The Films of Amit Dutta: Week #2

Nainsukh

Amit Dutta

2010

82 Minutes

Artist Cinemas

Date

Repeating April 18–19

Nainsukh delves into the mid-eighteenth century, where an extraordinary master painter from the Himalayan foothills of Guler sets out on a journey to meet his patron in the small hill-state of Jasrota. He finds his match in the eccentric employ of Balwant Singh, the only remaining testimony of which are the painter’s intimately observant portraits of his employer.

Nainsukh is the second installment of The Films of Amit Dutta, a selection of films programmed by Iman Issa as the tenth cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film.

The Films of Amit Dutta runs in six weekly episodes from March 7 through April 18, 2022, and features six films by Amit Dutta accompanied by a conversation in six parts between Amit Dutta and Iman Issa, published in text form. A new film and part of the conversation are released every Monday. Each film streams for the duration of one week.

Amit Dutta in Conversation with Iman Issa

Part II

[Read parts one through six here: I, II, III, IV, V, VI]

Iman:

You have described your films as organized like a puzzle. I was intrigued when I read this. Being myself someone whose work is sometimes referred to as cryptic—which is far from my own perceptions of or intentions for the work—I related very much to the idea of a work being a puzzle, which is different from an opaque work or one that tries to hide itself. For in a puzzle, a viewer who invests the time and energy of following the logic of the work may be able to place all the pieces so that they fit perfectly together. Also, a puzzle is strictly about the material at hand and not its maker and their psyche. In a puzzle, a viewer doesn’t need to know much about who the maker is, one needs to only view attentively the material at hand. Can you expand a bit on what you meant by describing your work as a puzzle and why that might be a generative format?

Amit:

Puzzles playfully challenge our comprehending habits. To solve them we have to recalibrate our thinking pattern. Similarly, a film or even any art form is working with the viewer’s attention. In films, there is sound, composition or the arrangement of the elements within a frame, then there is movement—elements coming in and going out constantly, narrative, the movement of the actors, of the camera. All these elements are like the threads in the loom of our consciousness; and we play with them, creating harmonious patterns that might reveal our true nature. That is the primary function of any art form. Those patterns create challenges in the form of puzzles for the viewer. Sometimes through these puzzles the viewers find themselves. You know in India, there is a tradition of puzzle-making where there is no solution, the puzzle itself is the destiny. Let me take this opportunity to let you know how deeply I admire your work. I did not find your work opaque. I found it transcendental, deeply moving and sensitive. The object and text together create a fascinating puzzle which took me on a wonderful journey of ideas and epiphanies.

Iman:

When you say a puzzle with no solution, you mean one where the pieces do not end up all fitting or one that doesn’t provide a coherent picture in the end? Even though your films don’t leave one with a single idea that can be summarized using words, they still give the feeling that they are based on a rigorous logic. I rewatched Nainsukh (2010) yesterday and I realized that attention on my part to every element from the slightest change in sound, to an actor’s subtle movement, to the camera pans, to the parts you choose to show from the paintings, is essential to the intake of a sequence. Nothing was just happening, nothing could be ignored, every element appeared to be in the service of a ”meaning” or maybe you would say an “idea”?

Amit:

When you make a film intensely, the more meticulous you are, the more you become aware of the fact that you are in control of very limited elements. Suppose, I take a shot and I direct camera, costume, actors, sound, movement of the camera and the actor; at the same time I am aware of so many elements I am not in control of: the sudden shift of light halfway through the shot, a random bird fluttering in the background, an involuntary action by the actor, a small accident with the camera—various such things keep adding on at every step until you see a different film. A shadow film emerges in front of your eyes and it’s so mysterious that you marvel at the complexity of the medium. This is a puzzle, which will never have a solution; you sense the elements and a sense of harmony in these pieces, but it’s beyond you to solve it. As a filmmaker I recognize this complexity and the puzzle, and I leave it for the viewer who may find multiple ideas and interpretations. And this is precisely what has happened with my films. I have come across multiple interpretations and really appreciated them.

Iman:

In your book Many Questions to Myself (2018), you write that in Nainsukh “the missing architecture was built with sound.” You also make clear your distaste for surround sound, writing: “Let the sound come from the two dimensional screen.” Might you speak a bit about your relationship to and use of sound? To me it is one of the most poignant and yet baffling part of your films. The sound is not exactly diegetic but it is not extra-diegetic either for it seems so ingrained to the images. I can’t think of other examples where the sound is so utterly separate from and simultaneously inextricable from the images. The effect is very powerful, driving one to constantly rethink the relationship between what is heard and seen. Moreover, the sound itself seems to be a main protagonist, sometimes literally showing an action that is not seen, or animating what is usually inanimate such as when a statue of a swan starts trumpeting or an image of a tiger starts roaring. There also seems to be a collection of sounds that make repeated appearances in your films such as door bells and phones ringing, water drops, footsteps, metronomes or clocks, all divorced from any direct narrative consequences following from them and yet are clearly essential to the unfolding of each sequence.

Amit:

Sound helps me (and hopefully the viewer) inhabit a different space and time. There is a wonderful book called Yog Vashishth. The stories in it are so mysterious that once you read it your sense of space and time shrinks and expands in an astonishing way. It was so popular in medieval times that Mughal emperors translated it into Persian many times and even commissioned miniature paintings based on the stories. Some of Borges’ stories remind me of this book. I use sound to tap into that space which is beyond words and visuals. Sound as a separate universe which collides with the visual one. It helps me in exploring a universe which is beyond even the limits of the subconscious.

I find it most inspiring and uplifting when pleasure is devoid of desire. This is the highest form of aesthetic experience. By making sure that the sound is coming from the source and there is no superficial desire to mimic reality, we come close to that superior aesthetic experience.

Iman:

You have also mentioned how the digital format and using animation have allowed you to do things that would not have been possible otherwise; that they allow you to work on a very intimate scale, where you yourself are doing most of the work. I certainly relate to this idea of a small production where one is collaborating with a handful of others at the maximum, but it is very unusual in film. And yet you give a sense of immense possibilities with such limited means in your films. Can you speak more about the process of making films and the role of the technologies you employ in shaping them?

Amit:

Actually the main thrill in doing cinema is to make the highest quality possible with the lowest means. This is what is more exciting about this process. Like most of my films are low budget, some are even no-budget. It gives me deep satisfaction. When I write something that is complex and needs a lot of money to realize, I ask myself, can I still do it without any money? That is the question. Animation helps in tackling very complex and expensive ideas. I realized its scope thanks to my wife and partner Ayswarya.

I have often thought about the two modes of cinema production, those of construction and recognition, and have always gravitated towards the latter. I like to construct more at the level of ideas, or on the editing table, or through technology. While shooting, I prefer recognition, unless an intimate work of art can be produced instead of expensive sets that need to be discarded. That kind of make-believe has never attracted me, as it feels superfluous or second-hand to literature, for instance.

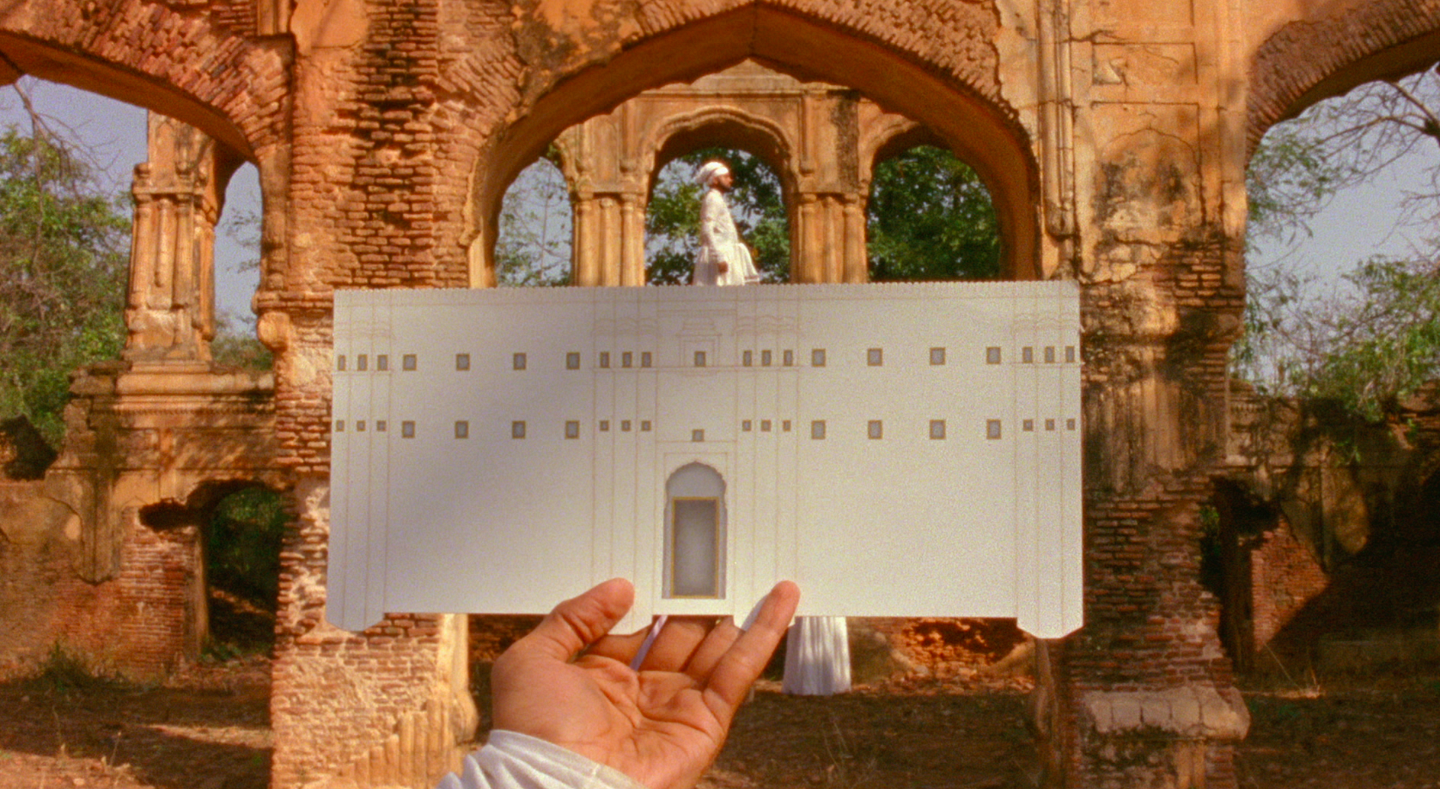

There are many levels to recognition. But let me take the filmed spaces as an example. In Nainsukh, I chose to keep the ruined palace grounds as a “recognized space” and did not want to reconstruct the setting physically but through sound design. So even though the architecture has no roof on the screen, deep echoes construct large domed halls in the experience of that visual. After a while one tends to forget that the setting is actually incomplete.

[Read parts one through six here: I, II, III, IV, V, VI]

-

For more information, contact program@e-flux.com.