The title of this text is a hybrid of two existing titles. “Architecture without Architects” was the name of an influential exhibition by the architect Bernard Rudofsky at the MoMA in 1964; “Housing: An Anarchist Approach” was the name of a famous book by the English architect and anarchist Colin Ward in which the author proclaims the rights and productivity of self-built housing and squatting in postwar Europe. Whereas the latter’s collection of essays discussed specific cases of European and Latin American squatter movements from the 1940s to the 1970s, Rudofsky’s exhibition presented photographs of local vernacular architecture from all over the world, with the claim that architects should learn from premodern architectural forms. Both of these perspectives identify a condition that emerged during decolonization, in which a massive crack appeared in the modernist movement and its vision of top-down planning. But they were also two very different interpretations of the simple fact that, throughout the ages and around the world, architecture has been produced without the intervention of planners or architects. Whereas Rudofsky’s approach suggested an aesthetical and methodological shift, Colin Ward’s was a political reading of spatial self-expressions that might offer new methodologies and an alternative understanding of society. In my article, after more than thirty years of debates about High Modernism, I will try to bring into play a third way of thinking that attempts to connect the question of design with that of the political, from the perspective of a globalized world. These ideas have been informed by many conversations, much research, and invitations to Egypt, Morocco, and Israel. I would like to thank everyone who was involved in these discussions: Nezar AlSayyad, Kader Attia, Tom Avermaete, Dana Diminescu, Noam Dvir, Zvi Efrat, Sherif El-Azma, Monique Eleb, Jesko Fezer, Tom Holert, Shahira Issa, Serhat Karakayali, Abderrahim Kassou, Brian Kuan Wood, Andreas Müller, Omar Nagati, Françoise Navez Bouchanine, Horia Serhane, Katja Reichard, Peter Spillmann, and Daniel Weiss.

A Colonial Global Modernity

“Travelling between any two cities in the world, passing through airports along ring roads and into business districts or tourist hotels, seems, at least in part, always to be a return home. In the main this is because modern architecture is a global phenomenon and what contains and helps to define or frame our experiences are usually buildings of familiar appearance,” says the English art historian Mark Crinson in the introduction to his book Modern Architecture and the End of Empire. He argues here that this global similarity and formal analogy concerns more than just modern architecture: “More specifically it is modernist architecture: that embrace of technology, that imagined escape from history, that desire for transparency and health, that litany of abstract forms …”1 For Crinson, this universal formal language, with its norms and forms, has created the global language and appearance sufficient to suggest a common trajectory shared by globalized cities today.

At first glance, modernist architecture and urban planning appear to have little in common with New Urbanism’s gated communities and upper-class boulevards, built far away from the Global City center and the informal settlements growing up on its outskirts. The differences become even more obvious as we learn that modernist discourse on urban planning was not meant to serve only the new urban elites; on the contrary, modernist architecture and urban utopias were designed to be the ultimate urban fabric, creating and realizing entirely new societies and modern citizens. The function of modernist architecture as both symbol and organizational model for the “new modern man” in Europe and America, as well as in the colonies, must be highlighted here. Housing and urban planning projects symbolized a new society, representing a modern, industrialized way of living, working, and consuming. Moreover, urban planning as such was an invention of Euro-American modernity, having emerged towards the end of the eighteenth century, in times of aggressive colonial expansion and the advancement of a new world order. The spirit of social reform, based on new forms of industrial manufacturing and consumption, was translated into the first master plans for housing developments, and these concepts for urban planning became schema that were used strategically for very different social groups, having in common only their use as a tool for governing life and the living being. As spatial organization and urban planning served to strategically control and mobilize a population, and appropriate its territory, so did it also claim to shelter this same population.

Some years ago, researchers became aware that in the period of modernist ascendancy, and in particular during what came to be known as High Modernism, colonial territories became laboratories for European avant-garde architects and urban planners to realize many of their experiments. The discourse surrounding colonial New Town planning was, upon its emergence, immediately recognized internationally, documented in magazines, congresses, and exhibitions. Concepts and practices traveled not only from Europe and America to the global South, but also moved in the opposite direction. In essence, Modern city planning has always been bound to colonialism and imperialism—many large-scale technical developments were even tested and realized on colonial ground. Colonial modernity not only created global political and economic structures, pressing for the adoption of the nation state and capitalist forms of production, accompanied by oppression, exploitation, and the systematization of racial divisions, but it also produced, as Crinson remarks, the aesthetical and infrastructural basis for a globalized world, for the global modernity we live in, as the post-colonial historian Arif Dirlik has it.2

The travel experience in a globalized world, formed by a colonial modernity, is today additionally structured by a global elite and its flows of capital, its production sites, its aesthetics, infrastructures, and urban lifestyles. Cities are influenced by multiple simultaneous trajectories—the new geometries of a network society, as Manuel Castells describes them—drawn by the telos of globalization.3 Global Cities today seem to be governed and structured more by privatized initiatives than they were in modernist and Fordist times, in which the nation-state was the central actor in both Europe and America and in the colonized South. Many studies, books, and exhibitions in the last decades have focused on global flows of capital and transnational enterprise, as well as on the informal network economies and migrations that accompany them. In these cases, the activities of non-governmental organizations and enterprises seem to be the key players in determining how urban landscapes are created and used in very particular ways.

Beyond the almost forgotten colonial modernity that Mark Crinson brought back into the debate on Global Cities, there are certainly many trajectories and actors other than new global or neocolonial powers shaping the urban fabric today. In these Global Cities, an increasing number of improvised practices have become key forces shaping the urban landscape by creating new possibilities and realities for making life a bit easier for the individual as well as for the community. In one example among many, one finds people improvising pathways that cut through emblems of global modernity—crisscrossing highways, districts, and gated communities, re-partitioning segregating infrastructure by asserting a new layer of functionality. The same is true for the self-builders who, for practical reasons, occupy land just beyond the walls of New Urbanism’s gated communities to construct improvised huts.

The French sociologist Alain Tarrius goes a step further, arguing in his latest book La romentée des Sud that, contrary to the assumption that the South is structured by flows of global capital, one instead finds its local and transnational economies impacted mainly by a growing number of informal and migratory practices.4 By taking into account the informal activities of small-scale economies and the flows of capital linked to transnational migration, Tarrius arrives at the conclusion that a comparison of the economic output of the formal and informal sectors of the North and the South does not present as stark an asymmetry as the West has liked to imagine. Nevertheless, while perceptions have shifted, allowing us to look beyond the grand narratives of Western globalization theories, it remains important to acknowledge how North-South relationships are still hierarchically structured.

Various localities, social groups, and local actors have each perceived the aesthetic and infrastructural basis of colonial modernity in their own way; most significantly, this modernity has been appropriated and used against its aforementioned original intentions. The appropriation of colonial infrastructure’s leftovers—its existing buildings, public spaces, and territories—articulate personal needs and practices that improve the circumstances of contemporary inhabitants. If one takes these various strategies into account, one finds that they, too, assume the shape of universal patterns, spanning the globe. They follow migration patterns and transnational ways of living, as improving conditions within precarious economic environments are linked to the transnational flows of money sent from relatives working and living abroad, forming global patterns that concern not only mobility but new approaches and contributions to existing city structures as well.

As the users of the leftovers of colonial modern infrastructures and landscapes, these dwellers and self-builders appropriate existing buildings, public spaces, and territories to articulate personal needs and relieve the precariousness of their situation. If we look more closely at the junctions and coordinate systems of mobility and circulation reflected by these small-scale improvements, what we find are not established and settled societies, but dynamic and interconnected transnational spaces created by migration. These migrations, however, gain their legitimacy more from the migrations that preceded them than from the logic of arriving at and occupying new territory. Migrants have now settled many areas beyond the spaces of urban majorities, informed and encouraged by the never-ending movements of migration itself. Yet those who move to work abroad are not the poorest people in a society, but usually come from a family background in which an investment has had to be made in a shop, a house, education, and so on. Inhabitants’ everyday practices of coping with their circumstances—their means of appropriating existing environments or territories as well as the transnational reality of migratory societies—respond to existing conditions and circumstances stemming from the colonial modern past as well as the global modern present. These practices are therefore extremely contemporary, and almost anarchistic in nature.

The Vernacular as Didactic Model

The tension between the formal and the informal city, between architecture by architects and architecture without architects, has existed since the very beginning of the modern urbanization project. Prompted by capitalist class-making and the influx of rural migration to cities, large housing programs and informal housing increasingly grew up near the city’s borders—the city essentially began to build itself. The trajectories of this tension between the formal and the informal city were major attractors for the emergence of the modernist movement towards the end of the nineteenth century as well. Their studies of vernacular architecture in the Mediterranean and its aesthetics, functions, and structures were partially synthesized into the most modern form of new industrialized building types. Though they were hybrid translations, modernist houses and settlements, with their whitewashed walls, created the idea of a pure form and a hierarchy between the modern and the premodern. By asserting a temporal rupture between the contemporary and the traditional, modernism embraced the possibilities of industrialization and standardized forms. This technocratic and formal approach experienced a deep crisis in the 1950s when the next generation took the self-built environments of hut settlements on colonial ground into account in designing processes and models for urban planning.

For a number of years, I have been interested in the deep crisis in High-Modernist thinking that came about in the era of decolonization, prompting me to begin an investigation into the housing developments that were built under colonial rule, mainly in Casablanca in the 1950s on the outskirts of the European city. This article will offer some open-ended thoughts relating to my research. This paradigm shift in the postwar years marked a great paradox, as colonial modernity was, and is, an articulation of the ultimate ability to plan a society. As previously mentioned, colonial modernity also became a testing ground for new discourses around modernization and for the large housing programs that were installed throughout Europe and America and the colonies after the war to create a global consumer society. But at the same time as global decolonization was taking place, this ability to plan was placed into question by a younger generation in the West, who were interested in the everyday, the popular, and the discovery of the ordinary celebrated by the so-called “found” aesthetics that encouraged a new relationship to the constructed environment as it is used and visually perceived by photographs and anthropological studies.5

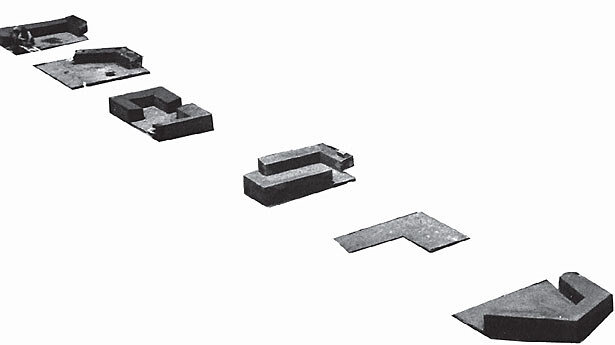

A result of this shift in perspective was the dispute at the ninth CIAM (Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne) meeting in Aix-en-Provence in the summer of 1953, in which a team of young architects (who later formed the group “Team 10,” when they were charged with organizing the tenth congress) presented new ideas on urbanism and the function of architecture that were highly critical of the functional separation between housing, work, leisure, and transportation in urban planning. In calling for an amendment to the 1933 Athens Charter developed at the first CIAM meeting, the group wanted to call attention to the interconnectedness of housing, street, district, and city, and the meeting ended in conflicts with the congress’ older generation of founding members such as Le Corbusier, Gropius, and Gideon. The context for this dispute were three visual urban studies (so-called “grids”): the “GAMMA Grid” generated by the Service de L’Urbanisme from Casablanca (which included the young George Candilis, Vladimir Bodiansky, and Shadrach Woods), a study of an Algerian shantytown in the “Mahieddine Grid” by Roland Simounet and others; and the “Urban Re-Identification Grid” by Alison and Peter Smithson, a study of how playing children used the street in East London’s working class and colonial migrant district of Bethnal Green. Two of these studies were investigations of the self-built shantytowns that grew up on the outskirts of the French colonial towns of Casablanca and Algiers. All three studies resulted in discussions concerning how the CIAM IX congress itself marked a worldwide shift in approaches to postwar modern building for its presentation of self-built environments as models for understanding the interrelation of public and the private spheres in relation to a new concept called “Habitat.” Discussions stemming from the studies of working class districts and shantytowns led to a generational conflict that marked the dissolution of CIAM as an international organization of the modernist movement.6

My interest in this crisis is twofold, and provokes many questions that are still relevant today. First off, two architects from the GAMMA group, Georges Candilis and Shadrach Woods, later leading Team 10 members, were already able to present a completely planned and realized building that they had constructed as an experimental high-rise structure for incoming Moroccan workers alongside the shantytowns in Casablanca—they had transferred their analysis of hut settlements directly onto a modernist architectural project. In the framework of Casablanca’s extension plan, they built two experimental housing blocks—the Cité Verticale—that synthesized their studies of the reality of the Bidonville with the modernist approach to planning. The result was a design that integrated the Bidonvilles’ everyday vernacular practices, local climatic conditions, and a modernist idea of educating people for a better future. On a formal level, the buildings can be seen as a type of local traditional building—the patio house—translated into a stacked block of apartments. And yet, the basic capacity for young architects to fully realize a whole settlement was fundamentally bound to the circumstances of colonial occupation, and this was not questioned by the new generation. Still, the building model and shantytown study had a lasting influence on a younger generation of architects, who witnessed modernism appearing to adapt to local climatic and “cultural” conditions and deviating slightly from its universalist path.7

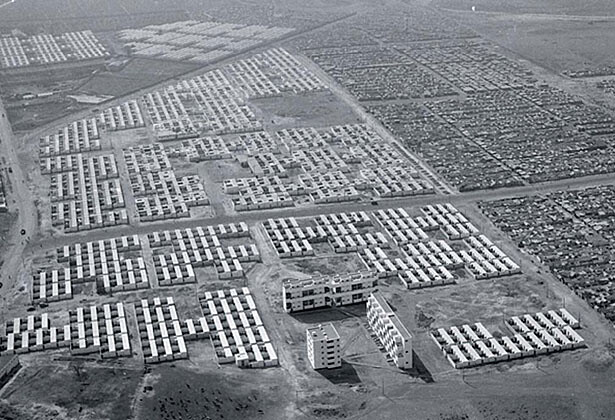

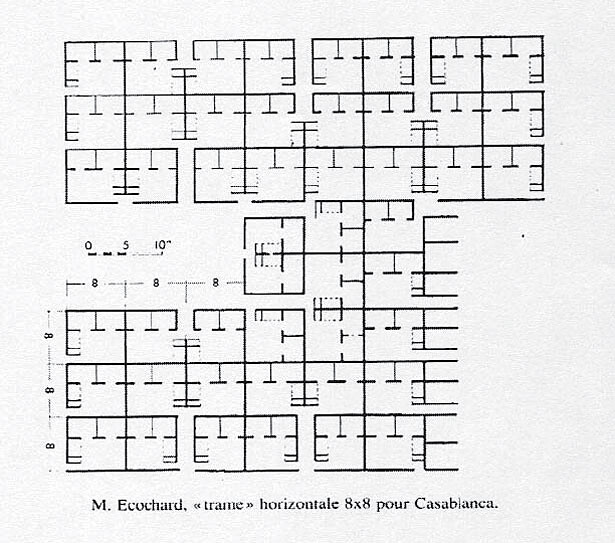

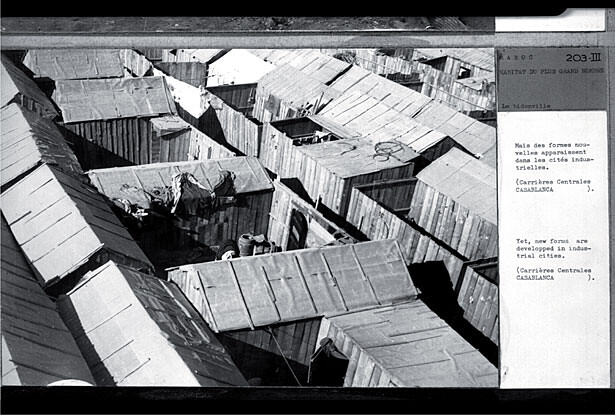

The new housing programs—of which the Cité Verticale was only one among many—were a first attempt by the French protectorate to build modern settlements for the colonized and not for the colonizers. In Morocco and Algeria, these programs were a response to the growing influx of migrants from the countryside into the colonial city after World War II, for whom the French protectorate built fenced settlements far from the colonial city centers. Within these, Moroccan settlers began building informal huts, which were then named after the materials used to build them, such as in the case of “Bidonville” (Tin Can City). The shantytowns that emerged from this limited access to the formal city centers became the subject of the “Service de l’Urbanisme” project implemented in the last decade of French rule in Morocco and led by Michel Ecochard, the director of Casablanca’s urban planning office. The strategy of the protectorate from the late 1940s on was to build enormous numbers of housing estates in the framework of a large-scale extension plan of the city, one of the largest planning operations of the time for the new sub-proletarian workforce. The strategies of the Service de L’Urbanisme varied from the reordering of the Bidonville (restructuration) to temporary rehousing (relogement) and finally to the creation of new housing estates (habitations à loyer modéré) based on the standard Ecochard grid of small, quickly built single-floor patio houses. These low-rise settlements were originally developed to contain and govern the growing number of inhabitants living in the shantytowns and working under horrible conditions in the nearby phosphate factories; as urban strategies they were from the outset located in the field of tension between the emancipatory aims of improving inhabitants’ everyday lives and the search for appropriate governing tools that complied with these intentions. In 1952, an important march organized by the Istiqlal Party, the national liberation movement, and other anti-colonial forces took place in the Bidonvilles of Carrière Centrale, and was brutally suppressed by the French rulers. As a result, the construction of the new housing plan took place in the midst of military actions with tanks and heavily armed troops, arrests and killing. Though it must have been virtually impossible not to recognize the conflict, the optimistic young French planners seemed hardly disturbed by the conditions surrounding their work.

Moreover, many ambiguous attitudes emerged on the part of the colonial rulers towards the existing territory and its inhabitants. While the Ecochard plan applied notions of “culturally specific” dwelling, taking—in their interpretation—local practices as a point of departure in developing a variety of dwelling typologies for different categories of inhabitants, these categories were still confined to existing definitions of cultural and racial difference. However, it was only under colonial rule that they were reinforced and converted to technologies of governance. While the new housing complexes of Carrière centrale, El Hank, Sidi Othman, and others were divided both racially and religiously into developments for Muslims, Jews, and Europeans, the estates for “Muslims” were built farther away from the colonial European city center, on the edge of an empty intermediate zone known as the “Zone Sanitaire.” This striking spatial segregation was a legacy of the colonial apartheid regime in which Moroccans were forbidden to enter the protectorate city unless they were employed as domestic servants in European households, and likewise constituted a strategic measure, facilitating military operations against possible resistance struggles.

The shared concepts and singular works of Team 10 have been widely discussed and researched by architecture historians lately, as a young generation of architects searches for an adaptable modernist language that goes beyond the recent elitism of star architecture. But many recent re-evaluations have been blind to the context and conditions to which the Team 10 ideas were connected, mainly as studies on vernacular architecture and large-scale New Town planning in French colonies. Moreover, many authors have claimed that Team 10 architects in Morocco were the only ones to have considered the possibility of appropriating already-built structures in their plans. Looking at the floor plans, however, one merely finds the inclusion of a balcony as a patio-like space and various ways of connecting multiple apartments to a communal area, concepts still based on a European conception of a nuclear family and hardly an incorporation of the needs and ways of living of the people for whom it was built, representing a hybrid of colonial modernity and its so-called “culturally specific” conceptions.

For European architects, the hut settlements and Bidonvilles were merely the spatial expression of a rural or culturally specific tradition of unplanned self-organization, a natural consequence of the disorganized structure of the new suburban situation that demanded their intervention and ordering principles; it was inconceivable that shantytowns might have existed only because the protectorate forbade people from participating in the colonial city itself. Moreover, the specific urban—and already modern—character of the self-built environment that was already a means of coping with modern city life (as well as colonial subordination) was not taken into consideration by Western planners, and any sympathies they might have had for the liberation movement have never been expressed in their writings. On the contrary, the architects positioned themselves as representing the needs of the local people while barring the same population from participating in their decision-making processes. For them, learning from the inhabitants was only a matter of adjusting their planning and architecture according to ethnological findings. Their concept of observing everyday dwelling related uncritically to already existing ethnological and anthropological studies and Orientalist narratives of African space, which included perspectives similar to those used to study the working class in Europe. In addition, while new concepts of postwar architectural modernism strongly related to the everyday practices of population groups that had become mobile, they were on the other hand used to regulate and control, employing the planning instrument of an architecture for the “greatest number.” Hence, improvised dwelling practices (which, like migration itself, are a type of survival strategy) were only transferred into new planning concepts for larger architectural and urban environments such as the satellite city Toulouse-Le Mirail, which Candilis, Josic, and Woods built after French decolonization. Planning not just one settlement, but a completely new town and its social, communication, and traffic systems, Toulouse-Le Mirail was planned to such an extreme that it was as if the experience of the anti-colonial movement had been completely forgotten. To this day, architects and architectural theorists have yet to fully question the colonial and postcolonial motives embedded within their own planning discourses. The ethnographic regime that emerged from the postwar modernists’ early studies of the vernacular, the self-built, and squatter movements in the colonies was merely confirmed when the movement used an anthropological framework as a device for architectural planning. Simultaneously—and this is essential—the struggles of the anti-colonial liberation movements have been erased from that history, and as a result the postcolonial subject—as the subject of another modernity—is still in the making.

The didactic model of vernacular and self-built architecture—which remains influential even today for Rem Koolhaas and others—has to be critically examined in the context of colonial and global modernity. The “Learning from … ” methodology needs to be contextualized against its ambiguous and asymmetrical postcolonial histories. With this and many other relevant critiques of Euro-American modernism in mind, it becomes important to acknowledge the impossibility of projecting any new utopias from the aesthetic regimes of planned worlds, the universal abilities of the human subject, or the “creativity of the poor,” studied by the modern sciences only to improve Western design practices.

Negotiating Modernity—Making the Present

When visiting the famous settlements built by George Candilis and Shadrach Woods in Casablanca for the first time some years ago, I encountered the same difficulty reported by many other visitors before me: one can hardly find (or recognize) the buildings or the neighborhoods anymore. This was partly due to the fact that the banlieues still had yet to be included in Casablanca’s city map, but also because their inhabitants had appropriated the buildings to such an extent that they were rendered nearly unrecognizable. The buildings had not been whitewashed and Corbusier–colored for some time, repainted instead in light yellow and bonbon-rose. The famous balconies of the Cité Verticale—published in so many international magazines and books—had been closed off to create spare rooms, and on some of the flat roofs people had improvised terraces similar to the vision of the Unité d’habitation. On the entrance level new doors had been introduced, and little front gardens with shade trees and flowers had been planted. In one of the ground-floor apartments, a carpenter built hand-made modern kitchen furniture, while plaster ornaments for the interiors were sold in another. I managed to speak with many of the people living in this exceptional building, and found that, like those who lived in the Cité Verticale or the Sidi Othman, built by the Swiss architects Hentsch and Studer, they were well informed of the buildings’ exceptional status and almost proud to live there. Likewise, they took pains to distinguish their neighborhoods from the existing Bidonvilles around them, however similar they were in scale and function. Most of the inhabitants had lived there since the buildings were erected, or were born there. Though the symbolic function of the high-rise model buildings had done its part to create the “new modern man,” the inhabitants remained dependent on the income of one or two relatives working abroad in order to improve and to appropriate the buildings. Several people in the postwar-era settlements, young and old, spoke of having members of the family in Europe or the US who would return to Morocco in the summer. Some of these relatives even lived in the banlieues around Paris, built just a few years after the high-rise buildings in Morocco.

But the disorientation experienced by a first-time visitor to the outskirts of the town is not only due to the new additions and improvements by inhabitants to the high-rise settlements, but also—and to a greater degree—to the urban fabric surrounding these famous buildings, which remains that of the monstrous industrialized housing plan created by Michel Ecochard. The so-called “carpet settlements,” the standard 1950s grid, provided the basis for what was to become the major urban fabric of today’s Casablanca. From Moroccan independence up to the early 1980s, this model was continuously built up by the urban planning offices of the Kingdom. The structures of these carpet settlements were implemented in other North African countries as well, and even in an adapted form in Israel. One can understand them as a North-African colonial base-model structure, and they ultimately provided much more viable foundations for city-building than the exceptional high-rises built in their midst. The Ecochard grid created the universal industrialized language for rapidly built workers’ homes and large territorial expansions. In Morocco they were adapted by the postcolonial powers to house the new proletarian classes, which had not experienced any fundamental improvement in social status after the French protectorate left the country in 1956. Thus the trajectories of colonial modernity can still be traced in all spheres of life today.

Nevertheless, when visiting Casablanca, it is striking to find not only that the Ecochard Grid played such a significant role in forming the urban fabric, but also to see how their aforementioned disciplinary and highly segregating character has almost disappeared. This shift did not emerge through any process of democratization on the part of the government, but rather through the various means of appropriation performed by the inhabitants themselves. Perhaps even more remarkable, the single-floor mass-built modernist Patio Houses, intended to facilitate the control of Moroccan workers, have been altered so significantly that one can no longer distinguish the original base structure. The builders simply used the French planners’ original design as a base structure upon which to construct three or four floors of apartments. This is by no means an isolated example: when visiting Casablanca, one finds that nearly all of the buildings in its outskirts have been appropriated in a similar way.

When reflecting on these carpet settlements and their application as basic infrastructures, one finds that in spite of their problematic intentions, they still prove useful for people—and this could be much more extensively studied. A new approach to planning would therefore begin with a reflection upon how existing needs of inhabitants have been expressed in the appropriation of these infrastructures, providing insight into the possibility of improving the existing world.

What one can “learn” from the actual uses of the colonial modern “heritage” concerns its manifold adaptations to circumstances after decolonization, to regulate people surely, but also as a basis for the self-expression of those that it sought to govern. Though the housing programs did take certain specific local conditions into account when they were conceived, these conditions turned out to be much more complex after decolonization than previously thought. The argument that the Team 10 buildings were the only ones to have accommodated the possibility of appropriation in their design grows weaker when one observes how a modernist city such as Casablanca has been used and changed by its citizens. The many ways of appropriating space and architecture by the people led to the assumption that both colonialism and the postcolonial government never managed to assume complete power over the population, and that the level of craftsmanship within the population remains very high. When I asked the man who guided us through Hentsch and Studer’s Sidi Othman Building about how public spaces, architecture, and interiors have been so thoroughly appropriated by the people, he responded that, “We are all engineers, we are all architects. If we have a basic structure or land, we just start to build.” This surely marks a relationship to one’s environment that is almost forgotten in Western societies: that we are all architects.

The urban fabric of many other southern Mediterranean cities is filled with so-called “spontaneous” settlements, in addition to the hut settlements. Already in the 1950s these self-built settlements were the locus of the first encounters and negotiations with the modern city for a number of people moving to the city from rural areas. Horia Serhane, an urban theorist from Morocco, has stated that people in the hut settlements learned about building practices in the city quarter, the Medina, which was already a multiethnic town structure before the French occupied the country (It was subsequently museumized by colonists and tourists from Europe.) The concept of the Medina house is that of a growing house, a house that is built according to the needs and developments of a family or community. This strategy was then applied by newcomers to the self-built hut settlements of the Bidonvilles, and this is still the case today. Those huts not destroyed by bulldozers or owned by slumlords might—and often do—grow into brick homes over time, and into stable city neighborhoods.

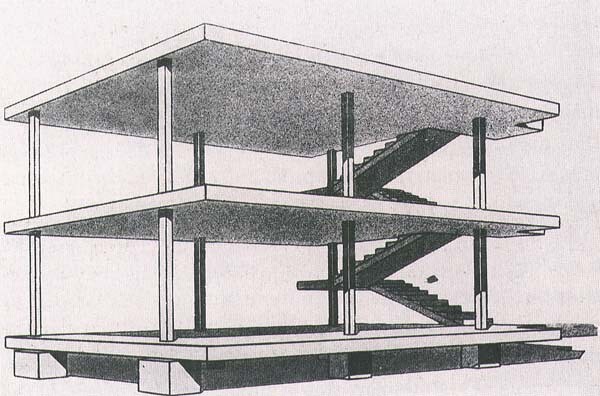

If one takes a broader look at the many self-built houses south of the Mediterranean that use the almost universal standard of a concrete-steel grid of pillars, one finds large swathes of growing cities created with these elementary structures. This simple grid has become standard for the growing building practices found in hut settlements, in the Medina, as well as in the previously discussed “spontaneous” settlements. People begin by building a first floor with this simple concrete-steel grid and leave the structure open on the roof to retain the possibility for further building—when the finances are there, the family grows, whenever it becomes possible or necessary. But this basic structure is virtually a replica of the Maison Dom-ino developed by Le Corbusier in 1914–15, which used simple reinforced concrete pillars as part of an industrialized building process influenced by the mass production of goods. Corbusier developed the Maison Dom-ino as a basic building prototype for mass-produced housing with freestanding pillars and rigid floors. As we can see, his ideas became not only a foundation for the modernist approach to architecture in general, but also for self-builders in the global South. Whether or not these are the best solutions for responding to weather and temperature remains an open question, but in terms of usable hardware, these concepts have become a form of common property, a part of the public domain.

A third way of thinking about architecture without architects might begin by reflecting on the trajectories of colonial and global modernity, and how people can make use of them today. The contact zone, which, as James Clifford showed, was affected by concepts and practices of modernity, colonialism, and migration, is reformulated and adapted by minor daily practices, small in scale but globally massive in number and impact. This shift in perspective might suggest possibilities for rethinking certain political concepts. On the one hand, the new boundaries created by global modernity and its politics of exclusion attempt to regulate mobility and circulation between the South and the North in a way that can be compared with the restriction of access to the colonial city. Meanwhile, however, the practices of those who are dealing with these limitations by crossing and appropriating both its border regimes and its pre-fabricated urban landscapes are creating another post-national contemporary reality that assumes another logic altogether.

These are not signs of pessimism but rather of a new political demand, as well as a broader understanding of the concepts of citizenship and participation. Moreover, urban infrastructures that are built, used, squatted, and claimed by the people themselves are almost nonexistent in Western societies, which themselves claim to offer more possibilities for liberal forms of living than non-Western societies. From the point of view of these investigations into daily practices of appropriation and self-building in the South, these concepts need to be rethought as well, as the central question concerns whose freedom we are talking about, and from what perspective. In both colonial and postcolonial situations where modernity arose and transformed itself, it was usually the result of conflict-ridden and contradictory appropriations and reinterpretations. The tensions within the modern project still remain to be resolved, because too little attention has been given to the roles played by the decisive actors in transforming modernity. The different ways in which the various spheres of modernity—socio-economic, artistic, political, and so forth—are interrelated have been, and still are, regulated by a regime that shifts through negotiation, conflict, and struggle.

To close this article, I would like to return to my investigations of the Cité Verticale. It was only a few weeks ago that I managed to put down my thoughts on a structure created by Candilis and Woods that partially went beyond the above-mentioned conceptions of High Modernism and its crisis. This structure is actually a very abstract form that was placed outside the Cité Verticale, and it seemed to have a kind of non-utilitarian, almost contingent (non)function. As loose additions to the constructed buildings, these objects might be understood as an early experiment by young architects to create extensions from the home into public space. Their form almost reminds one of minimal sculptures, but surely they were intended to be functional objects. However, their intended use can no longer be determined. Today, gardens, new door entrances, and workshops have used these extensions as possible ground structures. The objects might therefore be the only expression one can find on the part of the architects that they accepted, on local ground, that they were no longer the masters of the plan or the authors of the needs of others—that the emerging postcolonial society they witnessed beyond their construction site would soon take over (the French departed and Morocco became independent only three years after the buildings were erected). They suggest a disclosure on the part of the modernist architects that they in fact had no idea how to react to the self-articulations of the subaltern, which previously had no voice. In this almost unnoticed projection into the public sphere, they tried to react to something useful and useless at the same time, as they had no idea where this emerging social process would eventually end. This almost deviant approach to design might have been their way out of the dilemma of having to plan and study the colonized through presumptions and severe misreadings, out of the trap of the colonial powers’ monstrous urban plans. But perhaps they still understood that the most radical form of design emerges when the people begin to represent themselves without mediators and masters. And until now, one finds no writing about these strange objects just outside the settlement. To revaluate and speculate on them became for me a point of departure, and perhaps the basis for a future shift in perspective.

Mark Crinson, Modern Architecture and the End of Empire (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2003), 1.

Arif Dirlik, Global Modernity: Modernity in the Age of Global Capitalism (London: Paradigm Publishers, 2006).

Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000).

Alain Tarrius, La remontée des Sud: Afghans et Marocains en Europe méridionale (La Tour d’Aigues, France: Éditions de l’Aube, 2007).

See for example Claude Lichtenstein and Thomas Schregenberger, eds., As Found: The Discovery of the Ordinary (Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers, 2001); Felicity Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics after Modernism (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007); and many other publications of the last ten years.

See Jos Bosman et al., Team 10: 1953–1981, In Search of a Utopia of the Present (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2005); cf. →.

See Tom Avermaete, Another Modern: The Post-War Architecture and Urbanism of Candilis-Josic-Woods (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2006).

Category

Subject

Many of the ideas expressed in this text culminated in “In the Desert of Modernity: Colonial Planning and After,” an exhibition and accompanying program of events curated by von Osten, which took place from 29 August to 2 November 2008 at the House of World Cultures in Berlin.