I declare that as one of the seven finalists for the Magic of Persia Art Prize (MopCap) I strongly denounce their criteria and withdraw my works, for as they would have it:

The contemporary Iranian art scene is not to be underestimated. Recent auction results stand as testament to the global acknowledgement of the vitality of Iranian art, with artists such as Shirazeh Houshiary, Shirin Neshat, Parviz Tanavoli and Farhad Moshiri commanding record prices at sales around the world.1

***

The E Word

I assume that today we are all familiar with the terms “exotic” and “exoticism.” We usually take them to be successors to nineteenth-century Orientalism, but exoticism today is much more complex than Ingres’ or Renoir’s Odalisques. There are those in my circle who have condemned many artists by labeling them “exotic.” And my colleagues and I have been swearing at each other using the E word. I do not agree that being exotic proceeds from some sort of defect, for you may use local motifs in your work, and that may appear exotic to tourists or those curators who come mining. Hence exoticism has little to do with being exotic; it is rather a trend that operates within an ideological apparatus.

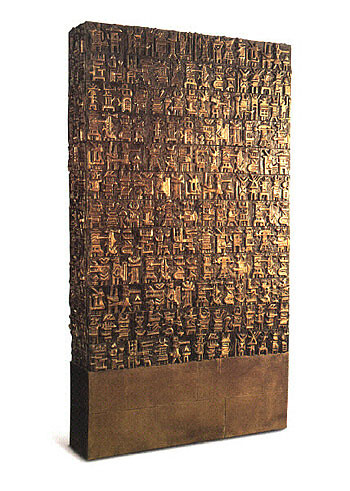

I have participated in several events and contributed to publications devoted to so-called contemporary Iranian art, the Tehran contemporary art scene, or new art from the Middle East. Today every schoolchild knows that the recent increase in interest in the region stems from the catastrophic geopolitical state of affairs in my country and in those of its neighbors, and also from the brand new art market in the United Arab Emirates. Bonhams Dubai, for instance, reportedly broke thirty-three world records at their $13 million Inaugural Middle East Auction. That was almost three times the expected result, with a phenomenal 94% of lots sold.2 I’m not saying Orientalism is no longer a force; on the contrary, today the market is much more hungry for exotic commodities and, at least in Iran, one of the leading trends in art is decorative calligraphy and a modernist approach to patriarchal heritage. Parviz Tanavoli’s Oh Persepolis, which sold at Christie’s Dubai for $2,841,000,3 is an example of this trend. His works, like what was being sold at Saatchi’s gift shop during its recent “Unveiled” Exhibition (such as “mouse rugs”), are exotic rather than exoticist.

Maliha Al Tabari, the managing director of ArtSpace Middle East Gallery, admits that “typically, the people who buy from us are the kind that can definitely afford it … mostly they are people in the banking industry.” She continues, “I’ve been in Dubai for six years and I came when there was almost no art … We were trying hard to sell pieces by Farhad Moshiri for about $2,000 (Dh7,500) or $3,000 (Dh11,000)—now his work is worth $200,000 (Dh740,000) or $300,000 (Dh1.1 million).4”

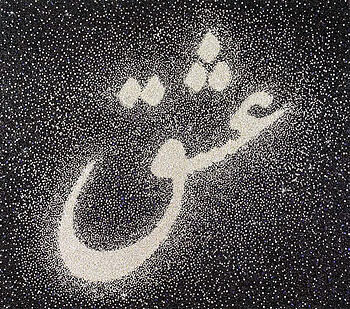

Today Farhad Moshiri is the most in-demand Iranian artist on the market. His Eshgh (love) was auctioned by Bonhams and sold for over $1 million.

Middle East: The Floating Signifier

The use of the term “Middle East” does not date back to prehistory, and it has little to do with the Achaemenid Persian Empire, Babylon, or the Herat School of Painting.

Like “Eastern European Countries,” the Middle East does not exist geographically. “West” and “East” too are not merely geographical terms; the Orient, for instance, has odd connotations—“oriental martial arts” never refers to Turkish or Iranian traditional martial arts, for example, and the case is the same for “oriental massage.” And in pornography “Asian teens” are neither Lebanese, nor Iranian, nor indeed Afghan.

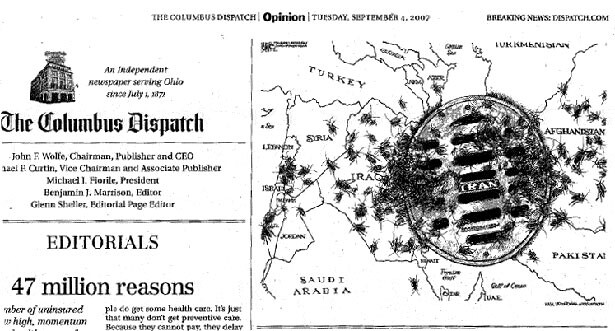

The region was constructed in the nineteenth century, the term coined in the British India Office, the department responsible for administering the Indian subcontinent during the British Reign (Raj, 1757–1947), and later popularized by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan. Mahan chose this geographical term for the areas surrounding the Persian Gulf—what Gamal Abdel Nasser later called the Arabian Gulf: both sides are still vying for control of the name. Mahan believed that, after the Suez Canal, the Gulf was the most strategic route for any British attempt to stop the Russians from advancing towards India.

The Middle East does not exist geographically not just because it’s constructed and still seen from a Eurocentric viewpoint—for a Chinese person it is located to the west, for a Russian to the south—but also because we cannot define its borders and areas, that is to say, we cannot designate a unified object. UN analysts often use relatively more descriptive terms such as “Near East.” They also refer to it using the term “Western Asia,” but on the UN’s official website Iran is not a part of Western Asia but rather Southern Asia. This is not what Mahan desired: “Western Asia” now includes Armenia and Azerbaijan, both once Russian. The United States government first used the term “Middle East” when in their eyes an opposing force was growing in the region, namely, Communism (or “Atheism,” as Eisenhower put it). As the region is the site of a large percentage of the world’s oil production, the Eisenhower Administration saw the growth of Communism in the region as a serious threat towards the U.S. and its spiritual or anti-communist allies’ “economic life and political prospects.” Let us cite his “Special Message to the Congress on the Situation in the Middle East”:

It would be intolerable if the holy places of the Middle East should be subjected to a rule that glorifies atheistic materialism.5

In his speech Eisenhower is really concerned with three major, interconnected matters: oil, independence, and spirituality. These three matters and “non-matters” meet again in Ahmadinejad and in Iranian spiritual and official artists.

What is this restless attempt to maintain consistency for the Middle East, since—to borrow Lévi-Strauss’ term—it is but a “floating signifier”?6 In 2004 the Bush Administration coined the terms “Greater Middle East,” “New Middle East,” and “Broader Middle East.” According to U.S. administration preparatory work for the thirtieth G8 summit, this wider region includes “the Arab states, Israel, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Some pundits go further and include all of Central Asia or the Caucasus.”7 Perhaps one day museums and galleries will start vying for exhibitions devoted to what the Bush Administration sought to encompass.

Why do we need to keep the Name, even though its referent has been changing geographically ever since the day of its baptism; even though it does not signify a cluster of descriptive features and subsequently does not refer to an object in reality or at minimum a geographically, politically, socioculturally, and economically circumscribed region—in brief, a “sense” that does not possess an extension of descriptive “references”? The name has not designated the same object and the word has been transmitted from subject to subject while the object has been changing. Over time the signifier has been preserved. If we try to fill the void today with positive cultural or geographical realities, we are—again—designating an empty signifier in a “retroactive” manner, that is to say, we constitute the name after we’re in it—after politics has already shaped the name.

Most of the exhibitions, panels, and conferences that we find more radical than the import/export art scene of Dubai, its related auctions and numerous art fairs, are those whose curators and organizers have begun by opposing the “mainstream,” so-called “Western media representation.” All these programmes speak of cutting-edge works of art produced “in the region.” The common achievement of all these discourses—those that try to constitute political, cultural or geographical “identity” for the baptized object beyond its ever-changing descriptions—is: there really is a Middle East; that the Middle East is for real. They all try to designate what—in their eyes—has always been there. This is the omnipresent characteristic of all those efforts that operate retroactively.

“Arab” as the One

So what is keeping this borderless region or, should I say, this void, full or consistent, if full or consistent is what it is? For this we should examine the common experience of its given reality which, like any other historic reality, achieves its identity and unity through the mediation of a signifier that can symbolize our experience of its meaning. When, from time to time, institutions, museums, galleries and their curators, while trying to fill this void, to locate and determine “the region,” make grave mistakes, they are actually symbolizing diverse geopolitical and sociocultural experiences. Saatchi’s newsletter for the “Unveiled” exhibition is a good example:

On 30 January the Saatchi Gallery’s second show, Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East, will open, presenting the work of over 20 of the region’s most exciting artists. Dedicated to the flourishing contemporary Arabic art scene, the exhibition will offer a cutting edge survey of recent painting, sculpture and installation.8

And in the exhibition’s picture by picture guide, concerning Rokni Haerizadeh’s Dagger Dance, it is written:

Dancing with swords is a traditional custom throughout the Arab world, usually performed by women as part of a wedding ceremony. Haerizadeh delivers this scene with the vivid exoticism of Matisse or Gauguin, his bold colours, heavy outlines, and opulent patterning re-appropriating the tradition of “orientalism.”9

Why is the catalogue also in Arabic? Where does “the flourishing contemporary Arabic art scene” come from when eleven of the twenty-one artists are Iranians? Perhaps one has to be a Panofskian iconologist to tell the differences between Yemeni, Turkmen, and Qajar courtier dagger dancers, but Haerizadeh has in any event had recourse to a very illustrious hypotext, known to anyone who has skimmed through a concise history of Persian painting (see below). It’s true to say that these are neither blunders nor a matter of opinion; they derive, rather, from certain varieties of doxa. “Arab” is there to cut the chain of signifiers, and thus serve as the ultimate point of reference. It operates effectively when we say—like Tom Cruise when he spoke about the policy of Scientology—“this is it, this is exactly it.”

When the holders of such discourses—those who designate the region as the “Middle East” by abandoning dissimilar qualities, homogenizing and producing a unified entity such as “Arabic”—hand on to us certain signifiers as “the Signified,” they in fact nourish certain systems of belief and ideological maxims. The main achievement of all these unavoidable gaffes, unbeknownst to their agents, is that it is the imaginary other that calls for “thereness” and seeks objectivity, be it paradoxical, undemocratic, or simply bullshit. It’s the same with our politicians: the leaders have been speaking of “the Enemy” ever since the revolution, and the slogan has been “neither East, nor West, the Islamic Republic [only].” But every day when we were at school we had to trample something underfoot, even if it was just an Israeli or American flag painted on schoolyard pavement.

The ideological apparatus does not welcome Turkish artists so often. Although Turks are geographically represented as inhabitants of the region, they are not that Arab or that Muslim or that fanatic anymore (needless to say, today “Arab” and “Muslim,” the “Arab world” and the “Muslim world”—thanks to common sense—refer to one another and can be used interchangeably), even though the Ottoman Empire was supposed to be the center of the so-called Islamic World. We do not see very many Turkish artists in the exhibitions devoted to “the region,” for, since Atatürk, there are serious social and even military forces perceived as absolute defenders of secularism.10 Remember that Turkey is potentially an EU member and a NATO partner.

It’s not just unscholarly curatorial texts (such as Saatchi’s) that permit such homogenizations; some political analysts, in discussing “The Greater Middle East,” refer to the Arab states alone, and for the American government, in its proposal presented to that G8 summit, “Arabs’” problems are the region’s problems.11

To construct this “real” other, there is surely a need for an “us and them,” an old discourse to which I do not wish to reduce my theory; that is the very discourse of otherness in which others are simply those excluded. This discourse assumes that cultural units, social organizations, ethnicities, and races are privileged and maintained through different processes of exclusion and opposition based on a straightforward dualism.12

“Middle East” has so often been filled with another void, with an empty signifier which operates as the last signified: Arab. In an international biennial, an artist who could only read and write in French was insistent that he was just an Arab; seen wearing only his undershirt, belching throughout the biennale, his answer to each and every complaint was: Quoi? Je suis arabe!

Being an Arab has little to do with one’s genes, the degree of pigmentation, location or language; and, of course, it is not about diverse Arabic dialects and descendants; it is neither about secular Nasserism nor about Islam. The experiences of Arabité as historical meaning can only take place on an ideological plane. “Arab” does not designate a real object and has no rigid point of reference; it is itself the Referent, i.e., a knot that, when multiple signifiers are floating in discursive fields, intervenes and stops their slide. Since the “Middle East” does not exist in a geographical space but only on an ideological plane, and is more concrete than the heap of its referents, eventually it is unified and identified through the agency of a master-signifier: “Arab” is there to unify dissimilar historical realities through symbolization. The name “Arab” has been extravagantly saturated not because it is the richest word, but because it is empty. For the Name is prerequisite: we need it to accumulate our heap retroactively, a paradoxical heap of others. And, in brief, we need it to unify a mass. This does not only suggest that a social bond is there, allowing one to refer to this full-empty entity by uttering the Name, but beyond this, it reveals the reign of the commonsensical.

“Arab” appears to connote a cluster of quasi-descriptive features: Muslim, anti-Semite, stinky, outlandish, undemocratic, vigorous, rambunctious, camel-riding, bearded or veiled, a man with a long circumcised penis: in brief, the new Jew. It is certain politics, migrations, terrorist activities, and the “democracy-imposing” invasions that permit such connotations. And the reign of common sense can be perceived in a simple tautological assertion: we say they are as such because they are Arabs.13Arabité is a vacuum that gulps down certain connotations.

Here the Middle East is the world’s most stinky part, or the pain in the world’s arse, or, to borrow Mohamed Sid-Ahmed’s words, “a mainstay of world terrorism.” 14The dark side of the globe, like the anus, has its fabulous obscurities and is full of mysticism, for there should be more in it than a hole.

Today, Iran is the most strategically important country in this region; it is the alma mater of all the evils around it; it spreads cockroaches (remember how the Rwandan radio station RTLM referred to Tutsis) and embraces curators willingly.

Today it’s hard to recognize Arabs, not just because they are everywhere, but also because they’re like “us”—they no longer “go to school every day by camel.”

How does art support the quasi-tautological assertion that says “there is a Middle East because there are Arabs living there and they are Arabs because they live in the Middle East”? Saatchi’s newsletter was a simple example, but we should not overlook the fact that there are artists supporting such claims. I have distinguished a few dominant orientations in Tehran’s Art scene of today (let us not call it contemporary). Among these, the art market has chosen a certain trend: aestheticization of stereotypes. Many have said that this exoticism functions as abjection. In contrast with Catherine David, I insist that we should not call it self-abjection or self-exoticism, for although the subject of abjection, the exoticist, is an inhabitant of the altered territory, and although unanimity and hegemony have constructed a vague, abstract, and paradoxical whole (a “we”), the artist usually extracts himself/herself from this mass to enframe it from afar. This gives way to a “beautiful mind” and lets the artist be both insider and outsider. For we should not overlook the ambivalent nature of abjection—abjection is letting go of something we still keep. We recognize semen, excrement, or dismembered organs as once being parts of ourselves—they are dismembered bits of us.

All these mechanisms have something in common; they all create or—unbeknownst to their agents—support the constructed mass by attributing to it an ethnic, geographic, cultural, or political reality to homogenize diversity and difference. For instance, take Shirin Neshat’s answer to why she has hung onto “Chador art”:

In Iran, the chador is reality. That’s just the way people dress. Or at least some people.15

Or a curator’s note on Shirin Aliabadi’s Miss Hybrid series:

Shirin Aliabadi’s photographs capture the desire of today’s Iranian women to reshape their image—transforming themselves as acts of cultural rebellion.16

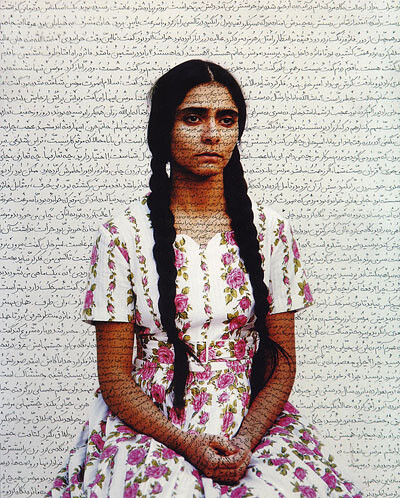

As I have said before, the altered territory is an unreal mass, it’s a façade. The aforementioned trend represents this façade. Among Iranian-born artists, the pioneer, we know, is Neshat, but today she’s important precisely because her works have aestheticized this façade to such an extreme degree. When I told her this, she claimed that there’s nothing wrong with this, for she’s an admirer of beauty and chadors make beautiful shapes. Here we deal with art’s oldest platitude, its ancient auxiliary and appurtenance: beauty. In her recent photographs—like her most famous series, “Women of Allah”—Neshat has used Persian writing.

In this piece, language has lost its function and carries the charm of the unfamiliar, and so becomes mere exotic ornament. What is there for anyone who can read Persian? Neshat has employed such an excess of superfluous and incorrect diacritics that no one is able to pronounce her words. These are no longer words but ornaments, knick-knacks, and an answer to the market’s demand for the “arabesque” and Arabic letters without knowing what they are.17 Especially in Dubai, there is a constant call for calligraphy, no matter what the text reads.18

The success of Ghazel, another Iranian artist based in Paris, lies in nourishing common sense and adopting various strands of doxa. In her videos the chador, the most inspiring cliché, embraces all dilemmas: for Iranian women, feminist activities are unlikely, because the chador will not let them climb up a standard truck step, and Iranian activists perceive feminism as lumpen illiterate people do, as tantamount to manhood. But it is Ghazel’s video which resides in an ideological field, from where she perceives feminist activism as exerting “manly qualities.” Let us remember that the feminist movement in Iran has been one of the most active movements demanding changes to discriminatory laws. According to the Barbican Cinema, she’s “reflecting on social and gender issues in Iran,”19 but the way she ridicules feminism is the same way official agents of ideology mock these demands in Iran.

Of course it’s much more difficult to analyze serious egalitarian movements in Iran than to add to common beliefs, and for Neshat too it would have been an onerous task to analyze Forough Farrokhzad’s intertextuality and search for the roots of her poetry in The Wasteland. I’m not saying that she has intentionally chosen to portray the poet as a fragile, mesmerized woman, for in The Last Word (2003) it is not just Neshat, Barbara Gladstone, or Shoja Azari “speaking”; it is the common wisdom; it is platitude that calls for delicacy and the myth of Beauty. And of course to satisfy this need for beauty one need not search in vain; samples are already there: a hammam with naked women (remember Ingres), and then we insert an anorexic naked girl taken from the “No Anorexia” poster to oppose Orientalist imagery! And it’s for the sake of beautification that, for the film Munis, she bought her cloud scene from Getty Images. It is “Everyone” that would say, “that is beautiful indeed.”

Unanimity

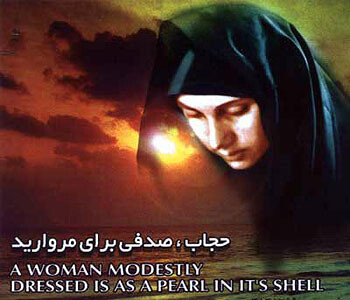

The exoticist product is an ideological parole—this is the definition of façade. An ideology maintains its consistency when it stops meaning from sliding about. Such paroles impose signifieds to pin the supposedly open-ended meaning down. Unanimity or absolute concord entails a belief in the naturalness of this signification. Surprisingly exoticists are famous for being subversive artists, but as mentioned earlier, their products are paroles of the same langue, the language of an ideological regime. The way Neshat treats the chador is the way the culture factory of the Islamic Republic beautifies its restrictions; they too aestheticize the veil in their murals, posters, and slogans. For them, a woman in a veil is like a pearl in its shell. The apparatus too is similar (compare Ghazel’s videos with posters and slogans of the regime: “The veil is serenity” is as ideological as “the veil is THE problem”).

Ghadirian’s Like Everyday Series (2001–2) is an accumulation of ideological paroles and is an exemplar of exoticism as a trend. The Like Everyday Series shows women in chador with their faces veiled by domestic appliances: one should not forget that Muslim or Iranian women are just identical housewives. And it’s important to repeat this in different photos because ideological utterances resemble moral judgments and religious prayers, for they restlessly seek unanimous approval. Her Qajar series embraces “our anachronistic life” as common wisdom does: Westoxication.20 Westoxication is not a harmless theory, today, in the Stalinist show trials of the Iranian regime, reformists have to defend themselves against westoxication as a charge.

The veil has become the easiest way for an artist to promote his/her work. Another Iranian artist has produced a film to promote her art. After she shows an archive of her different projects and works, she shows herself in high heels wearing a headscarf standing by a closet. She enters the chamber and frees her hair from the scarf and the door closes dramatically. This symbolic act has nothing to offer Iranian society, as she never performed it within the society. This was just marketing.

Shadi Ghadirian, Farhad Moshiri, Ghazel, and Shirin Ali-Abadi perpetuate the dominant image in a very direct way; no pentimenti or “curvatures” are there to be seen. They take advantage of doxa and hegemony and submit to it in the name of subversion.

Now we understand that a narrow view is not only due to naïveté; it is also what an ideological system has to offer. But the common result of this trend is not only the simplification of dilemmas, which makes people more docile and mediocre, or the aestheticization of façades, reinforcing the idea that there is a homogenous region and that the mass is for real; beyond these, the praxis of art is disturbed because refiguration is no longer a vital issue. This is again how an ideological utterance castrates thinking when pinning down meaning. When foreseeable, the “doxical” and its audience give each other standing ovations, for they understand each other; for “they know what they mean.” In certain species of doxa, ideological values, historical phenomena—which have come to function as realities—recognize themselves.

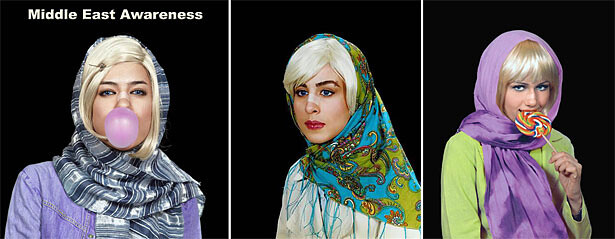

Michael Irving Jensen has chosen one of Aliabadi’s Miss Hybrid pieces for the website www.middleeastawareness.dk. The answer to the question “Why Shirin Ali-Abadi?” is the answer Dubai Tourism has given to “Why Dubai?”: “captivating contrasts.”

The media today typically uses such contrasts in representing Iran. In March 2006, Susan Loehr’s reportage on ARTE television’s “Metropolis” programme begins by showing such captivating contrasts as veiled “chicks” wearing extravagant makeup with dyed hair, standing before murals of martyrs’ portraits, or a mullah speaking on his mobile phone. Then the narrator tells us that we’re used to such representations, but today they are going to show us something different.21 Shirin Ali-Abadi not only perpetuates the pictorial representation served up by CNN or VOA22, but also follows the Islamic Republic’s discourse of “cultural invasion of the West”: that young Iranian people are having an identity crisis; that they are no longer identical with themselves; that they cannot be themselves. Since this series by Ali-Abadi—as an ideological and propagandistic commodity—is produced in order to be consumed immediately, she is not about to content herself with the mediocre pictorial representation of this ideology, and so entitles the series “Miss Hybrid.” The same can be said with regard to Shahram Entekhabi’s Islamic Vogue.

The Abyss

Among Ayatollah Khomeini’s catchwords and slogans was “unity of words” or unanimity. With this he drew a boundary between “us” and “them,” reined in diversity, and nipped pluralism in the bud in the very beginning of the Islamic Revolution.23 Unanimity is absolute concord and harmony. When unanimous, everybody is believed to be of the same mind and acting together as an undiversified whole, as an “army of 20 million,” as Khomeini had put it.

Instead of piercing holes in the overlooked, unsymbolized (or at least less symbolized) realities relating to subcategories of those ideological maxims and the commonsensical, these artists acted unanimously and transmitted their messages at the behest of a closed society, a privileged and established clan. The agents of ethnic marketing won out over dissident narratives and became part of the hegemonic discourse, not because their narratives were better able to match the “facts,” but because they were better able to fulfill the desire for predictability and were indeed much better able to answer the demands of a huge number of potential customers. And that’s what exoticism is: the representation and production of ideological commodities and symbolizing parts of a culture for consumption by those consumers who wish to reinforce their identical positive identities by way of stigmatizing others.

All of these artists are still inhaling doxa and are becoming more and more hegemonic, but in contrast with official or governmental artists, they are praised in the name of subversion. They should fight with monsters, yet it’s true that “whoever fights with monsters should see to it that he does not become one himself. And when you stare a long time into an abyss, the abyss stares back into you.”24

Magic of Persia Contemporary Art Prize, “About,” →.

Bonhams, “Bonhams Dubai Breaks Thirty-Three World Records At $13M Inaugural Middle East Auction,” no date, → (accessed August 22, 2009).

This is a record for a sculpture by an Iranian artist, a world auction record for a work of art by any Middle Eastern artist and the highest price achieved for a work of art sold at auction in Dubai. Christies, “Arab, Iranian & Turkish Art (Modern & Contemporary): Exceptional Prices,” →.

Shehab Hamad, “Dubai Art Maket’s [sic] Future,” S3AF: Middle East Art. News and Commentary, January 1, 2009, →.

The American Presidency Project, “6 - Special Message to the Congress on the Situation in the Middle East. January 5, 1957,” University of California, Santa Barbara, →.

First used in Claude Lévi-Strauss, “Introduction à l’oeuvre de Marcel Mauss,” in Sociologie et anthropologie, by Marcel Mauss, (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1950).

Völker Perthes, “America’s ‘Greater Middle East’ and Europe: Key Issues for Dialogue,” Middle East Policy Council Journal XI, no. 3 (Fall 2004).

Since I was a participant myself, I received the announcement much before the opening via email. Here ‘the flourishing contemporary art scene’ is quoted: →

‘Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East’ Picture by Picture Guide. (no further information was indicated)

Kemal Atatürk did not want to mix politics with militarism.

The London-based Arabic daily Al-Hayat obtained a copy of the proposal and published the document in its entirety on February 13, 2004; the English translation was later published by Al-Hayat on its Web site, and is available at Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, “G-8 Greater Middle East Partnership Working Paper,” →.

In this discourse we could have said that the excluded are befriended only by and through Orientalism.

Žižek believes such appearance of tautology is false because “Arab” (“Jew” in his text) in “because they are Jews” “does not connote a series of effective properties, it refers again to that unattainable X.” Slavoj Žižek, “Che Vuoi?,” in The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1999) 96–7.

Mohamed Sid-Ahmed, “On the Greater Middle East,” Al-Ahram Weekly 679, February 26–March 3, 2004).

Rachel Aspden, “Living with the Monster,” New Statesman, December 4, 2008.

“Made in Iran” exhibition flyer, 24th June – 11th July 2009, curated by Arianne Levene and Églantine de Ganay, Asia House, London.

In 2002, when I showed What Has Befallen Us, Barbad? in New York, it was written here and there that the locks of hair in the piece resemble arabesque calligraphy.

Agents and consultants of an auction visited an Iranian abstract painter. They told him “your paintings are really beautiful but we can sell them only if you use a bit of calligraphy.”

See →.

Like any other narrative absorbed into common sense, “westoxication” or “Occidentosis” was once a theory. For example, see Jalal Al-e Ahmad, Occidentosis: A Plague from the West (Gharbzadegi), trans. R. Campbell (Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press, 1983).

See →.

I should say that after our recent riots and protests this imagery has changed.

This led to the execution of thousands in one summer and offered up an archetypal embodiment of Heterotopia: Khavaran cemetery.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, ed. Rolf-Peter Horstmann and Judith Norman, trans. Judith Norman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002) 69.

The outlines of this paper were first discussed at the 2007 Festival d’Automne à Paris roundtable “Pratiques esthétiques contemporaines : productions, enjeux et publics,” with Catherine David, Lina Saneh, Joana Hadjithomas, Khalil Joreige, and Abdellah Karroum. In May 2009, at the invitation of Dr. Sarah Wilson, it was presented at the Courtauld Institute of Art as “Barbad Golshiri in Conversation with Layal Ftouni. ‘Unveiled: Dismantling or Reproducing the Orientalist Canon?”