Looking Up: Week #5

Jewels

Sandro Aguilar

2013

18 Minutes

Artist Cinemas

Date

Repeat: April 24-25, 2023

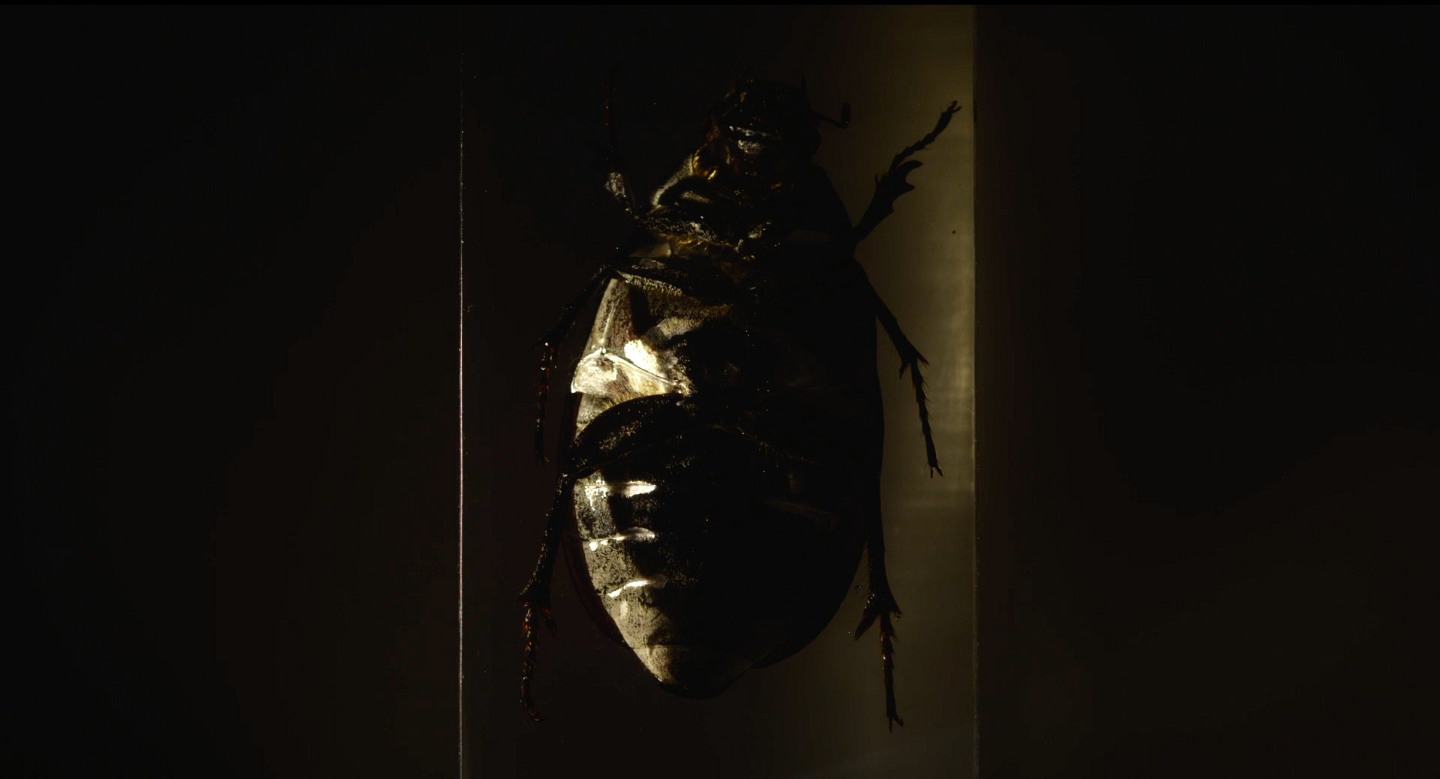

Hypnosis. Diapausing insects and a broken heart.

Jewels is the fifth installment of Looking Up, an online program of films and accompanying texts convened by Jorge Jácome as the twelfth cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Film.

The film is presented alongside a conversation with Sandro Aguilar by Francisco Valente.

Looking Up runs in six episodes released every Monday from March 18 through April 24, 2023, streaming a new film each week accompanied by a commissioned interview or response published in text form.

A conversation with Sandro Aguilar

By Francisco Valente

Francisco Valente (FV): There is a tendency to talk about the immaterial when describing the journeying into new worlds and universes. However, you seem very interested in real, tangible things, as if using cinema to take the audience on a journey that reveals how, in fact, we never leave the world we live in.

Sandro Aguilar (SA): I’m interested in immaterial things born out of tangible ones. My filmmaking process comes from my relationship with the tangible, such as light hitting a wall, or an object I choose to film because I see something in it that goes beyond its obvious function. Things that arouse my curiosity and creativity are those that make me think about who manipulated them, who abandoned them—and what has been forgotten. I film these things as traces of something I didn’t witness, so my films focus not on events but on their traces. It can begin with nothing; I’ve filmed without a script, or just with the memory of a script. I let my films transform themselves through the things and people I am working with, and I try to carry that energy from the film’s beginning right up to the sound mix. I make conscious and unconscious decisions that may transmit that same state of curiosity to the audience. In other words, my relationship to what I do is very instinctive.

FV: Cinema doesn’t show; it reveals. We don’t necessarily want to be shown anything when we look at our reflection in the mirror or at things around us—but we do long for a revelation.

SA: Cinema has not been that way for a long time, but rather has taken on a more basic and affirmative language. Jewels questions some of the essential things in cinema, such as movement, since part of the film is static. Still, time exists in immovable objects. I like to see people sitting and looking at immobility, and at the primal game between darkness and revelation, like a light that turns on and off. This primary state produces an interesting tension for the audience; it’s a film I enjoy watching in theaters. The audience is in a state of semi-hypnosis because they don’t see what they expect to see in a film. That kind of expectation motivates me.

FV: The film takes us on a seemingly otherworldy journey, but your work shows that such a journey doesn’t usually take us to another universe. Instead, it makes us travel within the same world we live in so we may see things differently. In Jewels, we’re seeing what lives inside these immobile objects: living stories, forgotten ones, intuitive and inexplicable things. It’s a bit like Chris Marker’s work, particularly La Jetée (1962), where a sort of spectator trapped in time looks for another world and realizes, on his extraordinary journey, that he’s stuck with the one he lives in.

SA: Jewels was like creating a gaze without a human element, suggesting something close to human extinction. It’s as if something mechanical had filmed it. I’m interested in the poetic emanation of the world’s dismantlement. The presence of a male and a female voice, in the automatic readings by devices, makes the film drift toward a love story between non-moving objects and fossils. They’re unaware of what they’re saying, just mimicking breaths and restlessness in a way that seems to suggest that these words come from sometime in the past. Today, the use of artificial intelligence, voice recognition, and text-to-speech is much more prevalent. At the time, I used primitive instruments to create an automatic system that chews on images and sounds in order to reflect a sense of absence to the audience.

FV: Humans always try to use technology to find other mechanisms and languages that can communicate better than the ones we have—something that is doomed to fail, as suggested by Jewels. It’s a genuine human impulse to seek to replace what we have with something else that seems better. Your films touch a lot on the issues of communication and language, even though there are few words in them.

SA: As an “extinction film,” Jewels has a male voice alternating with a female one, reading that he had an awful dream he couldn’t tell her about. The music conveys a romantic feeling. Still, it is a simulacrum of communication, a bit symptomatic of our own communication today. Communication exists but it is no longer by individuals, but rather by groups that say the same things in multiple voices, like a choir. Socrates told Plato that writing was the beginning of ignorance; it made us dependent on something outside of our consciousness, as if we needed to write down content to activate it later. Today, the profusion of thoughts and ideas and convictions has become so great that these cannot help but be superficial. We are becoming less like thinkers and more like users of thought patterns. There are lines of reasoning in them, but getting people to actually think about what they are communicating or being exposed to is becoming more challenging. We are consuming synthesized thought.

FV: Are we increasingly confined to the same exchanges?

SA: Clearly. I have the same conversation with my fourteen-year-old son as with an actor who works with some of the most remarkable texts in the world. Everyone talks about the same things. When I write an email, my device already knows what I want to write. What other result will we get but the same letters, farewells, texts, and automatically written messages? I used to have one such message on my cellphone that said: “I’m a little late, sorry, I love you too very much.” We no longer express feelings; we’ve replaced them with automatisms.

FV: There’s a sense that things are coming to an end or have already ended in your films. However, they also suggest that something new might happen, and that we must invent a new language for it to come. Where do you see cinema in all this? I also think of Jean-Luc Godard, a filmmaker who was obsessed with language and with the end of things, but who also longed to create something new that could come after.

SA: I still work in cinema, so I can’t discredit its language and communication tools. But honestly, I don’t think audiences are as available as they used to be. It’s one thing to show you a film and talk about it afterwards, and quite another to show it to a group of people and get a collective reaction through a sum of individual consciences that influence each other. Audiences can read a film but they seem less able to communicate with it because the way they watch it has changed since my days as a filmgoer. Nowadays, they seem impatient and attracted to multi-layered forms that accumulate things confusedly. It doesn’t matter if it’s narrative, experimental, minimal, or baroque cinema: The audience’s openness to discovering the specific language of a film is decreasing. My connection to what I do still involves imagining, even if only virtually, that someone on the other side is paying attention. When that is gone, I’ll have to move on to a different area where I can feel the same communicative freedom and linear relationship to the audience—perhaps a new territory where I can talk to the viewer. Films are meant to be watched with a certain involvement, to take place in a spectator’s mind, something that can hopefully create thought or a dialogue with another audience member before returning to the filmmaker who can then think about it in their next film. All of this is somewhat gone nowadays. I don’t know how long we can keep pretending that cinema is the same as it was, or if we will move on to something different. But I also meet new cinephiles who’ve seen a film at fifteen that I did not see until I was thirty because I didn’t have access to it—new cinephiles in underground streaming. Perhaps this could help change things, bring back some of what was lost, or maybe reinvent it.

FV: Finding movies online and watching them at home is helpful. However, it doesn’t offer the same conditions as a movie theater. We are in a place where we play with the memory of who we were, with who we are now and what we want to be. The movie theater is the ideal place for this to happen. It offers the audience a journey through time, one I associate with the final journey of 2001: A Space Odyssey (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1968), where we go into space to discover something new and beautiful and terrifying, only to realize that we never left the place we live in. You seem to suggest we’re less available for that kind of experience and increasingly headed towards a different one where memory doesn’t play a role.

SA: What we are experiencing now is similar to a chalkboard at school, where things must be erased before one can write something new. I see parents walking babies in strollers without developing a relationship with them. A social experience dating back millennia—our mealtime interaction—is now a deeply sad experience, an intermission for clicking.

FV: Instead of “looking up,” as in a film theater, we are increasingly “looking down.”

SA: Yes, and this is a transversal thing. Our relationship to cinema and the way it is changing is a symptom of our relationship to reality, which is also changing. It’s terrible.

FV: I don’t want “terrible” to be the last word of our conversation. I want to talk about instinct and physical presences in your films. In Jewels, there is a microscopic interest in animals, and in discovering the animal within us.

SA: I try to be like a seismograph and catch small movements that may enunciate larger ones. I’m interested in minimal movement, like high blood pressure in insects, for instance, and in hypnosis. I work on the border between being awake and sleeping, alive and dead, and look for tiny sparks of communication—in other words, the first condition of being alive. A cell changes in the dialogue between its first movement and immateriality: That’s where communication begins. I like to believe there is transformation in everything, and communication at a microscopic level between living and dead matter, like a continuous journey of matter. That flow of energy is what makes us communicating beings. I am increasingly interested in untraceable dimensions, like the imagination, that allow us to relate to other beings and things, assign value, and change an object’s function, perhaps modifying personal and mutual perceptions. I like to work on how our consciousness acts on reality and transforms it into something else. That, for me, is the core of making cinema and the possibility that cinema holds within itself. It’s something subterranean, almost romantic.

-

Francisco Valente is a filmmaker and curator born in Lisbon and based in New York. His films have been shown at Curtas Vila do Conde, IndieLisboa, ZINEBI, Bogoshorts, Go Short, and Kortfilmfestival Leuven, among other places. As a curator, he has worked for IndieLisboa, Cinemateca Portuguesa, Anthology Film Archives, and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and published educational books on films by Joaquim Pinto, François Truffaut, and Steven Spielberg for CinEd, Cinarts, and Plano Nacional de Cinema. He is currently a curatorial assistant at MoMA’s film department.

For more information, contact program@e-flux.com.