Artist Cinemas presents

Shungu: The Resilience of a People

Saki Mafundikwa

2009

54 Minutes

Artist Cinemas

Week #5

Date

July 12–18, 2021

Join us on e-flux Video & Film for an online screening of Saki Mafundikwa’s Shungu: The Resilience of a People (2009), streaming from Monday, July 12 through Sunday, July 18, 2021.

In 2000, the Zimbabwean economy collapsed as a consequence of two negative forces, one external and the other internal. The external: neoliberal globalization; the internal, party corruption. Shungu: The Resilience of a People starkly surveys the ruins of this twin catastrophe.

It is presented alongside an essay by Charles Mudede written in conversation with the filmmaker.

Shungu: The Resilience of a People is the fifth installment of Planet C, a program of films and essays convened by Charles Mudede, and comprising the seventh cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film.

Planet C will run from June 14 through July 26, 2021, with a new film and essay released each week.

The Colliding Worlds of Shungu

Charles Mudede

Why does the famous Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli begin the penultimate chapter, “For Nature It Is a Problem Already Solved,” of his new and short book about the formative years of quantum theory, Helgoland: Making Sense of the Quantum Revolution, with a sudden detour to an area of science that has, on the face of it, nothing to do with the leading subject of his book (Werner Hesienberg), or his celebrated work in loop quantum gravity, or even the micro-constituents that make up the basal society of reality, neurobiology? That question has an answer that this piece of writing will not provide because what matters at present is not Rovelli’s deep thoughts about this field of science and its possible connections with his own, but his simple description of an emerging concept of the brain and how it functions.

Rovelli writes:

“One of the most fascinating recent developments in neuroscience concerns the functioning of our visual system… It would seem natural to think that receptors detect the light that reaches the retinas of our eyes and transform it into signals that race to the interior of the brain, where groups of neurons elaborate the information in ever more complex ways, until they interpret it and identify the objects in question.

It turns out, however, that the brain does not work like this at all. It functions, in fact, in an opposite way. Many, if not most, of the signals do not travel from the eyes to the brain; they go the other way, from the brain to the eyes.”

This relatively new area of research, known in neuroscience as “predictive processing,” was detailed, with impressive thoroughness and compactness, by the British philosopher Andy Clark in a 2012 paper, “Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science.” And the key concept of this research is, as Rovelli explained, the way the brain decodes or computes experience. It turns out that Kantian transcendentalism is far from the mark; but so too is the common conception of the relationship between the objective and the subjective. The brain does not generate anything like a mirror of reality, but instead has a “generative model” of reality that makes predictions about what each moment might be about. God may not play dice, but the brain does.

And so, what you have going out of this kind of society of cells—the brain, which Clark calls a “prediction machine”—is an idea of the world or the situation that surrounds one; and what’s coming in is sensory (visual, tactile, sonic) information that a “cascade of cortical processing” checks against the brain’s predictions. Put another way, the brain, in this “top-down” orientation, is scanning inputs for errors. The brain wants no surprises.

So far, so good.

Now, you might be wondering, why bring all of this predictive brain stuff up in a piece about Saki Mafundika’s 2009 documentary Shungu, which in Shona, the main black African language in Zimbabwe, means “will,” as in “the will to survive” or the “will to power”? Surprisingly, it has everything to do with it, everything to do with the society of individuals Mafundika investigates with some sound equipment and a digital camera.

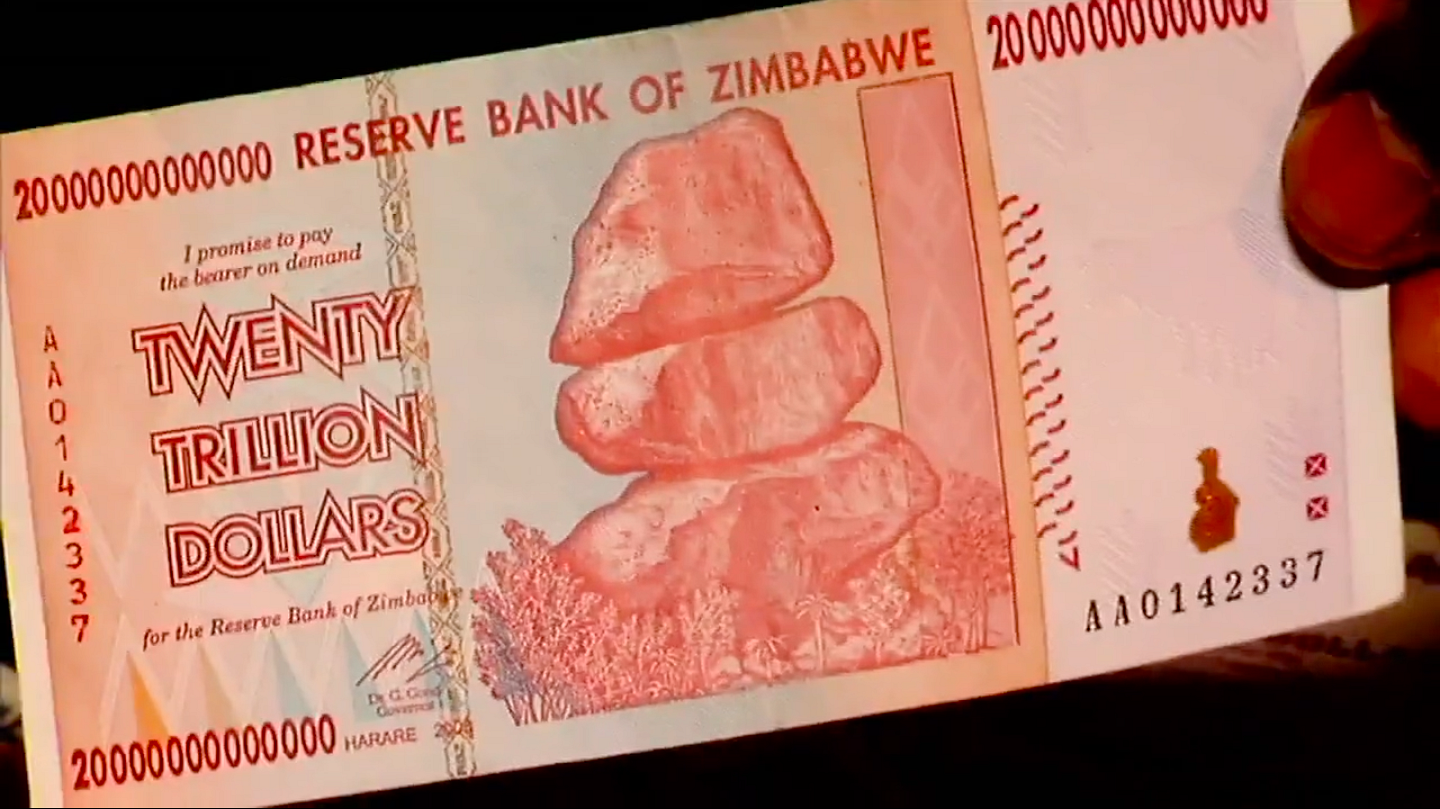

Here (in this film) is Zimbabwe nearly thirty years after independence from a century of white rule. The country is a total mess at this point. Democracy, which never really left its point of birth—the 1980 election that led to the formation of the new state—is still stuck in 1980. The economic crisis, which expanded when the country implemented, in the early 1990s, the Washington Consensus’s structural adjustment program of small government, limited state intervention, floating flows of borderless hot money, and the abandonment of classical development policies, such as import substitution or infant industry formation, has become seemingly permanent. There are shortages of all kinds. The Zimbabwean currency is worthless. Robert Mugabe, the country’s first president, has it in mind to stay in power until the Second Coming. And when you think things couldn’t get any worse, they somehow do. One of Mafundika’s subjects is a doctor working in a health system that crashed long ago.

Saki Mufundikwa writes:

“Shungu, my first feature documentary is pure emotion, it is my response to the situation in my country. It is also fraught with frustration at a situation that most people feel did not have to go the way it has. Zimbabwe is a young country which attained its independence thirty years ago offering a lot of promise for economic growth and stability. It is a favorite pastime of most Zimbabweans to engage in heated arguments over where we went wrong and how best we can rise out of the misery that is most people’s lives today…”

The documentary, however, does not offer an answer to what went wrong. But it does present an economic reality that’s better understood if the functions of the predictive brain described by Andy Clark are appreciated. “Our basic means of representing the world, and prediction-error minimization” is, according to Clark, “the driving force behind learning, action-selection, recognition, and inference.” But here is the catch. This represented world is in reality not all natural in the nature/culture sense. A considerable part of it is constructed not just by local cultures and traditions but by a relatively new economic order with a totalizing logic. We call this universal culture capitalism.

Those inside of this world-within-a-world (a second—if not third—nature) do not hunt, they shop. They do not work to consume directly but for wages, which provide the income to shop for goods that are produced by other wage workers. In our times, the long-evolved predictive brain is most likely simulating a city rather than a forest.

Clark is not ignorant of this fact. He writes:

“The basic organizing principles highlighted by action-oriented predictive processing make us superbly sensitive to the structure and statistics of the training environment. But our human training environments are now so thoroughly artificial, and our explicit forms of reasoning so deeply infected by various forms of external symbolic scaffolding, that understanding distinctively human cognition demands a multiply hybrid approach.”

The thing that one must keep in mind while watching Shungu is it presents, at every moment, a black African society that over one hundred years ago was thoroughly transformed by capitalism. The subjects of the documentary are consumers and wage earners. They and the generation before them have lived in no other social system than the one that’s dominated by exchange value and property rights. As for the director, Mafundikwa, his background as a graphic designer meant he spent a considerable part of his career in marketing in Manhattan and Harare. In fact, one of his most famous designs in Zimbabwe is for a mass-marketed album by the pop icon Thomas Mapfumo. The album identified one of the reasons for “what went wrong” in Zimbabwe as corruption.

The question one must ask at this point, then, is: What happens when an economic system that has directed and shaped expectations for generations, completely collapses? What do the consumers of commodities do when “the realm of social action and multiagent coordination” is under the kind of stress that continually frustrates predictions?

Capitalism is a system that continually promises consumers a reduction of “errors in predicting;” the brain is a surprise-reducing machine. These worlds have collided in Shungu.

For more information, contact program [at] e-flux.com.