The Films of Amit Dutta: Week #5

Mother, Who Will Weave Now?

Amit Dutta

2022

25 Minutes

Artist Cinemas

Date

April 11–19, 2022

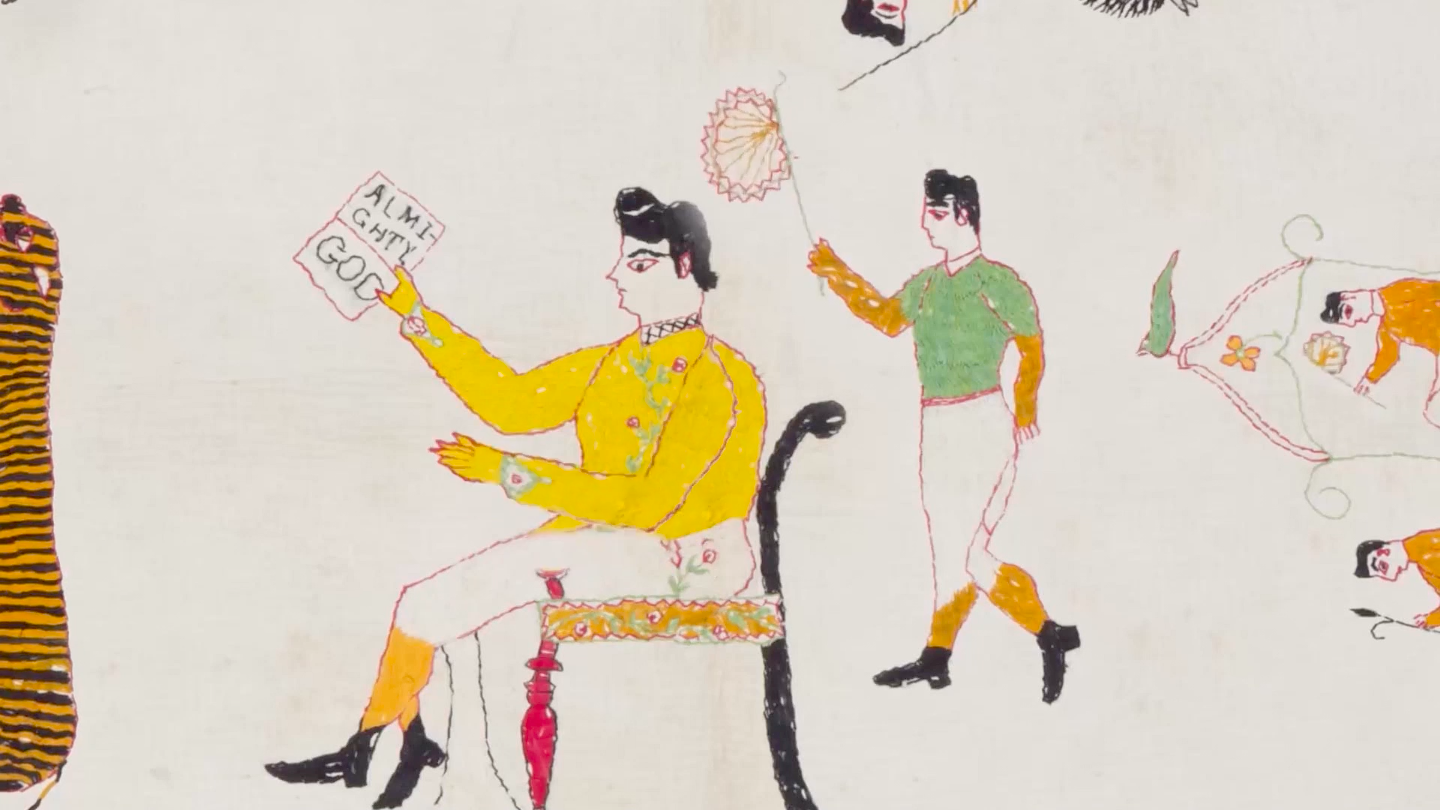

Mother, Who Will Weave Now? attempts to sample and mirror the grand tapestry of Indian textile tradition and history by interweaving snippets of Indian cloth on an editing table, using the poetic meters of classical Indian literature sewn together with the words and motifs of the weaver-saint Kabir.

Mother, Who Will Weave Now? is the sixth and final installment of The Films of Amit Dutta, a selection of films programmed by Iman Issa as the tenth cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film.

The Films of Amit Dutta runs in six weekly episodes from March 7 through April 18, 2022, and features six films by Amit Dutta accompanied by a conversation in six parts between Amit Dutta and Iman Issa, published in text form. A new film and part of the conversation are released every Monday. Each film streams for the duration of one week.

The program wraps on the last day, Monday, April 18, with a repeat of all six films streaming through Tuesday noon EST.

Amit Dutta in Conversation with Iman Issa

Part VI

[Read parts one through six here: I, II, III, IV, V, VI]

Iman:

In a previous conversation you had mentioned to me the urgent feeling of the need to look to the past. I was struck by this statement as I myself believe to have said this verbatim. At the same time the way you approach this past is unusual, as you seem to take large leeways in the way you deal with existing materials whether they are historical narratives, artworks, or even the systems they created. As viewers we rarely have access to that material, only bits and pieces that are rearranged and altered in multiple ways. We also get a sense that the material itself is not significant; that it is being used to point at other things. This is quite different from someone who approaches a tradition as a coherent system of knowledge that is to be applied according to its own rules. In your case these traditions are no more sealed than anything in the present. They are just as open and ripe for possibilities. Moreover it doesn’t seem the work is concerned with revealing any hidden essences to these traditions or the material emanating from them, but is more meant to activate them. I relate a lot to this approach, but I was curious if you can speak more about your relationship to these historical sources. For some it might seem like an irreverent relationship. Although I would argue it is the exact opposite, for in refusing to treat your sources as knowable systems whose fate has been sealed, it is extending them the respect of keeping them alive or maybe of bringing them back to life. Perhaps you can describe in your words what this relationship to sources may be?

Amit:

I resonate very much with your train of thought and attempt some more inquiry. Like we were discussing on the video call, why past and not future? Why are we not interested in the future, say science-fiction, but only the past? (Though lately, I have started writing a few science-fiction stories for children). Nevertheless, I think it’s the duty of every artist who comes from a colonized country to get in touch with their instincts. The idea is not to interpret or celebrate the tradition but to use it to get in touch with our reflexes, the inner layers of our own minds which are made of all this. It’s very important to state that it’s not and should not be a regressive project. Of course, not everything old is necessarily good or bad. They had different ways of organizing their societies, and every kind of organization will give rise to different kinds of genius. Holding on to the necessary human urge for harmony and beauty alone, we need to remember that what could be achieved in certain times can’t be achieved in another structure. Not everyone can engage with this project; it’s tiring and full of potholes. One needs to be like a mythical swan that separates milk from water. One needs to have a very balanced and calm mind to deal with this.

And as you say, we cannot assume or force a complete entry into any system of thought or material culture through its fragments alone, no matter how carefully gleaned. As an extension, I feel even the present is available to us only in fragments. Maybe it is this layered, fragmented coexistence of several times and spaces within us that intrigues me. In a present moment of heightened attention, they yield a rich glimmer or overview of human perception that defies subjective assumptions. Recently, I was looking at a work by Japanese artist Aki Inomata, who has experimented with a similar idea at the evolutionary/biological level. Like her bagworms that glean bits and pieces from modern clothing to make their primordial cocoon, or the octopus that immediately finds home in a 3D printed fossil shell, maybe subconscious layers of cultural memory get activated in unexpected ways within us when we access some poignant remnants from humanity’s history. It is indeed delicate and double-edged, a fine balance between organic reflex and consciousness.

Iman:

I am curious to hear you speak more about your attraction to different traditions of organizing the world. On my end, I was actually not so interested in history per se. In fact growing up in Egypt where many artists there and in the region were working with the idea of history, I was very resistant to it. Even when I crossed paths with it I would keep referring to my work in terms of the structures it was dealing with like saying for example, “I am working on existing monuments and not the history they claim to record,” and it was not until eight or nine years ago that this changed. I don’t have a clear reason why but part of me feels the 2011 uprising was somehow responsible. Perhaps it was due to the feelings it gave rise to of how the systems under which one is operating are nothing like what one thought them to be and that they need to be investigated from their very origins; that, with our failed systems, it was not just a matter of corrupt application but that the entire model was defunct. I am curious if your attraction to different traditions is also based on a search for different systems of understanding, organizing, and acting in the world? I should also maybe revise my use of the term “past,” because I liked very much how you refer to these traditions in terms of a coexistence of different times and spaces. That is actually more attuned to what I meant to say, for they are not really in the past at all, are they?

Amit:

It’s so fascinating to know about your journey. I have been looking at your work closely while we are talking and I am really impressed with your Book of Facts: A Proposition (2018). In it too I find this carefully composed coexistence of the past and present, an invitation to imagine a scenario through fragments of information that are too much and too little, too profound and too trivial at the same.

For me, it is actually a very challenging contrast to work out—the contrast between a complicated civilizational grand narrative spanning continents and millennia, and personal histories spanning a few landmark incidents that have shaped and shaken us as individuals and communities. I felt it very keenly while studying the art and life of Jangarh Singh Shyam (1962-2001), a modern painter who hailed from a remote tribal village in central India. It was never concluded whether he was a tribal artist or a modern artist who happened to be tribal, but he was successfully negotiating his place in the “mainstream” world. At the peak of a spectacular career after his migration to the city, he suddenly committed suicide in a Japanese museum. I could not contend with his journey as merely personal history; the explanation I sought could only be found in grander themes of the history of our country and its history of art, education, and fountainhead concepts, in the recent and distant past. I very much relate to that artist’s journey, as what is an organic subjective tendency for me has always been looked at as “alternative” in some way—say experimental, or parallel. It always made me wonder about our givens, be it through formal education or news or history. What we perceive naturally is mostly expected to be phrased in a set way to be valid in a given context, however specialized the context may be. Somehow I tend to remain uneducated about those set ways, and often learn of them only after I have said or done something.

In that sense, though I would be hesitant to say that I am looking for an alternative system, I can probably say I end up finding them [alternative systems] everywhere, even within myself. Like Lao Tzu said, “A good traveler has no fixed plans and is not intent on arriving.”

[Read parts one through six here: I, II, III, IV, V, VI]

-

For more information, contact program@e-flux.com