While questions of creative sovereignty (hurriyat al-ibda‛) tend to loom large in Egyptian academic writings, the artistic trajectory of the annual juried competition known as the Youth Salon has been marked, historically, by structural inertia. Established in 1989 by the Ministry of Culture, the exhibition was meant to encourage a new generation of Egyptian artists and increase their international visibility.1 Jessica Winegar has explored the Salon as a “tournament of values” that is part and parcel of struggles surrounding the “shared ideal of the patron state.”2 Indeed, if the space of the exhibition is understood, as Boris Groys argues, as the “symbolic property of the public,” then the debates surrounding the 2009 Salon illuminate the contested nature of artistic and curatorial sovereignty in the shadow of the legacy of state socialism and a purportedly democratic mass culture of artistic consumption and production.3 An exploration of the controversies that erupted around the selections of the jury committee, the curatorial strategies employed in the exhibit, and the political reverberations of specific aesthetic choices, can elucidate the ways in which artistic and curatorial sovereignty can be forged in a range of historical circumstances—postcolonial, postsocialist, and beyond.

Due in part to the intense pressures placed on Egyptian artists to perceive entry into the Salon as indexical of future success, in part to the historic entry of a sizeable numerical percentage of artists into the Salon, the extreme selectivity of this year’s competition was reported in the mainstream press, even before the official opening, as an affront to the democratic nature of the exhibit.4 This year’s jury, critics declared, had substantially narrowed the pool of artworks exhibited, rejected previous Salon winners, and subverted the expectation that an aesthetic of new media art would dominate the exhibit to the extent that the Salon would constitute a radical break from previous years. Critics of the Salon cited the original Paris Salon des Refusés of 1863, convened to allow public viewing of 3,000 rejected works of art, and referred to the March event in Cairo as a “crisis”—one that cast doubt on the ability of the judges to arbitrate artistic value.5 Yet, even in the past, the inclusive gestures of the Salon have, according to its critics, concealed the way in which certain aesthetic choices, particularly those that conform to the contemporary international biennial style, have been promoted through the yearly Salons.6

Rather than simply view the Salon as embodying conflicts between generations or around identity politics, I argue that the disputes surrounding the arbitration of aesthetic judgment were coded as a series of binaries: local–global, government sponsored–artist sponsored, authentic–contemporary, and nationalist–neo-liberal. Such binary representations seek to unequivocally categorize art, and mirror authoritative public discourse on art in Egypt, which seeks to delegitimize forms of artistic production that do not conform to the imperative to produce artistic work that is at once contemporary and nationalist, or at least identifiably “Egyptian.” Clearly, similar parallels may be found elsewhere in postcolonial and/or postsocialist contexts. Thus, Igor Zabel has discussed the Russian context and the curatorial constraints surrounding the presentation of works of art that cannot be seen solely as art, but must always be inflected by their locale (revealing a “Russian essence,” for example), while Western art alone is considered as icon of “contemporary art.”7 While all contemporary art is clearly “constitutively stained” by its location, only non-Western art is expected to have questions of identity function as a touchstone.8

The adjudication of aesthetic value is, of course, connected to institutional structures. The Ministry of Culture, founded in 1958 and itself a legacy of state socialism, sponsors the yearly salons as well as a formidable infrastructure of national galleries, viewing itself as the official arbiter of artistic production and consumption in Egypt. The recent influx of privately owned or artist-run gallery spaces and initiatives (quite different from their historical predecessors in their international outreach) mirrors the surge of interest in artists from the region and has complicated the picture substantially.9 This has enabled an entire range of artistic practices that straddle the divide between the Ministry of Culture national art circuit and the less formal domain of privately owned gallery spaces. These practices range from the public to the informal and impromptu (for example, artistic interventions that take place in dynamic urban settings, such as kiosks or mechanic workshops) and exist alongside and in conjunction with the national art circuit, but are not necessarily embedded in the same sets of debates. Such artistic production need not be viewed in isolation of the state sanctioned public realm, since many artists operate within multiple spheres that often intersect and overlap.

Crucially, the 20th Salon appointed for its eight-member jury three successful contemporary artists and curators (whose work has circulated both inside and outside the Ministry of Culture circuit) who can be said to be a vital part of this artistic “third space.”10 It is unsurprising, then, that the local and international repute of the artists on the jury was consistently referenced by critics. Was appointing individuals who purportedly represented the global biennial style a conscious and transparent effort on the part of the Ministry of Culture to co-opt successful elements operating outside their circuit? Or was it a genuine attempt to explore artistic production occurring within what has become an increasingly vibrant artistic sphere? Regardless of the MoC’s intentions (and of course intentionality is hardly a useful way in which to view institutional decision-making processes), we can gauge the effects (many of them unintended) of this decision on public art discourse as well as on broader notions of curatorial and artistic sovereignty.

In part due to the virulent negative response of the mainstream media and art establishment to the selections of the 2009 Salon, the decision of the three members to convene an open panel to disclose the aesthetic choices of the committee speaks to the need for public justification and accountability at the conceptual heart of the Salon.11 Many of the critiques of the 2009 edition centered on upsetting institutional boundaries and protocol, mobilizing many of the aforementioned binaries to delegitimize the jury. Thus, critics noted the “youthful” nature of the jury, the absence of any formal affiliation between them and the MoC as an institution, their aesthetic affinity with Western-oriented private gallery styles, their subversion of past jury decisions, and internal differences of opinion within the jury itself—in order to undermine the jury’s competence and coherence.12 In so doing, such critiques pitted the jury against a purportedly uniform culture of aesthetic judgment that was both government-sponsored and nationalist in its orientation.

Thus, among the key points of contention during the open panel was the decision of two members of the jury—Hassan Khan and Wael Shawky—to curate the exhibition (a role traditionally reserved for the MoC), rather than confine themselves to judging artworks. While this insistence upon taking responsibility for both the selection and the exhibition of the works yielded a large degree of curatorial sovereignty (understood as independence from the institutional domain of the Ministry of Culture), such sovereignty was likewise tempered by a willingness to justify their choices to an angry public of artists, curators, and institutional members. Reflecting what Boris Groys has described as “the institutional, conditional, publicly responsible freedom of curatorship,” this concession to the public nature of curatorial work was further underscored by these jury members’ agreement with the MoC to publish a book detailing the theoretical rationale behind their curatorial decisions.13

In their public justification of their work, the committee members focused on several key points: the creation of contemporary non-derivative art, the formation of a public exhibition culture based on selectivity, and the intensely heated question of artistic mediums. The strongest critiques levied against the jury selections were related to the question of mediums. Historically, the privileging of particular mediums has always drawn the ire of the art establishment, for example in the form of melodramatic proclamations of the “death of painting” and the concomitant privileging of installations and new media practices. But this year’s exhibit confounded expectations that the jury would choose a preponderance of installation pieces or video work (in fact, only a handful of these were selected)—work that most closely conforms to the reigning conception of contemporaneity. Thus, the selection of a large number of works using “traditional” media such as figurative painting meant that such stock criticisms could not be levied against the jury.

Indeed, the jury cogently argued that the defensive emphasis on contemporaneity led to both the overvaluation of aesthetic mediums themselves as well as the derogation of the creation of a formal personal language in art. The issue of contemporaneity returns us to Igor Zabel’s questioning of the implicit equation of “Western” and “contemporary” art within art historical criticism.14 Indeed, one can argue that this is linked to a much longer-standing Enlightenment historical tradition that Reinhart Koselleck has referred to as an assertion of the “noncontemporaneity of the contemporaneous,” that is to say, the notion that multiple histories, although occurring simultaneously, became “nonsimultaneous.”15 This is most clearly found in common perceptions of a temporal “lag” in the artistic production of the second and third world, and the notion that these regions will eventually “catch up” to purportedly more contemporary artistic and conceptual practices such as installation and video-based work.16 In rejecting the notion that contemporaneity could be equated in any way to new media practices alone, the jury thus disrupted a common perception that contemporaneity could be reduced to a choice of materials alone, arguing instead for a criteria locating works’ currency or relevance in more complex and less reconciled approaches.

Clearly the Salon and the controversy surrounding it revealed a complex relationship between public and private drives, constituting a specific instance of a counter-public discursive moment.17 Thus self-preservation on the part of the Ministry, as sole arbiter of artistic value, was justified in the name of the public; just as counter-public gestures (those of the jury) were justified through a complex mix of private intention and public necessity, namely, the creation of an independent contemporary art movement in Egypt.18 This is in keeping with Boris Groys’ contention that curatorial work is in large part related to the mediation of public opinion and the formation of a mass culture surrounding art.

But what becomes of artistic agency in the midst of such complex jockeying for access to public space and recognition? The 20th Salon is perhaps best understood as a momentary rupture in which artistic agency can be viewed not as emanating solely from the capacity of a sovereign subject who wills, but rather as the contingent product of a series of historically constituted events. Rather than view artistic agency solely as “the sovereign, unconditional, publicly irresponsible freedom of art-making,”19 we can conceive of artistic agency—like human agency itself—“not as a calculating intelligence directing social outcomes but as the product of a series of alliances in which the human element is never wholly in control.”20 Artistic agency thus emerges from a complex assemblage of sovereign will, historical and structural constraints, opportunity, and mere chance. The emergence of conditions conducive to such agency have long been in the making, and are not to be seen as having been instantaneously produced by the 20th Salon. Rather, such conditions are related to a complex of historical factors, namely, the demise of state socialism and related attempts to centralize artistic production and consumption; the rise of neo-liberalism and the concomitant creation of privately owned and oriented gallery spaces; and, most importantly, the emergence of artistic production that has sought to move away from both the earlier antiquated state socialist model and the politically irresponsible neo-liberal model, marked by the creation of homo economicus.21

The interstitial location of many contemporary artists, between the state-socialist and neo-liberal models, has in fact accentuated disputes over artistic agency and autonomy. Indeed, the entire question of the autonomy of the artist came under fire in the Egyptian press, in terms that expose the legacy of state-socialist discourse. Usama Afifi, an art critic, railed against the notion of complete creative freedom (hurriyat al-ibda‛ al-mutlaq), arguing that there is no such thing as absolute freedom, that all freedoms exist rather within societal constraints and that art should serve the needs of society.22 In particular, he argued, art should address the major issues of the day that plague Egyptian society, rather than merely aping the West.23 Thus, artistic freedom, according to Afifi, was related solely to mediums and methods. The confining of autonomy to materials and methods, while placing the thematic content of art within the domain of societal obligation, not only adheres to the general principle that art must address the social and political issues of its day, but similarly confines art to the ethics of socialist realism.

Clearly, artistic autonomy occurs within particular social contexts; arguably, within a postsocialist context, the notion of the autonomous artist is not as celebrated as in the West, in part because of the bourgeois associations with the idea of “freedom.”24 But if we return to Groys and view autonomy not as completely unconditional and sovereign, but simply as the “publicly irresponsible freedom of art-making,” we can conceive of artistic autonomy in the Egyptian context as entailing a move away from the confining hegemonic public discourse surrounding the “traditional and the contemporary” and the constant need to assert the authenticity and contemporaneity of one’s art. At the same time, however, the pieces selected for entry could not be further from creating the neo-liberal autonomous subject that many claim contemporary Western curatorial practices in the Middle East and elsewhere seek to create.25 The production of subjectivity, as Jason Read has argued, is in fact central to neo-liberalism and may be understood as the creation of a subject of interest (a self-interested individual), locked in competition.26

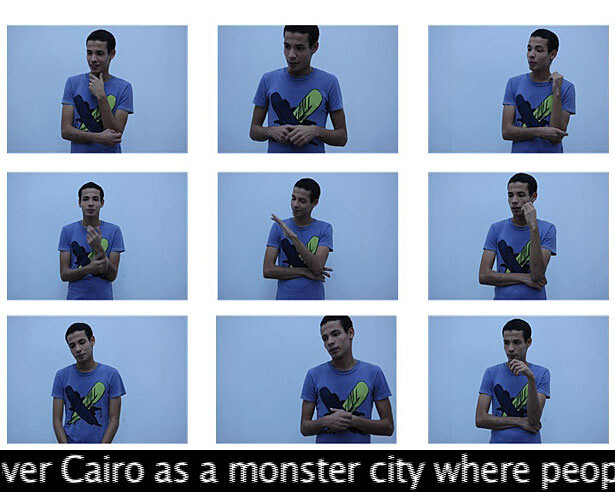

Nowhere was this subversion of neo-liberal subjectivity more evident than in Mohamed Nabil’s clever video installation Interview with Three Artists, consisting of a series of three video vignettes: “The Lebanese Artist,” “The Egyptian Artist,” and “The Palestinian Artist”—all played by Nabil himself. The piece self-consciously questions the role of the artist and the effects of self-representation, and subtly—implicitly, even—demonstrates the way in which a complex of curatorial decisions, and the need for artistic recognition and success, structures contemporary artistic production in the Middle East along stereotypical and conventional lines. Thus the Lebanese artist discusses the effect of the Lebanese civil war on his art and on collective memory; the Egyptian ruminates on the effects of life in a mega-city such as Cairo on notions of private and public space; and the Palestinian discusses how he would like to integrate the concept of a wall and a “country without any walls” into his work. One need only think of the contemporary success of certain Middle Eastern artists (and the curatorial decisions that buttress that success) to realize how acute and piercing Nabil’s piece is. “Art,” Hannah Feldman and Akram Zaatari insist, cannot “be made to represent geo-political identities without falling back on extreme simplifications.”27

In his playful destabilization of artistic agency and autonomy, Nabil demonstrates the way in which the neo-liberal artistic subject is the artifact of the structural constraints of the art market and of the historical forces that shape its wider perception of the Middle East region (for example, the Lebanese civil war) and therefore the possibility of success within that market. Thus, the piece demonstrates a post-nationalist sensibility, but one that clearly cannot be equated with neo-liberal subjectivity. This belies the assertion of separate, dichotomous, spheres of art, particularly as related to the assumption that so-called Western-oriented artists and the MoC prefer a contemporary style based on video and installation mediums that promote a neo-liberal subjectivity. Rather than the reductive binaries of “nationalist” versus “neo-liberal,” it may be more useful to understand the Egyptian art scene, like other art scenes, in terms of publics and counter-publics that are not necessarily isomorphic with “nationalist” and “neoliberal,” but rather complexly formed fields that are co-constitutive and exceed their terms of reference.

In the same gallery as Nabil’s installation were Lamia Moghazy’s massive painting of a television screen replete with animated and human icons and Ahmed Badry Aly’s massive construction of silver painted blocks (Suni’a al-sin [Made in China]). Their monumental size meant that they could best be viewed (and read) from the height of the exhibition site. Conceptually, their deconstruction of neo-liberalism and globalization were clear to all but the most recalcitrant of reviewers. It was, however, the curatorial decision of the jury to place these two works in a position of great prominence—as the first works encountered upon entering the exhibit—that upset reviewers.28 Moreover, the monumental size of both pieces was in clear contrast to the selection of smaller sculptures that were placed serially and below eye level in a less valorized position on a top-level gallery floor. The de-monumentalization of sculpture, what critics referred to as its “marginalization,” was taken as an affront to one of Egypt’s longest-standing arts (and to the antiquity of its claim to the visual arts)—a critique voiced even among reviewers sympathetic to the focus on new media arts and contemporary artistic practices.29

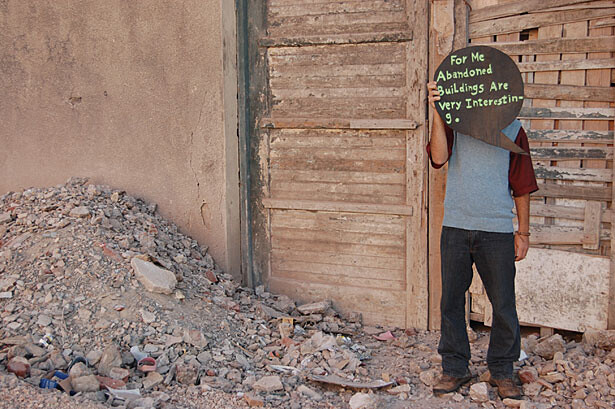

These sculptures were placed in dialectical tension with Mohamed Ahmed Mansour’s Godard-like photos, which exhibited an awareness of the constructed nature of artistic subjectivity. In a series of photographs titled, “It could be a family album, it could be not,” Mansour situates himself in a series of locales, such as a gas station, a supermarket, and an abandoned building, with speech bubbles containing statements on the order of “Nothing special it’s just an old fashioned coffeeshop,” “For me abandoned buildings are very interesting,” “I do like historical places,” and “It’s my favorite gas station”—thereby self consciously placing the role of the artist at the forefront of the work.

Also highlighted in the works chosen for the exhibit were the fetishization of progress and contemporaneity within hegemonic public art discourse. In Sounds Cells: An Electro-Magnetic Orchestra, Magdi Mostafa explored electromagnetic square-wave sound technology used in the 1950s and 1960s in a cellular structure placed in a darkened room. Rather than simply being an homage to an anachronistic earlier sound technology, its visceral and reverberating sonority—felt throughout the exhibition halls—was a reminder that art need not be enslaved to the postcolonial desire to undo the “noncontemporaneity of the contemporaneous.”

The sonority of Sound Cells was matched by that of 80 Million (the proverbial population of Egypt), in which Eslam Zen Elabden and Mohamed Hossam produced a prize-winning video installation in which the frenetic and infectious sounds of the tabla filled the gallery space while onlookers came to notice the duo drumming—in perfect musical synchronicity—without drums. 80 Million is remarkable in its pared-down evocation of place, refusing to conform to the fetishism of authenticity through mega-cities and masses, choosing instead as its medium the circulation of energy, both real and imagined.

The evocation of place was further explored in Faten Dessouki’s performance piece in which she recreated a traditional ahwa (coffeeshop) with numerous chairs and tables on a platform centered around a television set. Dessouki’s intention was to create a performance centered on the everyday urban practice of “people watching television in public spaces.” The piece functioned brilliantly as a performance without a performance artist. The actors chosen by Dessouki wandered for a time through the exhibition space but before long fixated on this space, taking seats and creating their own spontaneous and impromptu café in the midst of the gallery.

Altogether, many of the pieces in the exhibit could be considered attempts to “escape from the game of representations, from the position of being others’ other.”30 In so doing, they served as a crucial reminder that art reduced to the status of geo-political identity politics is evacuated of all meaning. In the end, the 20th Salon will be remembered by its opponents as an example of how the Ministry of Culture failed to control its own exhibition space; but for those sympathetic to the jury’s work it marked the possibility of expanded artistic and curatorial sovereignty, however limited, and the hope of a conversation to come.

Ministry of Culture, hereafter abbreviated as MoC.

Jessica Winegar, Creative Reckonings: The Politics of Art and Culture in Contemporary Egypt (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006), 158, 161.

Boris Groys, “Politics of Installation,” e-flux journal, no. 2 (January 2009), →.

Only 101 artworks were selected out of a total of 1,293 submissions, as against the usual 300 or so.

“Salon al-shabab al-‘ishrun bayn al-tajdid wal-taqti‛a” (“20th Youth Salon: Between renewal and disruption”), Ruz al-Yusuf, April 12, 2009, 14.

For an overview of these criticisms, see Winegar, Creative Reckonings, 158–174.

Igor Zabel, “We and the Others,” Moscow Art Magazine 22 (1998) →.

See Saba Mahmood on Judith Butler’s discussion of the way in which theoretical formulations, purportedly universal and abstract, are “constitutively stained” by their examples, in Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 163.

Such as the recently founded (2004) Contemporary Image Collective in Mounira, Cairo, “founded in 2004 by a collective of artists and professional photographers, focusing on the visual image and the development of contemporary visual arts and culture in Egypt.” See →.

The members of the 2009 Youth Salon Jury were Hend Adnan, Sahar El Amir, Bassam El Baroni, Hassan Khan, Mohamed Radwan, Moataz El Safty, Wael Shawky, and Ahmed Shiha (President of the Jury).

The panel took place the day after the official opening on March 30, 2009, and included: three of the members of the Salon jury committee, Bassam El Baroni, Hassan Khan, and Wael Shawky; Mohammed Tala’at, the director of the Ministry of Culture’s Palace of Arts; the head of the jury committee, Ahmed Shiha; and the head of the Fine Arts Sector in the Egyptian Ministry of Culture, Mohsen Sha’alan.

Samar Nawar, “Al-mustab‛idun min salon al-shabab yuftahun al-nar ‛ala lajnat al-tahkim wa wizarat al-thaqafa”[“The Refusés of the Youth Salon open fire on the jury committee and the Ministry of Culture”], Al-Badil, April 2, 2009, 12; Fatima Ali, “Salon ‘lajnat al-tahkim’ wa laysa ‘salon al-shabab’,” [The ‘Jury Committee Salon’, not the ‘Youth Salon’”], Al-Qahira, April 14, 2009; Salah Bisar, “Salon al-shabab al-ishrun…dawra dun al-mustawa,” [“20th Youth Salon…A session without quality”], Al Qahira, April 21, 2009, 15; “Salon al-shabab al-‘ishrun bayn al-tajdid wal-taqti‛a” [“20th Youth Salon: Between renewal and disruption”], Ruz al-Yusuf ; Dina Sadiq, “Dawra bahta min salon al-shabab” [“A perplexing session from the Youth Salon”], Al-Shuruq Al-Jadid, April 6, 2009, 12.

Groys, “Politics of Installation.”

Zabel, “We and the Others.”

Coexisting cultural levels could then, through synchronic analysis, be ordered diachronically, within the framework of a universal “world history.” See Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, trans. Keith Tribe (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), 231-288.

See, for example, Laura U. Marks, “What is That and Between Arab Women and Video? The Case of Beirut,” Camera Obscura 18, no. 3 (2003), 43–44.

I am using the term “counter-public” discourse to refer to practices that are oppositional to normative hegemonic public art discourse in Egypt, which focuses on the creation of a contemporary artistic movement that is rooted in a (national) identity-based sensibility.

I thank Brian Kuan Wood for bringing this point to my attention.

Groys, “Politics of Installation.”

Timothy Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-politics, Modernity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002), 10.

The period of state socialism in Egypt is usually designated as 1952–1970. Economic liberalization is said to have begun with Sadat’s 1974 “open door” economic liberalization policy. Jason Read develops Foucault’s idea of homo-economicus as defined by an anthropology of competition (rather than exchange, as in classical liberalism) in “A Genealogy of Homo Economicus: Neo-Liberalism and the Production of Subjectivity,” Foucault Studies 6 (February 2009), 25–36.

The phrase “total creative freedom” was used in the introductory essay of the Salon’s catalog by Commissioner George Fikry, and was part of the open call that was sent out for the annual competition.

Usama Afifi, quoted in “Salon al-shabab al-‘ishrun bayn al-tajdid wal-taqti‛a.” See also Nawar, “Al-mustab‛idun min salon al-shabab yuftahun al-nar.”

See Alexei Yurchak, Everything Was Forever Until It Was No More: the Last Soviet Generation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 10–14, on Lefort’s paradox of socialist ideology, exemplified in the “objective of achieving the full liberation of society and individual … by means of subsuming that society and individual under full party control.” See his discussion of the book Marxist-Leninist Theory of Culture and the idea that “in the socialist context, the independence of creativity and the control of creative work by the party are not mutually contradictory but must be pursued simultaneously” (12).

Winegar, Creative Reckonings, 156.

Read, “A Genealogy of Homo-Economicus,” 26–32.

Hannah Feldman and Akram Zaatari, “Mining War: Fragments from a Conversation Already Passed,” Art Journal 66, no. 2 (2007): 50.

Bisar, “Salon al-shabab al-ishrun…dawra dun al-mustawa.”

Bisar, “Salon al-shabab al-ishrun…dawra dun al-mustawa;” “Salon al-shabab al-‘ishrun bayn al-tajdid wal-taqti‛a.”

Igor Zabel, “We and the Others.”

Category

Images of panel discussion courtesy Mona Gamil.