The earthworms take their time; let’s take ours.

On Recovery and Anticipation

For any calendrical rite to be what it is, the moments before and after it can only make sense in terms of anticipation and recovery. In the case of events characterized by repetitive cyclical periodicity, recovery is always also anticipation, and the moment after the event is also the moment before the event.

An event is a plea against the equivalence of all moments vis-à-vis each other; it insists that, in a given space, a pre-selected duration has a greater significance than all other moments, save its own future echoes and its subsequent editions. However, each event’s plea against time stands compromised by every other event’s iteration of the same plea.

Competing claims on time produce sporadic peaks of attention, but when the same claims are seen in relation to each other, they flatten into a series of points on the same plane.

But what of the moment—or perhaps we should say the momentum—of the event itself? What happens to time during an event?

On Simultaneity

Contemporaneity, the sensation of being in a time together, is an ancient enigma of a feeling. It is the tug we feel when our times pull at us. But sometimes one has the sense of a paradoxically asynchronous contemporaneity—the strange tug of more than one time and place. Often, an event may feature the simultaneous iteration of many processes. In such an instance, each process will bring to the surface of attention the imprint of its own particular time.

There may be many claims to contemporaneity emerging from different locations, cultures, and experiences—and each claim may also include dormant, barely discernible, and hibernating strands that can by their mere presence influence the tempo and pace of active processes. These strands may not occupy significant cognitive space, and still cast shadows; they are not necessarily limited by location, and may rather be present as tendencies and nascent energies that cut across cultures and geography to generate an “atmosphere” or an “ambience” rather than a concrete reality; regardless of their own ephemerality, they may still be quite influential in an understated or otherwise inarticulate way. In fact, their presence may occasionally be more critical in terms of the shaping of the contours of contemporaneity than other features that are more indexible and articulated. The shadow of these ambiguities makes it difficult—and in some ways unnecessary—to construct a hierarchy amongst different claims to contemporaneity. The ambiguities shade the surface of contemporaneity (taken as a whole) in a manner that is subtle yet conducive to the perception of depth and volume.

A keen awareness of contemporaneity cannot but dissolve the illusion that some things, people, places, and practices are more “now” than others. Seen thus, contemporaneity provokes a sense of the simultaneity of different modes of living and doing things without a prior commitment to any one as being necessarily more true to our times. Any attempt to design structures, whether permanent or provisional, that might express or contain contemporaneity would be incomplete if it were not (also) attentive to realities that are not explicit or manifest. An openness and generosity towards realities that may be, or seem to be, in hibernation, dormant, or still in formation, can only help such structures to be more pertinent and reflective.

On Multiplicity

For decades, the telephony infrastructure in India was beset by chronic underperformance and shortages. For as long as a fixed landline infrastructure wholly owned and operated by a single agency defined what telephony was, it could take up to seven years to get a simple telephone connection, even in a metropolitan center. It took even longer in villages and small towns. Within a few years following the introduction of mobile telephony, India attained one of the highest densities of mobile telephone usage in the world, and has seen an exponential growth in rural telephone use. Today, India has one of the most dynamic cultures of mobile telephone usage in the world.

What kind of realities would suddenly surface if we were to extend this analogy of the transformation from a sluggish monopoly to a dynamic multiplicity to the sphere of the institutional life of contemporary art? If the museum and the large cultural institution were to contemporary art what the fixed landline telephony infrastructure was to telecommunication, what might be the equivalent of mobile telephony? If that equivalent phenomenon were to surface, how might the landscape of contemporary art and culture be transformed in places currently suffering from an infrastructural lag between themselves and the global metropolitan centers of contemporary art? What might such a transformation do to our understanding of contemporary art, and of contemporaneity itself?

How can the paucity or dereliction of museums and large art institutions, of spectacular events and festivals in some parts of the world, be seen not as a liability but as an asset? What might be necessary to make this a condition not of barrenness, but of fertility?

The cultivation of such terrain requires the patient ploughing of cultural soil, through multiple acts of turning, burrowing, tunneling, and composting. It requires, not the action of a single combine harvester but the agency of a million earthworms, doing what earthworms do best, in their own time.

For example, can we imagine a biennale stretching to become something that happens across two years rather than something that happens once every two years?

On Syncopation

Space is finite, but time is porous. Only a given number of people and processes can occupy a space at a given moment, but any number of things can happen over time. A process built on the principle of dispersal over time can allow for the unfolding of many more possibilities than one that seeks to cram as many things as possible into a single space.

The Ottoman solution to the seemingly intractable conflicts over the control of different Christian churches built upon the site of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem evolved into a carefully calibrated arrangement in which the very important element of co-inhabiting time was deeply embedded. Because no single denomination could lay full claim to the space of the church, in order to ensure that no one had a monopoly, each was persuaded to agree to share time, such that no one felt completely left out of the running and maintenance of the site. While this was by no means a perfect solution, and conflicts (especially over procedure and precedence) could not always be avoided, it did go a long way towards settling endless disputes over ownership and control.

To co-inhabit a time is not to establish orders of precedence or chronology, but to create structures and processes by which different rhythms of being and doing can act responsively towards each other.

A musical analogy may be fruitful here. When two different instruments play to two different rhythms within the frame of the same composition, the two rhythmic cycles influence each other’s sonic presence in time without necessarily entering into conflict with each other. The phenomenon of musical syncopation expresses what this mutual co-inhabitation is all about.

On Biennales and Time

The visitor to a biennale finds him- or herself surrounded not only by an array of exhibits occupying positions within the space of the exhibition, but also by a set of loci within the global contemporary art system’s emerging grid of circulation and meaning. Each biennale is at present an adjunct, a neighbor, a response, or a rival to every other biennale. Objects, exhibits, and artists that momentarily inhabit a biennale also circulate within networks of affinity, confirmation, and competition that are much more expansive than the boundaries of the biennale event itself. Thus a viewer is obliged to slice up his or her attention not only in order to take in the multitude of objects within a single exhibition but also to accommodate an awareness of how that multitude of objects and artists circulates between and across different exhibitions, different biennales. The ideas of trends, movements, singularities, and discoveries that biennales so efficiently signpost would not make sense were it not for the implicit comparative register that underpins the biennale system.

This slicing-up of attention—attention to different layers of simultaneous and overlapping, or immediately serialized, circuits of exhibition—leads to a rapid acceleration in the experience of artworks. The momentum of the experience of contemporary art then becomes a matter of being borne aloft by the velocities of the strong currents that propel exhibitions and/or artists from one show to another.

We have less time to experience what we encounter, even as we encounter much more of what we experience.

The attrition that accompanies the rush and exhaustion of attending a biennale provokes a rhetorical dismissal of the proliferation of biennales. The problem is not the arithmetical increase in biennales, but rather the temporal experience of compression within and between exhibitions that creates the bi-polarity of glut and famine within the attention economy of the global contemporary art system.

Towards a Biennale in Slow Motion

What would happen if a biennale were to forsake its claim to attention as a single event, and instead stretch across time—break its banks, overflow, demand a different, non-rivalrous order of consideration?

A biennale in rehearsal, a biennale in recess, a biennale at work, a biennale working overtime, a biennale taking stock, a biennale in waiting—the tempi of all these processes can add up to a biennale speculatively seen as one “in slow motion.” The criteria for the evaluation of such a biennale would not be determined by the pace of other events, other biennales, but by the rhythms of life in the place where it is located.

In fact, location, place, the very “where” of a slow-motion biennale, can remain an open question. A biennale that sees itself as primarily spanning time need not, in the end, confine itself to a fixed place. A stretched-out biennale, like any image seen in slow motion, opens itself up like a loop that can be read across a range of possibilities. The amplification of detail in the rendition of objects and humans in a slow-motion image can cause them to appear to move in more than one direction.

Or, seen another way, the trajectories of moves made during such a biennale could unfold in unforeseen and unpredictable directions, causing processes to grow, mutate, fall back on themselves, hibernate when need be, change course, and proliferate. Such oscillations and transformations can happen without the anxiety of having to rush to premature conclusions within a slow-motion biennale’s expanded field of attention.

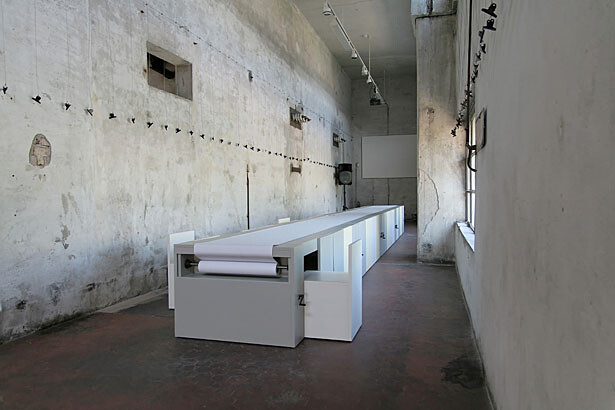

Curatorially, a slow-motion biennale is a platform for the development—rather than the statement—of an argument. Works from the artists’ atelier will not necessarily arrive at such a biennale fully formed, and may leave the biennale in a more mature state than when they first reached it.

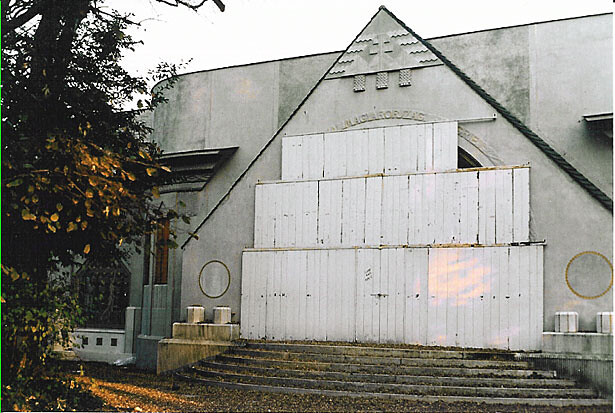

A slow-motion biennale need not stage a high-intensity occupancy of infrastructure. Being accretive, it can expand and grow at its own pace, making moves across a flexible network of available (possibly dormant) buildings and spaces over the full span of two years rather than enact a demanding and intense short-term occupation of a single facility that would otherwise lie fallow until its next episode of high-intensity occupation.

Those responsible for the architectonics of a slow-motion biennale would then have to pay as much attention to the question of what to do within the extended span of occupancy of a given space as they would to spatial and architectural questions. The beginning, unfurling, and ending of processes—their rhetoric and their quality—would then be as important for the architect of such a biennale as questions of volume and scale in a building.

The space for art, art-making, and talking about art in any such endeavor would be pried open, unstable, untethered to institutional guarantees, and in some ways even rendered insecure. If given time, however, such an initiative may turn the top-soil of culture, making it porous and fertile in much the same way as earthworms have ploughed the earth for millennia. Here, in “slow-motion” processes such as the subterranean dance of the earthworms, lie the foundations for the fertility of the future.

The earthworms take their time; let’s take ours.