https://theartstudentsleague.org/

Instagram / Twitter / Facebook

Earlier this month, the College Art Association held its 113th annual conference in New York. From February 12–15, art historians, educators, curators, publishers, artists, designers, and other professionals in the arts gathered to share their scholarship and absorb that of their peers. As part of the session “The Art Students League: 150 Years of ‘American’ Art,” Daniel Belasco, an art historian and the Executive Director of the Al Held Foundation, provided critical new insight into the Art Student League’s role in shaping American Social Realism. Belasco’s research focuses on several teachers and students at the League—in addition to artists and activists in its larger orbit—who influenced the movement’s turn towards depicting themes of racial injustice, nearly a decade prior to the dawn of the Civil Rights movement. His presentation has been adapted into the following essay.

This paper explores the last gasp, as it were, of social realist painting in New York in the late 1940s and ’50s, a period marked by the political and economic pressures of anti-communist purges and a stylistic shift to Abstract Expressionism. Social Realism and its various iterations—American Scene, Regionalism, and realism—dominated American art in the 1930s and early ’40s; by the end of that decade, it was steadily pushed to the margins as it lost its audience, government funding, and critical attention. However, a small group of artists remained committed, bolstered by personal conviction, political activism, and the support of community institutions such as the American Contemporary Art Gallery, the Jefferson School of Social Science, and the Art Students League. Harry Sternberg, a longtime instructor at the League, exemplified in many ways the committed, socially conscious artist through his art, teaching, writing, and advocacy. His impressive list of students includes Isabel Bishop, Minna Citron, Karl Schrag, and Ed Clark.

I am interested not in the vanguard period of Social Realism of the 1930s, but its embattled later years, when its core imagery and political orientation shifted from an international brotherhood celebrating the worker and everyman to the domestic political fight for racial equality in the United States.1 This change opened space for Black artists such as Sternberg students Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett, as well as Roy DeCarava and Jacob Lawrence, to gain authority and prominence for their social art. The shift also compelled more white artists to confront their own position and create art about the persecution of African Americans. As a case study, I will localize this phenomenon among a cadre of artists who, faced with federal censorship and repression, carried the torch for Social Realism. They saw art as a weapon in the political and cultural battle over hearts and minds in postwar America.

I backed into this topic through a dead end. As the executive director of the Al Held Foundation, I have followed every last thread of Held’s oral histories and primary texts to fill out his artistic development as completely as possible. In his oral history with the Archives of American Art, Held reflects on his days at the Art Students League on the late 1940s and early ’50s. He went to the League starry-eyed, galvanized by Mexican muralism and enthralled with “idealism of [art] serving the people.”2 A red diaper baby and a late bloomer, Held fell into the American Folksay Group of American Youth for Democracy, an organization devoted to left-wing folk culture and political activism, after a two-year stint in the Navy. His predisposition to communist youth culture pulled him to Greenwich Village, where he participated in square dances, May Day parades, and the 1948 campaign for progressive presidential candidate Henry Wallace. Arriving at the League in May of 1949, he aspired to paint huge murals, but first felt the need to learn the craft of figurative painting. Taking advantage of the open educational structure of the League, he studied anatomy and drawing with Robert Beverly Hale and painting with Jon Corbino and Morris Kantor, among others. The vibrant discourse in the cafeteria became his graduate seminar in contemporary art.

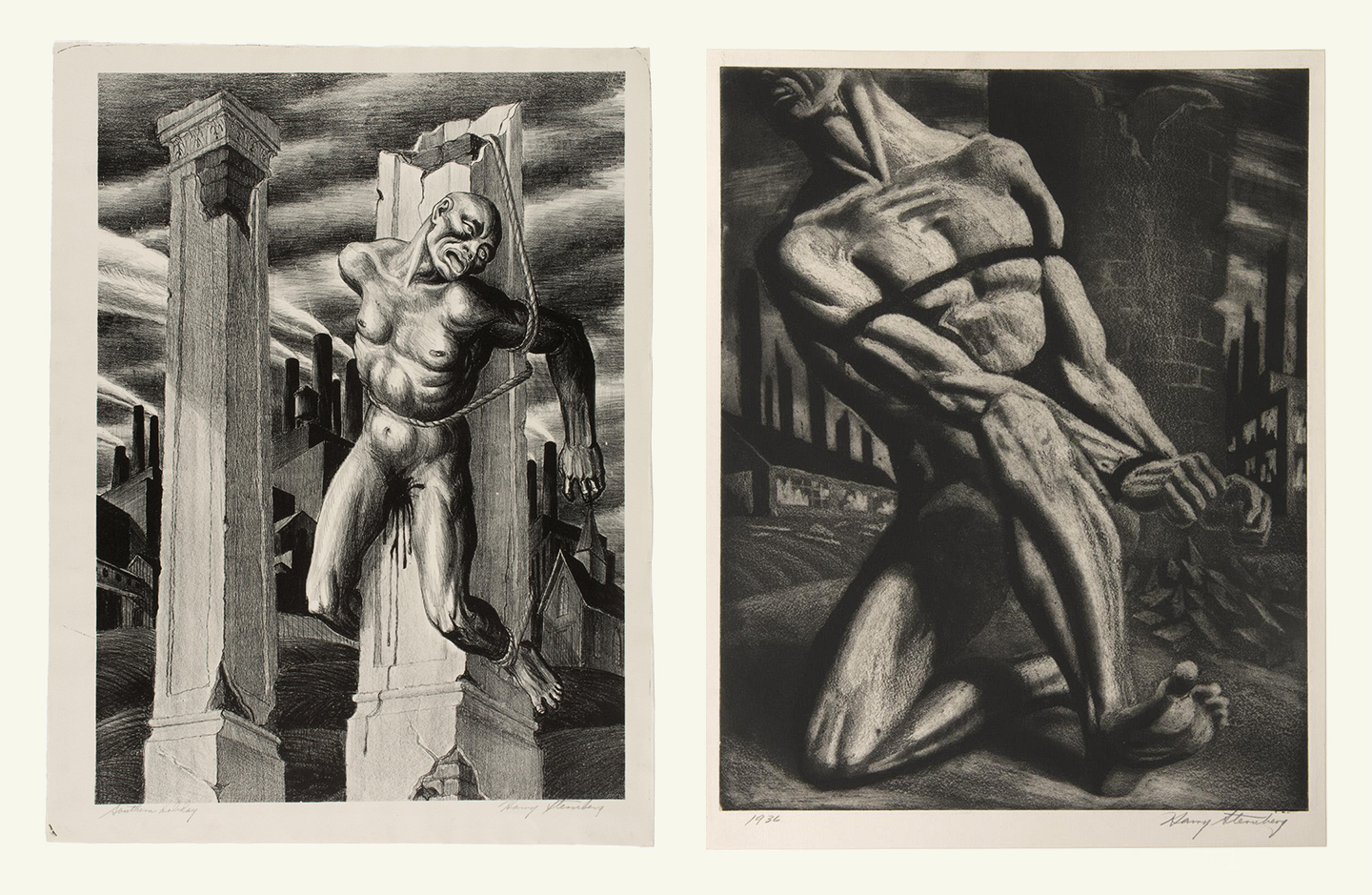

Sternberg made the biggest impact on Held. Already aligned with the values of Social Realism, Held took three courses with the left-wing artist in graphics, painting, and composition. With Sternberg, Held studied the lexicon of protest images, such as the horrors of lynching and capitalism in his lithograph Southern Holiday (1935) and the struggle for liberation in his aquatint Bound Man (Enough) (1947). The League exposed Held to new stylistic influences to help him learn not only what he would paint, but how. He became especially enthralled with the formal innovation in the work of David Alfaro Siqueiros, who torqued and twisted volumes with intense foreshortening and what muralist Arnold Belkin termed “dynamic perspective.”3 Many League students travelled to Mexico to learn from Siqueiros and assist in his projects.

Notably, Held also admired the work of Charles White, “because of his big boldness.”4 Held recalled that White was “there” at the League in some capacity. This bit of information intrigued me, as White was an unexpected influence on Held, who is best known as a pioneer of hard-edge abstraction in the 1960s. But in considering White’s dramatic handling of scale, modelling, and perspective in prints such as Trenton Six and The Ingram Case, both 1949, I could identify his influence on Held’s thinking, from his earliest sketchbook through his late abstract painting. The massive forms in White’s drawing amplify the active structures in the prints of Sternberg, who White called “by far the most stimulating and understanding instructor I have ever worked with.”5 White’s work was widespread in New York in the late ’40s and ’50s and Held imbibed its striking combination of spatial aesthetics and passionate social commentary.

Charles White, Trenton Six, 1949. Ink and graphite on paperboard, 21 15/16 x 29 7/8 inches. Courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. © The Charles White Archives.

It turns out, however, that despite Held’s reminiscence, White never taught at the League.6 It is plausible that he substituted in Sternberg’s classes from time to time. Or that he occasionally passed through to shoot the breeze. Maybe Held encountered White’s art on visits to an important ACA Gallery show in February of 1950. Or on the cover of Masses & Mainstream in January and February of 1951. Perhaps Held conflated the presence of White with that of Charles Alston, the League’s first Black instructor, hired in 1950 after pressure by a student group. Held’s acknowledgement of White is perhaps more constructive of aesthetic history than disparate facts, for it coheres several critical contexts—Social Realist style, postwar American politics, and the Art Students League—in one place and time. The fantasy of Charles White teaching at the League prompts this investigation of anti-racist activities in the late 1940s and early ’50s by and around Harry Sternberg fostered by League connections.

Never a strict naturalistic painter, Sternberg himself abandoned Social Realism in the late 1940s, choosing instead to create figurative prints, drawings, and paintings that represent modern anxieties and the incursion of television into the American psyche. Born in New York in 1904, Sternberg had been a leading light in the protest art movement, creating political imagery while embracing new techniques to disseminate prints more widely to the working class. With series on coal miners and the steel industry, supported by a Guggenheim Foundation grant in 1936, Sternberg became a leading voice in arguing for the persuasive power of art to protest American injustice.

America’s entrance into World War II complicated the purity of critical voices. The righteous fight against Hitler and Mussolini highlighted the American fascism of Jim Crow, augmenting sympathy for the Stalinist USSR for standing up to Nazi Germany. Sternberg seems to have somewhat lost his way, producing rather tepid prints like Man and War (1941) and Woman and War (1942). Postwar, Sternberg developed a surrealistic painting series titled Recent Paintings on Man’s Insecurities, exhibited in a solo show at ACA Gallery in late 1947. One canvas titled Color of Skin (1947) depicts a dark-skinned man cast out from a smirking group of light-skinned men and women in the protective cocoon of society into a harsh and isolated wilderness.7 The project seemed to emerge from a shift in his philosophy from class warfare to psychological struggle. As Sternberg explained in a statement in The League Quarterly, art cannot be taught because teachers, as human beings, are as confused as their students.8 The best a teacher could do, he wrote, was to help the student clear away inhibition, prejudice, and fear.

This subjective turn in Sternberg’s art and teaching resonated with the moment, as a younger generation recognized that new voices of social commentary, protest, and progressivism were needed to confront the rising tide of what was then called white chauvinism. His students continued to advance messages of solidarity and dignity through a commitment to figuration in response to “the realization that Southern racism was central to the conservative turn of U.S. politics in the 1940s.”9 Some of them came together to organize a collective to promote togetherness, purpose, and the power of prints, rather than murals, to confront the issues of the day.

In the spring of 1948, a group of artists, many of them former League students, established the Workshop of Graphic Art.10 Modeled in part on the left-wing Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) in Mexico City, the membership-based Workshop ran courses and sought business by designing and printing pamphlets, posters, leaflets, and greeting cards for groups such as the Artist League of America and the American Artists’ Congress. They urged artists to get involved in the fight against the repressive Mundt-Nixon Bill, a proposed law that would have required all members of the Communist Party to register with the Department of Justice. Jacob Landau, the Workshop’s founding director, studied at the League, and Charles Keller, the Workshop’s president, had worked as an assistant on Sternberg’s Federal Art Project mural in a Chicago post office. Sternberg and Keller also shared a studio on East 14th Street, several blocks from the location of the Workshop. In addition to their work for hire, the Workshop self-published two loose-leaf print portfolios, likely inspired by the TGP’s loose-leaf portfolio Estampas de la revolución Mexicana (Prints of the Mexican Revolution, 1947), which exemplified Sternberg’s teachings that artists should produce low-cost, easily accessible, and socially conscious work to reach large audiences.

A poster made by Taller de Grafica Popular members Ignacio Aguirre, Everardo Ramírez, and Alfredo Zalce, c. 1940–42. Linocut, 26 3/8 x 35 7/8 inches. Counter-clockwise, from top left: Alfredo Zalce, Eight-Hour Workday; Agnacio Aguirre, Seven Days’ Pay for Six Days’ Work; Aguirre, Annual Vacations; Zalce, Study Center; Everardo Ramírez, Health Care. Reproduced in Mexico and Modern Printmaking: A Revolution in the Graphic Arts, 1920 to 1950 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2006), p. 218, fig. 269.

The Workshop first published Yes, the People! in December 1948, sold for a dollar a copy.11 The title derived from Carl Sandburg’s epic book-length prose-poem The People, Yes (1936), which celebrates the people of the world as a heterogeneous collective united by their humanity.12 Leonard Baskin articulated a message of solidarity in the portfolio’s foreword: “A group of young artists have come to realize that if their art is to survive as healthy and vital work, it must establish honestly and forthrightly, intimate and strong ties with the working people of America.”13 Landau, director of the Workshop, contributed the woodcut of the raised fist in resistance, bearing their weapons of brushes and burin. Seven artists contributed a dozen prints. Four of them studied with Sternberg at the League.

Celebrated woodcut artist Irving Amen’s Folk-singer and Flight, both included in the portfolio and dated, with the rest of the prints, to 1948, span the two primary emotional valences of classic Social Realist art: in the former, a heroization of the people’s art, with the bright sun shining on the buoyant singer; in the latter, sympathy with the dispossessed and downtrodden, as in the old refugee couple who are perhaps victims of German aggression. Jewish themes became one of Amen’s primary subjects over the course of his career. Charles White also contributed two lithographs based on his drawings, presumably executed while in Mexico in 1946 with his then-wife Elizabeth Catlett. Mexican Woman and Mexican Boy cast a sympathetic eye on two barefoot individuals, decontextualized from any specific environment. Their somewhat exaggerated facial features and physical proportions, especially in the female figure, typify White’s expressive use of monumentalism. Two other prints by lesser-known artists who studied etching with Sternberg document rural people far from New York City. Phyllis Skolnick produced the woodcut Coal Miner’s Family, of a family huddling around a small child in bed, perhaps ill and in need of comfort. Eugene Karlin’s lithograph Southern Negro Girl, the only specific image of a Black person in the portfolio, is an unusual rendering with elongated neck, sort of a Mannerist Madonna of the farm. The portfolio’s success encouraged the Workshop to produce a second, this time fully devoted to African American freedom and history.

Negro: U.S.A.: A Graphic History of the Negro People in America appeared in February 1949 in conjunction with what was then National Negro History Week. More ambitious in scope and size than Yes, the People, Negro: U.S.A. contained 26 prints contributed by fifteen artists and had a striking image by Charles White on the cover.14 For Keller, the portfolio exemplified the Workshop’s mission to create “an art which expresses the living content of our democratic striving for creative fulfillment, peace and abundance.”15 The foreword by Herbert Aptheker pinpointed the purpose of the portfolio to envision “the movement and grandeur of Negro history.” Most of the prints depict scenes from American history, some concerning historical figures like Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, and Crispus Attucks. Keller contributed The Artisan and the Governor of Virginia, rendered in a cartoonish line that recapitulates caricatures of the physical power of Black men and the insipid decadence of the Southern gentry. There were also scenes of struggle and solidarity, of union strikes, protests, and individual commitment. White artists were the ones to portray scenes of racial violence and exploitation, such as Klan terror, a slave auction, and segregated housing in the North. Notably, the three Black artists with work in the portfolio eschewed overt representations of pain and instead expressed communal resistance, as in Charles White’s Our War, Roy DeCarava’s “Together, We’ll Win …”, and Jacob Lawrence’s Underground Railroad: Fording a Stream. Art here, according to Aptheker, “is itself a weapon in the battle for a free America.”16

Left: Cover of Yes, the People!. Portfolio by The Workshop of Graphic Art, 1948. Prints on paper, 14 x 9 inches each. Cover by Jacob Landau and Louis Glassman. Right: Cover of Negro U.S.A. Portfolio by The Workshop of Graphic Art, 1949. Prints on paper, 14 x 9 inches each. Cover by Charles White. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Though largely absent from mainstream colleges, courses on Black history and art were a staple of Marxists institutions like the Jefferson School, where Aptheker taught. There was a large cultural department, and artists Gwendolyn Bennett, Philip Evergood, Norman Lewis, Charles White, and others led drawing and painting workshops in the late 1940s and early ’50s.17 By then, heroic images of workers and the proletariat—and even the very word “people”—had become coded as communist subversion, and risked exposure to congressional hearings. Similarly, as the lofty promises of equal rights made to Black veterans faced a harsh postwar reaction, calls for racial solidarity commonly graced the covers of Jefferson School course catalogues. Perhaps it was not a coincidence that around the time of Negro: U.S.A., a group of students at the League organized the Artists Committee for Cultural Advancement to push for the hiring of the first Black instructor at the Art Students League.18 The League denied harboring racial prejudice, but realized it was on the wrong side of history.19 After Alston’s appointment, Sternberg praised the integration of the faculty as “another sign of increasingly democratic breadth of the League.”20

This emerging race consciousness, both within the League and among its politically active alumni, contextualizes Al Held’s early work. Though he discarded all paintings from this period, we do have a few descriptions of his imagery. One canvas portrayed a monstrous man “astride two buildings, one was a church and one was a bank. He had two outstretched hands and from each finger of the outstretched hand, hung a black man, lynched.”21 The message was clear: art held the capacity to challenge the twin evils of capitalism and religion that fueled white supremacy in America. For Held, the League, and other leftist institutions, the certainty of this position and its visual expression through Social Realism was not to persist much longer, however. McCarthyism and FBI pressure devastated the concept of the people’s art, forcing the Workshop of Graphic Art to close in 1951.22 Sternberg remained at the League until 1966, but the conversation had moved on from the collective responsibility of artists. This may have reflected a shift within the League itself from the social to the individual, from the public to the private, aligned with a larger stylistic shift toward experimental abstract imagery with progressive content. But that’s another story.

See Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002; Mary Helen Washington, The Other Blacklist: The African American Literary and Cultural Left of the 1950s, New York: Columbia University Press, 2014; and Erin Park Cohn, “Art Fronts: Visual Culture and Race Politics in the Mid-Twentieth Century United States,” Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Pennsylvania, 2010.

Al Held, interview by Paul Cummings, November 19, 1975–January 8, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Arnold Belkin, “Letter from Mexico,” The League Quarterly, no. 1 (Spring 1950): vol. 22, 17.

Al Held, interview by Paul Cummings.

Esther Adler, “Charles White, Artist and Teacher,” in Charles White: A Retrospective, Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago; New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018, 142.

Stephanie Cassidy, Head of Research and Archives at the League, fulfilled numerous requests for information about League students, faculty, publications, and collections.

The painting is presently in the collection of the Art Students League.

Harry Sternberg, “Thoughts on Teaching,” The League Quarterly (Winter 1946), 6.

Hemingway, 260.

The certificate of incorporation, dated April 23, 1948, was signed by Kate Scherer, Edith Cohen, and Sally Bowman. Charles Keller Workshop of Graphic Art papers, box 1 folder 8, New York University Special Collections.

Other credits: typography by Hanna Heider and printing by Jane Filley.

Sandburg’s poem also contained the phrase “the family of man” which became the touchstone and title of the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark socially conscious photography show in 1955. Sandburg wrote the prologue for the catalogue.

Leonard Baskin, “Foreword,” in Yes, the People!, New York: The Workshop of Graphic Art, 1948.

The full list of contributors: Leonard Baskin, Roy DeCarava, Antonio Frasconi, Robert Gwathmey, Bud Handelsman, Charles Keller, Louise Krueger, Jacob Landau, Al Lass, Jacob Lawrence, Jerry Martin, Leona Pierce, Jim Schlecker, Edward Walsh, and Charles White.

Charles Keller, in Negro U.S.A., New York: The Workshop of Graphic Art, 1949.

Herbert Apthekar, “Foreword,” in Negro: U.S.A., The Workshop of Graphic Art, 1949.

The Jefferson School of Social Science papers, box 3, New York University Special Collections.

Werner and Yetta Groshans Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Copy shared by Stephanie Cassidy.

“Board of Control Clarifies Position on Negro Instructors,” Art Students League News no. 5 (March 1, 1950): 3, 2.

“An Oral History of the League,” The League no. 2 (Fall 1950): 22, 15.

Held, interview by Paul Cummings.

Hemingway, 195. In 1956, Khrushchev’s revelations of Stalin’s crimes against humanity dried up the remaining support for the Communist party in the U.S. That year, Masses & Mainstream, The Jefferson School, and the Civil Rights Congress, the party’s leading initiative for black rights, all closed.