“Identity, please!”

In Europe, the past has always been much better than the present. Those who see European identity diluted, its legacy erased—public places smattered with graffiti and covered with advertising, names forgotten, classical languages unlearned, French and German replaced by broken English—are concerned that all that was ever good about Europe may be bound to transform beyond recognition. But their lament, however justifiable, disregards the fact that the meaning of Europe and the values assigned to it are indissolubly bound to practices and processes rather than ideas. The prosaic, the makeshift, and the managerial have come to prevail over supreme beauty and ethics.

There is no denying that the ubiquitous “Euro-” prefix that faithfully continues to promote Europe hardly designates a luxury brand. The enormous economic achievements of the single European currency notwithstanding, it would be difficult to claim that the Euro banknotes, with their drawings of fictitious historical buildings, make a fantastic contribution to contemporary art and design. And probably not too many people appreciate the sobering monument installed in the Luxembourg town of Remerschen to commemorate the 1985 Treaty of Schengen. These are just a few examples; in fact, quite a substantial share of European identity breathes boredom and cheapness, and this situation is not to be attributed to any form of central control or branding, but rather to the simultaneous deployment of market liberalism, good intentions, and managerial protocol.

This article compares a Europe of historical ideas with a Europe of practices. It is the comparison between two brand identities: one historical, highly visible, and very important; the other semi-new (already aging), stealthy (somewhat invisible), and cheap (affordable). This comparison leads to further reflection on the EU’s idea of power (without coercion, of course), its territorial and monetary borders, and the surveillance and protocol used to enforce them. Meanwhile, various social movements have reclaimed resistance and rioting as a means to occupy precisely those historical symbols belonging to Europe’s past.

Rossini was Here

Our story begins in a French banlieue. Fontbarlettes is an unheard-of suburb on the outskirts of the southeastern city of Valence, and it is here that we are suddenly reminded of European heritage.

The cold mistral wind sweeps the concrete slabs and crumbling housing projects of Fontbarlettes as they lie barren among parking lots and treeless, deserted parks. Abstract art made on the assembly line of the public good has been parachuted onto the streets of this forgotten town and left to rust in rain and snow. Tiny balconies, designed to accommodate middle-class desires, have been crammed with dish antennas aimed at faraway satellites. The shopping center is a U-shaped piazza: utilitarian single-story big box structures sheltered under a superficially postmodern roof. The heart of Fontbarlettes is an empty concrete rectangle. All shops including the Lidl supermarket are kept behind vandal-proof metal fences.

Fontbarlettes is European. Not just in the obvious sense that it is situated in Europe; in fact, its streets and squares are named after it. Plaques and street signs carry the names of Mozart, Rossini, Gounod, and others. Bus shelters are called “Beethoven” and “Europe”—epochal grandeur confronted with assorted shapes of prefab concrete. When the “bankruptcy” of the ideals of the welfare state becomes a matter of consensus, policymakers usually blame the buildings, and order their removal as if they were statues of Lenin or Saddam Hussein. On one occasion the composer Jean-Michel Jarre accompanied—celebrated, in fact—the demolition of a public housing estate in Meaux with a spectacular synthesizer concert and light show.1 Remnants of large-scale urban planning projects are being replaced with low-density urban sprawl; aging “rational” grids have made way for parodies of villas and castles.

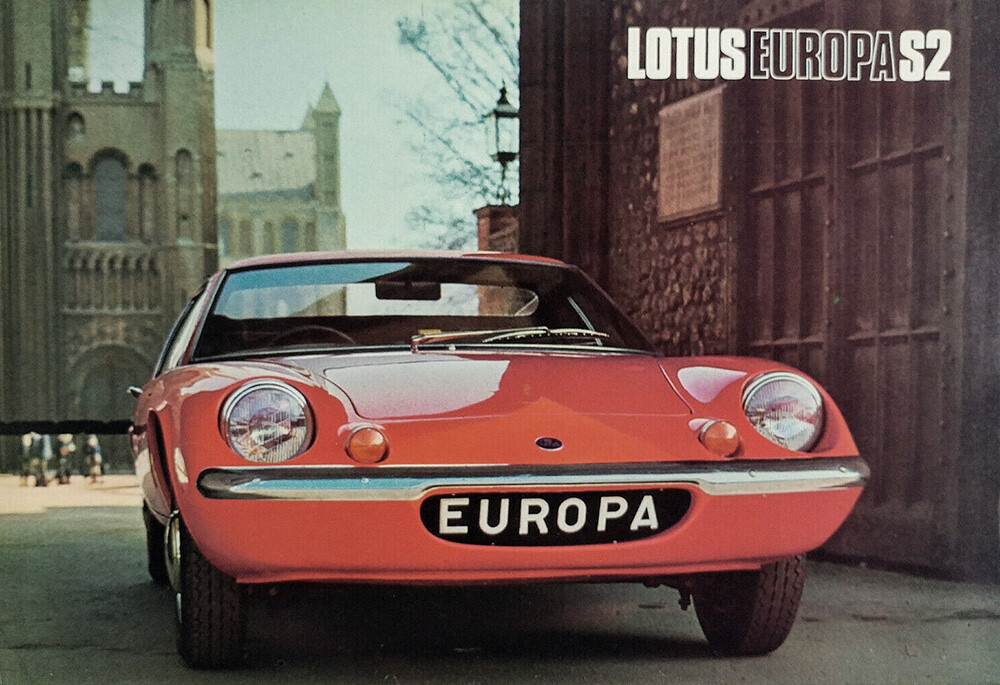

In the early 1970s, perhaps the word “Europe” resonated differently. Memories of World War II were fresher. Europe, as a streamlined ideal, would bring to mind something abstract and futuristic, like the Lotus Europa sports car, manufactured in the UK in the early 70s around the same time Fontbarlettes was planned and built. Memory could come to the aid of this abstract European utopia by providing an extensive repository of reliably historical figures—composers, writers, scientists, politicians, as well as battles, cities…

Just now, these European symbols seem to be on strike, much like Fontbarlettes’ local youth, and indeed all of France. A Fontbarlettes blog site shows an image of a burnt car overwritten with the word ROSSINI, in pragmatically disrespectful sans-serif.2 The name of the composer Gioacchino Rossini (Bologna, 1792–Paris, 1868) now merely indicates the coordinates of a torched Peugeot. The names that serve as Fontbarlettes’ heroic European way-finding devices are gambled on a world in which common memory is expected to ensure future coherence; the lack thereof is what is at issue. A bygone world of grands hommes is confronted with the multi-ethnic, multicultural reality of Europe today.

The French banlieues have developed something the sociologist Loïc Wacquant calls “advanced marginality,” a tremendously powerful condition with regard to the condition of border, or periphery. With a particular focus on the situation in Paris, Wacquant evokes “the trinity of ‘sans’ recently anointed in the French political debate (the job-less, home-less and paper-less migrants).”3 Revamped (historical) city centers, meticulously styled and kept, become “global destinations” for capital, culture, and investment, while cheaply and quickly constructed urban peripheries become ever poorer, harder to reach, and more difficult to leave.

Center-periphery oppositions like these are increasingly found as borders within Europe. According to the French thinker Étienne Balibar, there are “modes of inclusion and exclusion in the European sphere.”4 Europe is a “borderland,” anything but the patchwork of peace and prosperity conforming to the EU’s official brand image. As the abstract contours of Europe sharpen, it is as if we thought we saw a friend or relative in the distance who, as he approaches, turns out to be someone else completely.

As Europe makes progress toward greater formal unity, it moves away from the memories and symbols of the past that had previously rendered the process of integration meaningful and coherent. The theorist Avishai Margalit outlines the complexity of shared memory, and the devices used to ensure it:

In modern societies, characterized by an elaborate division of real labor, the division of mnemonic labor is elaborate. In traditional society there is a direct line from the people to their priest or storyteller or shaman. But shared memory in a modern society travels from person to person through institutions, such as archives, and through communal mnemonic devices, such as monuments and the names of streets. Some of these mnemonic devices are notoriously bad reminders. Monuments, even those located in salient places, become “invisible” or illegible with the passage of time. Whether good or bad as mnemonic devices, these complicated communal institutions are responsible, to a large extent, for our shared memories.5

Recent achievements of and within the European Union such as the single currency and the enlargement process are majestic geopolitical facts. But they are hard to remember as meaningful in and of themselves. They are easier to remember for what they do. Europe’s inhabitants often do not register its achievements as historical milestones. Instead, they see them as mere matter-of-fact life conditions. This, in turn, could secretly constitute the deepest sense of belonging one may ever feel. What goes unquestioned in the daily grind, perhaps, is the identity.

Europe: the Endless Think Tank?

In Amsterdam in June 2008, an audience of over 1,000 people gathered to attend “Identity, please!,” a conference on the identity of Europe. This intellectual Rock am Ring featured a heavyweight line-up of speakers including George Steiner, Francis Fukuyama, Sarah Rothenberg, Michael Ignatieff, Avishai Margalit, Adam Zagajewski, David Dubal, Allan Janik, Lewis Lockwood, and Roger Scruton, among others, chaired by Rob Riemen, director of the magazine and think tank Nexus. “Identity, please!” pondered the grand question of shared memory in the European identity, and the tricky issue of the role of culture, the arts, and humanism. The intellectual mood was accordingly drenched in melancholia; from the outset it was clear that a decline in European culture and a withering away of public awareness of its meaning were already accomplished facts. Keynote speaker George Steiner—announced as “the last European”—compared music, mathematics, and poetry in their competitive aspiration to be the mother of the Arts. After Steiner’s talk came a debate on the contemporary relevance of Petrarch, Beethoven, and Wittgenstein. When Riemen invited Allan Janik to speak for his dead master (“If Wittgenstein were here today, what would he say?”), Janik responded that Wittgenstein probably wouldn’t have been happy with what we are doing now—implicating the conference, not Europe.

Volumes are written, conference centers packed, NGOs funded, debates fueled by the questions of European identity, unification, and governance. Think tanks and academia produce page-turners like Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century, The European Dream, and The United States of Europe. Each of these titles heralds the multilateral concept of power used to build European integration and create European influence, opposing it to the more old-fashioned political and military deployment of direct coercion.

Wielding the “power of weakness,” the European Union presents a new brand of political legitimacy. The promise of EU admission is a major source of policy and governance reform in potential member states, without the need for authoritarian command. Europe wields a form of network power, providing incentives to conform to the standards of the club. The EU ultimately offers its prospective members the choice between membership and oblivion—as Mark Leonard argues, “Europe doesn’t change countries by invading them: its biggest threat is having nothing to do with them at all.”6 The handshake of EU admission is wielded as a power without power—one of a long series of oxymorons shaped to fit the EU.

The irony is that the manifold idealist definitions of the European project developed in think tanks and academia peacefully coexist with an unprecedented surveillance and fortification of outer and inner borders. Europe is ultimately a speculative object, which easily lends itself to academic debate, scholarly research, policy experiments, cultural integration, and artistic and cultural exchange, on the condition that none fundamentally affects the other. All realms coexist peacefully behind protective walls under the bleak stare of CCTV and data mining. This is only a logical extension of “power sans.” The “surveillance state” of Europe after the Cold War is a place where obedience and submission no longer need to be enforced by threat, because surveillance has been internalized. As Mark Leonard observes:

The French philosopher Michel Foucault showed how, from the nineteenth century, advanced societies moved from relying largely on the deterrence of visible expressions of might to discipline enforced by making potential subjects of power visible, through regulation, official papers, CCTV and prisons. Foucault argues that the shift from spectacle to surveillance allowed modern societies to be policed at a fraction of the cost of the ‘Ancien Régime’. The key was finding ways to record and monitor the behavior of citizens in a systematic way through the development of timetables, identity cards, photographs, medical records, and laws.7

Advanced Marginality and Inner Borders

Despite the European project trespassing national boundaries and overriding national interests, its progression cannot be endless. The threshold of membership cuts through regions and former empires, which have cultural, linguistic, political, and religious ties predating the EU network. It is the rationality of that network which is also its weakness. Consequently, the border with Europe’s “outside” is becoming an ever more radical and ever more irrational threshold. A border between the Netherlands and Germany (once fundamental, now superseded by Schengen Europe), is a less elementary boundary than the one between the European Union and Turkey, a potential member state.

The European advance stalls in east- and southbound directions as it enters the former Russian empire and the Arab world, respectively.8 The EU’s difference from its outside becomes simultaneously defined in cultural, historical, and religious terms (politicizing it)—in spite of the fact that the very experience of large differences and the continuous development of new cultural hybrids, have become an essential element of life in Europe and are perhaps the essential element of inhabiting a democratic space. As the progression of its outer border stalls, the EU will at some point face the limits to its own brand of tolerance and diversity.

The EU’s official ideology of cultural diversity and tolerance is paired with a collaborative program of border management. Much of this program is executed by a Warsaw-based agency called Frontex. Curiously, Frontex is located close to the EU border, far from the EU headquarters in Brussels and Strasbourg. The porous walls of the European Union move increasingly away from the mainland to camps and prisons constructed in outposts like Ceuta and Lampedusa, and to facilities in various African countries serving the supreme ethical goal of counteracting human trafficking, yet in practice also working to stem illegal immigration. Since Roman times, a city’s walls have been monuments to its integrity, ordering clear-cut divisions between friend and enemy, relative and stranger, ally and invader (the terms around which political debates regarding citizenship are currently centered). Europe’s contemporary city walls are degrees more advanced and sneakier; inside the borderland, the walls repeat at every checkpoint and with every camera’s eye.9 The logo of Frontex, set in square capitals (as found on Trajan’s Column in Rome), reads: LIBERTAS SECURITAS JUSTITIA.10

Meanwhile antiglobalists, G8 and G20 protesters, media, and border activists make efforts to organize an expanding network of resistance against the way the world—and Europe in particular— is governed. In a system of transnational political interdependence, political accountability becomes an issue; it becomes difficult to determine who is responsible, and whom to address. The protesters’ nodal points are the “summits” where this elusive regime of networked governance solidifies. Potentially, the impending conditions of life insecurity under the financial crisis could unite class strata into new alliances. The UK Ministry of Defense recently published a bleak report on future “strategic trends,” stating that “The middle classes could become a revolutionary class, taking the role envisaged for the proletariat by Marx.”11

The new revolutionary class has already been theorized; and it might congregate under the compound flag of Michael Hardt’s and Antonio Negri’s idea of the “multitude.” The term implies how internally differentiated the coalition is, as a “network of singularities.”12 When a seemingly isolated incident triggers the multitude to gather around a much bigger cause, its target may be any form of government or business—national, post-national, imperial, or neoliberal. For example, massive riots broke out in Athens in 2008 after a police officer shot a 15-year old student. Subsequently, the riots became about “capital, the EU and its parties,” as Aleka Papariga, head of the Greek Communist Party, put it. “The people must make use of their experience. The parties that lied to them about Maastricht, about the EMU, are lying to them now as well.”13

The Greek protests culminated in a temporary occupation of that most prominent among European historical symbols, the Acropolis. Meanwhile, the protesters’ modalities of social organization were, and continue to be built around the semi-private agora of online social networks, which account for new forms of pragmatism. For example, on the social networking site Twitter, the Greek riots were simply called the “griots.”

Crisis Europe and the Architecture of Protocol

In early 2009, with the financial crisis spreading, the Netherlands were hit by an advertising campaign produced by the global fast food chain McDonald’s which centered on the “Euro-” prefix. The campaign made a terrific—and terrifying—point: McDonald’s hamburgers, an American invention for sure, were shown in an unappealing, plain design under the caption “Euroknaller,” indicating their discount pricing.14 The “Euro-” prefix, while in theory an all-purpose promoter of the idea of Europe, in practice designates various standardized, prefab products, which are always, first and foremost, cheap. Mozzarella di Bufala is never “Eurocheese,” Coppa di Parma will not be known as “Euromeat.” Regulations now protect the local and regional denominations of almost every type of food, but the “Euro-” prefix is freely employed to say “discount.”

The effects of the post-historical virus on display in Europe’s treatment of its own key symbols become most poignant in the design of the Euro banknotes. Since their introduction in 2002, the Euro banknotes have generally failed to bring forth something as significantly symbolic and memorable as the national currencies of the Eurozone countries they replaced. Besides their emphasis on invisible anti-counterfeiting markings turning any “visible” design gesture into decoration (an electronic prison liberating design from any “functional” alibi), the Euro notes display a decidedly post-historical interpretation of European heritage.

In 1996, the European Central Bank announced a competition for the art to be displayed on the forthcoming notes. The contest was won by Robert Kalina from Austria, with a design proposal inconspicuously called “T 382.” The buildings drawn by Kalina as Euro art do not actually exist; they are the entirely fictional mash-up of various European architectural styles, turned into an anonymous parody of a hybrid. With no single nation state being prioritized over another, no hearts beat faster and no tears are shed over the European symbols proposed by the in-house designer of the Austrian National Bank. The cost of this all-encompassing gesture is a radical loss of meaning; the Eurozone having become an architecture of protocol, a historical non-place, a “Eurohouse” stretching into nothingness. The handshake of historical building styles from across Europe denounces nationalism and self-interest, but in doing so also eradicates all other emotions, until an utterly sterile amalgamate of empty formal gestures is achieved.

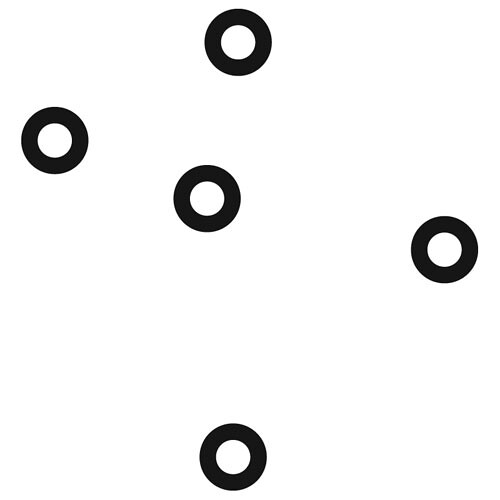

The Euro’s invisible security features are far more important than its exterior characteristics. Hence, “meaning” is transferred from the symbolic function of money as a signifier of a common European cultural, historical, geographical, and monetary space to that of technological protocol. In 2002 the computer scientist Markus Kuhn discovered a graphic pattern comprised of five rings on the Euro notes. It turned out to be the mark preventing them from being photocopied or scanned by alerting any software to interrupt the reproduction process. Although the same constellation is present in banknotes of countries from around the world, Kuhn named his discovery the “EURion Constellation” after the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) name for Euro and the constellation Orion, which the figure resembles.15

Once, “early” EU iconography showed Europe as a building under construction, or Europe as a ship with sails set in the national colors of member states’ flags. Despite their inspirational charm and iconographic power, these designs wanted Europe to appear as sovereign force, rather than as an evasive protocol power. If an architecture of protocol is the lasting residue of the loss of historical meaning in Europe—think tanks notwithstanding—the hidden security imprint of Kuhn’s “EURion Constellation” is not the sideletter, but the contract. It may turn out to be much more of an iconographic invention than hitherto acknowledged for a condition in which European identity has been relegated to the spaces and standards of protocol, and its microscopic city walls.

The writer and thinker George Steiner, keynote speaker at the “Identity, please!” conference organized by Nexus, glorified Europe as the place where streets and squares are named after writers, scientists, and artists, where proper names are saved from oblivion by people wandering the public spaces of their cities. “The shared culture we have is the culture of the cities,” Steiner said in a 1995 interview. “When you come to Europe, what strikes you immediately is the great diversity of all the cities, each one with its historical moment of grandeur, its historical past being engraved in stone and there to be admired. And therefore, this is our sharing, this is what we have in common.”16 George Steiner personifies an entire civilization; the implausibly well-read expert of experts who spends long solitary hours in his extensive library with the books of his fellow Greek, Roman, French, and German grands hommes. The child of an Austrian Jewish family, Steiner has lived through the decline of Mitteleuropa and its descent into inhumanity and mayhem. When asked about the allegedly elitist nature of his Europe of ideas and achievements, engraved and embossed on street signs, walls, and monuments, Steiner replied that:

There is very great anger and bitterness from human beings who have felt left out, who were never elected to the club, and that anger and bitterness is increasing all around us. There is, I hope, among those of us who have been privileged, and very lucky to be in the club, some severe self-questioning: we must ask ourselves what the price for this privilege of discourse was.”17

The next stage—perhaps liberating—is a Europe without history or form.

The French artist Cyprien Gaillard has used video footage of this demolition in his 2007 piece Desnianski Raion.

See → (accessed February 1, 2009).

Loïc Wacquant, Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008), 245.

Étienne Balibar, We, the People of Europe? Reflections on Transnational Citizenship, trans. James Swenson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 3.

Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), 54.

Mark Leonard, Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2005), 6.

Leonard, 39.

Frits Bolkestein, a former European Commissioner for the internal market, taxation, and the customs union, and a fierce opponent of Turkey’s admission, rhetorically asks: “What is the basic identity of Turkey? We are all formed by our history. Turkey has a marvellous history, in particular of the heyday of the Ottoman Empire. But it is not a European history. Europe is marked by the great developments of its past: Christianity, Renaissance, Enlightenment, Democracy, Industrialisation. Turkey does not fit in that mould.” Frits Bolkestein, “Don’t let Turkey in,” November 2006.

As the historian Karl Schlögel, one of the most realistic and yet lyrical observers of Europe, puts it: “The door we used to go through is now a double one: the traditional, physical door and the electronic one. The public sphere is armed. Mounted cameras swivel automatically. They face the empty space that is lit up by spotlights, the area that people cross from time to time. The gates are guarded. In the lobbies, those who check all movement, faces, bags, and identity cards have taken up position discreetly yet demonstratively. No movement without supervision. The security check has become routine. We have grown used to showing our IDs and passports, to looking at the camera, opening our bags and briefcases. Wherever there is security, there is something of importance. The important things are in the capitals. The pieces of equipment used in security are monuments to importance. Security-free zones indicate that coverage is not complete. Security crosses borders. It is one of the most important indicators of the speed at which Europe is coming together.” Karl Schlögel, “Archipelago Europe,” October 2007, → (accessed February 1, 2009).

See → (accessed February 1, 2009).

Antonio Negri, “The Monstrous Multitude,” lecture delivered at the Volksbühne, Berlin, October 6, 2004; published in Empire and Beyond, trans. Ed Emery (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008), 47.

“Ιnterview with Greek communist party leader Papariga,” → (accessed February 1, 2009).

The Dutch neologism “‘Euroknaller”’ is hard difficult to translate, but would might be rendered in English as something like “‘Euroblast”’ or “‘Eurexplosion.”’ in English

See the EURion constellation constellation as “‘discovered”’ by Markus Kuhn at →, (accessed 1 February 2009).

George Steiner, “Culture: the price you pay,” in Richard Kearney, States of Mind: Dialogues with Contemporary Thinkers on the European Mind (New York: New York University Press, 1995), 83.

Ibid., 84.