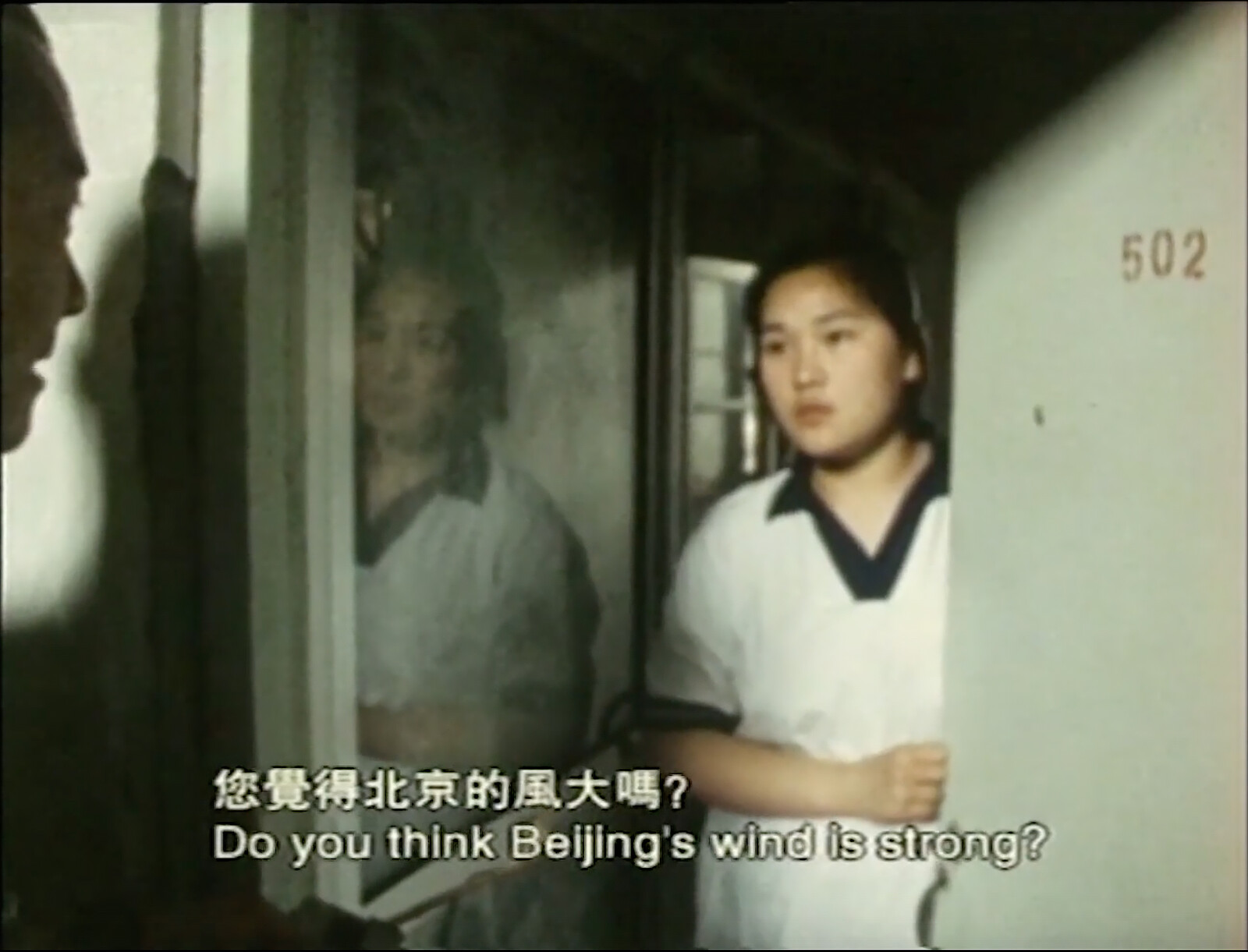

“Is the wind strong in Beijing?”

So the filmmaker and multimedia artist Ju Anqi asked unsuspecting members of the Chinese capital’s public in his gonzo film There’s a Strong Wind in Beijing (1999).1 Through the repetition of this seemingly innocuous but mischievous question, to which it turned out there could be no sanctioned, ideologically agreed-upon, answer, Ju revealed more about Beijing residents’ varying attitudes toward their state, their country, their city, its history and its changing politics than any more straightforward question might have done. “It’s strong, strong, it’s strong” a classroom of students choruses in unison, eyeing their teacher throughout for approval; “No… well. Not as strong as it once was,” an old man laments; “Today there is a warm wind only because so many guests and family have come to celebrate,” a jubilant newlywed groom declares into Ju’s microphone at the church altar; “but what do you mean?,” many other respondents ask the filmmaker in return, pressing on him to find out which precise state department he represents. Or, put otherwise, well—who are you to ask me how strong is the wind in Beijing?

Pursuing a similar strategy to Alfredo Jaar’s Studies on Happiness,2 in Anqi’s film the answer as to the actual strength of Beijing’s wind becomes itself incidental to the cascading process of further interrogation that such an unexpected question can ignite. Was the wind stronger than before? What could it mean to ask such questions in an environment where questioning itself is discouraged? What can questioning unleash as an activity?

Today we are accustomed to the apophatic gesture of free-speech fundamentalists and far-right demagogues, who use the flimsy legal cover of “just asking questions” to broadcast ever more widely the most violent and reactionary forms of hate speech.3 As has been shown by the recent wave of pogroms in the UK, the so-called “forbidden” questions pursued by an increasingly globalized neo-right, from Le Pen in France to Farage in England, but also by the centrist governments who seek to placate them, have predictably violent answers. Which is to say they ask questions to myopically shut down avenues of critical thought, rather than to open new ones up. These are, not incidentally, still the questions most in alignment with the architecture and incentive structures of large social media apparatuses and content-farms—the very questions that drive engagement.

In resisting this enclosure of thought, art and theory continue to be instructive, if not essential activities. The late Lawrence Weiner memorably declared that “the purpose of art is to ask questions… it doesn’t answer anybody’s question but gives them the means to answer a particular question at a particular moment.” 4 All the better when those questions can provoke a certain illuminating friction with the contradictions of one’s environment and disrupt the automaticity of one’s learned responses, remaining themselves ambiguous or unanswered—because unanswerable.

This third issue of e-flux Index, bringing together all the content commissioned and published by e-flux between April and May 2024, contains many such unexpected and unanswered (or unanswerable) questions across its 76 contributions, many of which cut across and reach beyond existing disciplines and borders: “Who is willing to care?”; “Who is the addressee at the end of the regulated pipelines of the English language?”; “Yes, but is it edible?”; “Why does everyone hate college students?”; “Is some form of suffering the condition for the emergence of an organic type of intelligence?”; “What does it mean to make a film today, in 2024, when most of our image consumption has been transferred to other (smaller) screens and other media?; “How to represent history?”; “Whose lives are worth remembering—or even, living?”; “How is it possible to speak the language of imperial renaissance and decolonization in the same breath?”; “Today is which day of the revolution?”—“Are these all just notes for a poem?”

The hope is that these questions will in turn birth new questions. This Index is arranged into eleven thematic sections that each refract and reflect small glints from one another: Flatlands of the Mind; Twenty Thousand Blinks; “Woman, Life, Freedom”; Characters in a Landscape; Structures that Want to Become Other Structures; From the [■■■■■] to the [■■■]; Planetary Acupuncture; Jina, the Moment of No Return; Pulverized Histories; One Size Does Not Fit All; and A Jacket with Reversible Lining.

*

Index #3 begins by jogging our memory with a section titled Flatlands of the Mind. Here, linked together like so many adjacent knots in a handkerchief, are pieces united by their interest in “mnemotechnics”: the technology of remembering in a forgetful era. Beginning from Alessandro Bosetti’s journey into the “the dark realm of pure memory” in the work of Giordano Bruno, Alvin Lucier, Jorge Luis Borges, and Robert Ashley, we move on through Brian Dillon’s considerations of the German writer W.G. Sebald’s mnemotechnical approach to photography, references to lukasa (mnemonic devices used by the Mbudye Society of the Luba peoples) in the artist Agnieszka Kurant’s discussion with science fiction writer Ted Chiang, and the Danish architect Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag’s description of an innovative project whereby abandoned buildings in rural Danish communities were cut in two: revealing the accretion of collective memory.

When you’ve watched enough films, it can be hard to distinguish where one ends and another, or indeed your own memories, begin. Twenty Thousand Blinks brings together reflections on the state of contemporary imagery, from photography to moving image to appropriation art, that respond in part to this condition of graphical oversaturation. Reporting from the 2024 Cannes film festival in a lively two-part essay for e-flux Notes, Pietro Bianchi discerns a notably meta-cinematic tendency to many of the films in the competition. Meanwhile strategies of appropriation and dissimulation appear in reflections on the work of Vija Celmins and Arthur Jafa. Finally, Boris Groys interrogates the claims made for the “accessibility” of digital imagery—asking, “Why is it that these images and not other images are shown to us?”

The April 2024 guest-edited issue of the e-flux Journal presented the first freshly commissioned body of work to appear translated in English from feminist activists involved in the 2022 Jina Uprising in Iran. These protests began following the brutal murder of Jina Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman beaten to death by the Iranian morality police. Breaking somewhat with the combinatorial logic of the Index, we have chosen to present the entirety of this thematic journal issue in two sections entitled “Woman, Life, Freedom” and Jina, the Moment of No Return respectively. Presented together, these texts from various participants in the Uprising—in the words of the issue’s co-editors Ghoncheh Ghavami and Bahar Nooirzadeh—powerfully move “against the abstractions of our hyper-mediated time, in writing [that] posits the body as a mode of inscription, as history incorporated, tracing its enforced subjections and emancipatory convulsions through the singular mutations of each body that contributed to the feminist revolution we witnessed.”

Moving from the emancipatory convulsions of Iran to the geothermic convulsions of our ever-warming planet, Characters in a Landscape explores the metabolic rifts of the climate crisis. These range from a text exploring the surprising, shared lineage of Exxon oil extraction and autotune, as revealed in Andrius Arutiunian’s work Synthetic Exercises, through to Octave Perrault’s speculative essay envisaging an architecture beyond the “abundance of fossil fuel energy.” Reviewing the first self-styled “climate biennial,” Aiofe Rosenmeyer meanwhile questions the subtending of art to mere illustration of scientific hypotheses in such settings, while Filipa Ramos applauds the “holistic sensibility” undergirding Joan Jonas’s “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral” drawings.

The director Pier Paolo Pasolini characterized his semi-autonomous screenplays as “Structures that Want to Become Other Structures.”5 The section bearing this title links together several forms of other notational structures like so many nodes in a flow chart. A magisterial essay from the late architecture critic Anthony Vidler explores the “diagrammatic panorama of the history of architecture” pursued by James Stirling’s Wissenschaftszentrum für Sozialforschung (Social Science Center, or WZB) complex in Berlin, meanwhile Rômulo Moraes’s review of a Raven Chacon retrospective addresses this artist’s ongoing approach to “notation in the expanded field.” Elsewhere, texts from Robert Ashley and Alice Notley elastically stretch and stress-test the capacities of notation, composition, and improvisation.

From the fretwork of the composer’s sheet music, we pass to the frantic scrubbings out of the censor’s pen, in a section titled From the [■■■■■] to the [■■■].6 Here several pieces inevitably respond to the increasingly intense climate of cultural censorship directed towards those protesting the ongoing Gaza genocide, including Jonas Staal’s letter to the German DAAD in rejection of their nomination of the artist, and Daniel Spaulding’s trenchant examination of what has been termed “philosemitic McCarthyism” as it has been expressed against student protestors on college campuses.7 We also learn how the cat-and-mouse navigation around censors or other authoritarian conditions of speech has given a particular shape to several artistic practices, from the pioneering Black Wave filmmaker Želimir Žilnik to the codified, indirect, “private world of symbols” developed by the Burmese artist Po Po.

Planetary Acupuncture takes its title from the Future Foodscapes Research Unit, who elsewhere in this issue use this phrase to denote “selective interventions that, while discrete, wield the capacity to initiate cascading changes across the system’s multiple layers and scales.” Such interventions—as deliberate and delicate as acupuncture needles, reparatory rather than wholly destructive—can be seen in the pedagogical approach undertaken by the Santander praxis programme, as described here by the Fluent collective, and can also be sensed through Canada Choate’s portrait of Benjamin Buchloh’s ongoing critical project. Questions of reuse, renovation, and the costs of paying close attention also surface in three texts here sourced from an ongoing e-flux Architecture project “Framing Renovation,” which speculates on how through “new strategies of care, we might be able to find the future in what we still have from the past.”8

Yet for all the current talk of repair, the Pulverized Histories of colonialism, imperialism, and the open wounds of expansionist wars can often stultify efforts to “find the future.” In May 2024, with the regularity of a brown-enveloped tax slip, the 60th International Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, opened under the title “Foreigners Everywhere” as Israel’s offensive in Gaza continued unabated and the war in Ukraine underwent a new phase of intensification. Like several of the other biennales reviewed in this section, Pedrosa’s curatorial strategy sought to foreground artists and practices that had been peripheralized by historic violences or discrimination. Beyond the temporary heterotopias of Biennale pavilions, two pieces in this section (from Debora Silverman, and Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal respectively) confront the permanent architectural “profanations” of the colonial (and fascist) built heritage in Congo, Belgium, and Sicily.

From the protection of cultural diversity (against the forces of homogenization and/or modernization) to food monocultures, we are increasingly cognizant that One size does not fit all. In this section, the Future Foodscapes Research Unit critically explores the “operational landscapes” that permit and sustain an increasingly monolithic global diet (in which a mere fifteen plant species constitute 90% of global caloric intake)—concluding by ambitiously staking out a “food regime of the future.” Rocio Colorado elsewhere taxonomizes the legacy of architectural uniformity as it was expressed through the prefabricated housing estates of the post-war period, in this case the fortress-like Corviale estate in southwestern Rome, and its deterioration. Jace Clayton’s pointed critique of Pedrosa’s Venice Biennale meanwhile explores the “differences that make a difference, and those that don’t,” identifying the slippage from decolonization as a process here into decolonization as a theme: a theme that risks homogenising difference through a “false equivalency.” Finally both Boris Groys and Miri Davidson identify the rhetorical slight-of-hand that has enabled far right intellectuals such as Alexander Dugin and Alain de Benoist to now articulate their ethnonationalist ambitions in a vernacular of “decolonization.”

Like A jacket with reversible lining the pieces that conclude Index#3 all in some way code-switch, scrambling reductive binaries and essentialisms to scope out ways of living and producing beyond regimes that demand legibility as one thing rather than another. These include Xiyadie’s Rorschach-like papercuts—which portray tender scenes of queer love through his mastery of an ancient medium—Tausif Noor writing on artists and their day jobs, McKenzie Wark’s portrait of the trailblazing trans actress and artist Candy Darling (“The public, visible trans woman provokes an anxiety about the sexed body in general”), and the Robida collective writing of their work in a cross-border village community that “not only demarcates two countries, but also two climates.” The issue ends with Nathan Brown’s phenomenology of the solar eclipse that happened on April 8, 2024: an instant in which the symbolic order was temporarily suspended, and we got to witness “Day as well as Night.”

— Berlin, August 2024

Anqi’s first film, it was shot illicitly on thirteen reels of 16mm Kodak Eastman film, seven of which were expired.

In this work, the Chilean conceptualist pursued a seven stage multimedia project which began from him approaching Santiago pedestrians living under Pinochet in the late 1970s, asking them all one deceptively simple question: “.ES USTED FELIZ?” (are you happy?).

It was precisely through these rhetorical means, through “just asking questions,” that far-right agitators like Andrew Tate and “Tommy Robinson” (f.k.a. Stephen Yaxley Lennon) spread the incendiary falsehood that the suspect in the recent Southport attacks in the UK was an “undocumented migrant” called “Ali al-Shakati” who had recently arrived in the UK on a “small boat.” Responding to subsequent criticism of his own involvement in fanning the flames of the pogroms, recently elected Reform Party MP Nigel Farage once again ducked to seek cover in the interrogative mode, responding “I asked a very simple question—was this person known (to the intelligence services) or not?” See Edna Mohamed, “Southport Stabbing: What Led to the Spread of Disinformation?,” Al-Jazeera, August 2, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/8/2/southport-stabbing-what-led-to-the-spread-of-disinformation.

Lawrence Weiner, “The Means to Answer Questions,” Louisiana Channel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AscU8wKzbbE.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, “The Screenplay as a ‘Structure that Wants to Be Another Structure,’” American Journal of Semiotics 4, no. 1 (1986): 53.

In Germany, a Berlin court recently fined a twenty-two-year-old activist for chanting “from the river to the sea” at a demonstration, having declared the phrase “could only be understood as a denial of Israel’s right to exist.” In response to censorship, and in recognition of Berlin’s significant Palestinian population, an alternate version—“from Risa to the Spree”—sprang up on marches this year, namechecking a Syrian owned fast-food chicken outlet and the river that splits Berlin.

For “philosemitic McCarthyism” see Susan Neiman, “Historical Reckoning Gone Haywire,” New York Review of Books, October 19, 2023, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2023/10/19/historical-reckoning-gone-haywire-germany-susan-neiman/.

Framing Renovation is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana within the context of the 2023–24 LINA Architecture Program. It is edited by Nick Axel, Matevž Čelik, Nikolaus Hirsch, Mateja Kurir, Nuša Zupanc. See:https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/framing-renovation/.