Universe I see your face looks just like mine…

— The Microphones, “Universe”

It can be difficult today to reconcile oneself with modernist ideals that seem to still contain some liberating promise, considering how in practice so many of these ideals have proven to be ineffective at best, and quite oppressive at worst. Likewise, while ideological systems that accompanied these ideals are no longer reliable, their straightforward certainty and romantic clarity of purpose somehow remain captivating prospects for relieving some of the anxieties found in distributed, competitive systems of negotiated and renegotiated value. After all this time, we are still seduced by modernism’s emancipatory promises just as we are stifled by its models of democratic managerialism.

The field of art not only suffers from these unreconciled desires and realities, but often finds itself in the uncomfortable position of having to negotiate with them in order to ensure its very existence. But in this negotiation, the variables always seem to slip out of one’s grasp: the rediscovery of ideology gets pitted against the melancholia of its collapse; the desire to be instrumental beyond the field of art is bracketed by a fear of being instrumentalized by those same forces; assertions of artistic autonomy translate into performative disappearance; straightforward engagement risks severe compromise—all of this to try and access a latent and bonding value in art, whether on its own terms or in collaboration with the forces to which it is subject. There is no real solution to this, but then again, these are not necessarily problems either.

But these conditions do describe a degree of discomfort and a general sense of mistrust with regard to art’s capacity to generate its own value, and it might be useful to think a bit about ways in which art can be less subject to conditions that are often conflicting and confusing by advancing some form of universal significance to be found in the artistic act. Though this would necessarily borrow from certain ambitious universalist claims found in early modernism and beyond, this understanding would inevitably have to constantly disengage itself from the strictures of any particular authority or framework that would limit its movement or threaten to revoke its consideration as art. This is to say that it would have to rely mainly on the same unreconciled and distributed subjectivities mentioned above. Though this may sound like a slightly paradoxical thing to expect, thinking further about how it might be possible could release some of the pressure of the less productive and confusing paradoxes that art confronts us with today, and could even comprise an attempt at accessing some of the emancipatory promises that got us here in the first place. A couple of texts from the last issue of e-flux journal may be of help here.

Disengagement

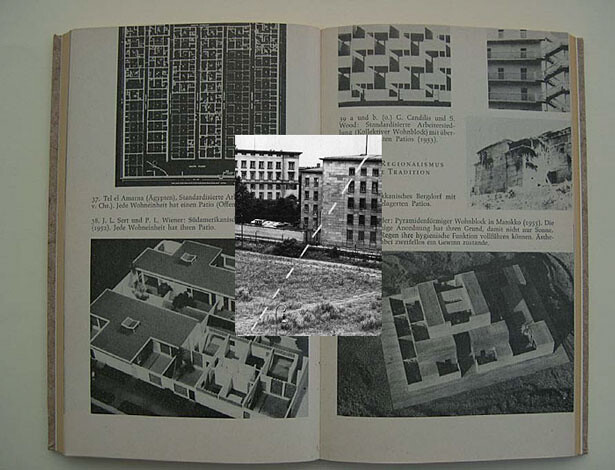

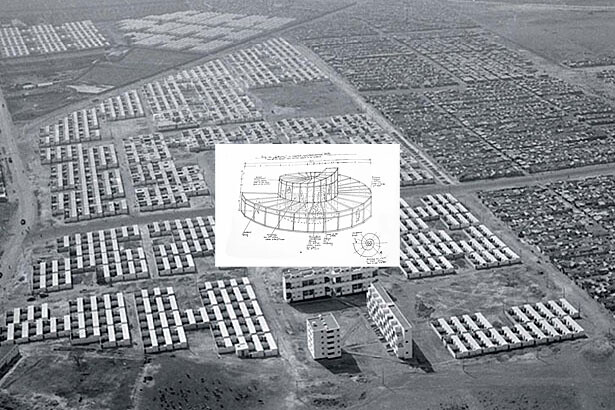

In issue #6, Marion von Osten’s “Architecture Without Architects—Another Anarchist Approach” looked at how modernist urban planning projects in the French colonies, while built with the intention of liberating their inhabitants, became inadvertently used to control and limit their movement, mechanizing subjects around a strict top-down logic of control.1 Though the architects of these projects imagined themselves as gracious liberators, it seems as though they overlooked a crucial flaw in the modern project: that no central plan is really going to liberate anyone, much less one transposed from one society onto another. As a natural consequence, inhabitants of these buildings and urban grids began to appropriate these structures and, using improvised building practices, absorbed the logic of the grid into one that worked for them.

Von Osten suggests that their resolution comes from their breakdown into informal, negotiated systems of horizontal exchange in which universal modernist forms are abandoned altogether, often by inhabitants who return these notions back to real life. In many ways, it seems this is the direction in which things are headed: if modernism’s emancipatory promises are to have any degree of sustainable relevance, it makes much more sense to consider these promises not as something granted by a central authority to subjects down below, but claimed by those very subjects using an assortment of available materials in ways that could not have been imagined by a central planner.2 The pure formal vocabulary that modernism offered as a complete project from start to finish was accepted only on the basis of being an incomplete skeleton—a shell of an idea that would not be complete until it could be inhabited by something else. In essence: it now seems clear that if any system is to carry any sort of liberating capacity, it has to lay the foundation for the subject to claim his or her own means of finding freedom—to some extent, one has to reconstitute the system for oneself.

Here, self-building works as an interesting blueprint for a means of disengaging from a structure of meaning without literally or physically abandoning its premises. Beyond the purely resistant dimension of these actions, there is a latent energy in self-building that also reflects modernism’s own irreversible transformative capacity—total in its breadth and inescapable in its weight. Insofar as it is a response to the logic of the central planner, so does self-building likewise form an extension to the plan. In a sense, one could argue that every gesture within an experimental laboratory is itself an experiment. And if these experiments do indeed automatically surpass their original intention, they can be considered within a broader frame of significance. Taken this way, the repurposing of a central plan by its inhabitants does not replace a universalist conception with a kind of small-scale pragmatism of a withered subject picking through the wreckage, but rather opens up an entirely new field of possibility in the understanding that each response to the failure of the central plan constitutes its own universalist claim. The idea here is not to find a container to accommodate these—to reinstall the role of the planner—but to suggest a more ecstatic sphere that can unlock these possibilities or disengage them from their purely pragmatic foundations.

“But perhaps they still understood that the most radical form of design emerges when the people begin to represent themselves without mediators and masters.”3

While self-building is testament to the death of a certain type of author—the architect of large-scale urban projects—it can be interesting to imagine this phenomenon not in terms of an absence of authorship or authority, but more in terms of its widespread distribution. Since one is certainly not lost without the central planner, surely authorship is still in play somehow. And if this authority shifts to the realm of the subject, then though the subject may only have the space of a single unit, a single block within the grid to work with, what could be interesting would be to suppose that the small-scale strategies that emerge in opposition or response to the central planner can parallel modernism’s scale and reach in the power and ambition of their vision. Though these responses may not even necessarily be destined for concrete implementation in a real setting, i.e. their power may lie completely within the symbolic realm, one can suggest them to be no less ambitious than those of Corbusier himself, which is to say that a small-scale response can contain an entirely new central plan within its logic.

What modernism never took into account with its idea of the universal subject was in fact the subject’s own universe. Granted, this is what the slightly paradoxical idea of “open plans” sought to liberate, but more importantly, self-building simultaneously calls out the bluff and the promise of modernism’s surface by replacing the logic of central authority with the development of subjective worlds inside and around the units of the grid. One could say that the aesthetic terrain that provided this promise still retains it. In other words, when we find failure in the implementation of the model, we perhaps fail to recognize the latent energy within the model itself. And claiming the means to direct this energy has less to do with modernism than with the terrain on which we locate the material of cultural work, and here things begin to return to art. Because what we are implicitly looking for here in the absence of centralized forms of legitimation is a logic for understanding how artistic works might find their own legitimacy without having to resort to a central authority to grant it. While this begins with a break from that authority, how does one then start to think about reconstituting that legitimacy in its absence? Perhaps by looking to the latent energy that surrounds such a claim to legitimacy at its inception, and by thinking about a kind of displacement that might already have marked a gesture as art before it was even aware of itself.

Your Legitimate Claim

Utopia, through the abolition of the blade and the disappearance of the handle, gives the knife its power to strike.

— Jean Baudrillard, Utopia deferred…4

So far, I have tried to identify a potential for a universalist significance in small-scale or marginal responses to a social system, yet the problem is that this claim remains trapped in the space of a subjective projection—within, say, a single apartment in a grid of housing projects. In the last issue, Mariana Silva and Pedro Neves Marqes’ text “The Escape Route’s Design” explored the embedded potential of artworks to escape the dead space between the indeterminacy of an artistic proposal and the overt instrumentality of pragmatic social engagement or concrete political action.5 This may be an opening through which an artwork might to some degree assert its own inherent value, or rather, in their words, “the continuous affirmation of the possibility of exchange value beyond the gathering of consensus or multiplicity.” While in the end, their assertion is highly reliant upon the dynamics of this multiplicity—that of an individual subject within a cloud of potential possibilities—they attempt to take things a step further with a claim to this individual’s freedom to reconstitute the meaning of artistic work. But this freedom is not only activated by a simple matter of the subject asserting a will or a desire for an act to be considered within a broader frame of significance (though surely this is a part of it), but is also an assertion of a latent set of conditions—conditions that might be invisible, sleeping, inert, or displaced—that together comprise a more objective, however speculative means of legitimating an artistic act as such. It is a matter of aligning this act with the conditions that make it possible as art—similar to what the Kabakovs called the “sudden occurrence” that renders an unsuccessful project a successful one—that grants its legitimacy. And this alignment can be a simple matter of a shift in perspective.

All of this together represents a long and arduous process where repeatedly selected variations and “sudden occurrences” participate simultaneously. In this sense, it is impossible to refer to any project as unsuccessful—it can only be referred to as an unsuccessful variation of something which in a different altered view or with a shift in components, in a word, a “sudden occurrence”—will turn out to be the correct resolution, absolutely successful.6

In the text, Silva and Marques compare Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s Palace of Projects to various strategies for crossing the Berlin Wall unnoticed. Where The Palace of Projects was a large structure that contained sixty-five displays of sculpture and schematic drawings suggesting larger scale artworks, actions, ideas, or statements, all yet to be realized, the “attempts at crossing the Berlin Wall in its verticality,” while similarly speculative in nature, were for obvious practical reasons intended solely to be executed in real life.7 Yet for Silva and Marques, both of these “projects” converge in their allusion to an action that lies just further afield, and is to varying degrees realizable or unrealizable. The Palace of Projects maintains a fundamentally utopian structure in that it always projects the completion of its projects into the future, and is from its outset, reconciled with its own impossibility. The proposal suggests a possibility, but then stops short: “the realizable is enmeshed in the unrealizable,” and in this admission, The Palace of Projects, seen in its totality, becomes no more exemplary of something beyond itself than any monument.

On the other hand, the attempts at crossing the Berlin Wall comprise a similar schematic presentation, but with a radically different intention aimed at a literal application of what it illustrates: how to simply escape the GDR unnoticed. Likewise, if there is any utopian potential to be found embedded in these schematics, it is similarly negated by their intention towards actual, pragmatic action. However, when overlaid with the Kabakovs’ proposals, Silva and Marques find in the possibility of Berlin Wall crossings’ real world actualization an immanence that can cross over to also legitimate the Kabakovs’ proposals as not only possible, but as having already taken place. This acknowledgement can come from aligning the proposed action with a set of conditions that have less to do with the kinds of consensus that legitimate objects and events within the realm of the real, but that have more to do with those that make objects and events themselves highly speculative and potentially incomplete. To draw a parallel to von Osten’s self-builders, the self-built responses to modernist urban planning projects can be seen as themselves entirely new urban plans when they (or I, for that matter) invoke the modern grid as itself a speculative object, incomplete in its nature, and therefore contingent upon such interventions for its own entry into a sphere of completion. But how do we then invoke this incompleteness, or project it onto such structures? Where do we locate these weak points in the alleged completeness of built projects?

One way is to locate the invisibility of many projects’ completion. Silva and Marques point out in the case of the Berlin Wall crossings that, in the act of crossing through covert means, without the notice of the authorities, the completion of the project was effectively hidden, although in every real sense it had actually taken place.8 The physical act of passing a body from the GDR to the West needed, and even required no audience to qualify its validity as action. To invoke this example would be to assert not only that projects are built and “un-built” without the necessary position of a spectator, but also that it is impossible to say for sure what has or has not been completed, if indeed we accept that real events can take place without our knowing.

By removing the audience from its role in validating an act, Silva and Marques open things up significantly to a myriad of readings. And it is with this in mind that they propose a kind of legitimacy for The Palace of Projects that passes its claim retroactively from the sphere of a proposal to that of the actual. This claim does not so much assert that a monument is built (though we cannot say with absolute certainty that it is not), but rather asserts that built monuments themselves are not necessarily complete, or have not yet fully achieved their own projected intentions within a real sphere.9 In this sense, art draws the real back to itself—art becomes no longer subject to the real, but rather reality becomes subject to art. Furthermore, The Palace of Projects can be said to have already built its proposed projects by, metaphorically speaking, smuggling them through a checkpoint in the Berlin Wall.

Finally, for Silva and Marques, it is ultimately “through the prism of free attribution of value, kaleidoscopic in form” that the individual aligns an artwork or isolated instance with its expanded significance, whether in a social sphere or beyond. If we are to then take for granted that this attributive license is granted to anyone at any time, then why does the negotiation of artistic value present itself as such a burden? Perhaps it has to do with the void opened up by such an arbitrary distribution of meaning. But to then return back to von Osten’s self-builders, any promises of free attribution made by the central plan will never be granted by that plan. Though it may implicitly hold the potential for a small-scale response to comprise an entirely new plan through the free attribution of pragmatic or artistic value, this potential must somehow be activated.

Marion von Osten, “Architecture Without Architects—Another Anarchist Approach,” e-flux journal, no. 6 (May 2009), →.

See Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza’s contribution in issue #6 as well for a detailed account of this dynamic: →.

von Osten, “Architecture Without Architects—Another Anarchist Approach.”

Jean Baudrillard, “Utopia deferred…” in Utopia Deferred: Writings for Utopie (1967–1978), trans. Stuart Kendall (New York: Semiotext(e), 2006), 62.

Mariana Silva & Pedro Neves Marques, “The Escape Route’s Design: Assessment of the Impact of Current Aesthetics on History and a Comparative Reading Based on an Example Close to the City of Berlin,” e-flux journal, no. 6 (May 2009), →.

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, The Palace of Projects, excerpt from text written in There are No Such Things as Unsuccessful Projects.

See detailed documentation of each project with translations of text in the drawings here: →.

“The performative character of these events would then simultaneously translate into a non-commensurable action, a production of meanings and free spaces, conditions and acts of self-identification, precisely through this absence of an intentional audience, the absence of a predefined performative structure; therefore of a demonstration understood as conscious and intentional, as is frequently the case in the production of artistic value, quantifiable and quantified by law. This exemplary character is then paradoxically extracted from its own characteristics of un-example, namely its unformed and undetermined characteristics, foreign to any commensurable regulation in the effective making of the action. … The effective act of crossing the Berlin Wall distances itself thus from the Palace of Projects, given that only when the monument, itself a symbol of aspiring potentiality, is effectuated through the attempts at crossing the Berlin Wall, is it accomplished in Life. Nevertheless, this recognition of the symbolic diluted in life, that is, unrecognizable as such while it occurred, would implicate the negation of the proper identity of monument, its understanding as such, given that the permanence of its status would necessarily make its de-signified establishment in the world impossible. Solely by denying the monument its proper self-referential status as monument could it perhaps, differentiated by this precise negation, permit its own dissolution in the life-world”

“Accordingly, and in view of the state of democratic negotiability of value mentioned above, one is confronted with a situation in which history seems to reply retroactively to the proposals elaborated by the Kabakovs’ authors, precisely by the particularity of the attempts at crossing the Berlin Wall in its verticality. The cases of escape from the Soviet regime, perpetuated by numerous people during a determinate period in time, by transgressing the boundary of the Berlin Wall, is equivalent to an equal or corresponding innumerability of projects, whose conception and realization, of individual or collective design, could then constitute an answer or a historical counterproposal to the Kabakovs’ projects. This response, as counterproposal, is given by its exemplary character in opposition to the previously cited demonstrative enunciation of the artist. Put differently, the character of the aforementioned events imposes precisely and necessarily the will or act of taking the design in hand, no longer understood as a project or model but as the physical actuality of an act in its simplicity of idea. With a multiplicity of common objects used for and during its concretization, it does not cease to propose its execution to each inhabitant, individually and without exception. … That the meaning found in the Palace’s proposals would have been extrapolated in their unfinished condition and consequently demonstrated a real existence of these individual gestures of social significance, in that the referred projects would have already, truly, at a given moment, and even if in another time and by other means, been effectuated.”