Screaming from the Inside: Week #5

Two Sisters

Caroline Leaf

1991

10 Minutes

Artist Cinemas

Date

August 15–August 21, 2022

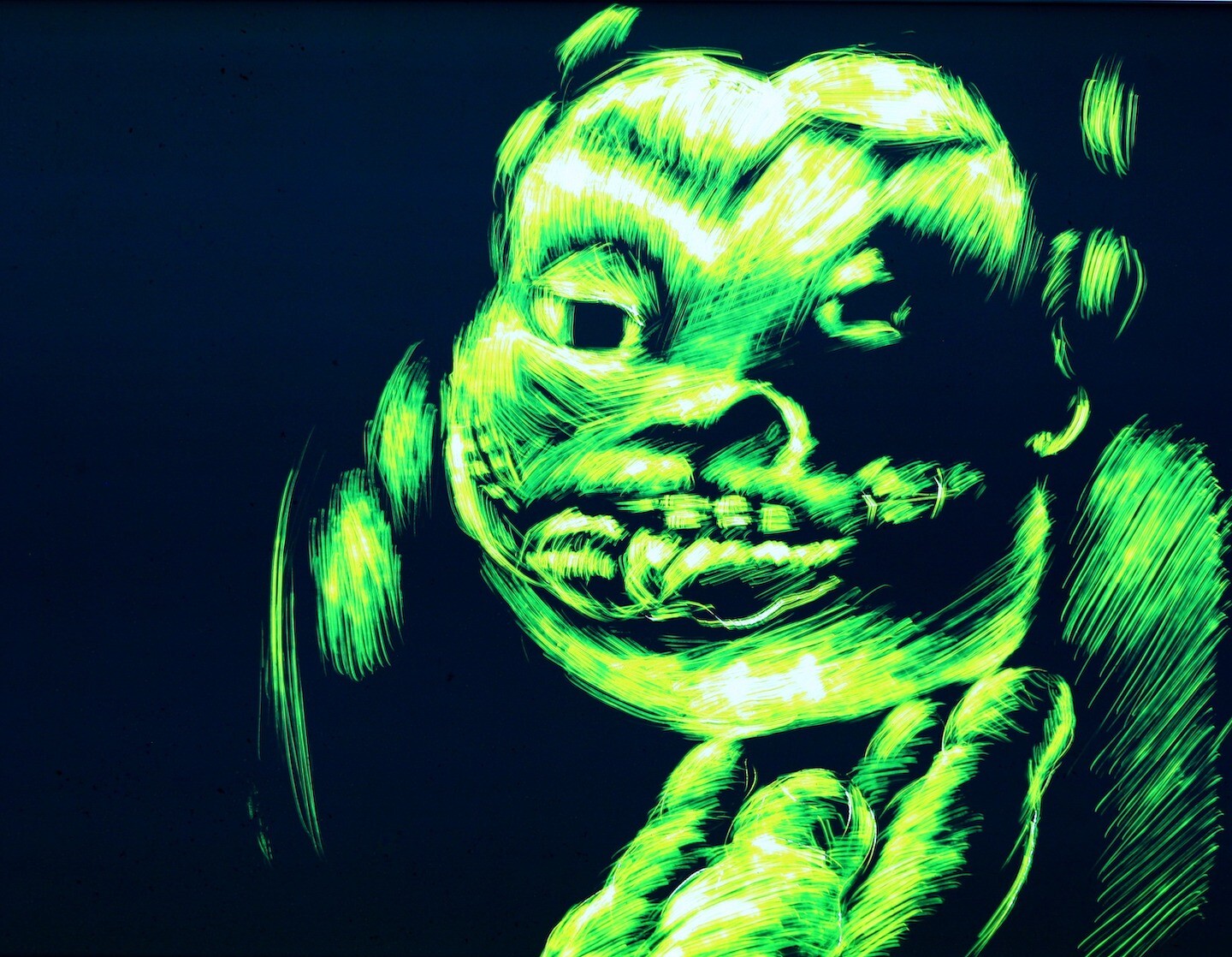

This animated short, etched directly onto tinted 70 mm film, depicts the story of two sisters: Viola, who writes novels in a dark room, and Marie, her only companion. Disfigured, Viola counts on her sister to take care of her and shelter her from the outside world. But when an unexpected stranger turns up on their front door, the sisters’ quiet lives are disrupted and their routine turns to chaos.

Two Sisters is the fifth installment of Screaming from the Inside, an online program of films and accompanying texts convened by Camille Henrot as the eleventh cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film.

The film is presented alongside a text response by Orit Gat.

Screaming from the Inside runs in six episodes released every Monday from July 18 through August 29, 2022, streaming a new film each week accompanied by a commissioned interview or response published in text form.

Stay, Stay, Stay

Orit Gat on Two Sisters

We’ve heard that one before. “Stay here, and everything will be like it was before.” Marie, who cares for her sister Viola, carries a heavy set of keys around with her. She is Viola’s warden and companion. Viola is a writer. She spends her days in a bedroom, typing, working alone. It’s just the two of them in the house and perhaps this is related to the fact that Viola’s face is scarred or disfigured. Her sister constantly reminds her of it, handing Viola a mirror while Viola writes. Marie is demanding, she wants Viola to commit—to her, to her writing perhaps, to their life, to their isolation. At the beginning of the short animated film, after being given a cup of coffee by Marie who rests it on top of the monitor of the computer Viola tries to write on, Viola wanders around the bedroom. She is enclosed, she is battling with words (she mumbles), she is battling with writing (she types), “that’s it” she says to herself, unconvinced. “Walk,” she edges her room, moving from one corner to another. When she’s back to her writing, the sound of the keyboard is unfamiliar, heavy, haunting. In the background, the music is tender, almost lulling. It’s like the soundtrack and the sound of her actions belong in, or come from, different stories.

The two sisters live alone on an island. How long have they been there, how did they get there, and why? The island and the room: two systems of isolation, two spaces of loneliness, compounded.

But then, an arrival. A man. A reader of Viola’s writing. He makes the journey. “Please,” he asks to be let in, “I’ve come to see Viola Gé.” He is carrying a book of her writing. “I’ve read everything you’ve written. Everything. Every word,” he assures her. He is enthusiastic. He looks at her. He touches her shoulder, he moves her hand away from her face. Tenderly. It’s like he, too, came from a different story. The sisters (or is it only Marie?) expect him to be shocked by the sight of Viola. He is not.

“Time’s up, visits over, time to go,” says Marie. She wants things to go back to the way they were, that is, her sister to go back to her room. Like the “madwoman” wife locked in the attic in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Mr. Rochester, Jane’s love object, is married to Bertha Rochester, the Creole daughter of a wealthy merchant in Jamaica. We know this from Mr. Rochester, who tells his wife’s story to Jane as an explanation of why they can’t be together. Jane Eyre is a first-person account of Jane’s life, still, the other woman’s narrative is left to be described by her (disenchanted) husband. Following some misfortunes and misunderstandings and two fires at Rochester’s grand home—one mysterious (and started by the “mad” wife); the second also sparked by the wife, and ends in her death and Rochester’s disfigurement (he loses an eye and a hand)—Rochester is free to marry Jane.

It’s not that Jane’s rise comes at Bertha’s demise. But the madwoman being locked in the attic enables the free woman to exist. There are so few ways for women to be, so few places to inhabit. There couldn’t be two women in that story, so one was locked up.

The sisters’ house is ill-defined, it’s composed of a bedroom, a few doors, many locks and keys. In the bedroom is the computer, and that cup of coffee, the bed, the corners to hit against. The door can be opened, still it acts as a barrier. But then that one, “stay here.” That, “everything will be like it was before.” Is there any comfort in the house? Can Viola even write there? A first reference to Virginia Woolf, but about the house (that is, the home), not the room: Woolf writes that in order to write she had to “kill the angel in the house”—the angel, that is, the woman, or the idea of the woman as pure, simply beautiful, sympathetic. Woolf had to end it before it brought an end to her writing. “[W]henever I felt the shadow of her wing or the radiance of her halo upon my page, I took up the inkpot and flung it at her. She died hard.”¹

Marie is not pure and Viola not beautiful. Still, they both enact feminine roles: Marie the caretaker, Viola the woman hidden in the attic. The woman Woolf writes about is also a social expectation, thus also limitation. And the violence of flinging an object is missing from the two sisters’ story, but it is hinted at. When the reader arrives, he is accompanied by horror-movie suspense. There is a barking dog, a cat hiding under a couch, the music tenses up, the knock on the door. Writing is solitary labor, also work that is deeply committed to the world. Writers and readers are intertwined, expect to be changed by one another. Marie reprimands Viola: “You send your stories out and this is what washes up on our shores.” The man is courteous, but he interferes.

You’d think the arrival of the stranger is the danger, but it isn’t. It’s just that it may change the story. It may interrupt the state of affairs. It may make things not what they were before.

A story can be retold. Jean Rhys’s 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea reimagines the story of Bertha Rochester. A prequel to Jane Eyre, it is set in Jamaica and tells of Bertha’s youth, which ends in an arranged marriage to the English gentleman who takes her away from her home, declares her mad, and shuts her from the world. In Rhys’s account, part of the reason for Rochester’s refusal of his wife is her Creole heritage. The other part of it? How her marriage meant isolation anyway. She was lost to the world. She no longer belonged to Jamaica nor to England; she had no one to care for her but a servant/warden and the husband who set this life up for her. Rhys, an English writer born and raised in Dominica, reimagines the nineteenth-century novel from a perspective that introduces questions that were not addressed in Brontë’s novel (to be fair, were rarely addressed in her time). Rhys writes about race, colonialism, and society.

“Like it was before.” As if there was never anything else.

Viola complies when the reader asks her, and writes a dedication in his copy of her book. “To a stranger who looks at me in plain sunlight,” she writes. He leaves, swimming away. Somehow, the book survived the crossing to the island. It must do so on the way back as well. Viola stays behind. Perhaps by choice. Now it is up to the reader, the viewer, the imagination: Will things be like they were before?

How are stories retold? Over time, with effort, flinging inkpots. In their famous feminist reading, The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), scholars Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar argue that the female characters in Victorian literature by women had to fall within the paradigm of Woolf’s angel in the house. They were rebels or pure, they conformed or were confined. Brontë’s depictions of Bertha, the disaster she embodies (and, later in the novel, sparks), are told from her husband’s perspective, thus cannot make room for a story of her freedom.

Viola and Marie, Jane and Bertha, Brontë and Rhys and Woolf; there are also the closed room, the disfigured face, the arrival of someone from another world. In a series of stories of isolation, all these points of contact endure.

“She died hard.” A second reference to Virginia Woolf: there’s another version of the lock and key—how they may be a necessity. A room of one’s own is not just a metaphor for how women require access to education, to time, to ways to grow as writers and artists. It’s also a practical need: Woolf writes that a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction. The cover of the first edition of A Room of One’s Own (1929) was drawn by Woolf’s sister, artist Vanessa Bell. It shows an arch encasing a platform. On it is a clock. Writing, time, passage. And the knowledge of that hard death. That writing is solitary, and at times requires a space away from society. “Every word,” the reader assures Viola. He’s read her every word. Even if the isolation is necessary, the connections live on.

¹ Virginia Woolf, “Professions for Women,” The Collected Essays of Virginia Woolf (London: Read & Co., 2013), 238.

-

Orit Gat is a writer living in London. She is a contributing editor at The White Review and Art Papers.

For more information, contact program@e-flux.com.